Welsh Historic Churches Project

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Abergavenny Town & Villages Llanfoist Govilon Gilwern

JUNE 2019 ISSUE 144 THE ABERGAVEN NY FOCUSYOUR FREE COMMUNITY MAGAZINE, PROMOTING LOCAL BUSINESSES Colour! ABERGAVENNY TOWN & VILLAGES LLANFOIST GOVILON GILWERN Home is Everything HOMES FROM PARRYS 21 Nevill Street, Abergavenny, Monmouthshire NP7 5AA 01873 736515 | [email protected] | www.fineandcountry.com Your local & independent Your localagent & independent providing expertise, serviceYour local and &results independent agent providingagent expertise, providing expertise, service andWeservice currentlyYourresults have localand more of ourresults &properties independent under offer than any of our competitors. agent providing expertise, We currently have more of our properties under offer than any of We currently have moreIf you of ourservice properties are underlooking offer than any toof buy,and sell, letresults or rent come and see us or call on our competitors. 01873 852221 to discuss your needs. our competitors. We currently have more of our properties under offer than any of our competitors. If youYour are looking local to buy, sell, let& or independent rent come and see us or call on 01873 852221 to discuss your needs. If you are looking to buy, sell,YouragentIf let youor rent come are and seelooking us orlocal callproviding on to buy, sell, & let independentor rent comeexpertise, and see us or call on 01873 852221 to discuss your needs. 01873 852221 to discuss youragentservice needs. providing and results expertise, Chartered Surveyors | Estate, Land & Letting Agents | Auctioneers | Planning Consultants | Building Design www.ChristieResidential.co.uk | 53 Cross Street, Abergavenny, NP7 5EU Rural Residential Commercial Design service and results YourWe Independentcurrently have more andof our propertiesTruly Local under offer Property than any of Experts DJ&P NEWLAND RENNIE | WALES | GOLD WINNER | SALES our competitors. -

Town Barn Grosmont, Monmouthshire, NP7 8EP

Town Barn Grosmont, Monmouthshire, NP7 8EP Local Independent Professional Town Barn Grosmont, Monmouthshire, NP7 8EP Nestled in the valley of the River Monnow, enjoying a glorious position and affording stunning views in the heart of this most favoured village, Town Barn is a luxurious Grade II listed barn conversion. Believed to be around 400 years old, this fabulous home is a beautifully inspired and stylish residence, harmonising an elegant interior with superb character features and fine attention to individual details. Town Barn is an exceptionally handsome residence, displaying an attractive mix of stone complemented by weather boarding. Sumptuously decorated with an elegant presentation, the property has been converted to an extremely high specification to include a bespoke hand crafted kitchen, contemporary bathroom suites, a combination of oak and limestone flooring with underfloor heating to the ground floor, stone walling accompanied by arrow slit windows, magnificent vaulted ceilings to the bedrooms, exposed roof trusses and beams, and an oak staircase opening onto an impressive galleried landing flooded with light and boasting a double height vaulted ceiling. TheThe accomm ancient odationvillage of includes Grosmont an openis renowned plan reception for its hospitality, hall/dining an/reception historic roomchurch with and study castle, area, and sitting its well room-regarded with period sense style of community. gas fire and Llargeocal farmhousefacilities in style this kitchen the village and utilityinclude room the andAngel galleried Inn and landing, a post largeoffice. master The areabedroom, is well en known suite and for threeits outdoor further pursuits double bedroincludingoms hilland walkin bathroom.g along The propertythe famous benefits Offa’s from Dyke a hard pathway standing and parking the Monnow area and Valley Detached walk, Garage/Carpony trekking, port and with of landscaped course, cycling gardens along including the national a terraces, cycle lawn rou te.and well stocked flower beds. -

