Edwin Link 0 Mi E ,S

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Atlas of the Ornamental and Building Stones of Volubilis Ancient Site (Morocco) Final Report

Atlas of the ornamental and building stones of Volubilis ancient site (Morocco) Final report BRGM/RP-55539-FR July, 2008 Atlas of the ornamental and building stones of Volubilis ancient site (Morocco) Final report BRGM/RP-55539-FR July, 2008 Study carried out in the framework of MEDISTONE project (European Commission supported research program FP6-2003- INCO-MPC-2 / Contract n°15245) D. Dessandier With the collaboration (in alphabetical order) of F. Antonelli, R. Bouzidi, M. El Rhoddani, S. Kamel, L. Lazzarini, L. Leroux and M. Varti-Matarangas Checked by: Approved by: Name: Jean FERAUD Name: Marc AUDIBERT Date: 03 September 2008 Date: 19 September 2008 If the present report has not been signed in its digital form, a signed original of this document will be available at the information and documentation Unit (STI). BRGM’s quality management system is certified ISO 9001:2000 by AFAQ. IM 003 ANG – April 05 Keywords: Morocco, Volubilis, ancient site, ornamental stones, building stones, identification, provenance, quarries. In bibliography, this report should be cited as follows: D. Dessandier with the collaboration (in alphabetical order) of F. Antonelli, R. Bouzidi, M. El Rhoddani, S. Kamel, L. Lazzarini, L. Leroux and M. Varti-Matarangas (2008) – Atlas of the ornamental and building stones of Volubilis ancient site (Morocco). BRGM/RP-55539-FR, 166 p., 135 fig., 28 tab., 3 app. © BRGM, 2008. No part of this document may be reproduced without the prior permission of BRGM. Atlas of the ornamental and building stones of Volubilis Synopsis The present study titled “Atlas of the ornamental and building stones of Volubilis” was performed in the framework of the project MEDISTONE (“Preservation of ancient MEDIterranean sites in terms of their ornamental and building STONE: from determining stone provenance to proposing conservation/restoration techniques”) supported by the European Commission (research program FP6-2003-INCO-MPC-2 / Contract n° 015245). -

What Was Life Like in Roman London? Londinium (Roman London) Was Founded in About AD50 and Soon Became the Centre of Administration for the Province of Britannia

What was life like in Roman London? Londinium (Roman London) was founded in about AD50 and soon became the centre of administration for the province of Britannia. The population was a mix of civilians, families, soldiers, sailors, workers and slaves. Many of them were from all parts of the Roman Empire, but the majority were native Britons. Daily life in Roman London was hard. Most Roman Londoners had to work long hours to make a living, rising at dawn and stopping only for a lunchtime snack. They worked a seven-day week, but there were numerous festivals and feast days in honour of the gods, which enabled them to have a break. So, although the workers lived and worked in small cramped houses and workshops, they also knew how to enjoy themselves and would go to the baths and taverns or seek entertainment at the amphitheatre. Roman London was finally abandoned in AD410. Who lived in Roman London? Roman London was a cultural melting pot. Officials were sent from every corner of the Roman Empire to help run the new province of Britannia. Administrators, merchants, soldiers, retired soldiers and specialised craft workers were needed. They would have brought their households along with them. Excavations of Roman cemeteries show that the town was overwhelmingly populated by civilians rather than soldiers. The majority were probably native Britons drawn to the new town, hopeful of making their fortunes as labourers, craft workers and shopkeepers. As well as fresh food, the busy population needed clothes, shoes, pottery and tools, all of which were made locally. -

The Beggar of Volubilis (Roman Mysteries, Book 14) by Caroline Lawrence

THE BEGGAR OF VOLUBILIS PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Caroline Lawrence,Andrew Davidson | 272 pages | 01 Nov 2009 | Hachette Children's Group | 9781842556047 | English | London, United Kingdom The Beggar of Volubilis (Roman Mysteries, book 14) by Caroline Lawrence Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. Main article: Roman Mysteries TV series. The Roman Mysteries by Caroline Lawrence. Roman Mysteries. Hidden categories: Articles needing additional references from July All articles needing additional references Use dmy dates from July All articles with unsourced statements Articles with unsourced statements from July Namespaces Article Talk. Views Read Edit View history. Help Learn to edit Community portal Recent changes Upload file. Download as PDF Printable version. In Volubilis they find both Gaius and the emerald, but it is not as easy to take them back to Italy as they had supposed. During the adventure, they meet a woman who claims to be descended from Cleopatra and a man who could be the late emperor Nero. Sign In Don't have an account? Start a Wiki. It is published by Orion Books. This article is a stub. Community Reviews. Showing Average rating 3. Rating details. More filters. Sort order. Jun 01, Guo added it. I didn't notice this when I first read this book as a child, but a few years later I realized this book contains several tropes with regards to travelling to that region Local chieftain has several wives, and wive number 4 is only 9 years old. Heads get chopped off, no questions asked. But there is always a downside. People in some far-flung corner of the empire do not realize that the prev I didn't notice this when I first read this book as a child, but a few years later I realized this book contains several tropes with regards to travelling to that region People in some far-flung corner of the empire do not realize that the previous emperor has died and someone has replaced him. -

