Earthquakes Mechanics and Effects

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Temporal and Spatial Evolution Analysis of Earthquake Events in California and Nevada Based on Spatial Statistics

International Journal of Geo-Information Article Temporal and Spatial Evolution Analysis of Earthquake Events in California and Nevada Based on Spatial Statistics Weifeng Shan 1,2 , Zhihao Wang 2, Yuntian Teng 1,* and Maofa Wang 3 1 Institute of Geophysics, China Earthquake Administration, Beijing 100081, China; [email protected] 2 School of Emergency Management, Institute of Disaster Prevention, Langfang 065201, China; [email protected] 3 School of Computer and Information Security, Guilin University of Electronic Science and Technology, Guilin 541004, China; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: Studying the temporal and spatial evolution trends in earthquakes in an area is beneficial for determining the earthquake risk of the area so that local governments can make the correct decisions for disaster prevention and reduction. In this paper, we propose a new method for analyzing the temporal and spatial evolution trends in earthquakes based on earthquakes of magnitude 3.0 or above from 1980 to 2019 in California and Nevada. The experiment’s results show that (1) the frequency of earthquake events of magnitude 4.5 or above present a relatively regular change trend of decreasing–rising in this area; (2) by using the weighted average center method to analyze the spatial concentration of earthquake events of magnitude 3.0 or above in this region, we find that the weighted average center of the earthquake events in this area shows a conch-type movement law, where it moves closer to the center from all sides; (3) the direction of the spatial distribution of earthquake events in this area shows a NW–SE pattern when the standard deviational ellipse (SDE) Citation: Shan, W.; Wang, Z.; Teng, method is used, which is basically consistent with the direction of the San Andreas Fault Zone across Y.; Wang, M. -

2010 1. How Do Earthquakes Occur?

CE Earthquake Review- 2010 1. How do earthquakes occur? They occur by tectonic plates moving past each other. 2. What are the three different plate boundaries? Transform, convergent, divergent. 3. What are some effects of earthquakes? Mountains can be formed, volcanoes can be formed, and trenches can be formed. 4. What is a convergent plate boundary? When two plates collide. 5. What is a divergent plate boundary? When two plates separate. 6. What is a transform plate boundary? When two plates slide past each other. 7. How are mountains formed? It’s created by a convergent plate boundary. 8. What are the layers of the earth? Crust, mantle, outer core, and inner core. 9. How did the scientists know Pangaea existed? Fossils, rocks, climate, and the fit of the continents. 10. How do scientists know about the layers of the earth? Earthquakes waves travel to seismograph stations through the inner earth. 11. What causes convection currents? Uneven heating 12. What causes earthquakes? Convection currents in the earth’s mantle move tectonic plates and build up pressure that is suddenly released, causing earthquakes. 13. What is the difference between an S-wave and a P-wave? P-wave is faster (Push and Pull), S-wave is slower (Side to Side) 14. What causes a rift valley? A divergent plate boundary spreading apart and filling with magma. 15. What is a subduction zone? A convergent plate boundary where one plate is pushed under another. 16. What is the inner core made of and how do we know? Iron and nickel because the earth has a magnetic field. -

