Post-Tsunami Changes in the Knowledge and Practices of the Nicobarese

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Recommendations on Improving Telecom Services in Andaman

Telecom Regulatory Authority of India Recommendations on Improving Telecom Services in Andaman & Nicobar Islands and Lakshadweep 22 nd July, 2014 Mahanagar Doorsanchar Bhawan Jawahar Lal Nehru Marg, New Delhi – 110002 CONTENTS CHAPTER-I: INTRODUCTION 1 CHAPTER- II: METHODOLOGY FOLLOWED FOR THE ASSESSMENT OF THE TELECOM INFRASTRUCTURE REQUIRED 10 CHAPTER- III: TELECOM PLAN FOR ANDAMAN & NICOBAR ISLANDS 36 CHAPTER- IV: COMPREHENSIVE TELECOM PLAN FOR LAKSHADWEEP 60 CHAPTER- V: SUPPORTING POLICY INITIATIVES 74 CHAPTER- VI: SUMMARY OF RECOMMENDATIONS 84 ANNEXURE 1.1 88 ANNEXURE 1.2 90 ANNEXURE 2.1 95 ANNEXURE 2.2 98 ANNEXURE 3.1 100 ANNEXURE 3.2 101 ANNEXURE 5.1 106 ANNEXURE 5.2 110 ANNEXURE 5.3 113 ABBREVIATIONS USED 115 i CHAPTER-I: INTRODUCTION Reference from Department of Telecommunication 1.1. Over the last decade, the growth of telecom infrastructure has become closely linked with the economic development of a country, especially the development of rural and remote areas. The challenge for developing countries is to ensure that telecommunication services, and the resulting benefits of economic, social and cultural development which these services promote, are extended effectively and efficiently throughout the rural and remote areas - those areas which in the past have often been disadvantaged, with few or no telecommunication services. 1.2. The Role of telecommunication connectivity is vital for delivery of e- Governance services at the doorstep of citizens, promotion of tourism in an area, educational development in terms of tele-education, in health care in terms of telemedicine facilities. In respect of safety and security too telecommunication connectivity plays a vital role. -

November 17-2

Tuesday 2 Daily Telegrams November 17, 2020 GOVT. PRIMARY SCHOOL No. TN/DB/PHED/2020/1277 27 SUBHASGRAM - 2 HALDER PARA, SARDAR TIKREY DO OFFICE OF THE EXECUTIVE ENGINEER NSV, SUBHASHGRAM GOVT. PRIMARY SCHOOL PUBLIC HEALTH ENGINEERING DIVISION 28 SUBHASGRAM - 3 DAS PARA, DAKHAIYA PARA DO A.P.W.D., PORT BLAIR NSV, SUBHASHGRAM th SCHOOL TIKREY, SUB CENTER Prothrapur, dated the 13 November 2020. COMMUNITY HALL, 29 KHUDIRAMPUR AREA, STEEL BRIDGE, AAGA DO KHUDIRAMPUR TENDER NOTICE NALLAH, DAM AREA (F) The Executive Engineer, PHED, APWD, Prothrapur invites on behalf of President of India, online Item Rate e- BANGLADESH QUARTER, MEDICAL RAMAKRISHNAG GOVT. PRIMARY SCHOOL tenders (in form of CPWD-8) from the vehicle owners / approved and eligible contractors of APWD and Non APWD 30 COLONY AREA, SAJJAL PARA, R K DO RAM - 1 RAMKRISHNAGRAM Contractors irrespective of their enlistment subject to the condition that they have experience of having successfully GRAM HOUSE SITE completed similar nature of work in terms of cost in any of the government department in A&N Islands and they should GOVT. PRIMARY SCHOOL RAMAKRISHNAG BAIRAGI PARA, MALO PARA, 31 VV PITH, DO not have any adverse remarks for following work RAM - 2 PAHAR KANDA NIT No. Earnest RAMKRISHNAGRAM Sl. Estimated cost Time of Name of work Money RAMAKRISHNAG COMMUNITY HALL, NEAR MAGAR NALLAH WATER TANK No. put to Tender Completion 32 DO Deposit RAM - 3 VKV, RAMKRISHNAGRAM AREA, POLICE TIKREY, DAS PARA VIDYASAGARPAL GOVT. PRIMARY SCHOOL SAITAN TIKRI, PANDEY BAZAAR, 1 NIT NO- R&M of different water pump sets under 33 DO 15/DB/ PHED/ E & M Sub Division attached with EE LI VS PALLY HELIPAD AREA GOVT. -

