4. the Water of Leith As Stated in the Introduction, the Format of This

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

S. Edinburgh a Sweep Past Sixteen Old Curling Ponds

South Edinburgh COVID-19 bubble: a sweep past 16 curling ponds - 6 mile walk visiting sixteen old curling localities Start: Blackford Pond Gazebo, Cluny Dr., Braid Av., Cluny Av., Morningside Rd., Millar Cres., Royal Ed., Community Garden, Myreside railway path, Craiglockhart Ter., Craiglockhart Pond, Leisure Cente, Craiglockhart Wood, Grounds of Craig House, East Craiglockhart Hill (250ft ascent, mainly on steps), Comiston Dr., Greenbank Cres., Braid Rd., Hermitage, Blackford Pond, End. The map (above) and images below come from www.historicalcurlingplaces.org which is the website of the team researching old curling places across the country. The place numbers relate to those in their database. Otherwise historical map clippings come from the NLS site and were derived using Digimap (an online map and data delivery service operated by EDINA at the University of Edinburgh. Local ponds 2095 Hope Terrace, Edinburgh. Curling pond marked on Barthololmew's map of 1891. 0520 Blackford Pond, Edinburgh. Curling pond marked on Bartholomews map of 1893. 1886 Braid Estate, Edinburgh. Curling pond marked on OS 6inch map of 1909. 3111 Royal Edinburgh Hospital, rectangular pond. Curling pond marked on OS town plan of 1893. 2094 Royal Edinburgh Hospital, oval curling pond 250 ft long; maps of 1898 & 1909. 0668 Myreside, Edinburgh. Curling ponds marked on OS 25inch map of 1908. 2016 Union Canal, Edinburgh. Location near here identified in the Caledonian Mercury in February 1855. 1879 Waverley artificial pond on concrete base. Waverley Curling Club formed 1901. 0632 Craiglockhart. Curling ponds in deep glacial valley of Megget Burn. Curling Club formed 1887. 2184 Craiglockhart Hospital. Rectangular curling pond in grounds of New Craig House; Map 1909 & 1938. -

Edinburgh PDF Map Citywide Website Small

EDINBURGH North One grid square on the map represents approximately Citywide 30 minutes walk. WATER R EAK B W R U R TE H O A A B W R R AK B A E O R B U H R N R U V O O B I T R E N A W A H R R N G Y E A T E S W W E D V A O DRI R HESP B BOUR S R E W A R U H U H S R N C E A ER R P R T O B S S S E SW E O W H U A R Y R E T P L A HE B A C D E To find out more To travel around Other maps SP ERU W S C Royal Forth K T R OS A E S D WA E OA E Y PORT OF LEITH R Yacht Club R E E R R B C O T H A S S ST N L W E T P R U E N while you are in the Edinburgh and go are available to N T E E T GRANTON S S V V A I E A E R H HARBOUR H C D W R E W A N E V ST H N A I city centre: further afield: download: R S BO AND U P R CH RO IP AD O E ROYAL YACHT BRITANNIA L R IMPERIAL DOCK R Gypsy Brae O A Recreation Ground NEWHAVEN D E HARBOUR D Debenhams A NUE TON ROAD N AVE AN A ONT R M PL RFR G PIE EL SI L ES ATE T R PLA V ER WES W S LOWE CE R KNO E R G O RAN S G T E 12 D W R ON D A A NEWHAVEN MAIN RO N AD STREET R Ocean R E TO RIN K RO IV O G N T IT BAN E SH Granton RA R Y TAR T NT O C R S Victoria Terminal S O A ES O E N D E Silverknowes Crescent VIE OCEAN DRIV C W W Primary School E Starbank A N Golf Course D Park B LIN R OSWALL R D IV DRI 12 OAD Park SA E RINE VE CENT 13 L Y A ES P A M N CR RIMR R O O V O RAN T SE BA NEWHAVEN A G E NK RO D AD R C ALE O Forthquarter Park R RNV PORT OF LEITH & A O CK WTH 14 ALBERT DOCK I HA THE SHORE G B P GRANTON H D A A I O LT A Come aboard a floating royal N R W N L O T O O B K D L A W T A O C O R residence or visit the dockside bars Scottish N R N T A N R E E R R Y R S SC I E A EST E D L G W N O R D T D O N N C D D and bistros; steeped in maritime S A L A T E A E I S I A A Government DRI Edinburgh College I A A M K W R L D T P E R R O D PA L O Y D history and strong local identity. -

