The Final Days of Billy the Kid

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Billy the Kid: More Than a Legend

National Park Service White Sands U.S. Department of the Interior White Sands National Monument Billy the Kid: More than a Legend he history of the American Southwest is chock full of legends and stories that truly live up to the epithet of the TWild West. The embellishment of these stories has allowed for the development of numerous movies and books but the true facts of these accounts are more interesting than any tall tale. Yes, the West really was wild! after Tunstall. According to most doubt he and other renowned William Henry McCarthy, accounts, he was shot unarmed characters of the time came across otherwise known as Billy the which was against “the code of the largerst gypsum dunefield in Kid, is a perfect example of how the West.” After Tunstall’s murder, the world as they traveled. Who untamed the now tranquil towns Billy and the Regulators swore knows what evidence of their of New Mexico used to be. It vengeance on Jesse Evans and his passage these ever-shifting dunes was no secret that Billy had a crew. might be hiding. rough past. His mother died of tuberculosis while he was just a As a result of one of the many —Sandra Flickinger, Student-Intern young boy and he had a history of skirmishes, Sheriff William Brady working odd jobs in combination was killed, putting Billy in the hot with a few illegal activities. seat as a murderer and sending him on the run. After many daring The real beginning of Billy’s career escapes, the new sheriff, Pat as an infamous gunman, however, Garrett, was finally successful in began in 1878 after he met a young arresting Billy. -

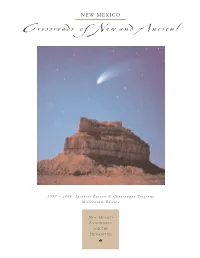

Crossroads of Newand Ancient

NEW MEXICO Crossroads of NewandAncient 1999 – 2000 Speakers Bureau & Chautauqua Programs Millennium Edition N EW M EXICO E NDOWMENT FOR THE H UMANITIES ABOUT THE COVER: AMATEUR PHOTOGRAPHER MARKO KECMAN of Aztec captures the crossroads of ancient and modern in New Mexico with this image of Comet Hale-Bopp over Fajada Butte in Chaco Culture National Historic Park. Kecman wanted to juxtapose the new comet with the butte that was an astronomical observatory in the years 900 – 1200 AD. Fajada (banded) Butte is home to the ancestral Puebloan sun shrine popularly known as “The Sun Dagger” site. The butte is closed to visitors to protect its fragile cultural sites. The clear skies over the Southwest led to discovery of Hale-Bopp on July 22-23, 1995. Alan Hale saw the comet from his driveway in Cloudcroft, New Mexico, and Thomas Bopp saw the comet from the desert near Stanfield, Arizona at about the same time. Marko Kecman: 115 N. Mesa Verde Ave., Aztec, NM, 87410, 505-334-2523 Alan Hale: Southwest Institute for Space Research, 15 E. Spur Rd., Cloudcroft, NM 88317, 505-687-2075 1999-2000 NEW MEXICO ENDOWMENT FOR THE HUMANITIES SPEAKERS BUREAU & CHAUTAUQUA PROGRAMS Welcome to the Millennium Edition of the New Mexico Endowment for the Humanities (NMEH) Resource Center Programming Guide. This 1999-2000 edition presents 52 New Mexicans who deliver fascinating programs on New Mexico, Southwest, national and international topics. Making their debuts on the state stage are 16 new “living history” Chautauqua characters, ranging from an 1840s mountain man to Martha Washington, from Governor Lew Wallace to Capitán Rafael Chacón, from Pat Garrett to Harry Houdini and Kit Carson to Mabel Dodge Luhan. -

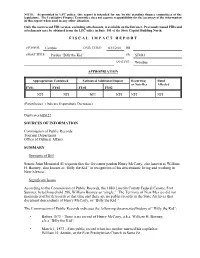

F I S C a L I M P a C T R E P O

NOTE: As provided in LFC policy, this report is intended for use by the standing finance committees of the legislature. The Legislative Finance Committee does not assume responsibility for the accuracy of the information in this report when used in any other situation. Only the most recent FIR version, excluding attachments, is available on the Intranet. Previously issued FIRs and attachments may be obtained from the LFC office in Suite 101 of the State Capitol Building North. F I S C A L I M P A C T R E P O R T SPONSOR: Campos DATE TYPED: 03/12/01 HB SHORT TITLE: Pardon “Billy the Kid” SB SJM43 ANALYST: Woodlee APPROPRIATION Appropriation Contained Estimated Additional Impact Recurring Fund or Non-Rec Affected FY01 FY02 FY01 FY02 NFI NFI NFI NFI NFI NFI (Parenthesis ( ) Indicate Expenditure Decreases) Duplicates HJM27 SOURCES OF INFORMATION Commission of Public Records Tourism Department Office of Cultural Affairs SUMMARY Synopsis of Bill Senate Joint Memorial 43 requests that the Governor pardon Henry McCarty, also known as William H. Bonney, also known as “Billy the Kid” in recognition of his descendants living and working in New Mexico. Significant Issues According to the Commission of Public Records, the 1880 Lincoln County Federal Census, Fort Sumner, listed household 286, William Bonney as “single.” The Territory of New Mexico did not maintain civil birth records at that time and there are no public records in the State Archives that document descendants of Henry McCarty, or “Billy the Kid.” The Commission of Public Records indicates the following documented history of “Billy the Kid”: • Before 1873 - There is no record of Henry McCarty, a.k.a. -

