Mercury Orchestra Channing Yu, Music Director

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Journal81-1.Pdf

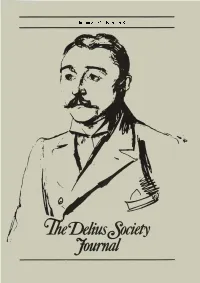

January 1984, Number 81 The Delius Society Journal The Delius Society Journal-_._- January 1984, Number 818l The Delius Society Full Membership £8.00f,8.00 per year Students £5.0095.00 Subscription to Libraries (Journal only) £6.00f,6.00 per year USA and Canada US $17.00 per year President Eric Fenby OBE, Hon DMus,D Mus, Hon DLitt,D Litt, Hon RAM Vice Presidents The Rt Hon Lord Boothby KBE, LLD Felix Aprahamian Hon RCO Roland Gibson M Sc, Ph D (Founder Member) Sir Charles Groves CBE Stanford Robinson OBE, ARCM (Hon), Hon CSM Meredith Davies CBE, MA, BMus,B Mus, FRCM, Hon RAM Norman Del Mar CBE, Hon DMusD Mus YemonVernon Handley MA, FRCM·,FRCM, D Univ (Surrey) Chairman RBR B Meadows 5 Westbourne House, Mount Park Road, Harrow, Middlesex Treasurer Peter Lyons 160 Wishing Tree Road, St. Leonards-on-Sea, East Sussex Secretary Miss Diane Eastwood 28 Emscote Street South, Bell Hall, Halifax, Yorkshire Tel: (0422) 5053750537 Editor Stephen Lloyd 41 Marlborough Road, Luton, Bedfordshire LU3 lEFIEF Tel: Luton (0582)(0582\ 2007520075 2 Contents Editorial . .33 lamesJamesFarrar: Poet, Airman and Delian by Christopher PalmerPalmer. .4 LeslieLeslieHewardbyLyndonJenkinsHeward by Lyndon lenkins .....1313 Fennimore and Gerda at the Edinburgh Festival by Gordon LovgreenIovgreen. .1616 Correspondence .....212] ForthcomingForthcomingEventsEvents ...2121 Acknowledgements The cover illustration is an early sketch of Delius by Edvard Munch reproduced by kind permission of the Curator of the Munch Museum, Oslo. The two photographic plates in this issue have been financed by a legacy to the Delius Society from the late Robert Aickman. ISSN 0306 0373 3 Editorial Perhaps the most keenly anticipated event to have occurred within the past three months has been the publication of Lionel Carley's Delius: A Life in Letters 1862-19081862-1908 (Scolar Press, £25). -

NUI MAYNOOTH Ûllscôst La Ttéiîéann Mâ Üuad Charles Villiers Stanford’S Preludes for Piano Op.163 and Op.179: a Musicological Retrospective

NUI MAYNOOTH Ûllscôst la ttÉiîéann Mâ Üuad Charles Villiers Stanford’s Preludes for Piano op.163 and op.179: A Musicological Retrospective (3 Volumes) Volume 1 Adèle Commins Thesis Submitted to the National University of Ireland, Maynooth for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Music National University of Ireland, Maynooth Maynooth Co. Kildare 2012 Head of Department: Professor Fiona M. Palmer Supervisors: Dr Lorraine Byrne Bodley & Dr Patrick F. Devine Acknowledgements I would like to express my appreciation to a number of people who have helped me throughout my doctoral studies. Firstly, I would like to express my gratitude and appreciation to my supervisors and mentors, Dr Lorraine Byrne Bodley and Dr Patrick Devine, for their guidance, insight, advice, criticism and commitment over the course of my doctoral studies. They enabled me to develop my ideas and bring the project to completion. I am grateful to Professor Fiona Palmer and to Professor Gerard Gillen who encouraged and supported my studies during both my undergraduate and postgraduate studies in the Music Department at NUI Maynooth. It was Professor Gillen who introduced me to Stanford and his music, and for this, I am very grateful. I am grateful to the staff in many libraries and archives for assisting me with my many queries and furnishing me with research materials. In particular, the Stanford Collection at the Robinson Library, Newcastle University has been an invaluable resource during this research project and I would like to thank Melanie Wood, Elaine Archbold and Alan Callender and all the staff at the Robinson Library, for all of their help and for granting me access to the vast Stanford collection. -

