9 Changing Rabbinic Views

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jews and Christians: Perspectives on Mission the Lambeth-Jewish Forum

Jews and Christians: Perspectives on Mission The Lambeth-Jewish Forum Reuven Silverman, Patrick Morrow and Daniel Langton Jews and Christians: Perspectives on Mission The Lambeth-Jewish Forum Both Christianity and Judaism have a vocation to mission. In the Book of the Prophet Isaiah, God’s people are spoken of as a light to the nations. Yet mission is one of the most sensitive and divisive areas in Jewish-Christian relations. For Christians, mission lies at the heart of their faith because they understand themselves as participating in the mission of God to the world. As the recent Anglican Communion document, Generous Love, puts it: “The boundless life and perfect love which abide forever in the heart of the Trinity are sent out into the world in a mission of renewal and restoration in which we are called to share. As members of the Church of the Triune God, we are to abide among our neighbours of different faiths as signs of God’s presence with them, and we are sent to engage with our neighbours as agents of God’s mission to them.”1 As part of the lifeblood of Christian discipleship, mission has been understood and worked out in a wide range of ways, including teaching, healing, evangelism, political involvement and social renewal. Within this broad and rich understanding of mission, one key aspect is the relation between mission and evangelism. In particular, given the focus of the Lambeth-Jewish Forum, how does the Christian understanding of mission affects relations between Christianity and Judaism? Christian mission and Judaism has been controversial both between Christians and Jews, and among Christians themselves. -

Wertheimer, Editor Imagining the Seth Farber an American Orthodox American Jewish Community Dreamer: Rabbi Joseph B

Imagining the American Jewish Community Brandeis Series in American Jewish History, Culture, and Life Jonathan D. Sarna, Editor Sylvia Barack Fishman, Associate Editor For a complete list of books in the series, visit www.upne.com and www.upne.com/series/BSAJ.html Jack Wertheimer, editor Imagining the Seth Farber An American Orthodox American Jewish Community Dreamer: Rabbi Joseph B. Murray Zimiles Gilded Lions and Soloveitchik and Boston’s Jeweled Horses: The Synagogue to Maimonides School the Carousel Ava F. Kahn and Marc Dollinger, Marianne R. Sanua Be of Good editors California Jews Courage: The American Jewish Amy L. Sales and Leonard Saxe “How Committee, 1945–2006 Goodly Are Thy Tents”: Summer Hollace Ava Weiner and Kenneth D. Camps as Jewish Socializing Roseman, editors Lone Stars of Experiences David: The Jews of Texas Ori Z. Soltes Fixing the World: Jewish Jack Wertheimer, editor Family American Painters in the Twentieth Matters: Jewish Education in an Century Age of Choice Gary P. Zola, editor The Dynamics of American Jewish History: Jacob Edward S. Shapiro Crown Heights: Rader Marcus’s Essays on American Blacks, Jews, and the 1991 Brooklyn Jewry Riot David Zurawik The Jews of Prime Time Kirsten Fermaglich American Dreams and Nazi Nightmares: Ranen Omer-Sherman, 2002 Diaspora Early Holocaust Consciousness and and Zionism in Jewish American Liberal America, 1957–1965 Literature: Lazarus, Syrkin, Reznikoff, and Roth Andrea Greenbaum, editor Jews of Ilana Abramovitch and Seán Galvin, South Florida editors, 2001 Jews of Brooklyn Sylvia Barack Fishman Double or Pamela S. Nadell and Jonathan D. Sarna, Nothing? Jewish Families and Mixed editors Women and American Marriage Judaism: Historical Perspectives George M. -

Grantees and Their Funders How Professionals at Jewish Not-For-Profits Experience Working with Grantmakers

