The Whole Force by Design: Optimising Defence to Meet Future Challenges

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The German Army, Vimy Ridge and the Elastic Defence in Depth in 1917

Journal of Military and Strategic VOLUME 18, ISSUE 2 Studies “Lessons learned” in WWI: The German Army, Vimy Ridge and the Elastic Defence in Depth in 1917 Christian Stachelbeck The Battle of Arras in the spring of 1917 marked the beginning of the major allied offensives on the western front. The attack by the British 1st Army (Horne) and 3rd Army (Allenby) was intended to divert attention from the French main offensive under General Robert Nivelle at the Chemin des Dames (Nivelle Offensive). 1 The French commander-in-chief wanted to force the decisive breakthrough in the west. Between 9 and 12 April, the British had succeeded in penetrating the front across a width of 18 kilometres and advancing around six kilometres, while the Canadian corps (Byng), deployed for the first time in closed formation, seized the ridge near Vimy, which had been fiercely contested since late 1914.2 The success was paid for with the bloody loss of 1 On the German side, the battles at Arras between 2 April and 20 May 1917 were officially referred to as Schlacht bei Arras (Battle of Arras). In Canada, the term Battle of Vimy Ridge is commonly used for the initial phase of the battle. The seizure of Vimy ridge was a central objective of the offensive and was intended to secure the protection of the northern flank of the 3rd Army. 2 For detailed information on this, see: Jack Sheldon, The German Army on Vimy Ridge 1914-1917 (Barnsley: Pen&Sword Military, 2008), p. 8. Sheldon's book, however, is basically a largely indiscriminate succession of extensive quotes from regimental histories, diaries and force files from the Bavarian War Archive (Kriegsarchiv) in Munich. -

Zero Day Exploits and National Readiness for Cyber-Warfare

Nigerian Journal of Technology (NIJOTECH) Vol. 36, No. 4, October 2017, pp. 1174 – 1183 Copyright© Faculty of Engineering, University of Nigeria, Nsukka, Print ISSN: 0331-8443, Electronic ISSN: 2467-8821 www.nijotech.com http://dx.doi.org/10.4314/njt.v36i4.26 ZERO DAY EXPLOITS AND NATIONAL READINESS FOR CYBER-WARFARE A. E. Ibor* DEPT. OF COMPUTER SCIENCE, CROSS RIVER UNIVERSITY OF TECHNOLOGY, CALABAR, CROSS RIVER STATE NIGERIA E-mail address: [email protected] ABSTRACT A zero day vulnerability is an unknown exploit that divulges security flaws in software before such a flaw is publicly reported or announced. But how should a nation react to a zero day? This question is a concern for most national governments, and one that requires a systematic approach for its resolution. The securities of critical infrastructure of nations and states have been severally violated by cybercriminals. Nation-state espionage and the possible disruption and circumvention of the security of critical networks has been on the increase. Most of these violations are possible through detectable operational bypasses, which are rather ignored by security administrators. One common instance of a detectable operational bypass is the non-application of periodic security updates and upgrades from software and hardware vendors. Every software is not necessarily in its final state, and the application of periodic updates allow for the patching of vulnerable systems, making them to be secure enough to withstand an exploit. To have control over the security of critical national assets, a nation must be “cyber-ready” through the proper management of vulnerabilities and the deployment of the rightful technology in the cyberspace for hunting, detecting and preventing cyber-attacks and espionage. -