The Inspiration Behind Compositions for Clarinetist Frederick Thurston

THE INSPIRATION BEHIND COMPOSITIONS FOR CLARINETIST FREDERICK THURSTON Aileen Marie Razey, B.M., M.M. Dissertation Prepared for the Degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS August 201 8 APPROVED: Kimberly Cole Luevano, Major Professor Warren Henry, Committee Member John Scott, Committee Member John Holt, Chair of the Division of Instrumental Studies Benjamin Brand, Director of Graduate Studies in the College of Music John Richmond, Dean of the College of Music Victor Prybutok, Dean of the Toulouse Graduate School Razey, Aileen Marie. The Inspiration behind Compositions for Clarinetist Frederick Thurston. Doctor of Musical Arts (Performance), August 2018, 86 pp., references, 51 titles. Frederick Thurston was a prominent British clarinet performer and teacher in the first half of the 20th century. Due to the brevity of his life and the impact of two world wars, Thurston’s legacy is often overlooked among clarinetists in the United States. Thurston’s playing inspired 19 composers to write 22 solo and chamber works for him, none of which he personally commissioned. The purpose of this document is to provide a comprehensive biography of Thurston’s career as clarinet performer and teacher with a complete bibliography of compositions written for him. With biographical knowledge and access to the few extant recordings of Thurston’s playing, clarinetists may gain a fuller understanding of Thurston’s ideal clarinet sound and musical ideas. These resources are necessary in order to recognize the qualities about his playing that inspired composers to write for him and to perform these works with the composers’ inspiration in mind. Despite the vast list of works written for and dedicated to Thurston, clarinet players in the United States are not familiar with many of these works, and available resources do not include a complete listing. -

CHAN 9859 Front.Qxd 31/8/07 10:04 Am Page 1

CHAN 9859 Front.qxd 31/8/07 10:04 am Page 1 CHAN 9859 CHANDOS CHAN 9859 BOOK.qxd 31/8/07 10:06 am Page 2 Sir Arthur Sullivan (1842–1900) AKG 1 In memoriam 11:28 Overture in C major in C-Dur . ut majeur Andante religioso – Allegro molto Suite from ‘The Tempest’, Op. 1 27:31 2 1 No. 1. Introduction 5:20 Andante con moto – Allegro non troppo ma con fuoco 3 2 No. 4. Prelude to Act III 1:58 Allegro moderato e con grazia 4 3 No. 6. Banquet Dance 4:39 Allegretto grazioso ma non troppo – Andante – Allegretto grazioso 5 4 No. 7. Overture to Act IV 5:00 Allegro assai con brio 6 5 No. 10. Dance of Nymphs and Reapers 4:21 Allegro vivace e con grazia 7 6 No. 11. Prelude to Act V 4:21 Andante – Allegro con fuoco – Andante 8 7 No. 12c. Epilogue 1:42 Andante sostenuto 3 CHAN 9859 BOOK.qxd 31/8/07 10:06 am Page 4 Sir Arthur Sullivan: Symphony in E major ‘Irish’ etc. Symphony in E major ‘Irish’ 36:02 Sir Arthur Sullivan would have been return to London a public performance in E-Dur . mi majeur delighted to know that the comic operas he of the complete music followed at the 9 I Andante – Allegro, ma non troppo vivace 13:21 wrote with W.S. Gilbert retain their hold on Crystal Palace Concert on 5 April 1862 10 II Andante espressivo 7:13 popular affection a hundred years after his under the baton of August Manns. -

Percy Grainger, Frederick Delius and the 1914–1934 American ‘Delius Campaign’

‘The Art-Twins of Our Timestretch’: Percy Grainger, Frederick Delius and the 1914–1934 American ‘Delius Campaign’ Catherine Sarah Kirby Submitted in total fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Master of Music (Musicology) April 2015 Melbourne Conservatorium of Music The University of Melbourne Produced on archival quality paper Abstract This thesis explores Percy Grainger’s promotion of the music of Frederick Delius in the United States of America between his arrival in New York in 1914 and Delius’s death in 1934. Grainger’s ‘Delius campaign’—the title he gave to his work on behalf of Delius— involved lectures, articles, interviews and performances as both a pianist and conductor. Through this, Grainger was responsible for a number of noteworthy American Delius premieres. He also helped to disseminate Delius’s music by his work as a teacher, and through contact with publishers, conductors and the press. In this thesis I will examine this campaign and the critical reception of its resulting performances, and question the extent to which Grainger’s tireless promotion affected the reception of Delius’s music in the USA. To give context to this campaign, Chapter One outlines the relationship, both personal and compositional, between Delius and Grainger. This is done through analysis of their correspondence, as well as much of Grainger’s broader and autobiographical writings. This chapter also considers the relationship between Grainger, Delius and others musicians within their circle, and explores the extent of their influence upon each other. Chapter Two examines in detail the many elements that made up the ‘Delius campaign’. -