Grantees and Their Funders How Professionals at Jewish Not-for-Profits Experience Working with Grantmakers JACK WERTHEIMER March 8, 2021 Dear Friend, “Grantees and Their Funders” by Professor Jack Wertheimer was first published a year ago, but we are re-issuing it now to mark the launch of the project it inspired: GrantED. GrantED: Stronger Relationships, Greater Impact is a joint project of Jewish Funders Network and UpStart designed to strengthen relationships between Jewish philanthropists and the Jewish nonprofit sector, specifically between grantmakers and grantseekers, so we can share in the work of building and sustaining a vibrant Jewish community. GrantED (jgranted.org) creates and curates articles, tools, and other materials to inspire and inform grantmakers and grantseekers in the Jewish community, organizing around four core interdependent components of successful grantmaking partnerships: strengthening relationships, understanding and addressing power dynamics, sustaining impact, effective communication. GrantED also offers workshops, facilitated conversations and other programs. To learn more visit jgranted.org and sign up for its email list here. Based on interviews with 140 senior professionals at North American Jewish not-for-profits, “Grantees and Their Funders” provides a rare opportunity to hear honest feedback from those who might otherwise be reluctant to speak openly. While these professionals reported largely positive experiences with funders, they also shared feedback that we believe is important to address to ensure that Jewish resources are used as efficiently as possible and that the Jewish nonprofit sector is adequately supported in its important work serving the Jewish community. Funders and Jewish professionals are interdependent; while the community cannot function without philanthropic support, funders rely on the expertise and hard work of nonprofit professionals as partners in bringing goals and dreams to fruition. -

Oral Tradition in the Writings of Rabbinic Oral Torah: on Theorizing Rabbinic Orality

Oral Tradition, 14/1 (1999): 3-32 Oral Tradition in the Writings of Rabbinic Oral Torah: On Theorizing Rabbinic Orality Martin S. Jaffee Introduction By the tenth and eleventh centuries of the Common Era, Jewish communities of Christian Europe and the Islamic lands possessed a voluminous literature of extra-Scriptural religious teachings.1 Preserved for the most part in codices, the literature was believed by its copyists and students to replicate, in writing, the orally transmitted sacred tradition of a family tree of inspired teachers. The prophet Moses was held to be the progenitor, himself receiving at Sinai, directly from the mouth of the Creator of the World, an oral supplement to the Written Torah of Scripture. Depositing the Written Torah for preservation in Israel’s cultic shrine, he had transmitted the plenitude of the Oral Torah to his disciples, and they to theirs, onward in an unbroken chain of transmission. That chain had traversed the entire Biblical period, survived intact during Israel’s subjection to the successive imperial regimes of Babylonia, Persia, Media, Greece, and Rome, and culminated in the teachings of the great Rabbinic sages of Byzantium and Sasanian Babylonia. The diverse written recensions of the teachings of Oral Torah themselves enjoyed a rich oral life in the medieval Rabbinic culture that 1 These broad chronological parameters merely represent the earliest point from which most surviving complete manuscripts of Rabbinic literature can be dated. At least one complete Rabbinic manuscript of Sifra, a midrashic commentary on the biblical book of Leviticus (MS Vatican 66), may come from as early as the eighth century. -

Recent Trends in Jewish Food History Writing

–8– “Bread from Heaven, Bread from the Earth”: Recent Trends in Jewish Food History Writing Jonathan Brumberg-Kraus Over the last thirty years, Jewish studies scholars have turned increasing attention to food and meals in Jewish culture. These studies fall more or less into two different camps: (1) text-centered studies that focus on the authors’ idealized, often prescrip- tive construction of the meaning of food and Jewish meals, such as biblical and postbiblical dietary rules, the Passover Seder, or food in Jewish mysticism—“bread from heaven”—and (2) studies of the “performance” of Jewish meals, particularly in the modern period, which often focus on regional variations, acculturation, and assimilation—“bread from the earth.”1 This breakdown represents a more general methodological split that often divides Jewish studies departments into two camps, the text scholars and the sociologists. However, there is a growing effort to bridge that gap, particularly in the most recent studies of Jewish food and meals.2 The major insight of all of these studies is the persistent connection between eating and Jewish identity in all its various manifestations. Jews are what they eat. While recent Jewish food scholarship frequently draws on anthropological, so- ciological, and cultural historical studies of food,3 Jewish food scholars’ conver- sations with general food studies have been somewhat one-sided. Several factors account for this. First, a disproportionate number of Jewish food scholars (compared to other food historians) have backgrounds in the modern academic study of religion or rabbinical training, which affects the focus and agenda of Jewish food history. At the Oxford Symposium on Food and Cookery, my background in religious studies makes me an anomaly. -