North Vorthumberland

Midlothian Vice-county 83 Scarce, Rare & Extinct Vascular Plant Register Silene viscaria Vicia orobus (© Historic Scotland Ranger Service) (© B.E.H. Sumner) Barbara E.H. Sumner 2014 Rare Plant Register Midlothian Asplenium ceterach (© B.E.H. Sumner) The records for this Register have been selected from the databases held by the Botanical Society of Britain and Ireland. These records were made by botanists, most of whom were amateur and some of whom were professional, employed by government departments or undertaking environmental impact assessments. This publication is intended to be of assistance to conservation and planning organisations and authorities, district and local councils and interested members of the public. Acknowledgements My thanks go to all those who have contributed records over the years, and especially to Douglas R. McKean and the late Elizabeth P. Beattie, my predecessors as BSBI Recorders for Midlothian. Their contributions have been enormous, and Douglas continues to contribute enthusiastically as Recorder Emeritus. Thanks also to the determiners, especially those who specialise in difficult plant groups. I am indebted to David McCosh and George Ballantyne for advice and updates on Hieracium and Rubus fruticosus microspecies, respectively, and to Chris Metherell for determinations of Euphrasia species. Chris also gave guidelines and an initial template for the Register, which I have customised for Midlothian. Heather McHaffie, Phil Lusby, Malcolm Fraser, Caroline Peacock, Justin Maxwell and Max Coleman have given useful information on species recovery programmes. Claudia Ferguson-Smyth, Nick Stewart and Michael Wilcox have provided other information, much appreciated. Staff of the Library and Herbarium at the Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh have been most helpful, especially Graham Hardy, Leonie Paterson, Sally Rae and Adele Smith. -

Chester Street, Edinburgh, EH3

Chester Street, Edinburgh Chester Street, The Property This is a superb first floor drawing room flat Edinburgh, located in the heart of Edinburgh’s West End. EH3 7RA The property has retained many fine period features, particularly in the grand sitting room/ A superb 2-bedroom first floor drawing dining room, including ornate cornice work, room flat in the heart of Edinburgh’s a ceiling rose, a beautiful wooden fireplace, working shutters, full length sash and case West End. windows and the original balcony along the front three windows. First floor: Hall | Sitting room/dining room Kitchen | Master bedroom | Double bedroom 2 The accomodation further comprises of two Family bathroom | Two large storage cupboards. well-proportioned double bedrooms (one with largewardrobe), a family bathroom and the EPC Rating: D kitchen. The kitchen has Siemens appliances with an integrated fridge/freezer, dishwasher Situation and washing machine. The property also Chester Street is situated in a central location in benefits from ample storage with two large the heart of Edinburgh’s prestigious West End. cupboards. The property is within a few minutes’ walk of the retail, financial and commercial city centre in Princes Street, George Street and Lothian Road and also has easy access to Haymarket Station. The fashionable and ever-popular West End is host to a wide variety of amenities including bars, shops, boutiques and restaurants. There is also a Co-Operative and a Sainsbury’s Local supermarkets on Shandwick Place. Local amenities include the Drumsheugh Private Swimming Baths, the Edinburgh Sports Club, Dean Tennis Club and the Modern and Dean Art Galleries. -

31 Balgreen Road Balgreen Edinburgh Eh12 5Ty Offers

31 BALGREEN ROAD BALGREEN OFFERS OVER EDINBURGH £630,000 EH12 5TY SPACIOUS DETACHED VILLA WITH LARGE REAR GARDEN AND LOCATED IN A POPULAR AREA CLOSE TO EXCELLENT VIEWING: LOCAL AMENITIES BY APPOINTMENT AND THE CITY TELEPHONE AGENTS 0131 524 3800 FOR CENTRE AN APPOINTMENT Spacious detached villa providing flexible family accommodation in the popular residential area of Balgreen. Balgreen Road is located approximately two miles west of the city centre. The grounds of Murrayfield lie to the east and to the south is Carricknowe Golf Course and Saughton Park. Within close walking distance are Edinburgh Zoo and Corstorphine Hill which offers superb walks within the City. Locally there are a number of useful shops at Western Corner, Saughtonhall Drive, St. John's Road and Corstorphine which offers an exceptionally wide range of shops, banking, building society and post office services. Larger Sainsburys and a 24 hour Tesco supermarkets are also nearby and the Gyle Shopping Centre is just a short drive away. There is a local tram stop and Haymarket Railway station is also easily reached. There are excellent road links to Edinburgh Airport, Edinburgh City Bypass and Motorways linking to Central Scotland. Regular buses run close by and provide quick and easy access to the city centre. Internally the property offers exceptionally spacious and flexible family accommodation and is in good decorative order throughout with the benefit of gas central heating and double glazing. The integrated kitchen appliances are included in the sale together with all fitted carpets and blinds. A driveway provides off street parking and leads to large single garage. -