Monmouthshire Meadows Group

Issue 12 December 2009 MONMOUTHSHIRE MEADOWS GROUP Aim - To conserve and enhance the landscape by enabling members to maintain, manage and restore their semi-natural grasslands and associated features. Contents visitor numbers rather low. Despite sell the hay bales but most fields this the event was much enjoyed weren‟t cut until the end of August 1. From the Chair. by those who did brave the or into September. Some of your elements. grazing pastures benefitted from 2. Poisonous Plants and Ron Shear‟s sheep or our own two Two popular sites – the orchard Grazing Animals Exmoor Ponies. Other activities by and meadow at Ty Mawr convent 3. Haymaking 2009 members of the committee and Ida Dunn‟s flower-rich fields at 4. Peter Chard. Memories of a included facilitating Bracken Maryland were open to the public friend. spraying at two sites on Lydart and again but we also had three „new‟ 5. Umbellifers in moving 90 bales of hay at Ty Mawr sites on show. One of these was a under cover. Monmouthshire series of small fields and adjacent 6. Our Carbon footprint woodland owned by Walter Keeler Surveys of new members’ fields 7. Tribute to Catherine at Penallt where a fine show of and provision of advice take up Sainsbury spotted orchids including hybrid time too. We have surveyed 8. Work Tasks Common Spotted x Heath Spotted grasslands in the Whitebrook 9. Dates for your diary were in evidence as well as Valley, at Far Hill, Cwmcarvan, at 10. Welcome to new members. Southern Marsh Orchid. Our Mitchel Troy common where a 11. -

Caerphilly County Borough Council – Service User Perspective Review

Service User Perspective Review – Caerphilly County Borough Council Audit year: 2017- 2018 Date issued: November 2018 Document reference: 826A2018-19 This document has been prepared as part of work performed in accordance with statutory functions. In the event of receiving a request for information to which this document may be relevant, attention is drawn to the Code of Practice issued under section 45 of the Freedom of Information Act 2000. The section 45 code sets out the practice in the handling of requests that is expected of public authorities, including consultation with relevant third parties. In relation to this document, the Auditor General for Wales and the Wales Audit Office are relevant third parties. Any enquiries regarding disclosure or re-use of this document should be sent to the Wales Audit Office at [email protected]. We welcome correspondence and telephone calls in Welsh and English. Corresponding in Welsh will not lead to delay. Rydym yn croesawu gohebiaeth a galwadau ffôn yn Gymraeg a Saesneg. Ni fydd gohebu yn Gymraeg yn arwain at oedi. [Mae’r ddogfen hon hefyd ar gael yn Gymraeg. This document is also available in Welsh.] The team who delivered the work comprised Gareth Jones, Kevin Sutch, Matthew Brushett and Lisa McCarthy programme managed by Non Jenkins under the direction of Huw Rees. Contents Tenants and leaseholders have positive views about many aspects of the Council’s WHQS programme including the quality, but are less satisfied with external works, the timeliness of work, and the extent to which the Council involves them and provides information on the works. -