On the Andaman and Nicobar Islands, Bay of Bengal

Herpetology Notes, volume 13: 631-637 (2020) (published online on 05 August 2020) An update to species distribution records of geckos (Reptilia: Squamata: Gekkonidae) on the Andaman and Nicobar Islands, Bay of Bengal Ashwini V. Mohan1,2,* The Andaman and Nicobar Islands are rifted arc-raft of 2004, and human-mediated transport can introduce continental islands (Ali, 2018). Andaman and Nicobar additional species to these islands (Chandramouli, 2015). Islands together form the largest archipelago in the In this study, I provide an update for the occurrence Bay of Bengal and a high proportion of terrestrial and distribution of species in the family Gekkonidae herpetofauna on these islands are endemic (Das, 1999). (geckos) on the Andaman and Nicobar Islands. Although often lumped together, the Andamans and Nicobars are distinct from each other in their floral Materials and Methods and faunal species communities and are geographically Teams consisted of between 2–4 members and we separated by the 10° Channel. Several studies have conducted opportunistic visual encounter surveys in shed light on distribution, density and taxonomic accessible forested and human-modified areas, both aspects of terrestrial herpetofauna on these islands during daylight hours and post-sunset. These surveys (e.g., Das, 1999; Chandramouli, 2016; Harikrishnan were carried out specifically for geckos between and Vasudevan, 2018), assessed genetic diversity November 2016 and May 2017, this period overlapped across island populations (Mohan et al., 2018), studied with the north-east monsoon and summer seasons in the impacts of introduced species on herpetofauna these islands. A total of 16 islands in the Andaman and and biodiversity (e.g., Mohanty et al., 2016a, 2019), Nicobar archipelagos (Fig. -

International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources

INTERNATIONAL UNION FOR CONSERVATION OF NATURE AND NATURAL RESOURCES Report on Land Use in the ANDAMAN AND NICOBAR ISLANDS by D.N. McVean IUCN CONSULTANT Library CH - 1196 Gland With Financial Assistance from The Government of India and The United Nations Environmental Programme Morges, Switzerland Jwte, 1976 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction ••••••••••••••••••••••ct•••• .. •••••·••••••••••11:e•••••••••• 1 SuDID8.ry ••••••••••••••••••••••••••• 4 ••••••• ,. fl •• fl " M .............. 6 •• a • • 1 ENVIRONMENTAL Il!PACT ASSESSMENT ....... " .. " .......................... 2 Effect of de.forestation on climate • " • ll ............................ 2 Accelerated soil erosion ........... ....... ... .. .... ................ 3 Water supplies, perennial and seasonal ... " ....................... 5 Forestry ···•~41~••••11•••••···········••t-•••····················· 7 Agriculture and settlement ••••••••••....••••• , • • • • . • • • • • • • • • • • • • 9 Plantation agriculture ••••11•••·••!:ilf'• '!lr ••························· 11 Other development 12 ··············-~r.o••··················-····· CONSERVATION .......................... ., ...... ,_ ................... 14 Terrestrial habitats •••• S • e • I • IJ ... I ••• S e 4 I' ••• e ••• • ••••••••• I' ••••• 14 Marine habitats .............. ....... II. ....................... 17 Indigenous tribes • ' .. e • • llJo 1' • + "' • e .. + • • • • • • • • • ' ' • Ill- 4' .. t • • ... II 4 41 • •• • • 18 COMMEN'.i:S ON PREVIOUS REPORTS ...... ,.••••••••• ,.,. •••••••••••••••••••••• 41. 19 RECOMMENDATIONS -

Chapter 2 Introduction to the Geography and Geomorphology Of

Downloaded from http://mem.lyellcollection.org/ by guest on February 7, 2017 Chapter 2 Introduction to the geography and geomorphology of the Andaman–Nicobar Islands P. C. BANDOPADHYAY1* & A. CARTER2 1Department of Geology, University of Calcutta, 35 Ballygunge Circular Road, Kolkata-700019, India 2Department of Earth & Planetary Sciences, Birkbeck, University of London, London, UK *Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: The geography and the geomorphology of the Andaman–Nicobar accretionary ridge (islands) is extremely varied, recording a complex interaction between tectonics, climate, eustacy and surface uplift and weathering processes. This chapter outlines the principal geographical features of this diverse group of islands. Gold Open Access: This article is published under the terms of the CC-BY 3.0 license The Andaman–Nicobar archipelago is the emergent part of a administrative headquarters of the Nicobar Group. Other long ridge which extends from the Arakan–Yoma ranges of islands of importance are Katchal, Camorta, Nancowry, Till- western Myanmar (Burma) in the north to Sumatra in the angchong, Chowra, Little Nicobar and Great Nicobar. The lat- south. To the east the archipelago is flanked by the Andaman ter is the largest covering 1045 km2. Indira Point on the south Sea and to the west by the Bay of Bengal (Fig. 1.1). A coast of Great Nicobar Island, named after the honorable Prime c. 160 km wide submarine channel running parallel to the Minister Smt Indira Gandhi of India, lies 147 km from the 108 N latitude between Car Nicobar and Little Andaman northern tip of Sumatra and is India’s southernmost point. -