Pageflex Server

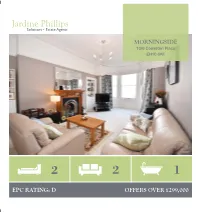

MORNINGSIDE 10/6 Comiston Place EH10 6AF 2 2 1 EPC RATING: D OFFERS OVER £299,000 PROPERTY DESCRIPTION • Bedroom 2, another double room, set quietly to the rear with • Hall with oak flooring, cornice and two walk in shelved cornice and view south, over shared gardens cupboards • Study, a flexible room with two full length storage cupboards • Elegant lounge with ornate cornice, centre rose, living flame at the entrance and borrowed light from a high level opening gas fire in a handsome mantelpiece and bay window having into the kitchen lovely views to Braid Hills and Salisbury Crags • Bathroom with modern white three piece suite including a • Smartly fitted kitchen/diner, another generously power shower over the bath proportioned room with ample units, gas cooker, stainless • Gas central heating steel extractor, integrated dishwasher, separate dining • Part double glazing to the rear recess and walk in cupboard • Entryphone system and residents pay for stair cleaning • Bedroom1, an extremely large double room with cornice, • Attractive shared garden to the rear and residents pay for picture rail, a fine mantelpiece and twin window with views grass cutting to Salisbury Crags • Permit parking in the street between 1.30-3 pm but unrestricted on street parking outside these times VIEWING Sun 2-4 pm or by apmt tel 0131 446 6850 DESIRABLE TOP FLOOR FLAT Located in a small street off Comiston Road in the heart of Morningside, close to all facilities, this traditional property has spacious accommodation which is very well presented and has been modernised into a lovely flat while retaining some fine period features LOCATION DIRECTION Located in southern Morningside, within Travelling south out Morningside Road, Morningside Conservation Area, close to a good continue over at the crossroads into selection of local shops, this flat is also well Comiston Road. -

This Is the Title. It Is Arial 16Pt Bold

Green Flag Award Park Winners 2017 Local Authority Park Name New Aberdeen City Council Duthie Park Aberdeen City Council Hazlehead Park Aberdeen City Council Johnston Gardens Y Aberdeen City Council Seaton Park Aberdeenshire Council Aden Country Park Aberdeenshire Council Haddo Park Dumfries & Galloway Council Dock Park Dundee City Council Barnhill Rock Garden Dundee City Council Baxter Park Trottick Mill Ponds Local Nature Dundee City Council Reserve Dundee City Council Dundee Law Y Dundee City Council Templeton Woods East Renfrewshire Council Rouken Glen Park Edinburgh Braidburn Valley Park Edinburgh Burdiehouse Burn Valley Park Edinburgh Corstorphine Hill Edinburgh Craigmillar Castle Park Edinburgh Easter Craiglockhart Hill Edinburgh Ferniehill Community Park Edinburgh Ferry Glen & Back Braes Edinburgh Figgate Burn Park www.keepscotlandbeautiful.org 1 Edinburgh Hailes Quarry Park Edinburgh Harrison Park Hermitage of Braid inc Blackford Hill Edinburgh & Pond Edinburgh Hopetoun Crescent Gardens Edinburgh Inverleith Park Edinburgh King George V Park, Eyre Place Edinburgh Lochend Park Edinburgh London Road Gardens Edinburgh Morningside Park Edinburgh Muirwood Road Park Edinburgh Pentland Hills Regional Park Edinburgh Portobello Community Garden Edinburgh Prestonfield Park Edinburgh Princes Street Gardens Edinburgh Ravelston Park & Woods Edinburgh Rosefield Park Edinburgh Seven Acre Park Edinburgh Spylaw Park Edinburgh St Margarets Park Edinburgh Starbank Park Edinburgh Station Road Pk, S Queensferry Edinburgh Victoria Park Falkirk Community -

