Copyright Chawton House Library

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Unexpected Animorphs #44 K.A

The Unexpected Animorphs #44 K.A. Applegate Table of Contents Chapter 1 Chapter 2 Chapter 3 Chapter 4 Chapter 5 Chapter 6 Chapter 7 Chapter 8 Chapter 9 Chapter 10 Chapter 11 Chapter 12 Chapter 13 Chapter 14 Chapter 15 Chapter 16 Chapter 17 Chapter 18 Chapter 19 Chapter 20 Chapter 21 Chapter 22 Chapter 23 Chapter 24 Chapter 1 I swooped low. This had to be it. Plane at the far gate. Two Marine guards, trying to look casual. Well, as casual as you can get wearing combat boots and a pistol strapped to your chest. <Jake, I think I found it. Jake?> I circled, flapped my wings to gain altitude. <Rachel? Tobias? Anybody?> An armored truck rumbled toward the plane. The driver stopped, showed one of the guards a clipboard, then backed up to the cargo hold. The rear of the truck opened. Two guys in hooded yellow coveralls climbed out. Pulled oxygen masks over their faces and unlatched the plane's cargo door. Okay. These guys definitely weren't unloading souvenirs from Disneyland. If somebody was transporting a chunk of Bug fighter wreckage, it had to be on this plane. I caught a thermal and rose above the airport. A baggage cart trundled across the tarmac. A jet screamed in for a landing. Guys in jumpsuits and headsets scrambled around, trying to keep the 747's from mowing down the commuter planes. And everywhere I looked - seagulls. On the roof, on the tarmac, against the fence. Seagulls are perfect cover. Part of the landscape, just like pigeons. -

Green Acres School Reading Suggestions for 5Th Or 6Th Graders Updated June 2019

Green Acres School Reading Suggestions for 5th or 6th Graders Updated June 2019 (The books recommended below are part of the Green Acres Library collection. Reading levels and interests vary greatly, so you may want to look also at Reading Suggestions for 4th Graders and Reading Suggestions for 7th/8th Graders.) This list includes: • Fiction • Poetry and Short Stories • Biography and Memoir • Other Nonfiction Graphic books are denoted with the symbol. Fiction Alice, Alex; transl. by Castle In the Stars: The Space Race of 1869 Anne Smith and Owen Smith. "In … this lavishly illustrated graphic novel, Alex Alice delivers a historical fantasy adventure set in a world where man journeyed into space in 1869, not 1969.” Graphic steampunk/Historical fantasy. (Publisher) Appelt, Kathi and Alison McGhee. Maybe a Fox “A fox kit born with a deep spiritual connection to a rural Vermont legend has a special bond with 11-year-old Jules.” Fantasy. (Kirkus Reviews) Avi. The Unexpected Life of Oliver Cromwell Pitts “A 12-year-old boy is left to fend for himself in 18th-century England following a terrible storm and the disappearance of his father… Impossible to put down.” Historical fiction. (Kirkus Reviews) Bauer, Joan. Soar "Sports, friendship, tragedy, and a love connection are all wrapped up in one heartwarming, page-turning story. …This coming-of-age tale features a boy who is courageous and witty; readers—baseball fans or otherwise—will cheer on Jeremiah and this team. The latest middle grade novel from this award-winning author is triumphant and moving." Fiction. (School Library Journal) Beckhorn, Susan. -