Ministerial Appointments, July 2018

Ministerial appointments, July 2018 Department Secretary of State Permanent Secretary PM The Rt Hon Theresa May MP The Rt Hon Brandon Lewis MP James Cleverly MP (Deputy Gavin Barwell (Chief of Staff) (Party Chairman) Party Chairman) Cabinet Office The Rt Hon David Lidington The Rt Hon Andrea Leadsom The Rt Hon Brandon Lewis MP Oliver Dowden CBE MP Chloe Smith MP (Parliamentary John Manzoni (Chief Exec of Sir Jeremy Heywood CBE MP (Chancellor of the MP (Lord President of the (Minister without portolio) (Parliamentary Secretary, Secretary, Minister for the the Civil Service) (Head of the Civil Duchy of Lancaster and Council and Leader of the HoC) Minister for Implementation) Constitution) Service, Cabinet Minister for the Cabinet Office) Secretary) Treasury (HMT) The Rt Hon Philip Hammond The Rt Hon Elizabeth Truss MP The Rt Hon Mel Stride MP John Glen MP (Economic Robert Jenrick MP (Exchequer Tom Scholar MP (Chief Secretary to the (Financial Secretary to the Secretary to the Treasury) Secretary to the Treasury) Treasury) Treasury) Ministry of Housing, The Rt Hon James Brokenshire Kit Malthouse MP (Minister of Jake Berry MP (Parliamentary Rishi Sunak (Parliamentary Heather Wheeler MP Lord Bourne of Aberystwyth Nigel Adams (Parliamentary Melanie Dawes CB Communities & Local MP State for Housing) Under Secretary of State and Under Secretary of State, (Parliamentary Under Secretary (Parliamentary Under Secretary Under Secretary of State) Government (MHCLG) Minister for the Northern Minister for Local Government) of State, Minister for Housing of State and Minister for Faith) Powerhouse and Local Growth) and Homelessness) Jointly with Wales Office) Business, Energy & Industrial The Rt Hon Greg Clark MP The Rt Hon Claire Perry MP Sam Gyimah (Minister of State Andrew Griffiths MP Richard Harrington MP The Rt Hon Lord Henley Alex Chisholm Strategy (BEIS) (Minister of State for Energy for Universities, Science, (Parliamentary Under Secretary (Parliamentary Under Secretary (Parliamentary Under Secretary and Clean Growth) Research and Innovation). -

Kaunas University of Technology Urban Planning

KAUNAS UNIVERSITY OF TECHNOLOGY CIVIL ENGINEERING AND ARCHITECTURE FACULTY Ana Petriashvili URBAN PLANNING AND DESIGN FOR TERRORISM RESILIENT CITIES Master degree final project Supervisor Assoc. prof. dr. Irina Matijosaitiene Co-supervisor Johan Jacob Marija De Wachter KAUNAS 2017 1 KAUNAS UNIVERSITY OF TECHNOLOGY CIVIL ENGINEERING AND ARCHITECTURE FACULTY URBAN PLANNING AND DESIGN FOR TERRORISM RESILIENT CITIES Master degree final project Architecture (621K10001) Supervisor Assoc. prof. dr. Irina Matijosaitiene Co-supervisor Johan Jacob Marija De Wachter Reviewer Assoc. prof. dr. Martynas Marozas Project made by Ana Petriashvili KAUNAS 2017 2 ANNOTATION The lack of researches, concentrating on identifying urban features that can be associated with target selection by terrorists, determined thesis overriding question and goal, identify environmental security design elements, as well as spatial urban structures that can possible influence choice of places for terror attacks. To accomplish main goal, some prerequisite goals have been taken into account. Initially, a brief history of terrorism and anti-terrorism design with number of examples and cases have been analyzed and assessed, where some sophisticated security design principles have been highlighted. For humanizing ant-terrorism design elements, crime prevention strategies have been explored, ending with a basic principle of urban and civic design. Second Chapter of a thesis, researches environmental design factors and spatial urban structures that may influence the choice of places for terror attacks. Findings have reviled the chance of terror attack is high when ‘site has a direct access to the main street’; when ‘there are multiple entrances and exits to and from the site’; when ‘site is well-used’; when ‘public and private activities are separated’; when ‘many same functional buildings are redistributed in a surrounding area’; when ‘site has a direct access to the city center’. -

Army Medic~Orps

J R Army Med Corps: first published as 10.1136/jramc-78-02-01 on 1 February 1942. Downloaded from VOL. LXXVIII. FEBRUARY, 1942. No. 2. Authors are alone responsible for the statements _' ("...8<:8. 0 4~~ mad. ODd ... opinioruo ........... in ,'oh "P~ :!t ~({!1gr ~o~'1I)!;$ ~"- .~ ~ ~ 1,/~~~' Journal .~ • ~~40~ ~ of the ~~' O~ _ Royal Army Medic~orps. Original Communications. 2021 by guest. Protected copyright. " BLITZKRIEG." AN APPRECIATION. By BRI(!ADIER E. M. COWELL, C.B., CB.E., D.S.a., T.D. THIS is the title of a small book written by F. O. Miksche and recently published by Faber and Faber Ltd., London. The author, an officer of the Regular Army :of the Czechoslovak Republic for twelve years, served with distinction with the Republican forces in the late War in Spain. The book is described by Tom Wintringham in his introduction as "a Conti nental, a European\ essay on Tactics." LieutenantMiksche writes with a sound knowledge of Germal1 tactics and a practical experience of Total War. He is in a position to be able to describe' tJ.()t only the plans for attack' on the new lines exploited by the http://militaryhealth.bmj.com/ Germans with their ,armoured and motorized forces but also the methods to be adopted in defence in depth, as employed so brilliantly by our gallant Russian allies to-day. ' All medical officers in a Field Force will perform their duties with success 'proportional to their knowl~dge'oftactics. Whether it be the Regimental Medical Officer or the Director of Medical Services, m~dical arral~gements wiIH,,\iluilless'the tictical situation be studied, understood and appreciated tram a ptactical angle. -