Earthquake Basics

RESEARCH DELAWARE State of Delaware DELAWARE GEOLOGICAL SURVEY SERVICEGEOLOGICAL Robert R. Jordan, State Geologist SURVEY EXPLORATION SPECIAL PUBLICATION NO. 23 EARTHQUAKE BASICS by Stefanie J. Baxter University of Delaware Newark, Delaware 2000 CONTENTS Page INTRODUCTION . 1 EARTHQUAKE BASICS What Causes Earthquakes? . 1 Seismic Waves . 2 Faults . 4 Measuring Earthquakes-Magnitude and Intensity . 4 Recording Earthquakes . 8 REFERENCES CITED . 10 GLOSSARY . 11 ILLUSTRATIONS Figure Page 1. Major tectonic plates, midocean ridges, and trenches . 2 2. Ground motion near the surface of the earth produced by four types of earthquake waves . 3 3. Three primary types of fault motion . 4 4. Duration Magnitude for Delaware Geological Survey seismic station (NED) located near Newark, Delaware . 6 5. Contoured intensity map of felt reports received after February 1973 earthquake in northern Delaware . 8 6. Model of earliest seismoscope invented in 132 A. D. 9 TABLES Table Page 1. The 15 largest earthquakes in the United States . 5 2. The 15 largest earthquakes in the contiguous United States . 5 3. Comparison of magnitude, intensity, and energy equivalent for earthquakes . 7 NOTE: Definition of words in italics are found in the glossary. EARTHQUAKE BASICS Stefanie J. Baxter INTRODUCTION Every year approximately 3,000,000 earthquakes occur worldwide. Ninety eight percent of them are less than a mag- nitude 3. Fewer than 20 earthquakes occur each year, on average, that are considered major (magnitude 7.0 – 7.9) or great (magnitude 8 and greater). During the 1990s the United States experienced approximately 28,000 earthquakes; nine were con- sidered major and occurred in either Alaska or California (Source: U.S. -

Earthquakes Read Chapters 2.1, 2.10.1-3 in KK&V Homework 1!

Lecture 4: Earthquakes Read Chapters 2.1, 2.10.1-3 in KK&V Homework 1! (due next Thursday) Global distribution of earthquakes (circa 1960) San Francisco Earthquake April 18, 1906 5:12 am Magnitude 8.3 430 km rupture 6 meters of slip Reid, 1910; Byerly & DeNoyer, 1958; Knopoff, 1958; Chinnery, 1964 18 PERRY BYERLY AND JOHN DfiNOYER For these three earthquakes the horizontal displacements occurring at the time of the shock or those due to strain (about to be relieved) just before the shock may be represented by the empirical equation 2M 1 V = COt" ax (1) 7T where the plane of the fault is the yz plane, the z axis pointing down dip and the y axis is horizontal. The xz plane bisects the fault plane. is in direction of the axis is the maxi- The displacement v the y ; M mum value of v. The fit of this equation is the kind of fit to which we are accustomed in seismology as is shown in Figs. 1, 2, 3. 300 250 ZOO SAN FRANCISCO * POINTS EAST OF FAULT o POINTS WEST OF FAULT 100 In the California earthquakes the displacement was almost wholly horizontal; in the Nevada shock there was also considerable vertical displacement. The Earthquake Cycle Coseismic (seconds) Interseismic (102-103 yrs) Geologic - Multiple Earthquakes (103-106 yrs) The Earthquake Cycle Measuring earthquakes: the old way (China, 132 AD) Fundamentally, a seismograph is a simple pendulum. When the ground shakes, the base and frame of the instrument move with it, but inertia keeps the pendulum bob in place. -

Short-Term Foreshocks As Key Information for Mainshock Timing and Rupture: the Mw6.8 25 October 2018 Zakynthos Earthquake, Hellenic Subduction Zone

sensors Article Short-Term Foreshocks as Key Information for Mainshock Timing and Rupture: The Mw6.8 25 October 2018 Zakynthos Earthquake, Hellenic Subduction Zone Gerassimos A. Papadopoulos 1,*, Apostolos Agalos 1 , George Minadakis 2,3, Ioanna Triantafyllou 4 and Pavlos Krassakis 5 1 International Society for the Prevention & Mitigation of Natural Hazards, 10681 Athens, Greece; [email protected] 2 Department of Bioinformatics, The Cyprus Institute of Neurology & Genetics, 6 International Airport Avenue, Nicosia 2370, P.O. Box 23462, Nicosia 1683, Cyprus; [email protected] 3 The Cyprus School of Molecular Medicine, The Cyprus Institute of Neurology & Genetics, 6 International Airport Avenue, Nicosia 2370, P.O. Box 23462, Nicosia 1683, Cyprus 4 Department of Geology & Geoenvironment, National & Kapodistrian University of Athens, 15784 Athens, Greece; [email protected] 5 Centre for Research and Technology, Hellas (CERTH), 52 Egialias Street, 15125 Athens, Greece; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 28 August 2020; Accepted: 30 September 2020; Published: 5 October 2020 Abstract: Significant seismicity anomalies preceded the 25 October 2018 mainshock (Mw = 6.8), NW Hellenic Arc: a transient intermediate-term (~2 yrs) swarm and a short-term (last 6 months) cluster with typical time-size-space foreshock patterns: activity increase, b-value drop, foreshocks move towards mainshock epicenter. The anomalies were identified with both a standard earthquake catalogue and a catalogue relocated with the Non-Linear Location (NLLoc) algorithm. Teleseismic P-waveforms inversion showed oblique-slip rupture with strike 10◦, dip 24◦, length ~70 km, faulting depth ~24 km, velocity 3.2 km/s, duration 18 s, slip 1.8 m within the asperity, seismic moment 26 2.0 10 dyne*cm. -