RETICULATED PYTHON Malayopython Reticulatus (SCHNEIDER 1801) : RESCUE, RECOVERY and RECENT SIGHTINGS from GREAT NICOBAR ISLAND-A CONSERVATION APPROACH

ECOPRINT 22: 50-55, 2015 ISSN 1024-8668 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.3126/eco.v22i0.15470 Ecological Society (ECOS), Nepal www.nepjol.info/index.php/eco; www.ecosnepal.com RETICULATED PYTHON Malayopython reticulatus (SCHNEIDER 1801) : RESCUE, RECOVERY AND RECENT SIGHTINGS FROM GREAT NICOBAR ISLAND-A CONSERVATION APPROACH S. Rajeshkumar 1*, C. Raghunathan 1 and Kailash Chandra 2 1Zoological Survey of India, Andaman and Nicobar Regional Centre Port Blair-744 102, Andaman and Nicobar Islands, India 2Zoological Survey of India, M-Block, New Alipore, Kolkatta-700 053, India *Email: [email protected] ABSTRACT Previously the Reticulated python was recorded by few researchers from Nicobar Islands In 2006, four individuals were observed, but there was no more information added in their literature about sightings in Great Nicobar Island. Pythons were considered as an uncommon and rare encountered species in India also to the Nicobar Islands. Pythons considered relatively rare appearance to have declined due to frequent eradication by habitat destruction On 25 th August 2013, first individual of reticulated python was caught by the local people at Govind Nagar (Lat: 07° 00.074' N, Long: 093° 54.128' E, Altitude at 49.4 meter) in Great Nicobar Island The second one was rescued on 31 st August 2013 in the same area by the local people. Both the recovered individuals were appeared as juvenile. Investigations on population census of this threatened species and their habitat have been felt from the present incidences. Key words : .................................... INTRODUCTION as Malayopython reticulatus (Schneider 1801). Snakes are perhaps one of the most difficult Python is locally (in Nicobarese) called as vertebrate groups to survey (Groombridge and ‘Yammai’ or ‘Tulanth’ (Chandi 2006) and Luxmoore 1991). -

Omobranchus with Descriptions of Three New Species and Notes on Other Species of the Tribe Omobranchini

Revision of the Blenniid Fish Genus Omobranchus with Descriptions of Three New Species and Notes on Other Species of the Tribe Omobranchini VICTOR G. SPRINGER and MARTIN F. GOMON SMITHSONIAN CONTRIBUTIONS TO ZOOLOGY • NUMBER 177 SERIAL PUBLICATIONS OF THE SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION The emphasis upon publications as a means of diffusing knowledge was expressed by the first Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution. In his formal plan for the Insti- tution, Joseph Henry articulated a program that included the following statement: "It is proposed to publish a series of reports, giving an account of the new discoveries in science, and of the changes made from year to year in all branches of knowledge." This keynote of basic research has been adhered to over the years in the issuance of thousands of titles in serial publications under the Smithsonian imprint, com- mencing with Smithsonian Contributions to Knowledge in 1848 and continuing with the following active series: Smithsonian Annals of Flight Smithsonian Contributions to Anthropology Smithsonian Contributions to Astrophysics Smithsonian Contributions to Botany Smithsonian Contributions to the Earth Sciences Smithsonian Contributions to Paleobiology Smithsonian Contributions to Zoology Smithsonian Studies in History and Technology In these series, the Institution publishes original articles and monographs dealing with the research and collections of its several museums and offices and of professional colleagues at other institutions of learning. These papers report newly acquired facts, synoptic interpretations of data, or original theory in specialized fields. These pub- lications are distributed by mailing lists to libraries, laboratories, and other interested institutions and specialists throughout the world. Individual copies may be obtained from the Smithsonian Institution Press as long as stocks are available. -