Preventing and Countering Youth Radicalisation in the EU

DIRECTORATE GENERAL FOR INTERNAL POLICIES POLICY DEPARTMENT C: CITIZENS' RIGHTS AND CONSTITUTIONAL AFFAIRS CIVIL LIBERTIES, JUSTICE AND HOME AFFAIRS Preventing and countering youth radicalisation in the EU STUDY Abstract Upon request by the LIBE Committee, this study focuses on the question of how to best prevent youth radicalisation in the EU. It evaluates counter-radicalisation policies, both in terms of their efficiency and their broader social and political impact. Building on a conception of radicalisation as a process of escalation, it highlights the need to take into account the relation between individuals, groups and state responses. In this light, it forefronts some of the shortcomings of current policies, such as the difficulties of reporting individuals on the grounds of uncertain assessments of danger and the problem of attributing political grievances to ethnic and religious specificities. Finally, the study highlights the ambiguous nature of pro-active administrative practices and exceptional counter-terrorism legislation and their potentially damaging effects in terms of fundamental rights. PE 509.977 EN DOCUMENT REQUESTED BY THE COMMITTEE ON CIVIL LIBERTIES, JUSTICE AND HOME AFFAIRS (LIBE) AUTHORS Professor Didier BIGO (Director, CCLS – Professor at King’s College, United-Kingdom) Dr Laurent BONELLI (Associate researcher, CCLS – Lecturer at the University of Nanterre Paris X, France) Dr Emmanuel-Pierre GUITTET (Associate researcher, CCLS – Lecturer at the University of Manchester, United-Kingdom) Dr Francesco RAGAZZI (Associate researcher, CCLS – Lecturer at the University of Leiden, Netherlands) RESPONSIBLE ADMINISTRATOR Ms Sarah SY Policy Department C - Citizens' Rights and Constitutional Affairs European Parliament B-1047 Brussels E-mail: [email protected] LINGUISTIC VERSIONS Original: EN ABOUT THE EDITOR Policy Departments provide in-house and external expertise to support EP committees and other parliamentary bodies in shaping legislation and exercising democratic scrutiny over EU internal policies. -

CTC Sentinel Welcomes Submissions

OBJECTIVE ·· RELEVANT ·· RIGOROUS || JUNE/JULYMARCH 2019 2018 · VOLUME · VOLUME 12, 11,ISSUE ISSUE 3 6 FEATURE ARTICLE A VIEW FROM THE CT FOXHOLE A VIEW FROM THE CT FOXHOLE TheHezbollah's Jihadi Threat Procurement Channels LTC(R)Vayl S. Bryan Oxford Price toHow theIndonesia group leverages criminal networks and partners with Iran Director, Former Defense Director, Threat KirstenMatthew E. SchulzeLevitt CombatingReduction Terrorism Agency Center FEATURE ARTICLE 1 Hezbollah's Procurement Channels: Leveraging Criminal Networks and Editor in Chief Partnering with Iran Paul Cruickshank Matthew Levitt Managing Editor INTERVIEW Kristina Hummel 10 A View from the CT Foxhole: Vayl S. Oxford, Director, Defense Threat Reduction Agency EDITORIAL BOARD Kristina Hummel Colonel Suzanne Nielsen, Ph.D. ANALYSIS Department Head Dept. of Social Sciences (West Point) 15 Military Interventions, Jihadi Networks, and Terrorist Entrepreneurs: How the Islamic State Terror Wave Rose So High in Europe Brian Dodwell Petter Nesser Director, CTC 22 The Islamic State's Revitalization in Libya and its Post-2016 War of Attrition Lachlan Wilson and Jason Pack Don Rassler Director of Strategic Initiatives, CTC 32 AQIM Pleads for Relevance in Algeria Geoff D. Porter CONTACT Combating Terrorism Center In our cover article, Matthew Levitt examines Hezbollah’s procurement channels, documenting how the group has been leveraging an internation- U.S. Military Academy al network of companies and brokers, including Hezbollah operatives and 607 Cullum Road, Lincoln Hall criminal -