Concert & Recital Programs Concert & Recital Programs

Ithaca College Digital Commons @ IC All Concert & Recital Programs Concert & Recital Programs 12-7-2006 Concert: Ithaca College Concert Band and Ithaca College Symphonic Band, "An Anglo-American Alliance" Ithaca College Concert Band Ithaca College Symphonic Band Elizabeth Peterson John Whitwell Dominic Hartjes Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.ithaca.edu/music_programs Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Ithaca College Concert Band; Ithaca College Symphonic Band; Peterson, Elizabeth; Whitwell, John; and Hartjes, Dominic, "Concert: Ithaca College Concert Band and Ithaca College Symphonic Band, "An Anglo-American Alliance"" (2006). All Concert & Recital Programs. 1197. http://digitalcommons.ithaca.edu/music_programs/1197 This Program is brought to you for free and open access by the Concert & Recital Programs at Digital Commons @ IC. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Concert & Recital Programs by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ IC. ITHACA COLLEGE SCHOOL OF MUSIC ITHACA COLLEGE CONCERT BAND Mark Fonder, conductor John Whitwell, Colonel Arnald Gabriel 'SO, HDRMU '89 Visiting Wind Conductor Dominic Hartjes, graduate conductor and ITHACA COLLEGE SYMPHONIC BAND Elizabeth Peterson, conductor John Whitwell, Colonel Amald Gabriel 'SO, HDRMU '89 Visiting Wind Conductor "An Anglo-American Alliance" Ford Hall . Thursday, December 7, 2006 8:IS p.m. ITHACA ITHACA COLLEGE CONCERT BAND Mark Fonder, conductor Overture Saturnalia (1992) Malcolm Binney (b. 1945) Dominic Hartjes, graduate conductor Cotillon (1938) Arthur Benjamin A Suite of Dance Tunes (1893-1960) Trans. by Silvester Introduction and LordHereford's Delight Daphne's Delight Marlborough's Victory Love's Triumph Jigg It E Foot The Charmer Nymph Divine Tattler Argyle First Suite in E-Flat, op. -

Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Season 77, 1957-1958, Subscription

*l'\ fr^j BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA FOUNDED IN 1881 BY HENRY LEE HIGGINSON 24 G> X will MIIHIi H tf SEVENTY-SEVENTH SEASON 1957-1958 BAYARD TUCEERMAN. JR. ARTHUR J. ANDERSON ROBERT T. FORREST JULIUS F. HALLER ARTHUR J. ANDERSON, JR. HERBERT 8. TUCEERMAN J. DEANE SOMERVILLE It takes only seconds for accidents to occur that damage or destroy property. It takes only a few minutes to develop a complete insurance program that will give you proper coverages in adequate amounts. It might be well for you to spend a little time with us helping to see that in the event of a loss you will find yourself protected with insurance. WHAT TIME to ask for help? Any time! Now! CHARLES H. WATKINS & CO. RICHARD P. NYQUIST in association with OBRION, RUSSELL & CO. Insurance of Every Description 108 Water Street Boston 6, Mast. LA fayette 3-5700 SEVENTY-SEVENTH SEASON, 1957-1958 Boston Symphony Orchestra CHARLES MUNCH, Music Director Richard Burgin, Associate Conductor CONCERT BULLETIN with historical and descriptive notes by John N. Burk Copyright, 1958, by Boston Symphony Orchestra, Inc. The TRUSTEES of the BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA, Inc. Henry B. Cabot President Jacob J. Kaplan Vice-President Richard C. Paine Treasurer Talcott M. Banks Michael T. Kelleher Theodore P. Ferris Henry A. Laughlin Alvan T. Fuller John T. Noonan Francis W. Hatch Palfrey Perkins Harold D. Hodgkinson Charles H. Stockton C. D. Jackson Raymond S. Wilkins E. Morton Jennings, Jr. Oliver Wolcott TRUSTEES EMERITUS Philip R. Allen M. A. DeWolfe Howe N. Penrose Hallowell Lewis Perry Edward A. Taft Thomas D. -