Monmouthshire Local Development Plan (Ldp) Proposed Rural Housing

MONMOUTHSHIRE LOCAL DEVELOPMENT PLAN (LDP) PROPOSED RURAL HOUSING ALLOCATIONS CONSULTATION DRAFT JUNE 2010 CONTENTS A. Introduction. 1. Background 2. Preferred Strategy Rural Housing Policy 3. Village Development Boundaries 4. Approach to Village Categorisation and Site Identification B. Rural Secondary Settlements 1. Usk 2. Raglan 3. Penperlleni/Goetre C. Main Villages 1. Caerwent 2. Cross Ash 3. Devauden 4. Dingestow 5. Grosmont 6. Little Mill 7. Llanarth 8. Llandewi Rhydderch 9. Llandogo 10. Llanellen 11. Llangybi 12. Llanishen 13. Llanover 14. Llanvair Discoed 15. Llanvair Kilgeddin 16. Llanvapley 17. Mathern 18. Mitchell Troy 19. Penallt 20. Pwllmeyric 21. Shirenewton/Mynyddbach 22. St. Arvans 23. The Bryn 24. Tintern 25. Trellech 26. Werngifford/Pandy D. Minor Villages (UDP Policy H4). 1. Bettws Newydd 2. Broadstone/Catbrook 3. Brynygwenin 4. Coed-y-Paen 5. Crick 6. Cuckoo’s Row 7. Great Oak 8. Gwehelog 9. Llandegveth 10. Llandenny 11. Llangattock Llingoed 12. Llangwm 13. Llansoy 14. Llantillio Crossenny 15. Llantrisant 16. Llanvetherine 17. Maypole/St Maughans Green 18. Penpergwm 19. Pen-y-Clawdd 20. The Narth 21. Tredunnock A. INTRODUCTION. 1. BACKGROUND The Monmouthshire Local Development Plan (LDP) Preferred Strategy was issued for consultation for a six week period from 4 June 2009 to 17 July 2009. The results of this consultation were reported to Council in January 2010 and the Report of Consultation was issued for public comment for a further consultation period from 19 February 2010 to 19 March 2010. The present report on Proposed Rural Housing Allocations is intended to form the basis for a further informal consultation to assist the Council in moving forward from the LDP Preferred Strategy to the Deposit LDP. -

Minutes of the Meeting Held on the 21 January 2020

Minutes of the meeting held on the 21 January 2020. PRESENT Clrs Davies, Evans, Morgan-Evans, Keates, Bentley, R Morgan, Catley, Rippin and Cty Clr Jones. Also present were the representatives of LRM Planning, Monmouthshire Housing Association and P&P Builders as well as a good number of local residents. APOLOGIES Clrs T Morgan, Phillips and Woodier. The first item on the Agenda was a DISCUSSION/QUESTION AND ANSWER SESSION with members of the public, councillors and the three representatives of MHA, P&P Builders and LRM Planning participating in a lively debate re the proposed housing development on Land to the South-West of Wern Gifford. Further clarification was sought by those present on issues already raised by the Community Council and private members of the public in their initial Pre- Application Response to the three organisations above as well as to Welsh Water/Dwr Cymru who were not present on the night but who would be attending the next Community Council Meeting on the 18 February. In no particular order of concern, the following points were raised: 1. Contrary to policy already outlined by MCC, relating to its preference for mixed housing developments, it was observed that this was a development relating completely to social/affordable housing. The answer given was that this was because partial grant funding had been obtained from the Welsh Government. 2. Access to the development (both when under construction and afterwards ) would have an enormous environmental impact owing to the increased traffic flow into Wern Gifford Estate especially around the Primary School entrance with children’s safety issues already a great concern. -

Monmouthshire County Council Weekly List of Registered Planning

Monmouthshire County Council Weekly List of Registered Planning Applications Week 31/05/2014 to 06/06/2014 Print Date 09/06/2014 Application No Development Description Application Type SIte Address Applicant Name & Address Agent Name & Address Community Council Valid Date Plans available at Easting / Northing Caerwent DC/2013/01065 Proposed new stone boundary walls & timber personnel gates providing improved security Planning Permission adjacent public highway. Original extant permission ref no. M/1232. Brook House Cottage Mr B McCusker & Mrs L Winterbourne Buckle Chamberlain Partnership Crick Brook Cottage Mill House Chepstow Crick Llancayo Court NP26 5UW Chepstow Llancayo NP26 5UW Usk NP15 1HY Caerwent 23 May 2014 348,877 / 190,201 DC/2014/00643 DC/2013/00670 - Discharge of condition 5 (Programme of archaeological work). Discharge of Condition Five Lanes Farm William Jones Lyndon Bowkett Designs Five Lanes Carrow Hill Farm 72 Caerau Road Caerwent Carrow Hill Newport Caldicot St Brides NP20 4HJ NP26 5PE Netherwent Caldicot NP26 3AU Caerwent 28 May 2014 344,637 / 190,589 DC/2014/00113 Outline application for dwelling at the rear of myrtle cottage Outline Planning Permission Myrtle Cottage Mrs Gail Harris James Harris The Cross Myrtle Cottage Myrtle Cottage Caerwent The Cross The Cross Caldicot Caerwent Caerwent NP26 5AZ Caldicot Caldicot NP26 5AZ NP26 5AZ Caerwent 03 June 2014 346,858 / 190,587 Caerwent 3 Print Date 09/06/2014 MCC Pre Check of Registered Applications 31/05/2014 to 06/06/2014 Page 2 of 15 Application No Development Description Application Type SIte Address Applicant Name & Address Agent Name & Address Community Council Valid Date Plans available at Easting / Northing Dixton With Osbaston DC/2013/00946 Seperation of the property into two dwellings. -