History, Dinã©/Navajo Memory, and the Bosque Redondo Memorial

New Mexico Historical Review Volume 82 Number 3 Article 2 7-1-2007 Discontinuities, Remembrances, and Cultural Survival: History, Diné/Navajo Memory, and the Bosque Redondo Memorial Jennifer Nez Denetdale Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/nmhr Recommended Citation Denetdale, Jennifer Nez. "Discontinuities, Remembrances, and Cultural Survival: History, Diné/Navajo Memory, and the Bosque Redondo Memorial." New Mexico Historical Review 82, 3 (2007). https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/nmhr/vol82/iss3/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in New Mexico Historical Review by an authorized editor of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected], [email protected]. Discontinuities, Remembrances, and Cultural Survival HISTORY, DINE/NAVAJO MEMORY, AND THE BOSQUE REDONDO MEMORIAL Jennifer Nez Denetdale n 4 June 2005, hundreds ofDine and their allies gathered at Fort Sumner, ONew Mexico, to officially open the Bosque Redondo Memorial. Sitting under an arbor, visitors listened to dignitaries interpret the meaning of the Long Walk, explain the four years ofimprisonment at the Bosque Redondo, and discuss the Navajos' return to their homeland in1868. Earlier that morn ing, a small gathering ofDine offered their prayers to the Holy People. l In the past twenty years, historic sites have become popular tourist attrac tions, partially as a result ofpartnerships between state historic preservation departments and the National Park Service. With the twin goals ofeducat ing the public about the American past and promoting their respective states as attractive travel destinations, park officials and public historians have also included Native American sites. -

In the Shadow of Billy the Kid: Susan Mcsween and the Lincoln County War Author(S): Kathleen P

In the Shadow of Billy the Kid: Susan McSween and the Lincoln County War Author(s): Kathleen P. Chamberlain Source: Montana: The Magazine of Western History, Vol. 55, No. 4 (Winter, 2005), pp. 36-53 Published by: Montana Historical Society Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/4520742 . Accessed: 31/01/2014 13:20 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp . JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Montana Historical Society is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Montana: The Magazine of Western History. http://www.jstor.org This content downloaded from 142.25.33.193 on Fri, 31 Jan 2014 13:20:15 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions In the Shadowof Billy the Kid SUSAN MCSWEEN AND THE LINCOLN COUNTY WAR by Kathleen P. Chamberlain S C.4 C-5 I t Ia;i - /.0 I _Lf Susan McSween survivedthe shootouts of the Lincoln CountyWar and createda fortunein its aftermath.Through her story,we can examinethe strugglefor economic control that gripped Gilded Age New Mexico and discoverhow women were forced to alter their behavior,make decisions, and measuresuccess againstthe cold realitiesof the period. This content downloaded from 142.25.33.193 on Fri, 31 Jan 2014 13:20:15 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions ,a- -P N1878 southeastern New Mexico declared war on itself. -

Frontier Culture: the Roots and Persistence of “Rugged Individualism” in the United States Samuel Bazzi, Martin Fiszbein, and Mesay Gebresilasse NBER Working Paper No

Frontier Culture: The Roots and Persistence of “Rugged Individualism” in the United States Samuel Bazzi, Martin Fiszbein, and Mesay Gebresilasse NBER Working Paper No. 23997 November 2017, Revised August 2020 JEL No. D72,H2,N31,N91,P16 ABSTRACT The presence of a westward-moving frontier of settlement shaped early U.S. history. In 1893, the historian Frederick Jackson Turner famously argued that the American frontier fostered individualism. We investigate the Frontier Thesis and identify its long-run implications for culture and politics. We track the frontier throughout the 1790–1890 period and construct a novel, county-level measure of total frontier experience (TFE). Historically, frontier locations had distinctive demographics and greater individualism. Long after the closing of the frontier, counties with greater TFE exhibit more pervasive individualism and opposition to redistribution. This pattern cuts across known divides in the U.S., including urban–rural and north–south. We provide evidence on the roots of frontier culture, identifying both selective migration and a causal effect of frontier exposure on individualism. Overall, our findings shed new light on the frontier’s persistent legacy of rugged individualism. Samuel Bazzi Mesay Gebresilasse Department of Economics Amherst College Boston University 301 Converse Hall 270 Bay State Road Amherst, MA 01002 Boston, MA 02215 [email protected] and CEPR and also NBER [email protected] Martin Fiszbein Department of Economics Boston University 270 Bay State Road Boston, MA 02215 and NBER [email protected] Frontier Culture: The Roots and Persistence of “Rugged Individualism” in the United States∗ Samuel Bazziy Martin Fiszbeinz Mesay Gebresilassex Boston University Boston University Amherst College NBER and CEPR and NBER July 2020 Abstract The presence of a westward-moving frontier of settlement shaped early U.S. -