Goodbye Consett

GOODBYE CONSETT Excerpts from STORIES FROM A SONGWRITERS LIFE by Steve Thompson Cover image: Mark Mylchreest. Proof reading: Jim Harle (who still calls me Stevie). © 2020 Steve Thompson. All rights reserved. FOREWORD INTO THE UNKOWN By Trev Teasdel (Poet, author and historian) We almost thought of giving in Searching for that distant dream” Steve Thompson, Journey’s End. For a working-class man born in Consett, County Durham, UK apprenticed to the steel industry, with expectations only of the inevitable, Steve Thompson has managed to weld together, over 50 years, an amazing career as hit songwriter, musician, rock band leader, record producer, ideas man, raconteur, radio producer, community media mogul, workshop leader and much more. The world is full of unsung heroes, the people behind the scenes who pull the strings, spark ideas, write the material for others to sing and while Steve may be one of them, his songs at least have been well sung by some of the top artists in show business, and he’s worked alongside some of the top producers of the time. This is what this book is about – those songs that will be familiar to you even if you never knew who wrote them, the stories that lie behind them; the highs and lows, told with honesty, clarity and humour. There’s nothing highfalutin about Steve Thompson, he’s pulled himself up by his own bootstraps, achieved his dream, despite setbacks, and through it remains humble (if a little boastful – as you will see!), a staunchly people’s man with a wicked sense of humour (and I do mean wicked!). -

Paul Schoenfield's' Refractory'method of Composition: a Study Of

Paul Schoenfield's 'Refractory' Method of Composition: A Study of Refractions and Sha’atnez A document submitted to the Graduate School of The University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in the Performance Studies Division of the College-Conservatory of Music by DoYeon Kim B.M., College-Conservatory of Music of The University of Cincinnati, 2011 M.M., Eastman School of Music of The University of Rochester, 2013 Committee Chair: Professor Yehuda Hanani Abstract Paul Schoenfield (b.1947) is a contemporary American composer whose works draw on jazz, folk music, klezmer, and a deep knowledge of classical tradition. This document examines Schoenfield’s characteristic techniques of recasting and redirecting preexisting musical materials through diverse musical styles, genres, and influences as a coherent compositional method. I call this method ‘refraction’, taking the term from the first of the pieces I analyze here: Refractions, a trio for Clarinet, Cello and Piano written in 2006, which centers on melodies from Mozart’s Le nozze di Figaro (The Marriage of Figaro). I will also trace the ‘refraction’ method through Sha’atnez, a trio for Violin, Cello and Piano (2013), which is based on two well-known melodies: “Pria ch’io l’impegno” from Joseph Weigl’s opera L’amor marinaro, ossia il corsaro (also known as the “Weigl tune,” best known for its appearance in the third movement of Beethoven’s Trio for Piano, Clarinet, and Cello in B-flat Major, Op.11 (‘Gassenhauer’)); and the Russian-Ukrainian folk song “Dark Eyes (Очи чёрные).” By tracing the ‘refraction’ method as it is used to generate these two works, this study offers a unified approach to understanding Schoenfield’s compositional process; in doing so, the study both makes his music more accessible for scholarly examination and introduces enjoyable new works to the chamber music repertoire. -

Iasbaba's Monthly Magazine

DECEMBER 2020 IASBABA'S MONTHLY MAGAZINE Controversy surrounding “Love Jihad” Historic Recession: On India’s GDP slump 2020 State Of The Education Report For India India Water Impact 2020 Atmanirbhar Bharat Rojgar Yojana (ABRY) P a g e | 1 PREFACE With the present shift in examination pattern of UPSC Civil Services Examination, ‘General Studies – II and General Studies III’ can safely be replaced with ‘Current Affairs’. Moreover, following the recent trend of UPSC, almost all the questions are issue-based rather than news- based. Therefore, the right approach to preparation is to prepare issues, rather than just reading news. Taking this into account, our website www.iasbaba.com will cover current affairs focusing more on ‘issues’ on a daily basis. This will help you pick up relevant news items of the day from various national dailies such as The Hindu, Indian Express, Business Standard, LiveMint, Business Line and other important Online sources. Over time, some of these news items will become important issues. UPSC has the knack of picking such issues and asking general opinion based questions. Answering such questions will require general awareness and an overall understanding of the issue. Therefore, we intend to create the right understanding among aspirants – ‘How to cover these issues? This is the 67th edition of IASbaba’s Monthly Magazine. This edition covers all important issues that were in news in the month of DECEMBER 2020 which can be accessed from https://iasbaba.com/current-affairs-for-ias-upsc-exams/ VALUE ADDITIONS FROM IASBABA Must Read and Connecting the dots. Also, we have introduced Prelim and mains focused snippets and Test Your Knowledge (Prelims MCQs based on daily current affairs) which shall guide you for better revision. -