Beethoven's Fourth Symphony: Comparative Analysis of Recorded Performances, Pp

BEETHOVEN’S FOURTH SYMPHONY: RECEPTION, AESTHETICS, PERFORMANCE HISTORY A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School Of Cornell University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Mark Christopher Ferraguto August 2012 © 2012 Mark Christopher Ferraguto BEETHOVEN’S FOURTH SYMPHONY: RECEPTION, AESTHETICS, PERFORMANCE HISTORY Mark Christopher Ferraguto, PhD Cornell University 2012 Despite its established place in the orchestral repertory, Beethoven’s Symphony No. 4 in B-flat, op. 60, has long challenged critics. Lacking titles and other extramusical signifiers, it posed a problem for nineteenth-century critics espousing programmatic modes of analysis; more recently, its aesthetic has been viewed as incongruent with that of the “heroic style,” the paradigm most strongly associated with Beethoven’s voice as a composer. Applying various methodologies, this study argues for a more complex view of the symphony’s aesthetic and cultural significance. Chapter I surveys the reception of the Fourth from its premiere to the present day, arguing that the symphony’s modern reputation emerged as a result of later nineteenth-century readings and misreadings. While the Fourth had a profound impact on Schumann, Berlioz, and Mendelssohn, it elicited more conflicted responses—including aporia and disavowal—from critics ranging from A. B. Marx to J. W. N. Sullivan and beyond. Recent scholarship on previously neglected works and genres has opened up new perspectives on Beethoven’s music, allowing for a fresh appreciation of the Fourth. Haydn’s legacy in 1805–6 provides the background for Chapter II, a study of Beethoven’s engagement with the Haydn–Mozart tradition. -

British and Commonwealth Concertos from the Nineteenth Century to the Present

BRITISH AND COMMONWEALTH CONCERTOS FROM THE NINETEENTH CENTURY TO THE PRESENT A Discography of CDs & LPs Prepared by Michael Herman Composers I-P JOHN IRELAND (1879-1962) Born in Bowdon, Cheshire. He studied at the Royal College of Music with Stanford and simultaneously worked as a professional organist. He continued his career as an organist after graduation and also held a teaching position at the Royal College. Being also an excellent pianist he composed a lot of solo works for this instrument but in addition to the Piano Concerto he is best known for his for his orchestral pieces, especially the London Overture, and several choral works. Piano Concerto in E flat major (1930) Mark Bebbington (piano)/David Curti/Orchestra of the Swan ( + Bax: Piano Concertino) SOMM 093 (2009) Colin Horsley (piano)/Basil Cameron/Royal Philharmonic Orchestra EMI BRITISH COMPOSERS 352279-2 (2 CDs) (2006) (original LP release: HMV CLP1182) (1958) Eileen Joyce (piano)/Sir Adrian Boult/London Philharmonic Orchestra (rec. 1949) ( + The Forgotten Rite and These Things Shall Be) LONDON PHILHARMONIC ORCHESTRA LPO 0041 (2009) Eileen Joyce (piano)/Leslie Heward/Hallé Orchestra (rec. 1942) ( + Moeran: Symphony in G minor) DUTTON LABORATORIES CDBP 9807 (2011) (original LP release: HMV TREASURY EM290462-3 {2 LPs}) (1985) Piers Lane (piano)/David Lloyd-Jones/Ulster Orchestra ( + Legend and Delius: Piano Concerto) HYPERION CDA67296 (2006) John Lenehan (piano)/John Wilson/Royal Liverpool Philharmonic Orchestra ( + Legend, First Rhapsody, Pastoral, Indian Summer, A Sea Idyll and Three Dances) NAXOS 8572598 (2011) MusicWeb International Updated: August 2020 British & Commonwealth Concertos I-P Eric Parkin (piano)/Sir Adrian Boult/London Philharmonic Orchestra ( + These Things Shall Be, Legend, Satyricon Overture and 2 Symphonic Studies) LYRITA SRCD.241 (2007) (original LP release: LYRITA SRCS.36 (1968) Eric Parkin (piano)/Bryden Thomson/London Philharmonic Orchestra ( + Legend and Mai-Dun) CHANDOS CHAN 8461 (1986) Kathryn Stott (piano)/Sir Andrew Davis/BBC Symphony Orchestra (rec. -