Print Finishers

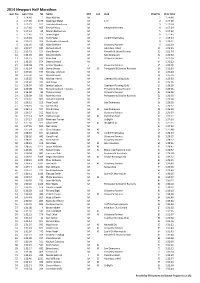

2014 Newport Half Marathon Gun Pos Gun Time No Name M/F Cat Club Chip Pos Chip Time 1 1:14:46 1 Ryan McFlyn M 1 1:14:46 2 1:17:09 1175 Matthew Welsh M 1 Tri 2 1:17:08 3 1:17:15 910 Leighton Rawlinson M 3 1:17:14 4 1:17:30 865 Emrys Penny M Newport Harriers 4 1:17:29 5 1:17:43 68 Maciej Bialogonski M 5 1:17:42 6 1:17:46 316 James Elgar M 6 1:17:45 7 1:19:35 372 Tom Foster M Cardiff Triathletes 7 1:19:34 8 1:20:33 926 Christopher Rennick M 8 1:20:31 9 1:21:10 425 Mike Griffiths M Lliswerry Runners 9 1:21:09 10 1:21:27 680 Richard Lloyd M Aberdare VAAC 10 1:21:25 11 1:21:52 117 Gary Brown M Penarth & Dinas Runners 11 1:21:50 12 1:22:03 801 Doug Nicholls M San Domenico 12 1:22:02 13 1:22:21 625 Alun King M Lliswerry Runners 13 1:22:18 14 1:22:25 574 Dean Johnson M 14 1:22:22 15 1:22:38 772 Emma Wookey F Lliswerry Runners 15 1:22:36 16 1:22:54 256 Steve Davies M 50 Pontypool & District Runners 16 1:22:52 17 1:25:26 575 Nicholas Johnson M 17 1:25:24 18 1:25:50 597 Richard Jones M 18 1:25:39 19 1:25:55 458 Michael Harris M Caerleon Running Club 19 1:25:53 20 1:26:02 163 Jack Casey M 20 1:25:56 21 1:26:07 162 James Casburn M Caerleon Running Club 22 1:26:05 22 1:26:08 541 Richard Jackson-Hookins M Penarth & Dinas Runners 23 1:26:06 23 1:26:09 82 Thomas Bland M Lliswerry Runners 24 1:26:06 24 1:26:09 531 Mark Hurford M Pontypool & District Runners 21 1:26:03 25 1:26:10 803 Daniel Oakenfull M 25 1:26:08 26 1:26:12 215 Pete Croall M San Domenico 26 1:26:10 27 1:26:15 57 Jon Belcher M 27 1:26:12 28 1:26:43 107 Phil Bristow M 50 San Domenico 28 1:26:40 -

Llangattock Court Penpergwm • Abergavenny • Monmouthshire Llangattock Court Penpergwm • Aberga Venny Monmouthshire • NP7 9AR