The Queen Kings Ist Die Neue Supergruppe Unter Den

Repertoire _________________________________________________________ Das Queen Kings-Repertoire umfasst über 70 Titel von Queen und Neben- bzw. Soloprojekten der Queen-Musiker. Aus diesem Repertoire von über 4 Stunden wird eine für den Anlass geeignete Spielfolge zusammengestellt. 1. Another one bites the dust 40. Made in heaven 2. A kind of magic 41. March of the black Queen 3. Bicycle Race 42. Millionaire Waltz 4. Breakthru 43. Miracle 5. Barcelona 44. Mr. Bad Guy 6. Bohemian Rhapsody 45. Mustafa 7. Crazy little thing called love 46. Nevermore 8. Dead on time 47. No one but you 9. Death on two legs Live Killers Medley 48. Now I’m here vor Killer Queen 49. Ogre Battle 10. Don’t stop me now 50. One vision 11. Dragon attack 51. Play the game 12. Dreamer’s ball 52. Princes of the universe 13. Fat bottomed girls 53. (Put out the fire) 14. Father to son 54. Radio Ga-Ga 15. Flash / the hero / Flash 55. Sail away sweet sister 16. Friends will be friends 56. Save me 17. Get down, make love 57. Seven seas of rhye halb/komplett 18. Good old-fashioned loverboy 58. Sheer Heart attack 19. Guide me home 59. Somebody to love 20. Hammer to fall 60. Show must go on 21. Heaven for everyone 61. Spread your wings 22. How can I go on 62. Stone cold crazy 23. In my defence 63. Under pressure 24. In the lap of the gods 64. Teo Toriatte 25. Innuendo 65. ’39 26. Invisible Man 66. Tie your mother down 27. Is this the world we created 67. -

Maff Baldwinson Lyrics and Notes

Maff Baldwinson (1970-2017) Lyrics and Notes Draft, April 2018, additions welcome (v2) (c) All Rights Reserved Contents T-shirt printing notes, etc: ................................................................... 3 Loose writings: .................................................................................... 5 Poetry ............................................................................................... 14 Seasons .......................................................................................... 14 Valentine ........................................................................................ 15 Untitled .......................................................................................... 16 Promise .......................................................................................... 17 Dream ............................................................................................ 19 Legacy ............................................................................................ 20 Towers of Spite .............................................................................. 21 Love’s hot fire ................................................................................. 22 Shatter ........................................................................................... 23 Shadow of Doubt .............................................................................. 24 Lyrics ................................................................................................. 26 Untitled, -

The Unexpected Discovery of a Novel Low-Oxygen-Activated Locus for the Anoxic Persistence of Burkholderia Cenocepacia

The ISME Journal (2013), 1–14 OPEN & 2013 International Society for Microbial Ecology All rights reserved 1751-7362/13 www.nature.com/ismej ORIGINAL ARTICLE The unexpected discovery of a novel low-oxygen-activated locus for the anoxic persistence of Burkholderia cenocepacia Andrea M Sass1,2, Crystal Schmerk3, Kirsty Agnoli4, Phillip J Norville1, Leo Eberl4, Miguel A Valvano3,5 and Eshwar Mahenthiralingam1 1Organisms and Environment Division, Cardiff School of Biosciences, Cardiff University, Cardiff, Wales, UK; 2Laboratorium voor Farmaceutische Microbiologie, Universiteit Gent, Gent, Belgium; 3Centre for Human Immunology, Department of Microbiology and Immunology, University of Western Ontario, London, Ontario, Canada; 4Department of Microbiology, Institute of Plant Biology, University of Zu¨rich, Zu¨rich, Switzerland and 5Centre for Infection and Immunity, Queen’s University of Belfast, Belfast, Ireland, UK Burkholderia cenocepacia is a Gram-negative aerobic bacterium that belongs to a group of opportunistic pathogens displaying diverse environmental and pathogenic lifestyles. B. cenocepa- cia is known for its ability to cause lung infections in people with cystic fibrosis and it possesses a large 8 Mb multireplicon genome encoding a wide array of pathogenicity and fitness genes. Transcriptomic profiling across nine growth conditions was performed to identify the global gene expression changes made when B. cenocepacia changes niches from an environmental lifestyle to infection. In comparison to exponential growth, the results demonstrated that B. cenocepacia changes expression of over one-quarter of its genome during conditions of growth arrest, stationary phase and surprisingly, under reduced oxygen concentrations (6% instead of 20.9% normal atmospheric conditions). Multiple virulence factors are upregulated during these growth arrest conditions. -