NITI Aayog's Project for Great Nicobar Island

NITI Aayog’s Project for Great Nicobar Island drishtiias.com/printpdf/niti-aayog-s-project-for-great-nicobar-island Why in News Recently, the Environment Appraisal Committee which flagged concerns over the project has now ‘recommended’ it ‘for grant of terms of reference’ for Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) studies. In August, 2020 the Prime Minister had declared that the Andaman and Nicobar islands will be developed as a "maritime and startup hub". Key Points About the Project: The proposal includes an international container trans-shipment terminal, a greenfield international airport, a power plant and a township complex spread over 166 sq. km. (mainly pristine coastal systems and tropical forests). It is estimated to cost Rs. 75,000 crore. 1/3 Issues with Project: Lack of details on seismic and tsunami hazards, freshwater requirement details, and details of the impact on the Giant Leatherback turtle. No details of the trees to be felled—a number that could run into millions since 130 sq. km. of the project area has some of the finest tropical forests in India. A number of additional issues include about Galathea Bay, the site of the port and the centrepiece of the NITI Aayog proposal. Galathea Bay is an iconic nesting site in India of the enigmatic Giant Leatherback, the world’s largest marine turtle—borne out by surveys done over three decades. Ecological surveys in the last few years have reported a number of new species, many restricted to just the Galathea region. These include the critically endangered Nicobar shrew, the Great Nicobar crake, the Nicobar frog, the Nicobar cat snake, a new skink (Lipinia sp), a new lizard (Dibamus sp,) and a snake of the Lycodon sp that is yet to be described. -

October 2017 Smith's Giant Gecko (Gekko Smithii) from the Great

Project Update: October 2017 Smith's giant gecko (Gekko smithii) from the Great Nicobar Island Acknowledgements: I thank the Andaman and Nicobar Environmental Team (ANET) for facilitating field work for this project for a duration of 6 months, Department of Environment and Forests, Andaman and Nicobar Islands for providing permission to carry out this study and collect tissues for molecular laboratory work (Permit No.: CWLW/WL/134(A)/517), Andaman and Nicobar Administration for providing permission to carryout field work in Tribal Reserve Areas and the Police Department, A&N Islands for providing logistical support in remote locations. Objectives: 1. To identify diversity in gecko species and populations distributed on the Andaman and Nicobar islands 2. To recognise factors governing patterns of genetic diversity across space (dispersal ability, barriers of dispersal, isolation-by-distance, human mediated dispersal). 3. To assess evolutionary relationships of the endemic and human commensal lineages of geckos from the Andaman and Nicobar Islands and deduce bio- geographical affinities of these Islands. 4. To prioritise islands and species for conservation. Tasks, timeline and status: Task Timeline Status Permits for the study October 2016-January Complete Field data collection in the October2017 2016-May 2017 Complete A&N Islands Molecular laboratory work May 2017-August 2017 In progress Morphological data July-August 2017 In progress Preparinganalysis publications August- November 2017 In progress Designing and printing October 2017 Yet to begin education material Project final report November 2017 Yet to begin Summary of field data collection: We began field work on October 26th 2016 and completed this on May 3rd, 2017. -

Impact Assessment and Economic Benefits of Weather and Marine Services

Impact Assessment and Economic Benefits of Weather and Marine Services December 2010 National Council of Applied Economic Research (NCAER) Parisila Bhawan, 11, I.P. Estate New Delhi- 110 002, INDIA Tel: +91-11-2337 9861-63 Fax: +91-11-2337 0164 Website: www.ncaer.org copyright@2010 by the National Council of Applied Economic Research, New Delhi – 110 002. Preface The Ministry of Earth Sciences (MoES) was formed in 2006 from a merger of the India Meteorological Department (IMD), the National Centre for Medium Range Weather Forecasting (NCMRWF), the Indian Institute of Tropical Meteorology (IITM), Pune, Earth Risk Evaluation Centre (EREC), and the Department of Ocean Development. The Mission of the MoES is to provide the nation with forecasts of the monsoons and other weather/climate parameters, and information about ocean state, earthquakes, tsunamis and other phenomena related to earth systems through well-integrated programs. These services have significant economic and social benefits that are otherwise very difficult to quantify. The actual and potential benefits to the key stakeholders like individuals, firms, industry sectors and national bodies from state-of-the-art meteorological and related services are substantial and, till today, they are inadequately recognised and insufficiently exploited in India. NCAER was approached by the MoES to carry out a comprehensive study to understand the perspectives of the main stakeholders on the weather and marine services and estimate the economic and social benefits of these services provided by the MoES. However the MoES provides numerous services and the number of beneficiaries is large. This study has restricted to the main stakeholders, such as farmers and fishermen. -