A Look at the European Union's Challenges Through Romania's

The European Union at the Crossroads: A Look at the European Union’s Challenges through Romania’s Lenses A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies and Research In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of Master of Arts in Political Science University of Regina By Lidia Vasilica Costa-Muresan Regina, Saskatchewan March 2018 Copyright 2017: L.V. Costa-Muresan UNIVERSITY OF REGINA FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES AND RESEARCH SUPERVISORY AND EXAMINING COMMITTEE Lidia Vasilica Costa-Muresan, candidate for the degree of Master of Arts in Political Science, has presented a thesis titled, The European Union at the Crossroads: A Look at the European Union’s Challenges through Romania’s Lenses, in an oral examination held on December 4, 2017. The following committee members have found the thesis acceptable in form and content, and that the candidate demonstrated satisfactory knowledge of the subject material. External Examiner: Dr. Bruno Dupeyron, Johnson Shoyama Graduate School Supervisor: Dr. Nilgun Onder, Department of Political Science & International Studies Committee Member: Dr. Yuchao Zhu, Department of Political Science & International Studies Committee Member: Dr. Martin Hewson, Department of Political Science & International Studies Chair of Defense: Dr. Harminder Guliani, Department of Economics Abstract “A crisis does not fall from the sky; political crises are not unforeseeable natural catastrophes, which one stands helpless in the face of. They build gradually, accumulating explosive power piece by piece, and then after years of negligence, they are detonated. The heads of state and government behaved nonchalantly as the crisis mounted; they made no attempt to comprehend the dark that gathered over the European pathways.” (Junker, 2005, para. -

Implementation of Defence in Depth at Nuclear Power Plants

Nuclear Regulation 2016 Implementation of Defence in Depth at Nuclear Power Plants Lessons Learnt from the Fukushima Daiichi Accident NEA Nuclear Regulation Implementation of Defence in Depth at Nuclear Power Plants Lessons Learnt from the Fukushima Daiichi Accident © OECD 2016 NEA No. 7248 NUCLEAR ENERGY AGENCY ORGANISATION FOR ECONOMIC CO-OPERATION AND DEVELOPMENT ORGANISATION FOR ECONOMIC CO-OPERATION AND DEVELOPMENT The OECD is a unique forum where the governments of 34 democracies work together to address the economic, social and environmental challenges of globalisation. The OECD is also at the forefront of efforts to understand and to help governments respond to new developments and concerns, such as corporate governance, the information economy and the challenges of an ageing population. The Organisation provides a setting where governments can compare policy experiences, seek answers to common problems, identify good practice and work to co-ordinate domestic and international policies. The OECD member countries are: Australia, Austria, Belgium, Canada, Chile, the Czech Republic, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Iceland, Ireland, Israel, Italy, Japan, Korea, Luxembourg, Mexico, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, Poland, Portugal, the Slovak Republic, Slovenia, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, Turkey, the United Kingdom and the United States. The European Commission takes part in the work of the OECD. OECD Publishing disseminates widely the results of the Organisation’s statistics gathering and research on economic, social and environmental issues, as well as the conventions, guidelines and standards agreed by its members. This work is published on the responsibility of the OECD Secretary-General. NUCLEAR ENERGY AGENCY The OECD Nuclear Energy Agency (NEA) was established on 1 February 1958. -

EVOLUTION of the FINNISH MILITARY DOCTRINE 1945-1985 Pekka Visuri

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by National Library of Finland DSpace Services FINNISH DEFENCE STUDIES EVOLUTION OF THE FINNISH MILITARY DOCTRINE 1945-1985 Pekka Visuri OCUMENTATION War College Helsinki 1990 Finnish Defence Studies is published under the auspices of the War College, and the contributions reflect the fields of research and teaching of the College. Finnish Defence Studies will occasionally feature documentation on Finnish Security Policy. Views expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily imply endorsement by the War College. Editor: Kalevi Ruhala Editorial Assistant: Matti Hongisto Editorial Board: Chairman Prof. Mikko Viitasalo, War College Dr. Pauli Järvenpää, Ministry of Defence Col. Tauno Nieminen, General Headquarters Dr., Lt.Col. (ret.) Pekka Visuri, Finnish Institute of International Affairs Dr. Matti Vuorio, Scientific Committee for National Defence Published by WAR COLLEGE P.O. Box 266 SF - 00171 Helsinki FINLAND FINNISH DEFENCE STUDIES 1 EVOLUTION OF THE FINNISH MILITARY DOCTRINE 1945-1985 Pekka Visuri DOCUMENTATION War College Helsinki 1990 ISBN 951-25-0522-3 ISSN 0788-5571 © Copyright 1990: War College All rights reserved Valtion painatuskeskus Pasilan VALTIMO Helsinki 1990 CONTENTS INTRODUCTION..................................................................................... 3 Purpose and approach ............................................................................. 3 Theoretical framework ............................................................................ -