Llangattock Court PENPERGWM • ABERGAVENNY • MONMOUTHSHIRE Llangattock Court PenPergwm • AbergA venny monmouthshire • nP7 9Ar Splendidly situated period house and cottage Hall • Sitting room • Dining room • Drawing room Kitchen • Utility rooms • 6 Bedrooms 2 Bathrooms en suite • 2 Showers (1 en suite) Study • Storerooms • Cellars Llangattock Cottage with Sitting room • Dining room Kitchen/Breakfast room • 2 Bedrooms • Bathroom Garaging • Outbuildings • Gardens In all about 1.6 acres Abergavenny 3 miles • raglan 6 miles monmouth 12 miles (All distances are approximate) These particulars are intended only as a guide and must not be relied upon as statements of fact. Your attention is drawn to the Important Notice on the last page of the text. Situation Llangattock Court is in the small hamlet of Penpergwm which lies within the Usk Valley a few miles to the south east of Abergavenny. Abergavenny has all the expected shops and amenities of an important market town including a well appointed Waitrose. Monmouth has the excellent Haberdashers schools. Closer by is a local store/post office in the Bryn, the famous Hardwick restaurant, and a thriving tennis club. The A40 provides fast access to the M50/M5, and the M4 and the national motorway network and the A465 Heads of the Valley makes the major centres in South Wales highly accessible. Abergavenny has a rail station with a quick link to Newport and from there on to London Paddington (2 hours). Abergavenny is known as the gateway to the Brecon Beacons and the Black Mountains. There are leisure centres, parks and a castle; the Brecon Beacons are close-by; numerous local golf courses include Abergavenny, Monmouth (Rolls) and Newport (Celtic Manor), the Brecon and Monmouthshire Canal flows nearby; and there are numerous walks and rides through the surrounding countryside. -

Wyedene, St Arvans

WYEDENE, ST ARVANS Local Independent Professional Wyedene, St Arvans, Chepstow, Monmouthshire NP16 6EZ AN ARCHITECT DESIGNED 5 BEDROOM DETACHED HOUSE, CONSTRUCTED TO A HIGH SPECIFICATION, IN THE SOUGHT-AFTER VILLAGE OF ST ARVANS •Reception Hall •Sitting Room •Dining Room •Study •Kitchen/Breakfast Room •Utility Room •Cloakroom •5 Bedrooms •3 En-Suites •Family Bathroom •Garage/Workshop •Off-Road Parking •Gardens •Underfloor Heating to Ground Floor •Hardwood Oak Doors •Cat 5 Wiring •Sought-after Village Location •Walking distance of village facilities Location: – St Arvans is an extremely popular village at the approach to the Wye Valley, being some 2.5 miles from the M48 motorway, which gives access eastbound over the Severn Bridge to the M4, M32 and M5 intersection, and westbound to Newport, Cardiff and South Wales. Chepstow town offers modern shopping facilities, primary and senior schools, regular bus & train services and leisure & health centres. Locally, the village offers a public house and restaurant, place of worship, shop and a garage. The Wye valley with its numerous country walks is ‘on the doorstep’ as well as the forestry commissioned own Chepstow Park. The Property:- An individually designed detached residence, built to exacting standards providing spacious family accommodation. Of conventional build with part rendered and part stone elevations under a slate roof. The ground floor is covered with a cut stone tiled floor, whilst the first floor, apart from the bathrooms has engineered oak flooring. The ground floor is warmed via individually zoned under flooring, oil fired heating, New Build – Architect Certificate – Built to High Specification – Internal Viewing Highly Recommended £550,000 Portwall House, Bank Street, Chepstow, Monmouthshire, NP16 5EL Tel: 01291 626775 www.newlandrennie.com Email: [email protected] The accommodation comprises, all dimensions approximate:- Cloakroom: Automatic lighting, low level w.c, marble wash Utility Room: Plumbing for washing machine. -