Annual Report 2018-19

GOVENMENT OF INDIA MINISTRY OF HOME AFFAIRS ANNUAL REPORT 2018-19 CONTENTS Chapter - 1 1-5 Mandate and Organisational Structure of the Ministry of Home Affairs Chapter - 2 6-33 Internal Security Chapter - 3 34-50 Border Management Chapter - 4 51-55 Centre-State Relations Chapter - 5 56-63 Crime Scenario in the Country Chapter - 6 64-69 Human Rights and National Integration Chapter - 7 70-109 Union Territories Chapter - 8 110-147 POLICE FORCES Chapter - 9 148-169 Other Police Organizations and Institutions Chapter - 10 170-199 Disaster Management Chapter - 11 200-211 International Cooperation Chapter - 12 212-231 Major Initiatives and Schemes Chapter - 13 232-249 Foreigners, Freedom Fighters’ Pension and Rehabilitation Chapter - 14 250-261 Women Safety Chapter - 15 262-274 Registrar General and Census Commissioner, India (RG&CCI) Chapter - 16 275-287 Miscellaneous Issues Annexures 289-337 (I-XXIII) Annual Report 2018-19 Annual Report 2018-19 Chapter - 1 Mandate and Organisational Structure of The Ministry of Home Affairs 1.1 The Ministry of Home Affairs (MHA) Organisational Chart has also been given discharges multifarious responsibilities, at Annexure-II. the important among them being - internal 1.3 The list of existing Divisions of the security, border management, Centre- Ministry of Home Affairs indicating major State relations, administration of Union areas of their responsibility are as below: Territories, management of Central Armed Police Forces, disaster management, etc. Administration Division Though in terms of Entries 1 and 2 of List II – ‘State List’ – in the Seventh Schedule 1.4 The Administration Division is responsible for handling all administrative to the Constitution of India, ‘public order’ matters and allocation of work among and ‘police’ are the responsibilities of various Divisions of the Ministry. -

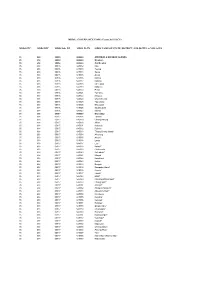

MDDS STC MDDS DTC MDDS Sub DT MDDS PLCN MDDS NAME of STATE, DISTRICT, SUB-DISTTS. & VILLAGES MDDS E-GOVERNANCE CODE (Census

MDDS e-GOVERNANCE CODE (Census 2011 PLCN) MDDS STC MDDS DTC MDDS Sub_DT MDDS PLCN MDDS NAME OF STATE, DISTRICT, SUB-DISTTS. & VILLAGES 35 000 00000 000000 ANDAMAN & NICOBAR ISLANDS 35 638 00000 000000 Nicobars 35 638 05916 000000 Car Nicobar 35 638 05916 645012 Mus 35 638 05916 645013 Teetop 35 638 05916 645014 Sawai 35 638 05916 645015 Arong 35 638 05916 645016 Kimois 35 638 05916 645017 Kakana 35 638 05916 645018 IAF Camp 35 638 05916 645019 Malacca 35 638 05916 645020 Perka 35 638 05916 645021 Tamaloo 35 638 05916 645022 Kinyuka 35 638 05916 645023 Chuckchucha 35 638 05916 645024 Tapoiming 35 638 05916 645025 Big Lapati 35 638 05916 645026 Small Lapati 35 638 05916 645027 Kinmai 35 638 05917 000000 Nancowry 35 638 05917 645028 Tahaila 35 638 05917 645029 Chongkamong 35 638 05917 645030 Alhiat 35 638 05917 645031 Kuitasuk 35 638 05917 645032 Raihion 35 638 05917 645033 Tillang Chong Island* 35 638 05917 645034 Aloorang 35 638 05917 645035 Aloora* 35 638 05917 645036 Enam 35 638 05917 645037 Luxi 35 638 05917 645038 Kalara* 35 638 05917 645039 Chukmachi 35 638 05917 645040 Safedbalu* 35 638 05917 645041 Minyuk 35 638 05917 645042 Kanahinot 35 638 05917 645043 Kalasi 35 638 05917 645044 Bengali 35 638 05917 645045 Bompoka Island* 35 638 05917 645046 Jhoola* 35 638 05917 645047 Jansin* 35 638 05917 645048 Hitlat* 35 638 05917 645049 Mavatapis/Maratapia* 35 638 05917 645050 Chonghipoh* 35 638 05917 645051 Sanaya* 35 638 05917 645052 Alkaipoh/Alkripoh* 35 638 05917 645053 Alhitoth/Alhiloth* 35 638 05917 645054 Katahuwa* 35 638 05917 645055