Judaism: a Supplemental Resource for Grade 12 World of Religions: A

Change and Evolution Stages in the Development of Judaism: A Historical Perspective As the timeline chart presented earlier demonstrates, the development of the Jewish faith and tradition which occurred over thousands of years was affected by a number of developments and events that took place over that period. As with other faiths, the scriptures or oral historical records of the development of the religion may not be supported by the contemporary archaeological, historical, or scientific theories and available data or artifacts. The historical development of the Jewish religion and beliefs is subject to debate between archeologists, historians, and biblical scholars. Scholars have developed ideas and theories about the development of Jewish history and religion. The reason for this diversity of opinion and perspectives is rooted in the lack of historical materials, and the illusive nature, ambiguity, and ambivalence of the relevant data. Generally, there is limited information about Jewish history before the time of King David (1010–970 BCE) and almost no reliable biblical evidence regarding what religious beliefs and behaviour were before those reflected in the Torah. As the Torah was only finalized in the early Persian period (late 6th–5th centuries BCE), the evidence of the Torah is most relevant to early Second Temple Judaism. As well, the Judaism reflected in the Torah would seem to be generally similar to that later practiced by the Sadducees and Samaritans. By drawing on archeological information and the analysis of Jewish Scriptures, scholars have developed theories about the origins and development of Judaism. Over time, there have been many different views regarding the key periods of the development of Judaism. -

Judaism Volume 52 • Number3 • Spring 2000

CONSERVATIVE JUDAISM VOLUME 52 • NUMBER3 • SPRING 2000 A Publication of the Rabbinical Assembly Vernon Kurtz, President ' ·and the Jewish Theological Seminary Ismar Schorsch, Chancellor ARTI~ TheG EDITORIAL BOARD Hayim Benjamin Edidin Scolnic MartinS. Cohen Refusa Chairman Chairman, Publications Committee Adina Solom1 Amy Gottlieb ~ Bradley Shavit Anson '· Avrah. Managing Editor Henry Balser The EJ Debra S. Cantor Bernard Glassman Aryeh Nina Beth Cardin Editorial Consultant The Rc David G. Dalin G.Da1 Shamai Kanter Stephen C. Lerner BreakiJ PAST EDITORS Michael Panitz Marti1. Charles Simon Leon S. Lang 1;7"r, 1945-1952 Curioru Jack Wertheimer Samuel H. Dresner 1;7"r, 1955-1964 Avram Jack Riemer, 1964-1965 Celebr: Bernard Glassman S. Gershon Levi 1;7"r, 1965-1969 Book Review Editor Mordecai Waxman, 1969-1974 BOOE Stephen C. Lerner, 1974-1977 Bernard Howard Addison Myron Fenster, 1977-1979 To Come Samuel H. Dresner Arthur A. Chiel 1;7 .. r, 1979-1980 By Abral Elliot B. Gertel Harold S. Kushner, 1980-1984 Reviewe< Lawrence Troster David WolfSilverman, 1984-1989 Sacred E1 Contributing Editors Shamai Kanter, 1989-1993 By Steph Reviewe' Living in By Irvin~ Reviewe' Judaism_ By EugeJ Reviewe< COM11 Celebrating l 00 Years of the Rabbinical Assetnbly -l1il~ 'TO ,~,~~,n~ ~,il .C1'TZl ~1111 C1'TZl Jil1~ .il11I1' p1p~1 m~1Jil- n~ :1m~ ( Pirkei Avot 1:12) Part Three: Community f:Iallah is a miracle. Every Saturday morning when I lift the two braided loaves on the bimah as I recite the Hamotzi for the congregation, I wonder at the fresh cohesion of the I). allah braids. It seems a miracle to me. -

