Mining History of Mojave National Preserve

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Section 3.3 Geology Jan 09 02 ER Rev4

3.3 Geology and Soils 3.3.1 Introduction and Summary Table 3.3-1 summarizes the geology and soils impacts for the Proposed Project and alternatives. TABLE 3.3-1 Summary of Geology and Soils Impacts1 Alternative 2: 130 KAFY Proposed Project: On-farm Irrigation Alternative 3: 300 KAFY System 230 KAFY Alternative 4: All Conservation Alternative 1: Improvements All Conservation 300 KAFY Measures No Project Only Measures Fallowing Only LOWER COLORADO RIVER No impacts. Continuation of No impacts. No impacts. No impacts. existing conditions. IID WATER SERVICE AREA AND AAC GS-1: Soil erosion Continuation of A2-GS-1: Soil A3-GS-1: Soil A4-GS-1: Soil from construction existing conditions. erosion from erosion from erosion from of conservation construction of construction of fallowing: Less measures: Less conservation conservation than significant than significant measures: Less measures: Less impact with impact. than significant than significant mitigation. impact. impact. GS-2: Soil erosion Continuation of No impact. A3-GS-2: Soil No impact. from operation of existing conditions. erosion from conservation operation of measures: Less conservation than significant measures: Less impact. than significant impact. GS-3: Reduction Continuation of A2-GS-2: A3-GS-3: No impact. of soil erosion existing conditions. Reduction of soil Reduction of soil from reduction in erosion from erosion from irrigation: reduction in reduction in Beneficial impact. irrigation: irrigation: Beneficial impact. Beneficial impact. GS-4: Ground Continuation of A2-GS-3: Ground A3-GS-4: Ground No impact. acceleration and existing conditions. acceleration and acceleration and shaking: Less than shaking: Less than shaking: Less than significant impact. -

Westray Story a Predictable Path to Disaster

3 . // ^V7 / C‘H- The Westray Story A Predictable Path to Disaster Report of the Westray Mine Public Inquiry Justice K. Peter Richard, Commissioner Volume One November 1997 LIBRARY DEPARTfvtEr,T Or NATURAL RESOURCES. \ HALIFAX, NOVA SCOTIA \ ^V 2,2,4- VJ. I Published on the authority of the Lieutenant Governor in Council c, by the Westray Mine Public Inquiry. © Province of Nova Scotia 1997 ISBN 0-88871-465-3 Canadian Cataloguing in Publication Data Westray Mine Public Inquiry (N.S.) The Westray story: a predictable path to disaster Includes bibliographical references. Partial contents: v.[3] Reference - v.[4] Executive summary. ISBN 0-88871-465-3 (v.l) - 0-88871-466-1 (v.2) - 0-88871-467-X ([v.3])-0-88871-468-8 ([v.4]) 1. Westray Mine Disaster, Plymouth, Pictou, N.S., 1992. 2. Coal mine accidents—Nova Scotia—Plymouth (Pictou Co.) I. Richard, K. Peter, 1932- II. Title. TN806C22N6 1997 363.11’9622334'0971613 C97-966011-4 Cover: Sketch of Westray mine by Elizabeth Owen Permission is hereby given by the copyright holder for any person to reproduce this report or any part thereof. “The most important thing to come out of a mine is the miner.” Frederic Le Play (1806-1882) French sociologist and inspector general of mines of France » At 5:20 am on 9 May 1992 the Westray mine exploded taking the lives of the following 26 miners. John Thomas Bates, 56 Trevor Martin Jahn, 36 Larry Arthur Bell, 25 Laurence Elwyn James, 34 Bennie Joseph Benoit, 42 Eugene W. Johnson, 33 Wayne Michael Conway, 38 Stephen Paul Lilley, 40 Ferris Todd Dewan, 35 Michael Frederick MacKay, 38 Adonis J. -

