Part One: Bagpipes in the Blata Region of Bohemia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Statistická Ročenka Plzeňského Kraje 2014

REGIONÁLNÍ STATISTIKY REGIONAL STATISTICS Ročník/Volume 2014 Kód publikace/Publication code: 330108-14 Plzeň, prosinec 2014 Plzeň, December 2014 Č. j./Ref. no.: 596/2014 - 7401 Statistická ročenka Plzeňského kraje 2014 Statistical Yearbook of the Plzeňský Region 2014 Zpracoval: Krajská správa Českého statistického úřadu v Plzni, oddělení informačních služeb a správy registrů Prepared by: Regional Office of the Czech Statistical Office in Plzeň, Information Services and Registers Administration Unit Vedoucí oddělení / Head of Unit Ing. Lenka Křížová Informační služby / Information Services: tel.: +420 377 612 108, e-mail: [email protected] Kontaktní zaměstnanec / Contact person: Ing. Zuzana Trnečková, e-mail: [email protected] Český statistický úřad, Plzeň Czech Statistical Office, Plzeň 2014 Zajímají Vás nejnovější údaje o inflaci, HDP, obyvatelstvu, průměrných mzdách a mnohé další? Najdete je na internetových stránkách ČSÚ: www.czso.cz Are you interested in the latest data on inflation, GDP, population, average wages and the like? If the answer is YES, do not hesitate to visit us at: www.czso.cz ISBN 978-80-250-2589-5 © Český statistický úřad, 2014 © Czech Statistical Office, 2014 PŘEDMLUVA Statistická ročenka Plzeňského kraje je klíčovou publikací krajské správy Českého statistického úřadu, přinášející z dostupných dat souborný statistický přehled ze všech odvětví národního hospodářství. Podobně jako v ostatních krajích vychází v nepřetržité řadě již počtrnácté, a to jak v tištěné, tak v elektronické verzi. Tyto tradiční obsahově sjednocené publikace navazují na celostátní statistickou ročenku, zpracovávanou v ústředí Českého statistického úřadu. Údaje o kraji jsou v zásadě publikovány za období 2011 až 2013, ve vybraných ukazatelích pak v delší časové řadě od roku 2000. -

Themenkatalog »Musik Verfolgter Und Exilierter Komponisten«

THEMENKATALOG »Musik verfolgter und exilierter Komponisten« 1. Alphabetisches Verzeichnis Babin, Victor Capriccio (1949) 12’30 3.3.3.3–4.3.3.1–timp–harp–strings 1908–1972 for orchestra Concerto No.2 (1956) 24’ 2(II=picc).2.2.2(II=dbn)–4.2.3.1–timp.perc(3)–strings for two pianos and orchestra Blech, Leo Das war ich 50’ 2S,A,T,Bar; 2(II=picc).2.corA.2.2–4.2.0.1–timp.perc–harp–strings 1871–1958 (That Was Me) (1902) Rural idyll in one act Libretto by Richard Batka after Johann Hutt (G) Strauß, Johann – Liebeswalzer 3’ 2(picc).1.2(bcl).1–3.2.0.0–timp.perc–harp–strings Blech, Leo / for coloratura soprano and orchestra Sandberg, Herbert Bloch, Ernest Concerto Symphonique (1947–48) 38’ 3(III=picc).2.corA.2.bcl.2.dbn–4.3.3.1–timp.perc(3):cyms/tam-t/BD/SD 1880–1959 for piano and orchestra –cel–strings String Quartet No.2 (1945) 35’ Suite Symphonique (1944) 20’ 3(III=picc).2.corA.2.bcl.2.dbn–4.3.3.1–timp.perc:cyms/BD–strings Violin Concerto (1937–38) 35’ 3(III=picc).2.corA.2.bcl.2.dbn–4.3.3.1–timp.perc(2):cyms/tgl/BD/SD– harp–cel–strings Braunfels, Walter 3 Chinesische Gesänge op.19 (1914) 16’ 3(III=picc).2(II=corA).3.2–4.2.3.1–timp.perc–harp–cel–strings; 1882–1954 for high voice and orchestra reduced orchestraion by Axel Langmann: 1(=picc).1(=corA).1.1– Text: from Hans Bethge’s »Chinese Flute« (G) 2.1.1.0–timp.perc(1)–cel(=harmonium)–strings(2.2.2.2.1) 3 Goethe-Lieder op.29 (1916/17) 10’ for voice and piano Text: (G) 2 Lieder nach Hans Carossa op.44 (1932) 4’ for voice and piano Text: (G) Cello Concerto op.49 (c1933) 25’ 2.2(II=corA).2.2–4.2.0.0–timp–strings -

