Competitive Implications of Environmental Regulation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Remote Control Code List

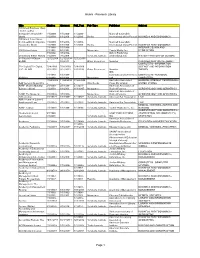

Remote Control Code List MDB1.3_01 Contents English . 3 Čeština . 4 Deutsch . 5 Suomi . 6 Italiano . 7. Nederlands . 8 Русский . .9 Slovenčina . 10 Svenska . 11 TV Code List . 12 DVD Code List . 25 VCR Code List . 31 Audio & AUX Code List . 36 2 English Remote Control Code List Using the Universal Remote Control 1. Select the mode(PVR, TV, DVD, AUDIO) you want to set by pressing the corresponding button on the remote control. The button will blink once. 2. Keep pressing the button for 3 seconds until the button lights on. 3. Enter the 3-digit code. Every time a number is entered, the button will blink. When the third digit is entered, the button will blink twice. 4. If a valid 3-digit code is entered, the product will power off. 5. Press the OK button and the mode button will blink three times. The setup is complete. 6. If the product does not power off, repeat the instruction from 3 to 5. Note: • When no code is entered for one minute the universal setting mode will switch to normal mode. • Try several setting codes and select the code that has the most functions. 3 Čeština Seznam ovládacích kódů dálkového ovladače Používání univerzálního dálkového ovladače 1. Vyberte režim (PVR, TV, DVD, AUDIO), který chcete nastavit, stisknutím odpovídajícího tlačítka na dálkovém ovladači. Tlačítko jednou blikne. 2. Stiskněte tlačítko na 3 sekundy, dokud se nerozsvítí. 3. Zadejte třímístný kód. Při každém zadání čísla tlačítko blikne. Po zadání třetího čísla tlačítko blikne dvakrát. 4. Po zadání platného třímístného kódu se přístroj vypne. -

Especially Economical Household Appliances 2007/08 Consumer Information

Saving on Electricity and Water is Worthwhile Especially Economical Household Appliances 2007/08 Consumer Information Refigerators and For washing machines, 20 liters more water each use freezers, wahsing causes additional costs of 234 € over 15 years. machines and dishwashers, as For refrigerators and freezers, 100 kWh more cause well as washer- additional electricity costs of 225 € over 15 years, plus dryers and driers, possible price increases. The most economical tabletop are purchases refrigerator with */*** compartment saves about 400 € over for many years 15 years, compared with the model with the highest power of service. Along consumption. A higher price of e.g. 200 € is therefore a with good per- very prifitable investment. formance, above This leaflet summarizes especially economical models of all they should the common designs and size classes. It should serve as be reliable and orientation for taking low power and water consumption have a long life. into account. The information is based on market data Furthermore they from August 2007. Should you read this brochure at a should be economical. Low power and water consumption much later time or not find the information you seek here, leads to lower operatoing costs and less environmental please look in the Internet under www.spargeraete.de. In loading this online database, you will find the entire up-to-date For many appliances, the operating costs over their life- German offering known to the authors of this brochure. time are higher than the purchase price. Especially eco- nomic appliances thus save more on power and waters costs over the years than the purchase price. -