Billy Budd Composer Biography: Benjamin Britten

Billy Budd Composer Biography: Benjamin Britten Britten was born, by happy coincidence, on St. Cecilia's Day, at the family home in Lowestoft, Suffolk, England. His father was a dentist. He was the youngest of four children, with a brother, Robert (1907), and two sisters, Barbara (1902) and Beth (1909). He was educated locally, and studied, first, piano, and then, later, viola, from private teachers. He began to compose as early as 1919, and after about 1922, composed steadily until his death. At a concert in 1927, conducted by composer Frank Bridge, he met Bridge, later showed him several of his compositions, and ultimately Bridge took him on as a private pupil. After two years at Gresham's School in Holt, Norfolk, he entered the Royal College of Music in London (1930) where he studied composition with John Ireland and piano with Arthur Benjamin. During his stay at the RCM he won several prizes for his compositions. He completed a choral work, A Boy was Born, in 1933; at a rehearsal for a broadcast performance of the work by the BBC Singers, he met tenor Peter Pears, the beginning of a lifelong personal and professional relationship. (Many of Britten's solo songs, choral and operatic works feature the tenor voice, and Pears was the designated soloist at many of their premieres.) From about 1935 until the beginning of World War II, Britten did a great deal of composing for the GPO Film Unit, for BBC Radio, and for small, usually left-wing, theater groups in London. During this period he met and worked frequently with the poet W. -

The Australian Symphony of the 1950S: a Preliminary Survey

The Australian Symphony of the 1950s: A Preliminary survey Introduction The period of the 1950s was arguably Australia’s ‘Symphonic decade’. In 1951 alone, 36 Australian symphonies were entries in the Commonwealth Jubilee Symphony Competition. This music is largely unknown today. Except for six of the Alfred Hill symphonies, arguably the least representative of Australian composition during the 1950s and a short Sinfonietta- like piece by Peggy Glanville-Hicks, the Sinfonia da Pacifica, no Australian symphony of the period is in any current recording catalogue, or published in score. No major study or thesis to date has explored the Australian symphony output of the 1950s. Is the neglect of this large repertory justified? Writing in 1972, James Murdoch made the following assessment of some of the major Australian composers of the 1950s. Generally speaking, the works of the older composers have been underestimated. Hughes, Hanson, Le Gallienne and Sutherland, were composing works at least equal to those of the minor English composers who established sizeable reputations in their own country.i This positive evaluation highlights the present state of neglect towards Australian music of the period. Whereas recent recordings and scores of many second-ranking British and American composers from the period 1930-1960 exist, almost none of the larger works of Australians Robert Hughes, Raymond Hanson, Dorian Le Gallienne and their contemporaries are heard today. This essay has three aims: firstly, to show how extensive symphonic composition was in Australia during the 1950s, secondly to highlight the achievement of the main figures in this movement and thirdly, to advocate the restoration and revival of this repertory. -

UPBEAT AUTUMN 2018 CONTENTS WELCOME 4 NEWS the Latest News and Activities from to UPBEAT the Royal College of Music

UPBEAT AUTUMN 2018 You will only make NEWS FROM an impression if your INSIDE THE ROYAL COLLEGE OF MUSIC heart and soul are free to interpret the music you IN THIS ISSUE want to perform. DAME SARAH CONNOLLY BATTLE SOUNDS: COMPOSERS Sarah Connolly ON THE FRONT LINE HIGHLIGHTS IN THE LOCKED ROOM & THE LIGHTHOUSE This summer acclaimed theatre director Stephen Unwin joined forces with Michael Rosewell to lead a talented RCM cast in two thrilling operas by Peter Maxwell Davies and Huw Watkins. Photos: Chris Chistodoulou Front cover: image courtesy of Christopher Pledger 2 UPBEAT AUTUMN 2018 CONTENTS WELCOME 4 NEWS The latest news and activities from TO UPBEAT the Royal College of Music In this issue, we celebrate some of the talented vocal and 9 operatic work that takes place at the Royal College of Music – IN THE SPOTLIGHT RCM Costume Supervisor both on and off the Britten Theatre stage. Jools Osborne On page 12, hear from one of the most celebrated voices in classical music today: alumna Dame Sarah Connolly. The mezzo-soprano’s new release pays homage both to 120 years of both British 10 BATTLE SOUNDS song and her own RCM connection, with each of the 29 tracks written by RCM composers on the front line a composer who either taught or studied at the College. Read about her incredible musical journey, from soaking up opera in the RCM Library, to singing Rule Britannia at the Last Night of the BBC Proms. 12 Our opera theme continues with a backstage look at one of the most visually DAME SARAH CONNOLLY impressive aspects of any production: costume.