Prezentace Aplikace Powerpoint

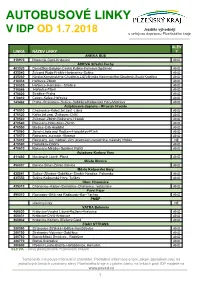

AUTOBUSOVÉ LINKY Jezděte výhodněji V IDP OD 1.7.2018 s veřejnou dopravou Plzeňského kraje SLEV LINKA NÁZEV LINKY Y ANEXIA BUS 310970 Rakovník-Čistá-Kralovice ANO ARRIVA Střední Čechy 403020 Domažlice-Babylon-Česká Kubice-Folmava-Spálenec ANO 435040 Železná Ruda-Prášily-Hartmanice-Sušice ANO 435060 Nýrsko,Komenského-Chudenín,Liščí-Nýrsko,Komenského-Chudenín,Svatá Kateřina ANO 210034 Hořovice-Zbiroh ANO 210035 Hořovice–Komárov– Strašice ANO 210046 Hořovice-Plzeň ANO 470800 Strašice–Praha ANO 470810 Cekov–Kařez–Hořovice ANO 143442 Praha–Strakonice–Sušice–Soběšice/Kašperské Hory-Modrava ANO Autobusová doprava - Miroslav Hrouda 470510 Cheznovice-Kařez,žel.zast.-Líšná ANO 470520 Kařez,žel.zast.-Zvíkovec-Chříč ANO 470530 Zvíkovec-Zbiroh-Rokycany-Hrádek ANO 470540 Rokycany-Holoubkov-Zbiroh ANO 470550 Mlečice-Čilá-Hradiště ANO 470560 Zbiroh-Lhota pod Radčem-Holoubkov-Plzeň ANO 470570 Rokycany,,aut.nádr.-Klabava ANO 475010 Rokycany, aut. nádraží-Jižní předměstí-nemocnice-městský hřbitov NE 470580 Holoubkov-Dobřív ANO 470610 Rokycany-Mirošov-Spálené Poříčí ANO Autobusy Karlovy Vary 411460 Mariánské Lázně–Planá ANO Město Blovice 450007 Blovice-Štítov-Ždírec-Blovice ANO Město Kašperské Hory 435541 Sušice–Žihobce–Soběšice–Strašín-Nezdice, Pohorsko ANO 435550 Sušice-Kašperské Hory, Tuškov ANO Obec Chanovice 435010 Chanovice–Kadov–Svéradice–Chanovice, restaurace ANO Pavel Pajer 490010 Rozvadov–Bělá nad Radbuzou–Bor–Tachov ANO PMDP všechny linky NE VATRA Bohemia 460830 Kralovice-Vysoká Libyně-Kožlany-Kralovice ANO 460831 Kralovice-Chříč-Kralovice ANO 460832 Kralovice-Kožlany-Břežany-Čistá ANO ČSAD STTRANS 380050 Strakonice-Střelské Hoštice-Horažďovice ANO 380150 Strakonice-Volenice–Soběšice ANO 380760 Blatná-Mladý Smolivec , Radošice ANO 380770 Blatná-Svéradice ANO 380800 Předmíř-Lnáře-Blatná–Horažďovice, Komušín ANO SLEVA – slevy poskytované Plzeňskám krajem Tento leták má pouze informační charakter. -