Study on the Competitiveness of the EU Gas Appliances Sector

Ref. Ares(2015)2495017 - 15/06/2015 Study on the Competitiveness of the EU Gas Appliances Sector Within the Framework Contract of Sectoral Competitiveness Studies – ENTR/06/054 Final Report Client: Directorate-General Enterprise & Industry Rotterdam, 11 August 2009 Disclaimer: The views and propositions expressed herein are those of the experts and do not necessarily represent any official view of the European Commission or any other organisations mentioned in the Report ECORYS SCS Group P.O. Box 4175 3006 AD Rotterdam Watermanweg 44 3067 GG Rotterdam The Netherlands T +31 (0)10 453 88 16 F +31 (0)10 453 07 68 E [email protected] W www.ecorys.com Registration no. 24316726 ECORYS Macro & Sector Policies T +31 (0)31 (0)10 453 87 53 F +31 (0)10 452 36 60 Table of contents 1 Introduction 1 2 Objectives and policy rationale 5 3 Main findings and conclusions 7 4 The gas appliances sector 11 4.1 Introduction 11 4.2 Definition 11 4.3 Overview of sub-sectors 16 4.3.1 Heating, ventilation and air conditioning (HVAC) 16 4.3.2 Domestic appliances 18 4.3.3 Fittings 20 4.4 The application of statistics 22 4.5 Statistical approach to sector and subsectors 23 5 Key characteristics of the European gas appliances sector 29 5.1 Introduction 29 5.2 Importance of the sector 30 5.2.1 Output 30 5.2.2 Employment 31 5.2.3 Demand 32 5.3 Production, employment, demand and trade within EU 33 5.3.1 Production share EU-27 output per country 33 5.3.2 Employment 39 5.3.3 Demand by Member State 41 5.3.4 Intra EU trade in GA 41 5.4 Industry structure and size distribution -

Fisher & Paykel Appliances Holdings Limited

FISHER & PAYKEL APPLIANCES HOLDINGS LIMITED TARGET COMPANY STATEMENT — IN RELATION TO A TAKEOVER OFFER BY HAIER NEW ZEALAND INVESTMENT HOLDING COMPANY LIMITED — 4 OCTOBER 2012 For personal use only For personal use only COVER: PHASE 7 DISHDRAWER TM DISHWASHER FISHER & PAYKEL APPLIANCES HOLDINGS LIMITED TARGET COMPANY STATEMENT CHAIRMAN’S LETTER 03 TARGET COMPANY STATEMENT (TAKEOVERS CODE DISCLOSURES) 07 SCHEDULE 1 — 4 25 For personal use only APPENDIX: INDEPENDENT ADVISER’S REPORT 37 CHAIRMAN’S LETTER For personal use only CHAIRMAN’S LETTER P3 Dear Shareholder Haier New Zealand Investment Holding Company Limited (“Haier”) has offered $1.20 per share to buy your shares in Fisher & Paykel Appliances Holdings Limited (“FPA”) by means of a formal takeover offer (the Offer“ ”). •• INDEPENDENT DIRECTORS RECOMMEND DO NOT ACCEPT HAIER’S OFFER •• The independent directors of FPA (Dr Keith Turner, Mr Philip Lough, Ms Lynley Marshall and Mr Bill Roest) (the “Independent Directors”) unanimously recommend that shareholders do not accept the Offer from Haier. In making their recommendation, the Independent Directors have carefully considered a full range of expert advice available to them. Therefore you should take no action. The principal reasons for recommending that shareholders do not accept are: _ Having regard to a full range of expert advice now available to the Independent Directors (including the Independent Adviser’s valuation range of $1.28 to $1.57 per FPA Share), the Independent Directors consider that the Offer of $1.20 per FPA Share does not adequately reflect their view of the value of FPA based on their confidence in the strategic direction of the Company; and _ FPA is in a strong financial position and, as the Independent Adviser notes, FPA is at a “relatively early stage of implementation of the company’s comprehensive rebuilding strategy”. -