Demography of Desert Mule Deer in Southeastern California

CALIFORNIA FISH AND GAME California Fish and Game 92(2):55-66 2006 DEMOGRAPHY OF DESERT MULE DEER IN SOUTHEASTERN CALIFORNIA JASON P. MARSHAL School of Natural Resources University of Arizona Tucson, AZ 85721 [email protected] LEON M. LESICKA Desert Wildlife Unlimited 4780 Highway 111 Brawley, CA 92227 VERNON C. BLEICH Sierra Nevada Bighorn Sheep Recovery Program California Department of Fish and Game 407 West Line Street Bishop, CA 93514 PAUL R. KRAUSMAN School of Natural Resources University of Arizona Tucson, AZ 85721 GERALD P. MULCAHY California Department of Fish and Game P. O. Box 2160 Blythe, CA 92226 NANCY G. ANDREW California Department of Fish and Game 78-078 Country Club Drive, Suite 109 Bermuda Dunes, CA 92201 Desert mule deer, Odocoileus hemionus eremicus, occur at low densities in the Sonoran Desert of southeastern California and consequently are difficult to monitor using standard wildlife techniques. We used radiocollared deer, remote photography at wildlife water developments (i.e., catchments), and mark-recapture techniques to estimate population abundance and sex and age ratios. Abundance estimates for 1999-2004 ranged from 40 to 106 deer, resulting in density estimates of 0.05-0.13 deer/km2. Ranges in herd composition were 41-74% (females), 6-31% (males), and 6-34% (young). There was a positive correlation (R = 0.73, P = 0.051) between abundance estimates and number of deer photographed/ catchment-day, and that relationship may be useful as an index of abundance in the absence of marked deer for mark-recapture methods. Because of the variable nature of desert wildlife populations, implementing 55 56 CALIFORNIA FISH AND GAME strategies that recognize that variability and conserving the habitat that allow populations to fluctuate naturally will be necessary for long-term conservation. -

NPCA Comments on Proposed Silurian

Stanford MillsLegalClinic Environmental Law Clinic Crown Quadrangle LawSchool 559 Nathan Abbott Way Stanford, CA 94305-8610 Tel 650 725-8571 Fax 650 723-4426 www.law.stanford.edu September 9, 2014 Via Electronic Mail and Federal Express James G. Kenna, State Director Bureau of Land Management California State Office 2800 Cottage Way, Suite W-1623 Sacramento, CA 95825 (916) 978-4400 [email protected] Katrina Symons Field Manager Bureau of Land Management Barstow Field Office 2601 Barstow Road Barstow, CA 92311 (760) 252-6004 [email protected] Dear State Director Kenna and Field Manager Symons: Enclosed please find comments by the National Parks Conservation Association (“NPCA”) on the solar and wind projects proposed by Iberdrola Renewables, Inc., in Silurian Valley, California. We understand that the U.S. Bureau of Land Management (“BLM”) is currently considering whether to grant the Silurian Valley Solar Project a variance under the October 2012 Record of Decision for Solar Energy Development in Six Southwestern States. We also understand that BLM is currently evaluating the Silurian Valley Wind Project under the National Environmental Policy Act. As the enclosed comments make clear, NPCA has serious concerns about the proposed projects’ compliance with applicable laws and policies, and about their potentially significant adverse effects on the Silurian Valley and surrounding region. We thank you for your consideration of these comments. NPCA looks forward to participating further in the administrative processes associated with the proposed projects. Respectfully submitted, Elizabeth Hook, Certified Law Student Community Law ❖ Criminal Defense ❖ Environmental Law ❖ Immigrants’ Rights ❖ International Human Rights and Conflict Resolution ❖ Juelsgaard Intellectual Property and Innovation ❖ Organizations and Transactions ❖ Religious Liberty ❖Supreme Court Litigation ❖ Youth and Education Law Project Mr. -

HUNTER INFORMATION SHEET DESERT BIGHORN Unit 266

HUNTER INFORMATION SHEET DESERT BIGHORN Unit 266 LOCATION: Unit 266 is situated in southern Clark County and comprises the northern portion of the Eldorado Mountains. ELEVATION: Elevations range from 656' at lake level (Lake Mohave) to 3,773' above Oak Creek Canyon. TERRAIN: Topographic features vary from rolling hills on the western margin of bighorn sheep habitat to the sheer, vertical cliffs characteristic of Black Canyon. VEGETATION: Vegetation is typical of the Mojave Desert=s creosote bush scrub community. Prominent vegetative types within this community include creosote and white bursage. LAND STATUS: The majority of the area that offers opportunities to hunt bighorn sheep lies within the Lake Mead National Recreation Area, and is administered by the National Park Service. A minor portion of bighorn sheep habitat is within the jurisdiction of the Bureau of Land Management, Las Vegas District. HUNTER ACCESS: Hunter access is considered good given the network of National Park Service approved roads. Some hunters opt to use boats to learn their area, and to access points which would otherwise be more difficult to reach on foot. Note: Please be aware that sections of this unit are in a wilderness area. Motorized equipment, mechanized transport, including wheeled game carriers and chainsaws, are prohibited in wilderness areas. Contact the Federal Management Agency responsible for this area for more information. MAP REFERENCE: Maps are available for purchase from BLM, or through private vendors such as Mercury Blueprint & Supply Co. (Las Vegas), Desert Outfitters (Las Vegas) or Oakman=s (Reno). At a minimum, hunters should possess the United States Geologic Survey, Boulder City 1:100,000-scale topographic map (30 x 60 minute quadrangle). -