Text Částí Zákonů V Platném Znění S Vyznačením Navrhovaných Změn

Zákony pro lidi - Monitor změn (zdroj: https://apps.odok.cz/attachment/-/down/KORNA5FAPUZG) Text částí zákonů v platném znění s vyznačením navrhovaných změn Zákon č. 247/1995 Sb., o volbách do Parlamentu České republiky a o změně a doplnění některých dalších zákonů Příl.3 Seznam volebních obvodů pro volby do Senátu s uvedením jejich sídla Volební obvod č. 6 Sídlo: Louny celý okres Louny, celý okres Rakovník a část okresu Kladno, tvořená obcemi Drnek, Malíkovice, Jedomělice, Řisuty, Ledce, Smečno, Přelíc, Hrdlív Volební obvod č. 6 Sídlo: Louny celý okres Louny, celý okres Rakovník a část okresu Kladno, tvořená obcemi Drnek, Malíkovice, Jedomělice, Řisuty, Ledce, Smečno, Přelíc, Hrdlív, Hradečno Volební obvod č. 13 Sídlo: Tábor celý okres Tábor, východní část okresu Písek, ohraničená na západě obcemi Žďár, Tálín, Paseky, Kluky, Dolní Novosedly, Záhoří, Vrcovice, Vojníkov, Vráž, Ostrovec, Smetanova Lhota, Čimelice, Nerestce, Mirovice Volební obvod č. 13 Sídlo: Tábor celý okres Tábor, východní část okresu Písek, ohraničená na západě obcemi Žďár, Tálín, Paseky, Kluky, Dolní Novosedly, Záhoří, Vrcovice, Vojníkov, Vráž, Ostrovec, Smetanova Lhota, Čimelice, Nerestce, Mirovice, a jižní část okresu Benešov, tvořená obcemi Votice, Neustupov, Miličín, Mezno, Střezimíř, Jankov, Ratměřice, Zvěstov Volební obvod č. 16 Sídlo: Beroun část okresu Beroun, ohraničená na západě obcemi Hudlice, Svatá, Hředle, Točník, Žebrák, Tlustice, Hořovice, Podluhy, část okresu Praha-západ, ohraničená na severu obcemi Číčovice, Tuchoměřice, na jihu obcemi Řevnice, Dobřichovice, -

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart

Saturday, September 8 1979 Arts Guild Fair, Central Park, Northfield Overture to the Magic Flute (Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart) Finlandia (Jean Sibelius) London Suite (Eric Coates) Country Gardens (Percy Grainger) Berceuse and FInale- Firebird (Igor Stravinsky) Dance Rhythms (Wallingford Riegger) Simple Gifts (Aaron Copland) Hoedown (Aaron Copland) August 23, 1986 Carleton College Concert Hall Carneval Overture (Antonin Dvorak) Valse Triste (Jan Sibelius) Konzertstuck for Four Horns and Orchestra Wedding Day at Troldhaugen (Edvard Grieg) Highlights from Showboat (Jerome Kern/Oscar Hammerstein) Why Do I Love You? Can’t Help Lovin Dat Man You Are Love - soloist- Myrna Johnson The Moldau from Ma Vlast (Bedrich Smetana) American Salute (Morton Gould) August 28, 1986 Fairbault Junior High Auditorium- 7:30 pm Carneval Overture (Antonin Dvorak) Valse Triste (jan Sibelius) Konzertstuck for Four Horns and Orchestra Prelude to Act III of Lohengrin First Movement from Violin Concerto no. 3 in G, K216 (W.A. mozart) The Moldau from Ma Vlast (Bedrich Smetana) American Salute (Morton Gould) Saturday, May 14, 1994 United Methodist Church, Northfield- 2:30pm Northfield Cello Choir (Directed by Stephen Peckley): Pilgrim’s Chorus (Richard Wagner) Sarabande and Two Gavottes (J.S. Bach) Red Rose Rag (Traditional) Suite for Strings in Olden Style from Holberg’s Time, Op.40 (Edvard Grieg) Prelude: Allegro Vivace Sarabande: Andante Rigaudon: Allegro Con Brio Geraldine Casper- violin solo Paul Tarabek- viola solo Concerto in D Major for Cello and Orchestra (Josef Haydn) -