Research Library Page 1

Alumni - Research Library Title Citation Abstract Full_Text Pub Type Publisher Subject 100 Great Business Ideas : from Leading Companies Around the 1/1/2009- 1/1/2009- 1/1/2009- Marshall Cavendish World 1/1/2009 1/1/2009 1/1/2009 Books International (Asia) Pte Ltd BUSINESS AND ECONOMICS 100 Great Sales Ideas : from Leading Companies 1/1/2009- 1/1/2009- 1/1/2009- Marshall Cavendish Around the World 1/1/2009 1/1/2009 1/1/2009 Books International (Asia) Pte Ltd BUSINESS AND ECONOMICS 1/1/1988- 1/1/1988- INTERIOR DESIGN AND 1001 Home Ideas 6/1/1991 6/1/1991 Magazines Family Media, Inc. DECORATION 3/1/2002- 3/1/2002- Oxford Publishing 20 Century British History 7/1/2009 7/1/2009 Scholarly Journals Limited(England) HISTORY--HISTORY OF EUROPE 33 Charts [33 Charts - 12/12/2009 12/12/2009- 12/12/2009 BLOG] + 6/3/2011 + Other Resources Newstex CHILDREN AND YOUTH--ABOUT COMPUTERS--INFORMATION 50+ Digital [50+ Digital, 7/28/2009- 7/28/2009- 7/28/2009- SCIENCE AND INFORMATION LLC - BLOG] 2/22/2010 2/22/2010 2/22/2010 Other Resources Newstex THEORY IDG 1/1/1988- 1/1/1988- Communications/Peterboro COMPUTERS--PERSONAL 80 Micro 6/1/1988 6/1/1988 Magazines ugh COMPUTERS 11/24/2004 11/24/2004 11/24/2004 Australian Associated GENERAL INTEREST PERIODICALS-- AAP General News Wire + + + Wire Feeds Press Pty Limited UNITED STATES AARP Modern Maturity; 2/1/1988- 2/1/1988- 2/1/1991- American Association of [Library edition] 1/1/2003 1/1/2003 11/1/1997 Magazines Retired Persons GERONTOLOGY AND GERIATRICS American Association of AARP The Magazine 3/1/2003+ 3/1/2003+ Magazines Retired Persons GERONTOLOGY AND GERIATRICS ABA Journal 8/1/1972+ 1/1/1988+ 1/1/1992+ Scholarly Journals American Bar Association LAW ABA Journal of Labor & Employment Law 7/1/2007+ 7/1/2007+ 7/1/2007+ Scholarly Journals American Bar Association LAW MEDICAL SCIENCES--NURSES AND ABNF Journal 1/1/1999+ 1/1/1999+ 1/1/1999+ Scholarly Journals Tucker Publications, Inc. -

Corporate Responsibility Report 2008

Corporate Responsibility Report 2008 Strength through responsibility Summary Reed Elsevier Corporate Responsibility Report 2008 Chief Executive’s introduction Governance People Our true performance as a company must take account of both our non-financial and financial results. They are intrinsically linked – if we want to be a profitable and successful company, we must be an ethical one. We are committed to being both. To that end, we have been building on our expertise and engaging with stakeholders to find ways to innovate and improve. Health and safety In developing online solutions to the needs of our customers in areas like health, science and technology, law, environment, and business, we benefit society. For example, Procedures Consult gives doctors a way of maintaining their skills and knowledge through web-based simulation of essential medical techniques; TotalPatent is a single source for global patents, a primary driver in research and development; XpertHR helps practitioners advance good practice in people management; energylocate aggregates our energy offerings into a one-stop community, using tools like social networking and video to advance knowledge. Customers Innovation is also helping advance our internal corporate responsibility: > Increased online training in our Code of Ethics and Business Conduct has led to more of our people understanding what it means to do the right thing > A new global jobs board illuminates our value, Boundarylessness, by allowing employees to search for new positions across locations, functions, -