Avalanche Information for Subscribers

InfoEx Industry Standard for an Extraordinary Industry InfoEx is a cooperative service managed by the Canadian Avalanche Association (CAA), providing a daily exchange of technical snow, weather and avalanche information for subscribers. Subscribers are individual CAA Professional Members, or organizations and commercial businesses (e.g. backcountry guiding companies, ski hills, BC Highways, Parks Canada) employing CAA Professional Members whose operations require actively managing avalanche hazards. InfoEx gives avalanche professionals access to data that is accurate, relevant and real time. This knowledge improves each subscriber’s awareness of the conditions, greatly enhancing their ability to manage their local avalanche risks. InfoEx also serves as one of the key sources of data used by Avalanche Canada’s (AC) and other organizations public avalanche forecasters to produce and verify their products. The value of the InfoEx contribution to the AC public avalanche bulletin is estimated at an excess of $2 million annually. The significance of this contribution by avalanche professionals and their employers to public avalanche safety in the mountains of Canada cannot be overstated. InfoEx Subscribers 2018-19 Downhill Ski Resorts KPOW! Fortress Mountain Dezaiko Lodge • Coast/Chilcotin Big White Ski Resort Catskiing Extremely Canadian • Columbia Castle Mountain Great Canadian Heli-Skiing Golden Alpine Holidays • Kootenay Pass Fernie Alpine Resort Gostlin Keefer Lake Lodge Hyland Backcountry Services • Kootenay Region Grouse Mountain Catskiing Ice Creek Lodge • North Cascades District Kicking Horse Mountain Resort Great Northern Snowcat Skiing Kokanee Glacier • Northwest Region Lake Louise Ski Resort Island Lake Lodge Kootenay Backcountry Guides Ningunsaw Marmot Basin K3 Cat Ski Kyle Rast • Northwest Region Terrace Mount Washington Alpine Resort Kingfisher Heliskiing Lake O’Hara Lodge Northwest Avalanche Solutions Norquay Last Frontier Heliskiing Mistaya Lodge Ltd. -

A History of Tailings1

A HISTORY OF MINERAL CONCENTRATION: A HISTORY OF TAILINGS1 by Timothy c. Richmond2 Abstract: The extraction of mineral values from the earth for beneficial use has been a human activity- since long before recorded history. Methodologies were little changed until the late 19th century. The nearly simultaneous developments of a method to produce steel of a uniform carbon content and the means to generate electrical power gave man the ability to process huge volumes of ores of ever decreasing purity. The tailings or waste products of mineral processing were traditionally discharged into adjacent streams, lakes, the sea or in piles on dry land. Their confinement apparently began in the early 20th century as a means for possible future mineral recovery, for the recycling of water in arid regions and/or in response to growing concerns for water pollution control. Additional Key Words: Mineral Beneficiation " ... for since Nature usually creates metals in an impure state, mixed with earth, stones, and solidified juices, it is necessary to separate most of these impurities from the ores as far as can be, and therefore I will now describe the methods by which the ores are sorted, broken with hammers, burnt, crushed with stamps, ground into powder, sifted, washed ..•. " Agricola, 1550 Introduction identifying mining wastes. It is frequently used mistakenly The term "tailings" is to identify all mineral wastes often misapplied when including the piles of waste rock located at the mouth of 1Presented at the 1.991. National mine shafts and adi ts, over- American. Society for Surface burden materials removed in Mining and Reclamation Meeting surface mining, wastes from in Durango, co, May 1.4-17, 1.991 concentrating activities and sometimes the wastes from 2Timothy c. -