International Aspects of the History of Earthquake Engineering

International Aspects Of the History of Earthquake Engineering Part I February 12, 2008 Draft Robert Reitherman Executive Director Consortium of Universities for Research in Earthquake Engineering This draft contains Part I: Acknowledgements Chapter 1: Introduction Chapter 2: Japan The planned contents of Part II are chapters 3 through 6 on China, India, Italy, and Turkey. Oakland, California 1 Table of Contents Acknowledgments .......................................................................................................................i Chapter 1 Introduction ................................................................................................................1 “Earthquake Engineering”.......................................................................................................1 “International” ........................................................................................................................3 Why Study the History of Earthquake Engineering?................................................................4 Earthquake Engineering History is Fascinating .......................................................................5 A Reminder of the Value of Thinking .....................................................................................6 Engineering Can Be Narrow, History is Broad ........................................................................6 Respect: Giving Credit Where Credit Is Due ..........................................................................7 The Importance -

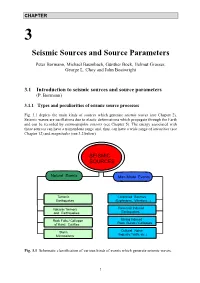

Seismic Sources and Source Parameters

CHAPTER 3 Seismic Sources and Source Parameters Peter Bormann, Michael Baumbach, Günther Bock, Helmut Grosser, George L. Choy and John Boatwright 3.1 Introduction to seismic sources and source parameters (P. Bormann) 3.1.1 Types and peculiarities of seismic source processes Fig. 3.1 depicts the main kinds of sources which generate seismic waves (see Chapter 2). Seismic waves are oscillations due to elastic deformations which propagate through the Earth and can be recorded by seismographic sensors (see Chapter 5) . The energy associated with these sources can have a tremendous range and, thus, can have a wide range of intensities (see Chapter 12) and magnitudes (see 3.2 below) . SEISMIC SOURCES Natural Events Man-Made Events Tectonic Controlled Sources Earthquakes ( Explosions, Vibrators...) Volcanic Tremors Reservoir Induced and Earthquakes Earthquakes Rock Falls / Collapse Mining Induced of Karst Cavities Rock Bursts / Collapses Cultural Noise Storm Microseisms ( Industry, Traffic etc.) Fig. 3.1 Schematic classification of various kinds of events which generate seismic waves. 1 3. Seismic Sources and Source Parameters 3.1.1.1 Tectonic earthquakes Tectonic earthquakes are caused when the brittle part of the Earth’s crust is subjected to stress that exceeds its breaking strength. Sudden rupture will occur, mostly along pre-existing faults or sometimes along newly formed faults. Rocks on each side of the rupture "snap" into a new position. For very large earthquakes, the length of the ruptured zone may be as much as 1000 km and the slip along the fault can reach several meters. Laboratory experiments show that homogeneous consolidated rocks under pressure and temperature conditions at the Earth's surface will fracture at a volume strain on the order of 10 -2 - 10 -3 (i.e., about 0.1 % to 1% volume change) depending upon their porosity. -