Billy the Kid and the Lincoln County War 1878

Other Forms of Conflict in the West – Billy the Kid and the Lincoln County War 1878 Lesson Objectives: Starter Questions: • To understand how the expansion of 1) We have many examples of how the the West caused other forms of expansion into the West caused conflict with tension between settlers, not just Plains Indians – can you list three examples conflict between white Americans and of conflict and what the cause was in each Plains Indians. case? • To explain the significance of the 2) Can you think of any other groups that may Lincoln County War in understanding have got into conflict with each other as other types of conflict. people expanded west and any reasons why? • To assess the significance of Billy the 3) Why was law and order such a problem in Kid and what his story tells us about new communities being established in the law and order. West? Why was it so hard to stop violence and crime? As homesteaders, hunters, miners and cattle ranchers flooded onto the Plains, they not only came into conflict with the Plains Indians who already lived there, but also with each other. This was a time of robberies, range wars and Indian wars in the wide open spaces of the West. Gradually, the forces of law and order caught up with the lawbreakers, while the US army defeated the Plains Indians. As homesteaders, hunters, miners and cattle ranchers flooded onto the Plains, they not only came into conflict with the Plains Indians who already lived there, but also with each other. -

Review of Inventing Billy the Kid: Visions of the Outlaw in America, 1881-1981 by Stephen Tatum

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Great Plains Quarterly Great Plains Studies, Center for Summer 1984 Review of Inventing Billy the Kid: Visions of the Outlaw in America, 1881-1981 By Stephen Tatum Kent L. Steckmesser California State University-Los Angeles Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/greatplainsquarterly Part of the Other International and Area Studies Commons Steckmesser, Kent L., "Review of Inventing Billy the Kid: Visions of the Outlaw in America, 1881-1981 By Stephen Tatum" (1984). Great Plains Quarterly. 1798. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/greatplainsquarterly/1798 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Great Plains Studies, Center for at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Great Plains Quarterly by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. 182 GREAT PLAINS QUARTERLY, SUMMER 1984 biography was formulated as a "romance." As a "bad" badman, a threat to the moral order, the Kid had to die so that civilization-repre sented by Sheriff Pat Garrett-could advance. This formula of conflict and resolution by death can be detected in dime novels and early magazine accounts, which dwell on the Kid's unheroic appearance and bloodthirsty char acter. After a period of meager interest, by the mid-1920s a quite different figure was being molded by biographers and film makers. This was the prototypical "good" badman, one who personifies a kind of idealism. In Walter Noble Burns's key biography in 1926 and in a 1930 film, the Kid becomes a redeemer who helps small farmers. -

Promise Beheld and the Limits of Place

Promise Beheld and the Limits of Place A Historic Resource Study of Carlsbad Caverns and Guadalupe Mountains National Parks and the Surrounding Areas By Hal K. Rothman Daniel Holder, Research Associate National Park Service, Southwest Regional Office Series Number Acknowledgments This book would not be possible without the full cooperation of the men and women working for the National Park Service, starting with the superintendents of the two parks, Frank Deckert at Carlsbad Caverns National Park and Larry Henderson at Guadalupe Mountains National Park. One of the true joys of writing about the park system is meeting the professionals who interpret, protect and preserve the nation’s treasures. Just as important are the librarians, archivists and researchers who assisted us at libraries in several states. There are too many to mention individuals, so all we can say is thank you to all those people who guided us through the catalogs, pulled books and documents for us, and filed them back away after we left. One individual who deserves special mention is Jed Howard of Carlsbad, who provided local insight into the area’s national parks. Through his position with the Southeastern New Mexico Historical Society, he supplied many of the photographs in this book. We sincerely appreciate all of his help. And finally, this book is the product of many sacrifices on the part of our families. This book is dedicated to LauraLee and Lucille, who gave us the time to write it, and Talia, Brent, and Megan, who provide the reasons for writing. Hal Rothman Dan Holder September 1998 i Executive Summary Located on the great Permian Uplift, the Guadalupe Mountains and Carlsbad Caverns national parks area is rich in prehistory and history. -