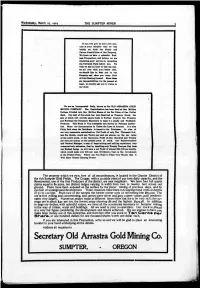

Secretary Old Arrastra Gold Mining Co

Wednesday, March 25, 1905 THE SUMPTER MINER &XWaMWWWMto t If you will plve us just n few min- i utes of your valuable timo we will briefly set forth the Merits and Future Possibilities of Our Property. We know we have a splendid Busi- ness Proposition, and believe we are rendering good service in spreading the Untinted Facts before you. We wish we had an hour to talk the mat- ter all over with you; better still, we should like to take you to our Property and show you every Foot of Gold Bearing Ground. Since these are impossibilities, for the present at least, we kindly ask you to listen to our story. We are an Incorporated Body, known as the OLD ARRA8TRA GOLD MINING COMPANY. The Capitalization has been fixed at One Million Dollars, Divided into One Million Shares of the Par Value of One Dollar Each. One half of this stock has been Reserved as Treasury Stock, the sale of whloh will provide ample funds to Further Exploit the Property and Purchase the Necessary Machinery to make it a steady and Profitable Producer. This Stock is and carries no Personal Liabili- ties. Since our Incorporation is Under the Laws of Arizona. It is also Fully Paid when the Certificate is Issued to the Purchaser. In view of our very reasonable capitalization, Net Profit of only Ten Thousand Dol- V lars Per Month, would pay Twelve per cent per annum, on the par value of the entire stock, or the Enormous Profit of .Ono Hundred and Twenty per cent per annum on the present price of Btock. -

CP's North American Rail

2020_CP_NetworkMap_Large_Front_1.6_Final_LowRes.pdf 1 6/5/2020 8:24:47 AM 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 Lake CP Railway Mileage Between Cities Rail Industry Index Legend Athabasca AGR Alabama & Gulf Coast Railway ETR Essex Terminal Railway MNRR Minnesota Commercial Railway TCWR Twin Cities & Western Railroad CP Average scale y y y a AMTK Amtrak EXO EXO MRL Montana Rail Link Inc TPLC Toronto Port Lands Company t t y i i er e C on C r v APD Albany Port Railroad FEC Florida East Coast Railway NBR Northern & Bergen Railroad TPW Toledo, Peoria & Western Railway t oon y o ork éal t y t r 0 100 200 300 km r er Y a n t APM Montreal Port Authority FLR Fife Lake Railway NBSR New Brunswick Southern Railway TRR Torch River Rail CP trackage, haulage and commercial rights oit ago r k tland c ding on xico w r r r uébec innipeg Fort Nelson é APNC Appanoose County Community Railroad FMR Forty Mile Railroad NCR Nipissing Central Railway UP Union Pacic e ansas hi alga ancou egina as o dmon hunder B o o Q Det E F K M Minneapolis Mon Mont N Alba Buffalo C C P R Saint John S T T V W APR Alberta Prairie Railway Excursions GEXR Goderich-Exeter Railway NECR New England Central Railroad VAEX Vale Railway CP principal shortline connections Albany 689 2622 1092 792 2636 2702 1574 3518 1517 2965 234 147 3528 412 2150 691 2272 1373 552 3253 1792 BCR The British Columbia Railway Company GFR Grand Forks Railway NJT New Jersey Transit Rail Operations VIA Via Rail A BCRY Barrie-Collingwood Railway GJR Guelph Junction Railway NLR Northern Light Rail VTR -

Strategic Long-Range Transportation Plan for the Colorado River Indian

2014 Strategic Long Range Transportation Plan for the Colorado River Indian Tribes Final Report Prepared by: Prepared for: COLORADO RIVER INDIAN TRIBES APRIL 2014 Project Management Team Arizona Department of Transportation Colorado River Indian Tribes 206 S. 17th Ave. 26600 Mohave Road Mail Drop: 310B Parker, Arizona 85344 Phoenix, AZ 85007 Don Sneed, ADOT Project Manager Greg Fisher, Tribal Project Manager Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] Telephone: 602-712-6736 Telephone: (928) 669-1358 Mobile: (928) 515-9241 Tony Staffaroni, ADOT Community Relations Project Manager Email: [email protected] Phone: (602) 245-4051 Project Consultant Team Kimley-Horn and Associates, Inc. 333 East Wetmore Road, Suite 280 Tucson, AZ 85705 Mary Rodin, AICP Email: [email protected] Telephone: 520-352-8626 Mobile: 520-256-9832 Field Data Services of Arizona, Inc. 21636 N. Dietz Drive Maricopa, Arizona 85138 Sharon Morris, President Email: [email protected] Telephone: 520-316-6745 This report has been funded in part through financial assistance from the Federal Highway Administration, U.S. Department of Transportation. The contents of this report reflect the views of the authors, who are responsible for the facts and the accuracy of the data, and for the use or adaptation of previously published material, presented herein. The contents do not necessarily reflect the official views or policies of the Arizona Department of Transportation or the Federal Highway Administration, U.S. Department of Transportation. This report does not constitute a standard, specification, or regulation. Trade or manufacturers’ names that may appear herein are cited only because they are considered essential to the objectives of the report. -