Compact Discs by 20Th Century Composers Recent Releases - Spring 2020

Compact Discs by 20th Century Composers Recent Releases - Spring 2020 Compact Discs Adams, John Luther, 1953- Become Desert. 1 CDs 1 DVDs $19.98 Brooklyn, NY: Cantaloupe ©2019 CA 21148 2 713746314828 Ludovic Morlot conducts the Seattle Symphony. Includes one CD, and one video disc with a 5.1 surround sound mix. http://www.tfront.com/p-476866-become-desert.aspx Canticles of The Holy Wind. $16.98 Brooklyn, NY: Cantaloupe ©2017 CA 21131 2 713746313128 http://www.tfront.com/p-472325-canticles-of-the-holy-wind.aspx Adams, John, 1947- John Adams Album / Kent Nagano. $13.98 New York: Decca Records ©2019 DCA B003108502 2 028948349388 Contents: Common Tones in Simple Time -- 1. First Movement -- 2. the Anfortas Wound -- 3. Meister Eckhardt and Quackie -- Short Ride in a Fast Machine. Nagano conducts the Orchestre Symphonique de Montreal. http://www.tfront.com/p-482024-john-adams-album-kent-nagano.aspx Ades, Thomas, 1971- Colette [Original Motion Picture Soundtrack]. $14.98 Lake Shore Records ©2019 LKSO 35352 2 780163535228 Music from the film starring Keira Knightley. http://www.tfront.com/p-476302-colette-[original-motion-picture-soundtrack].aspx Agnew, Roy, 1891-1944. Piano Music / Stephanie McCallum, Piano. $18.98 London: Toccata Classics ©2019 TOCC 0496 5060113444967 Piano music by the early 20th century Australian composer. http://www.tfront.com/p-481657-piano-music-stephanie-mccallum-piano.aspx Aharonian, Coriun, 1940-2017. Carta. $18.98 Wien: Wergo Records ©2019 WER 7374 2 4010228737424 The music of the late Uruguayan composer is performed by Ensemble Aventure and SWF-Sinfonieorchester Baden-Baden. http://www.tfront.com/p-483640-carta.aspx Ahmas, Harri, 1957- Organ Music / Jan Lehtola, Organ. -

Písecké Gymnáziu V Letech 1778-1850

JIHO ČESKÁ UNIVERZITA V ČESKÝCH BUD ĚJOVICÍCH FILOZOFICKÁ FAKULTA HISTORICKÝ ÚSTAV DIPLOMOVÁ PRÁCE PÍSECKÉ GYMNÁZIUM V LETECH 1778-1850 Vedoucí práce: doc. PhDr. Miroslav Novotný, CSc. Autor práce: Kristýna Pichlíková Studijní obor: Kulturní historie 2009 Prohlašuji, že svoji diplomovou práci jsem vypracovala samostatn ě pouze s použitím pramen ů a literatury uvedených v seznamu citované literatury. Prohlašuji, že v souladu s § 47b zákona č. 111/1998 Sb., v platném zn ění, souhlasím se zve řejn ěním své diplomové práce, a to v nezkrácené podob ě elektronickou cestou ve ve řejn ě p řístupné části databáze STAG provozované Jiho českou univerzitou v Českých Bud ějovicích na jejích internetových stránkách. České Bud ějovice, 24. dubna 2009 Za cenné rady a trp ělivost d ěkuji doc. PhDr. Miroslavu Novotnému, CSc. a pracovník ům Státního okresního archivu v Písku. ANOTACE Náplní této diplomové práce je vývoj píseckého gymnázia v letech 1778-1850. Práce vznikla na základ ě studia odborné literatury a pramen ů uložených ve Státním okresním archivu v Písku. První část práce se zabývá stru čnými d ějinami m ěsta Písku, hlavní d ůraz je p řitom kladen na vznik gymnázia. Nejsou zde opomenuty ani ostatní st řední školy, které vznikly v Písku v devatenáctém století. Hlavní část práce je zam ěř ena na samotné písecké gymnázium, p řičemž veškeré poznatky jsou dávány do kontextu d ějin vzd ělanosti a samotného m ěsta. Analýza školy je p ředevším zam ěř ena na studenty. Zaznamenává nejen jejich po čet, ale také prosp ěch a dobu jejich studia. Není opomenut ani jejich teritoriální a sociální původ, který je zkoumán z hlediska zam ěstnání otc ů. -

Západočeská Univerzita V Plzni Fakulta Filozofická Diplomová Práce

Západočeská univerzita v Plzni Fakulta filozofická Diplomová práce Plzeň 2017 Alžběta Bergerová Západočeská univerzita v Plzni Fakulta filozofická Diplomová práce Tvrze na jižním Plzeňsku Alžběta Bergerová Plzeň 2017 Západočeská univerzita v Plzni Fakulta filozofická Katedra archeologie Studijní program: Archeologie Studijní obor: Archeologie Diplomová práce Tvrze na jižním Plzeňsku Alžběta Bergerová Vedoucí práce: PhDr. Josef Hložek, Ph.D. Katedra archeologie Fakulta filozofická Západočeské univerzity v Plzni Plzeň 2017 Prohlašuji, že jsem práci zpracovala samostatně a použila jen uvedených pramenů a literatury. Plzeň, 2017 ……………………………… Na tomto místě bych chtěla poděkovat vedoucímu mé diplomové práce, panu PhDr. Josefovi Hložkovi, Ph.D. za trpělivost, konzultace a cenné poznatky, které mi umožnily zpracovat mou diplomovou práci. Dále bych ráda poděkovala mým spolužákům, zejména kolegyním Mgr. Veronice Rohanové a Bc. Lucii Moravcové za jejich pomoc při práci na terénním průzkumu a za četné diskuse k tématu. Velmi si vážím i poskytnuté podpory od dalších svých přátel a rodiny, bez jejichž porozumění by tato práce mohla jen obtížně vzniknout. Obsah 1 ÚVOD ......................................................................................... 1 2 TVRZE – TERMINOLOGIE, TYPOLOGIE .................................. 2 2.1 Terminologie ................................................................................ 2 2.2 Typologie ...................................................................................... 3 2.2.1 Typologie tvrzí -