Guildhall Yard, Art Gallery and Amphitheatre: Consider Archaeology and the Amphitheatre in the Guildhall Yard

KS2 Romans 4 Roman amphitheatre and museum dual visit don 201 Partnership with Guildhall Art Gallery © Museum Lon of Contents National Curriculum links and session description 1 Timetable 2 Practical guidelines 3 Museum of London gallery plan 4 Teachers notes on Roman London gallery 5 Risk assessment advice for teachers 6 Walking trail 7 - 12 Pre-visit activities 13 Follow-up activities 14 Planning your journey 15 In addition, please see Amphitheatre activity sheets. (Please make enough copies before your visit, you may also like to use activity sheets for the Museum of London gallery visit.) © Museum of London 2014 Curriculum links your amphitheatre session. We offer a selection of activity sheets that can be KS2 History used in the Roman London gallery. Roman London gallery activity sheets Designed to support Key Stage 2 History are offered in word format so that study of Roman settlement in Britain. teachers can adapt them to the needs of This session explores Londinium, its their own class. architecture and people, focusing on two important aspects of Roman life; the Walking Trail. army and entertainment at the amphitheatre. Using evidence from a The 30 minute walk between the two variety of sources (including the Museum sites, should be used to examine the of London’s extensive collection of topography of Londinium, including Roman artefacts and the impressive seeing the remains of the Roman wall remains of London’s Roman and comparing different aspects of life in Amphitheatre preserved beneath the the city now and then. When possible Guildhall Art Gallery,) pupils will develop museum staff will support this walk, but historical enquiry skills and learn how please be prepared to lead the walk archaeology helps us to interpret the yourself. -

Londinium: the History of the Ancient Roman City That Became London Pdf

FREE LONDINIUM: THE HISTORY OF THE ANCIENT ROMAN CITY THAT BECAME LONDON PDF Charles River Editors | 48 pages | 23 Apr 2015 | Createspace | 9781511855679 | English | United States Era by Era Timeline of Ancient Roman History Preceding the period of the Roman kingsduring the Bronze AgeGreek cultures came into contact with Italic ones. By the Iron Age, there were huts in Rome; Etruscans were extending their civilization into Campania; Greek cities had sent colonists to the Italic Peninsula. Londinium: The History of the Ancient Roman City That Became London Roman history Londinium: The History of the Ancient Roman City That Became London for more than a millennium, during which the government changed substantially from kings to Republic to Londinium: The History of the Ancient Roman City That Became London. This timeline shows these major divisions over time and the defining features of each, with links to further timelines showing the key events in each period. The central period of Roman history runs from about the second century B. In the legendary period, there were 7 kings of Rome, some Roman, but others Sabine or Etruscan. Not only did the cultures mingle, but they started to compete for territory and alliances. Rome expanded, extending to about square miles during this period, but the Romans didn't care for their monarchs and got rid of them. The Roman Republic began after the Romans deposed their last king, in about B. This Republican period lasted about years. After about B. The early period of the Roman Republic was all about expanding and building Rome into a world power to be reckoned with. -

Timetravelrome Guide

The Roman London Short Guide to Roman Sites in London . Mithraeum . Amphitheater . Town Defenses This free guide is offered to you by Timetravelrome - a Mobile App that finds and describes every significant ancient Roman city, fortress, theatre, or sanctuary in Europe, Middle East as well as across North Africa. www.timetravelrome.com TimeTravelRome Index Monuments Page Star Ranking Short History of London 3 Mithraeum 4 London Amphitheatre 5 Town Defences and Tower Hill Wall 6 Coopers Row City Wall 7 Noble Street City Wall 7 Cripplegate Fort West Gate 8 Bastion 14 8 Giltspur Street City Walls 9 St Alphage's Garden City Wall 9 Sources 10 2 Roman London || 2000 Years of History 3 Short History of London London was first founded by the Romans nearly 2000 By the early 400s AD, instability throughout the Roman years ago. The Roman’s called their new settlement Empire as well as Saxon aggression was making Roman Londinium. The etymology of this name is uncertain but rule in Britain increasingly untenable and in 410 AD one possible explanation states that it is derived from the orders were received from Rome to withdraw from the Indo-European word plowonida (in Brythonic this would province. The complete breakdown of Roman have been lowonidonjon) meaning ‘fast-flowing river. governance, economics and trade in the years The location of the settlement was chosen for its immediately following 410 AD greatly exacerbated this strategic position along the banks of the river Thames at and the majority of Roman towns and cities within the the first point the river could safely be bridged. -