The Wilhelm's Battle

The Wilhelm’s battle Prologue Paris, France, March 29 th , 1918, district of Saint Gervais, Good Friday. In the church of the district, some people have met for praying. There are men, women, young and old people. Suddenly, a whistle overwhelms the whisper of the prayers. The faithful become silent, they prick up their ears towards that sinister whistle which is closer and closer… Then, only fire and smoke, flames and dust , blood and screams. Vaults and walls collapse, tons of stones and bricks fall on the faithful. Paris is under fire of a monstrous gun made by the Krupp Factories. In the previous days, some other places of the city had been hit by it. Many inhabitants had already left the city. The Germans are almost at one hundred kilometres from Paris. And they are advancing. A nasty situation. After almost four years of war, Germany was exhausted. Bread was lacking, the infant mortality had doubled, the economy was on its knees, Socialists and Pacifists were adding fuel to the flames, the social riots were increasing. Till that time, on the western front, Germany had stood on defensive , intending – and hoping- to convince the Allies about the impossibility of a victory on the field and to force them to negotiate the peace. The attempts had failed; the Chancellor Theobald Bethman-Hollweg-- a moderate-- had resigned and the power, de facto, had passed into the hands of the militaries. Nasty business when the policy is decided by the militaries. They had imposed the indiscriminate submarine warfare, they were about to impose a new offensive on the western front. -

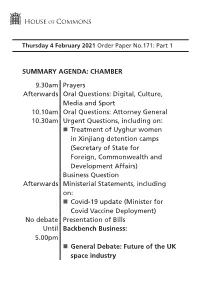

Thursday 4 February 2021 Order Paper No.171: Part 1

Thursday 4 February 2021 Order Paper No.171: Part 1 SUMMARY AGENDA: CHAMBER 9.30am Prayers Afterwards Oral Questions: Digital, Culture, Media and Sport 10.10am Oral Questions: Attorney General 10.30am Urgent Questions, including on: Treatment of Uyghur women in Xinjiang detention camps (Secretary of State for Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Affairs) Business Question Afterwards Ministerial Statements, including on: Covid-19 update (Minister for Covid Vaccine Deployment) No debate Presentation of Bills Until Backbench Business: 5.00pm General Debate: Future of the UK space industry 2 Thursday 4 February 2021 OP No.171: Part 1 General Debate: Towns Fund Until Adjournment Debate: Driving tests 5.30pm or in High Wycombe (Steve Baker) for half an hour Thursday 4 February 2021 OP No.171: Part 1 3 CONTENTS CONTENTS PART 1: BUSINESS TODAY 5 Chamber 8 Written Statements 10 Committees Meeting Today 15 Committee Reports Published Today 16 Announcements 21 Further Information PART 2: FUTURE BUSINESS 26 A. Calendar of Business Notes: Item marked [R] indicates that a member has declared a relevant interest. Thursday 4 February 2021 OP No.171: Part 1 5 BUSINESS TOday: CHAMBER BUSINESS TODAY: CHAMBER Virtual participation in proceedings will commence after Prayers. 9.30am Prayers Followed by QUESTIONS 1. Digital, Culture, Media and Sport 2. Attorney General The call list for Members participating is available on the House of Commons business papers pages. URGENT QUESTIONS AND STATEMENTS Urgent Question: To ask the Secretary of State for Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Affairs, if he will make a statement on the treatment of Uyghur women in Xinjiang detention camps (Nusrat Ghani) 6 Thursday 4 February 2021 OP No.171: Part 1 BUSINESS TOday: CHAMBER Business Question to the Leader of the House Ministerial Statements, including Minister for Covid Vaccine Deployment on covid-19 update The call list for Members participating is available on the House of Commons business papers pages.