Study of Ethylenediaminetetraacetic Acid

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Covenant University Repository Journal of Advances in Biological and Basic Research 01[01] 2015 www.asdpub.com/index.php/jabbr ISSN-XXXX-XXXX (Online) Review Article Earthquake: A terrifying of all natural phenomena T.A. Adagunodo1,2* and L.A. Sunmonu1,2 1Department of Pure and Applied Physics, Ladoke Akintola University of Technology, P.M.B. 4000, Ogbomoso, Nigeria. 2Geophysics/Physics of the Solid Earth Section, P/A Physics, LAUTECH, Ogbomoso, Nigeria. *Corresponding Author Abstract Earthquake is the passage of vibrations (seismic wave) that spread out in all T.A. Adagunodo directions from the source of the disturbance when rocks are suddenly disturbed. An Department of Pure and Applied Physics, earthquake is caused by sudden slip on a fault which itself described by epicenter, focus, Ladoke Akintola University of Technology, focal depth, after shock, fore shock, magnitude of earthquake, intensity of an earthquake P.M.B. 4000, Ogbomoso, Nigeria. and intensity. Elastic rebound model is a useful guide to how an earthquake may occur. E-mail: [email protected] This manuscript reviews the rock responses to stress and the relationship between faults and earthquake. It also reviews the types of earthquake, earthquake seismology, Keywords: differences between seismic refraction and reflection as well as basic Physics behind an Earthquake, Faults, Seismic Reflection, earthquake phenomenon. Seismic Refraction, Seismology, Stress, Volcanoes. 1. Introduction few millimeters to thousands of kilometers. Most faults produced An earthquake is caused by a sudden slip on a fault. repeated displacements over geologic time. -

Correlations of Seismicity Patterns in Southern California with Surface Heat Flow Data by Bogdan Enescu,* Sebastian Hainzl, and Yehuda Ben-Zion

Bulletin of the Seismological Society of America, Vol. 99, No. 6, pp. 3114–3123, December 2009, doi: 10.1785/0120080038 Correlations of Seismicity Patterns in Southern California with Surface Heat Flow Data by Bogdan Enescu,* Sebastian Hainzl, and Yehuda Ben-Zion Abstract We investigate the relations between properties of seismicity patterns in southern California and the surface heat flow using a relocated earthquake catalog. We first search for earthquake sequences that are well separated in time and space from other seismicity and then determine the epidemic type aftershock sequence (ETAS) model parameters for the sequences with a sufficient number of events. We focus on the productivity parameter α of the ETAS model that quantifies the relative effi- ciency of an earthquake with magnitude M to produce aftershocks. By stacking sequences with relatively small and relatively large α values separately, we observed clear differences between the two groups. Sequences with a smaller α have a relatively large number of foreshocks and relatively small number of aftershocks. In contrast, more typical sequences with larger α have relatively few foreshocks and larger number of aftershocks. The stacked premainshock activity for the more typical latter sequences has a clear increase in the day before the occurrence of the main event. The spatial distribution of the α values correlates well with the surface heat flow: areas of high heat flow are characterized by relatively small α, indicating that in such regions the swarm-type earthquake activity is more common. Our results are compat- ible with a damage rheology model that predicts swarm-type seismic activity in areas with relatively high heat flow and more typical foreshock–mainshock–aftershock sequences in regions with normal or low surface heat flow. -

I. Earthquakes A. General Features 1.Vibration of Earth Produced by the Rapid Release of Energy 2.Associated with Movements Along Faults A

I. Earthquakes A. General features 1.Vibration of Earth produced by the rapid release of energy 2.Associated with movements along faults a. Explained by the plate tectonics theory b. Mechanism for earthquakes was first explained by H. Reid B. Early 1900s 1.Rocks "spring back" a. Phenomena called elastic rebound b. Vibrations (earthquakes) occur as rock elastically returns to its original shape 2.Often preceded by foreshocks 3.Often followed by aftershocks 4. Fault creep II. Earthquake waves A. Study of earthquake waves is called seismology B. Earthquake recording instrument (seismograph) 1.Records movement of Earth 2.Record is called a seismogram C. Types of earthquake waves 1.Body waves travel through Earth—two types a. Primary (P) waves 1) Push-pull (compressional) motion 2) Travel through a) Solids b) Liquids c) Gases b. Greatest velocity of all earthquake waves 2.Secondary (S) waves a. "Shake" motion, side-to-side b. Travel only through solids c. Slower velocity than P waves 3.Surface waves— a. travel on Earth’s surface b. often extremely damaging c. Complex motion d. Slowest velocity of all waves III. Locating an earthquake A. Focus – the place within Earth where earthquake waves originate B. Epicenter 1.Point on the surface, directly above the focus 2.Located using the difference in the arrival times between P and S wave recordings, which are related to distance a. Three station recordings are needed to locate an epicenter Earthquakes 2006 Nov 7 Page 1 of 3 b. Circle equal to the epicenter distance is drawn around each station c. -