22. Koeficient Ekologické Stability

22. KOEFICIENT EKOLOGICKÉ STABILITY Myslín Březí Horosedly Předmíř Mirovice Slapsko Šebířov Bělčice Lety Kožlí Kovářov Hornosín Mišovice Nerestce Oldřichov Vilice Uzeničky Orlík nad Vltavou Kocelovice Hrazany Chyšky Lnáře Minice Králova LhotaProbulov Uzenice Zhoř u Mladé Vožice Běleč Rakovice Nová Ves u Mladé Vožice ChlumBezdědovice Kostelec nad Vltavou Nadějkov Hajany Myštice Chobot Čimelice Nevězice Hrejkovice Zhoř Nemyšl Boudy Přeborov Vlksice Řemíčov Tchořovice BorotínSudoměřice u Tábora Smilovy Hory Blatná Přeštěnice Jistebnice Hlasivo Buzice Smetanova Lhota Jickovice Milevsko Mladá Vožice Kadov Zbelítov Jedlany Lom Varvažov Mirotice Osek Dolní Hrachovice Mačkov Milevsko Chotoviny Rodná PojbukyZadní Střítež Lažánky Škvořetice Zvíkovské PodhradíKučeř Božetice Radkov Cerhonice Ostrovec PohnánecPohnání Bradáčov Záboří Balkova Lhota Košín Čečelovice Květov Ratibořské Hory OkrouhláSepekov DrhoviceMeziříčí Svrabov Vodice Bratronice Sedlice Vráž Oslov Lažany Branice Opařany Předotice Křižanov Dražice Mečichov Doubravice JetěticeStehlovice Řepeč Tábor Dolní Hořice Hlupín Vojníkov Veselíčko Zběšičky Velká Turná Čížová Vlastec Chýnov TřebohosticeChrášťovice Podolí IKřenovice Dražičky Radomyšl Drhovle Záhoří Slapy Střelské Hoštice Bernartice Stádlec Bečice Radimovice u Želče Mnichov Vrcovice TemešvárOlešná Nová Ves u Chýnova Únice Osek Libějice Sezimovo Ústí Horní Poříčí Dolní Novosedly Rataje Dobev Lom Turovec Radenín Krty-HradecDroužetice Borovany Malšice Zhoř u Tábora KaleniceKladruby Slabčice Katovice ŘepiceRovnáPřešťovice Kluky Dobronice -

O Du Mein Österreich: Patriotic Music and Multinational Identity in The

O du mein Österreich: Patriotic Music and Multinational Identity in the Austro-Hungarian Empire by Jason Stephen Heilman Department of Music Duke University Date: _______________________ Approved: ______________________________ Bryan R. Gilliam, Supervisor ______________________________ Scott Lindroth ______________________________ James Rolleston ______________________________ Malachi Hacohen Dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Music in the Graduate School of Duke University 2009 ABSTRACT O du mein Österreich: Patriotic Music and Multinational Identity in the Austro-Hungarian Empire by Jason Stephen Heilman Department of Music Duke University Date: _______________________ Approved: ______________________________ Bryan R. Gilliam, Supervisor ______________________________ Scott Lindroth ______________________________ James Rolleston ______________________________ Malachi Hacohen An abstract of a dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Music in the Graduate School of Duke University 2009 Copyright by Jason Stephen Heilman 2009 Abstract As a multinational state with a population that spoke eleven different languages, the Austro-Hungarian Empire was considered an anachronism during the age of heightened nationalism leading up to the First World War. This situation has made the search for a single Austro-Hungarian identity so difficult that many historians have declared it impossible. Yet the Dual Monarchy possessed one potentially unifying cultural aspect that has long been critically neglected: the extensive repertoire of marches and patriotic music performed by the military bands of the Imperial and Royal Austro- Hungarian Army. This Militärmusik actively blended idioms representing the various nationalist musics from around the empire in an attempt to reflect and even celebrate its multinational makeup. -