Besonders Sparsame Haushaltsgeräte 2006/07 Eine Verbraucherinformation

Besonders sparsame Haushaltsgeräte 2006/07 Eine Verbraucherinformation Kühl- und Gefrier- Bei Waschmaschinen verursacht ein um 20 Liter höherer geräte, Wasch- Wasserverbrauch in 15 Jahren 234 € an Mehrkosten. Bei u n d S p ü l m a - Kühl- und Gefriergeräten kosten 100 kWh jährlicher Mehr- schinen sowie verbrauch in 15 Jahren 225 € zusätzliche Stromkosten Waschtrockner zzgl. evtl. Preissteigerungen. Der sparsamste Tischkühl- und Wäschetrock- schrank mit */*** Sterne-Fach spart z.B. gegenüber dem ner sind Anschaf- am meisten Strom verbrauchenden Modell in 15 Jahren fungen für viele insgesamt rund 400 € an Stromkosten. Ein Mehrpreis Jahre. Neben gu- beim Kauf von z.B. 200 € ist insofern eine sehr rentable ter Leistung sol- Investition. len sie vor allem In diesem Faltblatt sind besonders sparsame Modelle zuverlässig sein üblicher Bauarten und Größenklassen zusammengestellt. und eine lange Le- Es soll als Orientierung dienen, wenn man auf niedrigen bensdauer haben. Strom- und Wasserverbrauch achten will. Seine Angaben Außerdem sollen basieren auf Marktdaten von August 2006. Falls Sie diese sie sparsam sein. Ein niedriger Strom- oder Wasserver- Broschüre erst wesentlich später lesen oder wenn Sie die brauch verursacht weniger Betriebskosten und entlastet von Ihnen gewünschten Informationen hier nicht finden, die Umwelt. Bei vielen Geräten sind die Betriebskosten schauen Sie im Internet auf www.spargeraete.de. In die- in ihrer Lebensdauer deutlich höher als ihr Kaufpreis. ser Online-Datenbank finden Sie das gesamte deutsche Besonders sparsame Geräte sparen deshalb im Laufe Lieferangebot auf dem jeweils aktuellsten Stand, der den der Jahre wesentlich mehr an Strom- und Wasserkosten Verfassern dieser Broschüre bekannt ist. ein, als sie bei der Anschaffung teurer sind. -

IN the UNITED STATES BANKRUPTCY COURT for the EASTERN DISTRICT of VIRGINIA RICHMOND DIVISION ) in Re

Case 21-30209-KRH Doc 349 Filed 03/26/21 Entered 03/26/21 21:03:19 Desc Main Document Page 1 of 172 IN THE UNITED STATES BANKRUPTCY COURT FOR THE EASTERN DISTRICT OF VIRGINIA RICHMOND DIVISION ) In re: ) Chapter 11 ) ALPHA MEDIA HOLDINGS LLC, et al.,1 ) Case No. 21-30209 (KRH) ) Debtors. ) (Jointly Administered) ) CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE I, Julian A. Del Toro, depose and say that I am employed by Stretto, the claims and noticing agent for the Debtors in the above-captioned cases. On March 15, 2021, at my direction and under my supervision, employees of Stretto caused the following document to be served via first-class mail on the service list attached hereto as Exhibit A, and via electronic mail on the service list attached hereto as Exhibit B: • Notice of Filing of Plan Supplement (Docket No. 296) Furthermore, on March 15, 2021, at my direction and under my supervision, employees of Stretto caused the following document to be served via first-class mail on the service list attached hereto as Exhibit C: • Notice of Filing of Plan Supplement (Docket No. 296 – Notice Only) Dated: March 26, 2021 /s/Julian A. Del Toro Julian A. Del Toro STRETTO 410 Exchange, Suite 100 Irvine, CA 92602 Telephone: 855-395-0761 Email: [email protected] 1 The Debtors in these chapter 11 cases, along with the last four digits of each debtor’s federal tax identification number, are: Alpha Media Holdings LLC (3634), Alpha Media USA LLC (9105), Alpha 3E Corporation (0912), Alpha Media LLC (5950), Alpha 3E Holding Corporation (9792), Alpha Media Licensee LLC (0894), Alpha Media Communications Inc. -