An Interview with Larry Maxey

AN INTERVIEW WITH LARRY MAXEY Interviewer: Jewell Willhite Oral History Project Endacott Society University of Kansas 1 LARRY MAXEY B.M., “With Honor,” Michigan State University, 1959- Public School Music M.M., Music Literature and Performance, Eastman School of Music, 1960 D.M.A., Performance and Pedagogy, Eastman School of Music, 1968 Service at the University of Kansas First hired at the University of Kansas, 1970 Assistant professor of Clarinet, 1970-1975 Associate Professor of Clarinet, 1975-1980 Professor of Clarinet, 1980-2007 2 AN INTERVIEW WITH LARY MAXEY Interviewer: Jewell Willhite Q: I am speaking with Larry Maxey, who retired as professor of clarinet at the University of Kansas in 2007. We are in Lawrence, Kansas, on December 17, 2007. Where were you born and in what year? A: Michigan City, Indiana, in 1937. Q: What were your parents’ names? A: My father was Charles Sheldon Maxey. He was named after Charles Sheldon, who was the author of What Would Jesus Do? He was at a church in Topeka, although my grandmother, who lived in Indiana, had only heard of him. My mother was Bernice Frey Maxey. Q: My mother’s name was Bernice also. A: Not a very common name. Q: What was their educational background? A: They both had bachelors and masters degrees, and my mother had a nursing degree. She went on to accumulate a lot of graduate hours over the years and eventually ended up with a masters degree in education as well. My father had a master’s. He taught in high school for his entire life. -

PDF of Listening Into Others

LISTENING INTO OTHERS: AN ETHNOGRAPHIC EXPLORATION IN GOVINDPURI TRIPTA CHANDOLA A SERIES OF READERS PUBLISHED BY THE INSTITUTE OF NETWORK CULTURES ISSUE NO.: 36 LISTENING INTO OTHERS: AN ETHNOGRAPHIC EXPLORATION IN GOVINDPURI TRIPTA CHANDOLA 2 THEORY ON DEMAND Theory on Demand #36 Listening into Others: An Ethnographic Exploration in Govindpuri Tripta Chandola Editing: Geert Lovink and Sepp Eckenhaussen Supervision of previous versions: Dr. Jo Tacchi and Dr. Christy Collis Production: Sepp Eckenhaussen Cover design: Katja van Stiphout Publisher: Institute of Network Cultures, Amsterdam, 2020 ISBN 978-94-92302-63-2 Contact Institute of Network Cultures Phone: +31 20 5951865 Email: [email protected] Web: http://www.networkcultures.org This publication is available through various print on demand services. EPUB and PDF editions are freely downloadable from our website: http://networkcultures.org/publications/. This publication is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial- NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0) LISTENING INTO OTHERS: AN ETHNOGRAPHIC EXPLORATION IN GOVINDPURI 3 4 THEORY ON DEMAND CONTENTS PREFACE: FOR BITIYA 6 HOW TO USE THE BOOK 8 FACT SHEET 13 1. IN SEARCH OF THE NEVER-LOST SLUMS: ETHNOGRAPHY OF AN ETHNOGRAPHER 31 2. LISTENING: AN ETHNOGRAPHIC EXPLORATION 45 3. AN ‘OBSCENE’ CALLING EMOTIONALITY IN/OF MARGINALIZED SPACES: A LISTENING OF/INTO ‘ABUSIVE’ WOMEN IN GOVINDPURI 61 4. THE SUBALTERN AS A POLITICAL ‘VOYEUR’? 75 5. COLLABORATIVE LISTENING: ON PRODUCING A RADIO DOCUMENTARY IN THE GOVINDPURI SLUMS - WITH TOM RICE 92 6. I WAIL, THEREFORE I AM 100 7. SONIC SELFIES: EQUALIZING THE ENCOUNTER WITH THE OTHER - IN CONVERSATION WITH JODI DEAN AND GEERT LOVINK 108 8. -