Soda Springs, a Small San Bernardino County Desert Oasis, Eight Miles South of Interstate 15 and Baker, Between Barstow And

Volume XX, 1980 SODA SPRINGS, SAN BERNARDINO COUNTY: SEQUENTIAL LAND USE Stephen T. Glass* Soda Springs, a small San Bernardino County desert oasis, eight miles south of Interstate 15 and Baker, between Barstow and Las Vegas, goes unnoticed by the thousands of travelers that pass daily through the Mohave Desert by car, bus, or train. (Fig. 1) Little rem:ains to indicate Soda Spring's former importance to the region's development. Only faint remnants of the former Mojave Road and the Tonopah and Tidewater Railroad are noticeable to the perspicacious rock climber or air traveler. The historical succession of land uses in Soda Springs has recently been continued by the addition of the Desert Research Center, under the auspices of the California State University and Coliege System. Before European Settlement Soda Spring's strategic location in the eastern Mojave has had a major effect on the commerce and, as importantly, on human survival in the region. Before the advent of European explorers, ancient trade trails led some 283 miles from the Mojave Valley on the Colorado River to the Pacific Coast. The nomadic Mojave Indians maintained a large permanent village north of present day Needles. Acting as middle-men *Mr. Glass is Head, Office of Noise Control, Environmental Health Division, City of Long Beach. 10 T \ ..\ (�.�� Yt ";; t�.J� Ei9-:>-. /">�:��- K.'f!l�" .. ; .. - ·· . • �.t '•',, ,;:..:.\ .... .. � . (, .... ... • .. -�� ;f .. ,. .. , .":' ···' . : . ..(\ ' 0 . i k . .. -�,. r.·�·) . u_::?r��(�:}.. ts?�. } " :)�). ::/ ;"''\ . , · '*SoliS't ; ' \,_..""'••' • I /J� _,,,-.,- �--<>:>l . .' i •••••' •• • .. � .. \ ; . ( " ..·· • ..,,_ .,.,., ·-�v :. - .,«, TBI.OJIIIIOD .... ··. ' •J . �r(-·r: )·,' r'i;-·-!.{ ' , ., AND OTHER EARLY WAGON ROADS (y' (::./ OF THE ���� �;_...� ��: ,��r . -

Frontier West” Mining

“The Frontier West” Mining • Many Americans were lured to the West by the chance to strike it rich mining gold and silver. • The western mining boom had begun with the California Gold Rush of 1849. • From California miners spread out in search of new strikes. Comstock Lode • 1859 – Gold was discovered in the Sierra Nevada. • Henry Comstock = “Comstock Lode” • Unknown to its owners, Comstock Lode was even richer in another precious metal. “danged blue stuff” • Miners at Comstock Lode complained about the heavy Blue sand that was mixed in with the gold. • Some curious miners had the “danged blue stuff” taken to California to be tested. • Tests showed that the sand was loaded with silver! Boom Towns • The Comstock Lode attracted thousands of people to the West. • The mining camp grew into the “boom town” – a town that experiences sudden growth and economic success) of Virginia City, Nevada. • Miners eventually moved into other areas such as Montana, Idaho, Colorado, and South Dakota. “Ghost Towns” • Towns grew up near all the major mining sites. Mines lasted only a few years, When the ore was gone, boom towns” turned into “ghost towns”. • Other settlements lasted and grew. Denver and Colorado Springs grew up near rich gold mines. • The surge of miners into the West created some problems: – Miners and towns polluted clear mountain streams, – Miners cut down forests to get wood for buildings, and – Miners forced Native Americans from their lands. •A few miners got “rich” quick – most did not! Railroads • Railroad Companies raced to law down track to the mines. • The federal government encouraged railroad building in the West by loaning money to the railroad companies.