Boudicca's Rebellion Against the Roman Empire in 60 AD Daniel Cohen Union College - Schenectady, NY

Union College Union | Digital Works Honors Theses Student Work 6-2016 Boudicca's Rebellion Against the Roman Empire in 60 AD Daniel Cohen Union College - Schenectady, NY Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalworks.union.edu/theses Part of the Ancient History, Greek and Roman through Late Antiquity Commons, Celtic Studies Commons, European History Commons, and the Military History Commons Recommended Citation Cohen, Daniel, "Boudicca's Rebellion Against the Roman Empire in 60 AD" (2016). Honors Theses. 135. https://digitalworks.union.edu/theses/135 This Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Work at Union | Digital Works. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of Union | Digital Works. For more information, please contact [email protected]. i Boudicca’s Rebellion Against the Roman Empire in 60 AD By Daniel Cohen ********* Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for Honors in the Department of History UNION COLLEGE June, 2016 ii ABSTRACT Cohen, Daniel Boudicca’s Rebellion Against the Roman Empire in 60 AD This paper examines the rebellion of Boudicca, the queen of the Iceni tribe, during the Roman Empire’s occupation of Britannia in 60 AD. The study shows that had Boudicca not changed her winning strategy in one key battle, she could have forced the Roman Empire to withdraw their presence from Britannia, at least until it was prudent to invade again. This paper analyzes the few extant historical accounts available on Boudicca, namely those of the Roman historians Tacitus and Cassius Dio, to explore the effectiveness of tactics on both sides of the rebellion. -

The Beggar of Volubilis Free

FREE THE BEGGAR OF VOLUBILIS PDF Caroline Lawrence,Andrew Davidson | 272 pages | 01 Nov 2009 | Hachette Children's Group | 9781842556047 | English | London, United Kingdom The Beggar of Volubilis by Caroline Lawrence Become a member to get exclusive early access to our latest reviews too! Browse our magazines. Submit your novel for review. Our features are original articles from our print magazines these will say where they were originally published or original articles commissioned for this The Beggar of Volubilis. It is also where our staff first look for news and features for the site. Our membership is worldwide, but we still like to meet up - and many members travel thousands of miles to do so. Here you can find out about our conferences and chapter meetings, and can check the important dates for our Awards and magazine. March, 81 AD. According to prophecy, whoever possesses it will rule Rome — and rumours abound that the dead Emperor Nero is very much alive. Can they find him and persuade him to come home? But when they arrive in Sabratha, disaster strikes. The ship, which was to have taken them on to Volubilis, sails without them — taking all their belongings. Somehow, they must travel several thousand miles with no money. They join a pantomime troupe and begin the long trek across the desert —a place full of dangers from slave traders, sandstorms, thirst and mirages. This is an adventure story, set in Africa in AD The descriptions are very good, and like the rest of the series, it has an excellent plot which, at points, is very dramatic. -

1 30 AD • Jesus Death, Resurrection, Ascension • Day of Pentecost In

30 AD • Jesus Death, Resurrection, Ascension • Day of Pentecost in Acts 2 31 AD • Peter heals crippled man in temple. (Acts 3) • Peter and John arrested by Sanhedrin. (Acts 4:1-3) 32 AD • Joseph, a Levite from Cyprus (Barnabas) sells a field. (Acts 4:36-37) • Ananias and Sapphira die. • The Jerusalem church meets by the temple in Solomon’s Colonnade (Porch). (Acts 5:12) • Apostles perform many miracles. • Apostles arrested but released by angel. 33 AD • Seven deacons chosen (Acts 6:1-6) • Church is growing rapidly. (Acts 6:7) • A large number of priests believe. (Acts 6:7) 34 AD • Saul arrives in Jerusalem. • Stephen debates Jews coming from Cyrene, Cilicia (ie. Saul), and Alexandria. (Acts 6:9) • Stephen arrested by Sandhedrin. (Acts 6:12) • Stephen stoned (Acts 7:59) • Saul persecutes the church in Jerusalem. • Philip goes to Samaria. (Acts 8:5) • Philip meets Ethiopian Treasurer. (Acts 8:26-27) 35 AD • Saul converted on road to Damascus. (Acts 9) • Saul is in Damascus. • Saul leaves for Arabia. (Gal.1:17) 36 AD • Saul is in Arabia. 37 AD • Saul is in Arabia. Caligula is emperor 1 38 • Saul returns to preach in Damascus. • Saul’s life is threatened. (Acts 9:23) • Saul escapes to Jerusalem. • Barnabas introduces Saul to disciples. • Saul stays with Peter 15 days. (Gal.1:18-19) • Saul debates Grecian Jews. (Acts 9:29) • Saul flees to Tarsus in Cilicia. (Acts 9:29,30) 39 • Saul preaches in Cilicia and Syria for five years. (Referred to during Gal.1:21-22) • Persecution has ceased in Jerusalem. -