Mezinárodní Festival Dechových Hudeb Praha International Festival of Wind Orchestras Prague 16.2

8 MEZINÁRODNÍ FESTIVAL DECHOVÝCH HUDEB PRAHA INTERNATIONAL FESTIVAL OF WIND ORCHESTRAS PRAGUE 16.2. – 17.2.2018 PROGRAM FESTIVALU/ FESTIVAL PROGRAMME PÁTEK 16.2./FRIDAY 16th FEBRUARY 2018 Hotel Pyramida, Kongresový sál/ Hotel Pyramida, Congress hall, Bělohorská 24, Praha 6 soutěžní přehlídka/competition Fanfárové orchestry/Fanfare Orchestras střední třída/middle class 13.30 - 14.10 Fricsay Ferenc Wind Orchestra Maďarsko/Hungary Orchestry harmonie/harmonies střední třída/middle class 14.10 - 14.50 Rēzeknes novada un Jāņa Ivanova Rēzeknes mūzikas vidusskolas Lotyšsko/Latvia pūtēju orķestri 14.50 - 15.30 Sinfonisches Blasorchester der Angelaschule Osnabrück Německo/Germany vyšší třída/higher class 15.30 - 16.15 Sasd Concert Wind Orchestra Maďarsko/Hungary Staroměstská radnice/Old Town Hall, Staroměstské náměstí, praha 1 18,00 přijetí zástupců zúčastněných orchestrů radním Hlavního města Prahy meeting of orchestra´s representatives with a councilor of the City of Prague pouze pro účastníky/for participants only Hotel Pyramida, Kongresový sál/ Hotel Pyramida, Congress hall, Bělohorská 24, Praha 6 koncert zahraničních orchestrů / concert of foreign orchestras 19.30 - 20.00 Musikverein Enzenkirchen Rakousko/Austria 20.00 - 20.30 Sasd Concert Wind Orchestra Maďarsko/Hungary 20.30 - 21.00 Landesjugendblasorchester Oberösterreich Rakousko/Austria pro veřejnost vstup volný /free entry SOBOTA 17.2./SATURDAY 17th FEBRUARY 2018 Chrám sv. Mikuláše/St. Nicholaus Church, Staroměstské náměstí, Old Town Square soutěžní přehlídka/competition koncertní vystoupení -

HAVE GERMAN WILL TRAVEL Getranke

HAVE GERMAN WILL TRAVEL Getranke Was trinken die Deutschen? das Bier, die Biere type of beer: die Bierart, die Bierarten bottom-fermented beers: untergarige Biere bottom-fermented (beer usually drunk in Germany and anywhere else) Vollbier types • Lager beer ("ein Bier") • Export beer (,,ein Ex", ,,ein Export" • Pilsener (,,ein Pils", Pilsener Brauart) Miinchener. The internationally-accepted Bock. A strong bottom-fermented beer name for a dark-brown, bottom-fermented originating from Lower Saxony, but now beer which is malty without being exces more strongly associated with Munich. sively sweet. The name arises from the Most countries' bock is dark-brown in development of this style in Munich in the colour, but Germany has many paler second half of the 19th century. In its home examples. The style has seasonal associa city, such a beer would be specified as a tions, with the month of May (Maibock), dunkel, to distinguish it from the more and with autumn. Often labelled with a common golden-coloured belles. In either goat symbol. Bock means a male goat in colour Miinchener beers are still character various Germanic languages. Beer should ized b; their malty palate. Alcoholic con have a density of not less than 16-0 degrees tent by volume: 4·0--4·75 per cent. Dark Plato. Alcoholic content by volume: not Miincheners should be served at cellar less than 6·0 per cent. Serve at room temperatures. should be gently chilled. Helles temperature or lightly chilled, according to taste. Vienna. An ;mber-coloured, bottom fermented beer of above-average stren,gth. Doppelbock. Extra-strong bottom The designation Vienna for this s~yle is _now fermented beer first brewed by Italian found only occasionally, notably 10 Laun monks in Bavaria.