Edinburgh's Local Geodiversity Sites

Edinburgh’s Local Geodiversity Sites Lothian and Borders GeoConservation www.edinburghgeolsoc.org/home/geoconservation/local-geodiversity-sites-edinburgh/ In Edinburgh, 30 sites of geological interest have been designated as Local Nature Conservation Sites 26 Local Geodiversity Sites are places where the varied geology of the South Queensferry Shore local area can be enjoyed and appreciated. In Edinburgh, 30 sites have been 20 Hunter’s Craig to Snab Point designated as Local Nature Conservation Sites by the City of Edinburgh Craigie Hill 10 25 River Almond:Cramond Council in partnership with Lothian and Borders GeoConservation and INVERLEITH included in the City Local Development Plan. Craigleith Quarry 11 Water of Leith Calton Hill Corstorphine Hill Stockbridge 6 1 2 3 4 5 9 24 27 Stones of Scotland 30 21 Ravelston 7 Canongate Wall 8 Joppa Shore Woods Castle Rock 16 Dynamic Earth SOUTH GYLE 22 Ratho Quarry Craiglockhart Hill 12 13 Craigmillar Balm Well Bavelaw Blackford Hill Braid Hills Caerketton Screes 6 7 8 9 10 3 Blackford Hill Water of Leith:Colinton Dell 29 OXGANGS Ellen’s Glen 4 Braid Hills 17 CURRIE Fairmilehead Park 18 Balm Well 1 GRACEMOUNT Dreghorn Link 15 Dalmahoy & 14 Ravelrig Quarry Calton Hill Canongate Wall Castle Rock Corstorphine Hill Craigie Hill Kaimes Hills 23 28 Torphin Quarry 11 12 13 14 15 5 Caerketton Screes 19 Harlaw Resevoir Craigleith Quarry Craiglockhart Hill Craigmillar Dalmahoy & Kaimes Hills Dreghorn Link PENTLAND HILLS Bavelaw 2 16 17 18 19 20 2 1. A natural oil seepage linked to the nearby 16. Displays around the outdoor amphitheatre Pentland Fault. -

Charming Upper Colony Flat with Wonderful Open Views 33 Reid Terrace Stockbridge, Edinburgh, Eh3 5Jh Charming Upper Colony Flat with Wonderful Open Views

CHARMING UPPER COLONY FLAT WITH WONDERFUL OPEN VIEWS 33 reid terrace stockbridge, edinburgh, eh3 5jh CHARMING UPPER COLONY FLAT WITH WONDERFUL OPEN VIEWS 33 reid terrace stockbridge, edinburgh, eh3 5jh Maindoor entrance w reception hall w sitting room w dining kitchen w 3 bedrooms w study w bathroom w WC w floored attic w private front garden w EPC rating=E Location Reid Terrace is located in the Stockbridge Colonies, a tranquil little haven in a delightful part of Edinburgh, bursting with character and charm, but within walking distance of Princes Street. Cosmopolitan Stockbridge has a strong sense of community with its own library, primary schools and Glenogle Swim Centre and a village atmosphere with its weekly Farmers Market and annual Duck Race. It has a splendid choice of galleries, gift and specialist food shops, bistros, pubs and restaurants and a Waitrose in the near vicinity. There are pleasant walks to the enchanting Dean Village and along The Water of Leith as well as the open spaces of Inverleith Park and the Royal Botanic Gardens. There is excellent access to a number of local state and public schools and a regular bus service to the city centre. Description 33 Reid Terrace is a charming double upper colony flat in a wonderful location with open views over the Water of Leith, Grange Cricket Club and beyond. The property benefits from a maindoor entrance and has flexible accommodation arranged over two floors with the main living area on the lower level and bedroom accommodation on the upper level. There is also a large floored attic with a velux window, which can be accessed from the upper floor. -

CARRY on STREAMIN from EDINBURGH FOLK CLUB Probably the Best Folk Club in the World! Dateline: Wednesday 16 September 2020 Volume 1.08