CA - FACTIVA - SP Content

CA - FACTIVA - SP Content Company & Financial Congressional Transcripts (GROUP FILE Food and Drug Administration Espicom Company Reports (SELECTED ONLY) Veterinarian Newsletter MATERIAL) (GROUP FILE ONLY) Election Weekly (GROUP FILE ONLY) Health and Human Services Department Legal FDCH Transcripts of Political Events Military Review American Bar Association Publications (GROUP FILE ONLY) National Endowment for the Humanities ABA All Journals (GROUP FILE ONLY) General Accounting Office Reports "Humanities" Magazine ABA Antitrust Law Journal (GROUP FILE (GROUP FILE ONLY) National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and ONLY) Government Publications (GROUP FILE Alcoholism's Alcohol Research & ABA Banking Journal (GROUP FILE ONLY): Health ONLY) Agriculture Department's Economic National Institute on Drug Abuse NIDA ABA Business Lawyer (GROUP FILE Research Service Agricultural Outlook Notes ONLY) Air and Space Power Journal National Institutes of Health ABA Journal (GROUP FILE ONLY) Centers for Disease Control and Naval War College Review ABA Legal Economics from 1/82 & Law Prevention Public Health and the Environment Practice from 1/90 (GROUP FILE ONLY) CIA World Factbook SEC News Digest ABA Quarterly Tax Lawyer (GROUP FILE Customs and Border Protection Today State Department ONLY) Department of Energy Documents The Third Branch ABA The International Lawyer (GROUP Department of Energy's Alternative Fuel U.S. Department of Agricultural FILE ONLY) News Research ABA Tort and Insurance Law Journal Department of Homeland Security U.S. Department of Justice's -

Strom Und Wasser Sparen Lohnt Sich

StromStrom undund WasserWasser sparensparen lohntlohnt sichsich Besonders sparsame Haushaltsgeräte 1999 Eine Verbraucherinformation Kühl- und Gefriergeräte, Wasch- und Spülmaschinen so- und ein um 20 Liter höherer Wasserverbrauch kostet in wie Wäschetrockner sind Anschaffungen für viele Jahre. 15 Jahren vermeidbare 374 DM. Tischkühlschränke ohne Neben guter Leistung sollen sie vor allem zuverlässig Sternefach verbrauchen z.B. sein und eine lange Lebensdauer haben. Außerdem sol- zwischen 0,29 und 0,81 kWh len sie sparsam sein. Ein niedriger Strom- oder Wasser- pro Tag. Diese Differenz von verbrauch bewirkt nicht nur weniger Umweltbelastung, 0,52 kWh pro Tag macht in sondern spart auch Betriebskosten. Bei vielen Geräten 15 Jahren 854 DM zusätzli- sind die Betriebskosten in ih- che Stromkosten aus. Das ist rer Lebensdauer deutlich hö- wesentlich mehr als die ca. her als ihr Kaufpreis. Beson- 300 DM, die ein besonders ders sparsame Geräte kön- sparsames Gerät beim Kauf nen deshalb im Lauf der Jah- mehr kostet. re wesentlich mehr an Strom- In diesem Faltblatt sind be- und Wasserkosten einsparen, sonders sparsame Modelle als sie bei der Anschaffung üblicher Bauarten und Grö- teurer sind. ßenklassen zusammenge- In Deutschland werden 1999 stellt. Es soll Menschen, die im Handel etwa 2300 Kühl- auf niedrigen Strom- und und Gefriergeräte, 680 Wasserverbrauch achten Waschmaschinen, 530 Spül- wollen, als Orientierung maschinen, 200 Wäsche- beim Gerätekauf dienen. trockner und 75 Waschtrockner angeboten. Darunter gibt Sparsamkeit und Euro-Label Seite 2 es einige besonders sparsame Modelle, viele mit mittle- Kühlschränke Seite 3 ren und ebenfalls viele mit sehr hohen Strom- und Was- Gefriergeräte Seite 9 serverbräuchen. Waschmaschinen Seite 11 Waschtrockner Seite 12 Die Verbrauchsunterschiede erscheinen oft als "Stellen Trockner Seite 13 hinter dem Komma". -