Navajo Nation to Obtain an Original Naaltsoos Sání – Treaty of 1868 Document

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE May 22, 2019 Navajo Nation to obtain an original Naaltsoos Sání – Treaty of 1868 document WINDOW ROCK – Navajo Nation President Jonathan Nez and Vice President Myron Lizer are pleased to announce the generous donation of one of three original Navajo Treaty of 1868, also known as Naaltsoos Sání, documents to the Navajo Nation. On June 1, 1868, three copies of the Treaty of 1868 were issued at Fort Sumner, N.M. One copy was presented to the U.S. Government, which is housed in the National Archives and Records Administration in Washington D.C. The second copy was given to Navajo leader Barboncito – its current whereabouts are unknown. The third unsigned copy was presented to the Indian Peace Commissioner, Samuel F. Tappan. The original document is also known as the “Tappan Copy” is being donated to the Navajo Nation by Clare “Kitty” P. Weaver, the niece of Samuel F. Tappan, who was the Indian Peace Commissioner at the time of the signing of the treaty in 1868. “On behalf of the Navajo Nation, it is an honor to accept the donation from Mrs. Weaver and her family. The Naaltsoos Sání holds significant cultural and symbolic value to the Navajo people. It marks the return of our people from Bosque Redondo to our sacred homelands and the beginning of a prosperous future built on the strength and resilience of our people,” said President Nez. Following the signing of the Treaty of 1868, our Diné people rebuilt their homes, revitalized their livestock and crops that were destroyed at the hands of the federal government, he added. -

Fort Craig's 150Th Anniversary Commemoration, 2004

1854-1885 Craig Fort Bureau of Land Management Land of Bureau Interior the of Department U.S. The New Buffalo Soldiers, from Shadow Hills, California, reenactment at Fort Craig's 150th Anniversary commemoration, 2004. Bureau of Land Management Socorro Field Office 901 S. Highway 85 Socorro, NM 87801 575/835-0412 or www.blm.gov/new-mexico BLM/NM/GI-06-16-1330 TIMELINE including the San Miguel Mission at Pilabó, present day Socorro. After 1540 Coronado expedition; Area inhabited by Piro and Apache 1598 Spanish colonial era begins the 1680 Pueblo Revolt, many of the Piro moved south to the El Paso, 1821 Mexico wins independence from Spain Before Texas area with the Spanish, probably against their will. Others scattered 1845 Texas annexed by the United States and joined other Pueblos, leaving the Apache in control of the region. 1846 New Mexico invaded by U.S. General Stephen Watts Kearney; Territorial period begins The Spanish returned in 1692 but did not resettle the central Rio Grande 1849 Garrison established in Socorro 1849 –1851 hoto courtesyhoto of the National Archives Fort Craig P valley for a century. 1851 Fort Conrad activated 1851–1854 Fort Craig lies in south central New Mexico on the Rio Grande, 1854 Fort Craig activated El Camino Real de Tierra Adentro, or The Royal Road of the Interior, was with the rugged San Mateo Mountains to the west and a brooding the lifeline that connected Mexico City with Ohkay Owingeh, (just north volcanic mesa punctuating the desolate Jornada del Muerto to the east. of Santa Fe). -

THE FRONTIER in AMERICAN CULTURE (HIS 324-01) University of North Carolina at Greensboro, Spring 2014 Tuesday and Thursday 3:30-4:45Pm ~ Curry 238

THE FRONTIER IN AMERICAN CULTURE (HIS 324-01) University of North Carolina at Greensboro, Spring 2014 Tuesday and Thursday 3:30-4:45pm ~ Curry 238 Instructor: Ms. Sarah E. McCartney Email: [email protected] (may appear as [email protected]) Office: MHRA 3103 Office Hours: Tuesday and Thursday from 2:15pm-3:15pm and by appointment Mailbox: MHRA 2118A Course Description: Albert Bierstadt, Emigrants Crossing the Plains (1867). This course explores the ways that ideas about the frontier and the lived experience of the frontier have shaped American culture from the earliest days of settlement through the twenty- first century. Though there will be a good deal of information about the history of western expansion, politics, and the settlement of the West, the course is designed primarily to explore the variety of meanings the frontier has held for different generations of Americans. Thus, in addition to settlers, politicians, and Native Americans, you will encounter artists, writers, filmmakers, and an assortment of pop culture heroes and villains. History is more than a set of facts brought out of the archives and presented as “the way things were;” it is a careful construction held together with the help of hypotheses and assumptions.1 Therefore, this course will also examine the “construction” of history as you analyze primary sources, discuss debates in secondary works written by historians, and use both primary and secondary sources to create your own interpretation of history. Required Texts: Robert V. Hine and John Mack Faragher. Frontiers: A Short History of the American West. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2007.