Kol Shofar Kashrut Policy and Guide Table of Contents

Kol Shofar Kashrut Policy and Guide Table of Contents Policy Introduction 2 Food Preparation in the Kol Shofar Kitchen 2 Community Member Use of the Kitchen 3 Shared Foods / Potlucks 3 Home-Cooked Food / Community Potlucks 3 Field Trips, Off-site Events and Overnights 3 Personal / Individual Consumption 4 Local Kosher Establishments 5 Pre-Approved Caterers and Bakeries Kashrut Glossary 6 Essential Laws 7 Top Ten Kosher Symbols 8 Further Reading 9 1 A Caring Kol Shofar Community Kashrut Guidelines for Synagogue and Youth Education It is possible sometimes to come closer to God when you are involved in material activities like eating and drinking than when you are involved with “religious” activities like Torah study and prayer. - Rabbi Abraham of Slonim, Torat Avot Kol Shofar is a vibrant community comprised of a synagogue and a school. Informed by the standards of the Conservative Movement, we revere the mitzvot (ritual and ethical commandments) both as the stepping-stones along the path toward holiness and as points of interpersonal connection. In this light, mitzvot are manners of spiritual expression that allow each of us to individually relate to God and to one another. Indeed, it is through the mitzvot that we encounter a sacred partnership, linked by a sacred brit (covenant), in which we embrace the gift of life together and strive to make the world more holy and compassionate. Mitzvot, like Judaism itself, are evolving and dynamic and not every one of us will agree with what constitutes each and every mitzvah at each moment; indeed, we embrace and celebrate the diversity of the Jewish people. -

Linking the Silos: How to Accelerate the Momentum in Jewish Education Today

How to Accelerate the Momentum Accelerate to How Linking the Silos: How to Accelerate Linking the Silos: in Jewish Education Today in Jewish Education the Momentum in Jewish Education Today Jack Wertheimer JACK WERTHEIMER Kislev 5766 December 2005 Linking the Silos: How to Accelerate the Momentum in Jewish Education Today JACK WERTHEIMER The Research Team Steven M. Cohen, Hebrew Union College, New York Sylvia Barack Fishman, Brandeis University Shaul Kelner, Brandeis University Jeffrey Kress, Jewish Theological Seminary Alex Pomson, York University and The Hebrew University Riv-Ellen Prell, University of Minnesota Jack Wertheimer, Jewish Theological Seminary, Project Director Project Consultants Alisa Rubin Kurshan and Jacob Ukeles Kislev 5766 December 2005 © Copyright 2005, The AVI CHAI Foundation Table of Contents Executive Summary 1 Acknowledgments 3 Introduction 5 The Current Moment in Jewish Education 7 A More Perfect Union: Families and Jewish Education 8 Multiple Choices Attract Educational Consumers 16 Community Can Trump Demography 23 Policy Implications 27 Parental Choice and the Marketing of Day Schools 27 Investing in Supplementary Schooling 29 Thinking Systemically 30 Opportunities for Policy Makers to Consider 32 Appendix I: The Method and Scope of the Research Projects Undergirding this Study 34 Appendix II: The Research Team 37 List of Figures Figure 1: The Relationship Between a Parent’s Jewish Schooling and Children’s Jewish Education 9 Figure 2: The Impact of a Parent’s Jewish Camp Experience Upon Children’s Jewish Education -

Rabbinic Judaism “Moses Received Torah F

Feminist Sexual Ethics Project Introduction – Rabbinic Judaism “Moses received Torah from Sinai and handed it down to Joshua; and Joshua to the Elders; and the Elders to the Prophets; and the Prophets handed it down to the Men of the Great Assembly…” Mishnah Avot 1:1 Judaism is often believed to be a religion based primarily in the Hebrew Bible, or even more specifically, the first five books of the Bible, known in Jewish tradition as the Torah. These five books, in the form of a Torah scroll, are found in nearly every Jewish house of worship. “Torah,” however, is a term whose meaning can encompass far more than particular books; for Jews, “Torah” often also means the full scope of Jewish learning, law, practice, and tradition. This conception of Torah derives from the rabbis of late antiquity, who developed the belief that the written Torah was accompanied from its earliest transmission by an equally Divine “Oral Torah,” a body of law and explanations of the written Torah that was passed down by religious leaders and scholars through the ages of Jewish history. Thus, Jewish law and religious practices are based in far more than the biblical text. The rabbis considered themselves an integral link in this chain of transmission, and its heirs. In particular, the works produced by the rabbis of late antiquity, from the beginning of the Common Era to the time of the Muslim Conquest, in Roman Palestine and Sassanian Babylonia (modern day Iran/Iraq), have influenced the shape of Judaism to this day. The Talmud (defined below), for example, is considered the essential starting point for any discussion of Jewish law, even more so than the bible. -