Black Mountains History

Black Mountains History Short pieces from the Llanthony History Group 2020 2 LV&DHG was formed in 2015 with seed corn funding from the Landmark Trust, as part its Heritage Lottery Funding for the restoration of Llwyn Celyn. We are a working group for people interested in the history of the Llanthony Valley, and the adjacent area of the Black Mountains in South Wales. The Group organises regular evening meetings in Cwmyoy Memorial Hall throughout the winter; and runs a series of historical walks and explorations for members in the summer. Committee 2020-21 Chairman: Douglas Wright Secretary: Pip Bevan Treasurer: Oliver Fairclough Events: Rosemary Russell Research: Pip Bevan Publications: Oliver Fairclough Publicity: Caroline Fairclough Members: Edith Davies Andrea Ellaway Colette Miles Judith Morgan Jenny Parry Rita Tait. Join the group at a meeting or walk, or contact Pip Bevan, the Secretary on 01873 890 609 or [email protected]. Individual membership is normally £7 a year (£4 to attend a single meeting). However, due to the uncertainties associated with the Covid-19 pandemic, there are no fees for the year from September 2020. http://www.llanthonyhistory.wales/ http://llanthonyhistory.genesis-ds.com/ 3 Contents 5. Oliver Fairclough Florence Attwood Mathews at Llanfihangel Court 9. Pip Bevan Snowed in: some memorable Black Mountains winters 13. Shirley Rippin Pen-y-Gadair Fawr - the Highest Forest in the UK. 16. Dick Vigers The Case of Jacob Watkins’ Will, 1861. 18. Caroline Fairclough Christine Olsen’s Photographs of the Llanthony Valley, 1950 – 55 4 Chair’s introduction This is the first collection of papers from the Llanthony History Group. -

Coridor-Yr-M4-O-Amgylch-Casnewydd

PROSIECT CORIDOR YR M4 O AMGYLCH CASNEWYDD THE M4 CORRIDOR AROUND NEWPORT PROJECT Malpas Llandifog/ Twneli Caerllion/ Caerleon Llandevaud B Brynglas/ 4 A 2 3 NCN 4 4 Newidiadau Arfaethedig i 6 9 6 Brynglas 44 7 Drefniant Mynediad/ A N tunnels C Proposed Access Changes 48 N Pontymister A 4 (! M4 C25/ J25 6 0m M4 C24/ J24 M4 C26/ J26 2 p h 4 h (! (! p 0 Llanfarthin/ Sir Fynwy/ / 0m 4 u A th 6 70 M4 Llanmartin Monmouthshire ar m Pr sb d ph Ex ese Gorsaf y Ty-Du/ do ifie isti nn ild ss h ng ol i Rogerstone A la p M4 'w A i'w ec 0m to ild Station ol R 7 Sain Silian/ be do nn be Re sba Saint-y-brid/ e to St. Julians cla rth res 4 ss u/ St Brides P M 6 Underwood ifi 9 ed 4 ng 5 Ardal Gadwraeth B M ti 4 Netherwent 4 is 5 x B Llanfihangel Rogiet/ 9 E 7 Tanbont 1 23 Llanfihangel Rogiet B4 'St Brides Road' Tanbont Conservation Area t/ Underbridge en Gwasanaethau 'Rockfield Lane' w ow Gorsaf Casnewydd/ Trosbont -G st Underbridge as p Traffordd/ I G he Newport Station C 4 'Knollbury Lane' o N Motorway T Overbridge N C nol/ C N Services M4 C23/ sen N Cyngor Dinas Casnewydd M48 Pre 4 Llanwern J23/ M48 48 Wilcrick sting M 45 Exi B42 Newport City Council Darperir troedffordd/llwybr beiciau ar hyd Newport Road/ M4 C27/ J27 M4 C23A/ J23A Llanfihangel Casnewydd/ Footpath/ Cycleway Provided Along Newport Road (! Gorsaf Pheilffordd Cyffordd Twnnel Hafren/ A (! 468 Ty-Du/ Parcio a Theithio Arfaethedig Trosbont Rogiet/ Severn Tunnel Junction Railway Station Newport B4245 Grorsaf Llanwern/ Trefesgob/ 'Newport Road' Rogiet Rogerstone 4 Proposed Llanwern Overbridge