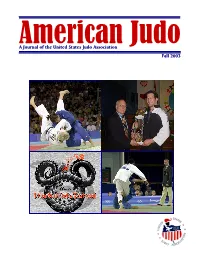

Fall 2003 2 Table of Contents

American Judo A Journal of the United States Judo Association Fall 2003 2 Table of Contents Message from Jim Bregman: Progress Through Outreach James S. Bregman.............................................................................................................5 James S. Bregman CEO Profiles Ed Szrejter......................................................................................................................11 Michael L. Szrejter George Harris................................................................................................................12 President Thomas A. Layon Committee Reports Vice President and Electronic Services National Corporate Tom Reiff .......................................................................................................................15 Counsel 2003 USJA National Symposium Hope Kennedy.................................................................................................................16 James R. Webb Treasurer Technical Notes Eugene S. Fodor Tani Otoshi.....................................................................................................................10 Secretary Basic Choke Defense ..................................................................................................12 Kote Gaeshi Variants .................................................................................................14 Board of Directors USJA Directory .................................................................................................................39 -

Excerpts from the Japan Country Reader

Excerpts from the Japan Country Reader (The complete Reader, more than 1300 pages in length, is available for purchase by contacting [email protected].) JAPAN COUNTRY READER TABLE O CONTENTS on Carroll Bliss, Jr. 1924-1926 Commercial Attach*, Tokyo Cecil B. ,yon 1933 Third Secretary, Tokyo .a/ 0aldo Bishop 1931-1932 ,anguage Training, Tokyo 1932 3ice Consul, Osaka 1938-1941 Political Officer, Tokyo 7lrich A. Straus 1936-1940 Childhood, Japan 1946-1910 8-2 Intelligence Officer, 7nited States .ilitary, Japan .arshall 8reen 1939-1941 Secretary to Ambassador, Tokyo 1942 Japanese ,anguage School, Berkeley, California Niles 0. Bond 1940-1942 Consular Officer, Yokohama Robert A. Fearey 1941-1942 Private Secretary to the 7.S. Ambassador, Tokyo Cliff Forster 1941-1943 Japanese Internment, Philippines Ray .arshall 1941-1946 Naval Occupying Forces, Japan Christopher A. Phillips 1941-1946 7.S. Army = Staff of 8eneral .acArthur, Tokyo Eileen R. onovan 1941-1948 Education Officer, Civil Information and Education, Tokyo 1948-1910 Japan-Korea esk Officer, 0ashington, C Abraham .. Sirkin 1946-1948 Chief of News ivision, 8eneral .acArthurAs BeadCuarters, Tokyo Boward .eyers 1946-1949 ,egal Assistant to 8eneral 0illoughby, Tokyo Benry 8osho 1946-1910 Japan esk, 7SIS, 0ashington, C 0illiam E. Butchinson 1946-1911 Staff of 8eneral .acArthur, Tokyo 1912-1914 Information Officer, 7SIS, Tokyo John R. ODBrien 1946-1948 Press Analyst, Civil Information and Education, Japan 1948-1911 Public Affairs Information Officer, 7SIS, Tokyo Kathryn Clark-Bourne 1942-1910 .ilitary Intelligence, Tokyo Richard A. Ericson, Jr. 1942-1910 Consular Officer, Yokohama 1910-1912 Economic Officer, Tokyo 1913 Japanese ,anguage Training, Tokyo 1914-1918 Economic Officer, Tokyo Richard B.