CARRY ON STREAMIN from EDINBURGH FOLK CLUB Probably the best folk club in the world! Dateline: Wednesday 16 September 2020 Volume 1.08 TRADITION WORKS IN THE project in 3 pilot areas in Scotland, a team of ten practitioners. We piloted the project, CARRY ON STREAMIN COMMUNITY, NATURALLY which was forensically logged and You may recognise in our banner a A trad muso’s journey working with evaluated, with great results, and went on ‘reworking’ of the of the Carrying people living with dementia to train a range of professionals - Stream festival which EFC’s late chair, including librarians and activities co- Paddy Bort, created shortly after the ordinators in care home and care settings, death of Hamish Henderson. in some of our methods. After Paddy died in February 2017, We all, in our own way, broadened the EFC created the Paddy Bort Fund scope beyond the curated conversation (PBF) to give financial assistance to into creative areas, such as crafts, folk performers who, through no fault songmaking, working with words. The of their own, fall on hard times. project was highly successful but no No-one contemplated anything like the further funding could be found past the coronavirus. Now we need to ‘training others’ phase. replenish PBF and have set a target of Christine Kydd: pic Louise Kerr Since, however, I’ve used the model in (at least) £10 000. various settings including as part of a large There are two strands to Carry On Christine Kydd writes ... project (delivered by my Ceilidhmakers Streamin - this publication and our This article tell you about how I got into brand with Ewan McVicar), called Telling YouTube channel where you will find, working with people who live with our Stories, for the Tay Landscape every fortnight, videos donated by Dementia, and just one of the projects that Partnership, and also in Kirrie some of the best folk acts around. -

Petitions Committee Response

PE1095/G Franck David Assistant Clerk to the Public Petitions Committee Tower 4, TG.01 The Scottish Parliament Holyrood EH99 1SP Dear Franck David, Public Petitions Committee response. Further to your email of 17th December regarding your request for a response to the petition received by your committee from the Pentland Hills Regional Park. Background information The designation of the Pentland Hills Regional Park was confirmed until September 1986, following the outcome of a public inquiry. The designation was made under section 48(A) of the Countryside (Scotland) Act 1967 .Initially the Pentland Hills Regional Park was operated by Lothian Regional Council who prepared a Subject Local Plan to guide the Pentland Hills Regional Park policies and management. The policies relevant to the Pentland Hills Regional Park contained within the former Lothian Regional Council’s Subject Local Plan were then incorporated into the local plans of the respective three unitary authorities. Pentland Hills Regional Park is currently covered by the City of Edinburgh Council’s Finalised Rural West Edinburgh Local Plan (2003); Midlothian Council’s Adopted Local Plan (2003) and the West Lothian Local Plan Finalised (2005). The aim of Regional Park designation is to cover extensive areas of land, in diverse ownership, where provision for public recreation is given a higher profile by establishing a co-ordinated framework for the integrated management of recreation with traditional land use in close collaboration with local interests. National Planning Policy Guidance (NPPG) 14 (s.21) states that Regional Parks play a valuable role in providing opportunities for urban populations to gain access to attractive areas of countryside for recreation and enjoyment of the natural heritage. -

The Daniel Wilson Scrapbook

The Daniel Wilson Scrapbook Illustrations of Edinburgh and other material collected by Sir Daniel Wilson, some of which he used in his Memorials of Edinburgh in the olden time (Edin., 1847). The following list gives possible sources for the items; some prints were published individually as well as appearing as part of larger works. References are also given to their use in Memorials. Quick-links within this list: Box I Box II Box III Abbreviations and notes Arnot: Hugo Arnot, The History of Edinburgh (1788). Bann. Club: Bannatyne Club. Beattie, Caledonia illustrated: W. Beattie, Caledonia illustrated in a series of views [ca. 1840]. Beauties of Scotland: R. Forsyth, The Beauties of Scotland (1805-8). Billings: R.W. Billings, The Baronial and ecclesiastical Antiquities of Scotland (1845-52). Black (1843): Black’s Picturesque tourist of Scotland (1843). Black (1859): Black’s Picturesque tourist of Scotland (1859). Edinburgh and Mid-Lothian (1838). Drawings by W.B. Scott, engraved by R. Scott. Some of the engravings are dated 1839. Edinburgh delineated (1832). Engravings by W.H. Lizars, mostly after drawings by J. Ewbank. They are in two series, each containing 25 numbered prints. See also Picturesque Views. Geikie, Etchings: Walter Geikie, Etchings illustrative of Scottish character and scenery, new edn [1842?]. Gibson, Select Views: Patrick Gibson, Select Views in Edinburgh (1818). Grose, Antiquities: Francis Grose, The Antiquities of Scotland (1797). Hearne, Antiquities: T. Hearne, Antiquities of Great Britain illustrated in views of monasteries, castles and churches now existing (1807). Heriot’s Hospital: Historical and descriptive account of George Heriot’s Hospital. With engravings by J.