Besonders Sparsame Haushaltsgeräte 2013/14 Eine Verbraucherinformation

Besonders sparsame Haushaltsgeräte 2013/14 Eine Verbraucherinformation Kühl- und Gefrier- Bei Waschmaschinen verursacht ein um 20 Liter höhe- geräte, Wasch- und rer Wasserverbrauch in 15 Jahren 388 € Mehrkosten. Spülmaschinen so- Bei Kühl- und Gefriergeräten kosten 100 kWh jährlicher wie Waschtrockner Mehrverbrauch in 15 Jahren 420 € zusätzliche Strom- und Wäschetrock- kosten zzgl. evtl. Preissteigerungen. Die sparsamste ner sind Anschaf- Kühl-Gefrier-Kombination mit 200-250 Litern spart z.B. fungen für viele gegenüber dem am meisten Strom verbrauchenden Jahre. Neben guter Modell in 15 Jahren insgesamt 1.200 € an Stromkosten. Leistung sollen sie Ein Mehrpreis beim Kauf von z.B. 450 € ist insofern eine vor allem zuverläs- sehr rentable Investition. sig sein und eine In diesem Faltblatt sind besonders sparsame Modelle lange Lebensdauer üblicher Bauarten und Größenklassen zusammengestellt. haben. Es soll als Orientierung dienen, wenn man auf niedrigen Außerdem sollen sie sparsam sein. Ein niedriger Strom- Strom- und Wasserverbrauch achten will. Seine Angaben oder Wasserverbrauch verursacht weniger Betriebskosten basieren auf Marktdaten von Oktober 2013. Falls Sie diese und entlastet die Umwelt. Bei vielen Geräten sind die Broschüre erst wesentlich später lesen oder wenn Sie die Betriebskosten in ihrer Lebensdauer deutlich höher als ihr von Ihnen gewünschten Informationen hier nicht finden, Kaufpreis. Besonders sparsame Geräte sparen deshalb schauen Sie im Internet auf www.spargeraete.de. In die- im Laufe der Jahre wesentlich mehr an Strom- und Was- ser Online-Datenbank finden Sie das gesamte deutsche serkosten ein, als sie bei der Anschaffung teurer sind. Lieferangebot auf dem jeweils aktuellsten Stand, der den Verfassern dieser Broschüre bekannt ist. In Deutschland werden im Herbst 2013 im Handel etwa 2400 verschiedene Kühl- und Gefriergeräte, 700 Wasch- Sparsamkeit und Euro-Label Seite 2 maschinen, 1100 Spülmaschinen, 270 Wäschetrockner Kühlschränke Seite 3 und 65 Waschtrockner angeboten. -

Large Residential Washers

Large Residential Washers Investigation No. TA-201-076 Publication 4745 December 2017 U.S. International Trade Commission Washington, DC 20436 U.S. International Trade Commission COMMISSIONERS Rhonda K. Schmidtlein, Chairman David S. Johanson, Vice Chairman Irving A. Williamson Meredith M. Broadbent Catherine DeFilippo Director of Operations Staff assigned Nathanael Comly, Investigator Michael Szustakowski, Investigator Dennis Fravel, Industry Analyst Jeffrey Horowitz, Industry Analyst John Benedetto, Economist David Boyland, Accountant Cynthia Payne, Statistician Russell Duncan, Statistician Karl von Schriltz, Attorney Michael Anderson, Supervisory Investigator Special assistance from Robert Casanova, Investigator Address all communications to Secretary to the Commission United States International Trade Commission Washington, DC 20436 U.S. International Trade Commission Washington, DC 20436 www.usitc.gov Large Residential Washers Investigation No. TA-201-076 Publication 4745 December 2017 CONTENTS Page Determination and Remedy Recommendations ............................................................................ 1 Commission's Views on Injury ........................................................................................................ 3 Commissioners' Views on Remedy ................................................................................................. 65 Remedy Modeling Attachment ....................................................................................................... 81 Part I: Introduction