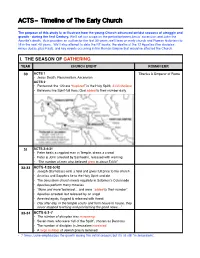

WBW | P.2 | Timeline of Acts | Notes

ACTS- Timeline of The Early Church The purpose of this study is to illustrate how the young Church advanced amidst seasons of struggle and growth - during the first Century. We’ll set our scope on the period between Jesus’ ascension and John the Apostle’s death. Acts provides an outline for the first 30 years; we’ll lean on early church and Roman historians to fill in the next 40 years. We’ll also attempt to date the NT books, the deaths of the 12 Apostles (the disciples minus Judas, plus Paul), and key events occurring in the Roman Empire that would’ve affected the Church. I. THE SEASON OF GATHERING YEAR CHURCH EVENT ROMAN EMP. 30 ACTS 1 Tiberius is Emperor of Rome • Jesus Death, Resurrection, Ascension ACTS 2 • Pentecost: the 120 are “baptized” in the Holy Spirit; 3,000 believe • Believers live Spirit-full lives; God added to their number daily 31 ACTS 3-4:31 • Peter heals a crippled man in Temple, draws a crowd • Peter & John arrested by Sanhedrin, released with warning • “The number of men who believed grew to about 5,000” 32-33 ACTS 4:32-5:42 • Joseph (Barnabas) sells a field and gives full price to the church • Ananias and Sapphira lie to the Holy Spirit and die • The Jerusalem church meets regularly in Solomon’s Colonnade • Apostles perform many miracles • “More and more” believed… and were “added to their number” • Apostles arrested, but released by an angel • Arrested again, flogged & released with threat • Day after day, in the temple courts and from house to house, they never stopped teaching and proclaiming the good news…” 33-34 ACTS 6:1-7 • The number of disciples was increasing • Seven men, who were “full of the Spirit”, chosen as Deacons • The number of disciples in Jerusalem increased • A large number of Jewish priests believed • 7 times, Luke emphasizes the growth during this initial season; but it’s all still “in Jerusalem”. -

Roman London

III Roman London Ralph Merrifield The Origin of Londinium were unfamiliar with the ford they were obliged to swim, but some others got over by a bridge a little way upstream.4 It BRIDGE-BCILDI:--:G \vas a particular accomplishment of seems likely that this was a temporary military bridge hastily Roman military engineers, and the main roads that were soon thrown across the river by an army that had come prepared to to be centred on the first London Bridge were almost deal with this obstacle. Ifso, it is likely to have been a floating certainly laid out by the sun'eyors of the Roman army bridge, and it was not necessarily on the same site as the later primarily for a military purpose the subjugation and control permanent bridge, which was presumably a piled structure. of the new province. It was the army therefore that provided Recent work in Southwark suggests that the south bank the conditions from \\'hich London was born. Can \ve go opposite the Roman city was by no means an obvious place to further, and suggest that Londinium itself was a creation of select as a bridgehead. It is true that sandy gravels here rose a the Roman arm\) A.. centre of land communications that fnv feet above the less stable silts on either side, but they were could also be reached b\' large sea-going ships, taking intersected by creeks and river-channels, forming a series of advantage of the tides that probabh' then just reached the islets \vhich themselves had to be linked by small bridges. -

Roman Legionary Fortresses and the Cities of Modern Europe Author(S): Thomas H

Roman Legionary Fortresses and the Cities of Modern Europe Author(s): Thomas H. Watkins Source: Military Affairs, Vol. 47, No. 1 (Feb., 1983), pp. 15-25 Published by: Society for Military History Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/1987828 . Accessed: 09/05/2011 18:10 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at . http://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=smh. Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Society for Military History is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Military Affairs. http://www.jstor.org RomanLegionciry fortresses aond the Ctiesof ModernEurope by Thomas H. Watkins Western Illinois University England the natives to take up city life.