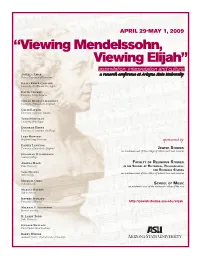

“Viewing Mendelssohn, Viewing Elijah”

APRIL 29-MAY 1, 2009 “Viewing Mendelssohn, Viewing Elijah” assimilation, interpretation and culture Ariella Amar a rreses eearcharch cconferenceonference atat ArizonaArizona StateState UniversityUniversity Hebrew University of Jerusalem Julius Reder Carlson University of California, Los Angeles David Conway University College London Sinéad Dempsey-Garratt University of Manchester, England Colin Eatock University of Toronto, Canada Todd Endelman University of Michigan Deborah Hertz University of California, San Diego Luke Howard Brigham Young University sponsored by Daniel Langton University of Manchester, England JEWISH STUDIES an academic unit of the College of Liberal Arts and Sciences Jonathan D. Lawrence Canisius College Angela Mace FACULTY OF RELIGIOUS STUDIES Duke University IN THE SCHOOL OF HISTORICAL, PHILOSOPHICAL AND RELIGIOUS STUDIES Sara Malena Wells College an academic unit of the College of Liberal Arts and Sciences Michael Ochs Ochs Editorial SCHOOL OF MUSIC an academic unit of the Herberger College of the Arts Marcus Rathey Yale University Jeffrey Sposato University of Houston http://jewishstudies.asu.edu/elijah Michael P. Steinberg Brown University R. Larry Todd Duke University Donald Wallace United States Naval Academy Barry Wiener Graduate Center, City University of New York Viewing Mendelssohn, Viewing Elijah: assimilation, interpretation and culture a research conference at Arizona State University / April 29 – May 1, 2009 Conference Synopsis From child prodigy to the most celebrated composer of his time: Felix Mendelssohn -

Resources to Begin the Study of Jewish Law in Conservative Judaism*

LAW LIBRARY JOURNAL Vol. 105:3 [2013-15] Resources to Begin the Study of Jewish Law in Conservative Judaism* David Hollander** Conservative Judaism stands at the center of the Jewish ideological spectrum. In that position it strives, sometimes with difficulty, to apply a flexible, modern out- look to an ancient system of binding laws. This bibliography provides law scholars with annotated citations to a selection of important sources related to Jewish law in Conservative Judaism, supplemented by brief explanations of the larger context of the resources. Introduction . 305 Historical Development of Conservative Judaism. 307 Primary Sources of Jewish Law in Conservative Judaism. 310 Secondary Sources of Jewish Law in Conservative Judaism. 316 Jewish Law and Conservative Judaism in Israel. 319 Conclusion . 320 Introduction ¶1 Conservative Judaism is an unfortunately named branch of liberal Judaism.1 If Orthodox Judaism stands on one side of the left-right divide of the Jewish com- munity (the right side), Conservative Judaism is firmly on the opposite (left) side. However, if the Jewish community is divided into those who view Jewish law as binding and those who do not, Conservative Judaism (in theory, at least) is firmly on the side of binding law, the same side as Orthodox Judaism. So Conservative Judaism occupies an uncomfortable position, firmly modern and liberal, while still adhering to a binding legal framework, which is a space largely occupied by the nonliberal camp of Orthodox Judaism. ¶2 This middle space is accompanied by many problems, but despite these problems, the conception of Jewish law offered by the Conservative movement represents an important and comprehensive vision that claims for itself a historical authenticity,2 and that is ideally suited to ensure that the exploration of Jewish law * © David Hollander, 2013.