Source Duration Scales with Magnitude Differently for Earthquakes on the San Andreas Fault and on Secondary Faults in Parkfield, California by Rebecca M

Bulletin of the Seismological Society of America, Vol. 99, No. 4, pp. 2323–2334, August 2009, doi: 10.1785/0120080216 Ⓔ Source Duration Scales with Magnitude Differently for Earthquakes on the San Andreas Fault and on Secondary Faults in Parkfield, California by Rebecca M. Harrington and Emily E. Brodsky Abstract We used a comparison of source time function pulse widths to show that a group of earthquakes on the San Andreas fault near Parkfield have a constant duration over a magnitude range of 1.4–3.7. Earthquakes on secondary faults have an increase in duration with magnitude, which is the expected relationship for the usual observation of constant stress drop. The constant duration suggests that fault area is the same regardless of magnitude and that variations in stress drop are due entirely to variations in slip. Calculated stress-drop values on secondary faults range from 0.31 to 14 MPa, and stress-drop values on the San Andreas fault range from 0.18 to 63 MPa. The observation of constant duration on the San Andreas fault is consistent with a model of a locked asperity in a creeping fault. The differences in durations between the events on the San Andreas fault and on secondary faults suggest that earthquakes on the San Andreas fault are inherently different. We speculate that faults with more cumulative displacement have earthquakes that may rupture differently. Furthermore, the differences in source properties between the two populations might be explained by differences in fault surface roughness. Online Material: Station subsets used to evaluate cross-fault seismic velocity contrasts. -

Essential Questions

Topic/Theme: Earthquakes NYS ILS Standards: Essential Questions: 1. What causes earthquakes? 2. How are earthquakes measured? 3. How can scientists predict earthquakes and avoid hazards? 4. What measures are scientists taking to prevent earthquake damage? Performance Indicators: • Analysis of earthquake wave data (vibrational disturbances) leads to the conclusion that there are layers within Earth. These layers in the crust, mantle, outer core, and inner core have distinct properties. • Plates may collide, move apart, or slide past one another. Most volcanic activity and mountain building occur at the boundaries of these plates, often resulting in earthquakes. • Folded, tilted, faulted, and displaced rock layers suggest past crustal movement. Essential Knowledge and Skills: • Stresses on Earth’s crust produce shearing, compression and tension in rock. • Faulting and folding of the crust forms mountains and other features. • Seismic waves carry an earthquake’s energy through the Earth. • There are two types of seismic waves: P-waves and S-waves. • There are three types of earthquake scales: moment magnitude, Mercalli and Richter. • Earthquakes can cause damage to buildings and other structures. • New buildings can be designed to withstand minor earthquakes. • For people who live in earthquake-prone areas, it’s important to have an earthquake safety plan. Classroom/Assessment Ideas: • Stress activity (clay or Play Doh) • Fault activity (fault blocks) • Seismic waves demo (Slinky) • Finding an Epicenter Lab (CCR 1,3 CCW 3) • Earthquake Safety Plan poster (CCR 9,6 CCW 1,2,3) • Earthquake Resistant Building Project (CCR 2,4,9 CCW 7,8,9) • Earthquake Hazards Lab (CCR 1,7 CCW 3) Vocabulary: earthquake stress shearing tension compression fault strike-slip normal reverse hanging wall footwall folds anticline syncline focus epicenter seismic waves P-waves S-waves surface waves seismograph Mercalli scale Richter scale moment magnitude scale liquefaction tsunamis aftershock base-isolated building .