Mythic Structure Theory: Proposing a New Framework for the Study of Political Issues David L

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Discussion Questions for the Power of Myth by Joseph Campbell and Bill Moyers

Discussion Questions for The Power of Myth by Joseph Campbell and Bill Moyers 1. Campbell defines myth in various ways in the book, including: a. A way to experience life b. A clue to the spiritual potential of human beings c. The song of the imagination d. The reconciliation of the conditions of life, that is, that life is about the killing of other organisms e. The one grand story of humankind f. Myth affirms that there is an invisible plane which supports the visible plane g. Myth teaches us when to let go h. A fairy tale is a child’s myth Do you agree with Campbell’s various definitions of myth? Do you have a different definition of myth? Is there one definition that seems more apt than others? 2. Campbell claims that there are two different kinds of myths: a. A portion that relates to nature and man’s place in nature b. A portion that is sociological, that is, how men fit into their society Do you agree with Campbell that there are two types of myth? Are there other types of myths? Are there myths which do not fit into one of these two categories; if so, which ones? 3. The hero, according to Campbell is a: a. Person who faces trial and tribulations as a result of bringing new possibilities into the field of interpreted experience b. Lives in the field of time and must make decisions about good and evil c. An artist who helps develop and communicate myths today (he cites James Joyce as an artist who develops modern myths) d. -

The Stages of the Hero's Journey All Stories Consist of Common Structural Elements of Stages Found Universally in Myths, Fairy Tales, Dreams, and Movies

Excepts from Myth and the Movies, Stuart Voytilla1 Foreword By Christopher Vogler … Among students of myth like Carl Jung, Mircea Eliade, Theodore Gaster, and Heinrich Zimmer, the work of a man named Joseph Campbell has particular relevance for our quest. He hammered out a mighty link of the chain, a set of observations known as The Hero’s Journey. In books like The Hero with a Thousand Faces, The Power of Myth, and The Inner Reaches of Outer Space, Campbell reported on the synthesis he found while comparing the myths and legends of many cultures. The Hero’s Journey was his all-embracing metaphor for the deep inner journey of transformation that heroes in every time and place seem to share, a path that leads them through great movements of separation, descent, ordeal, and return. In reaction to Campbell’s work, a man named George Lucas composed what many have called a myth for our times - the Star War series, in which young heroes of a highly technological civilization confront the same demons, trials, and wonders as the heroes of old. ... The Stages of the Hero's Journey All stories consist of common structural elements of Stages found universally in myths, fairy tales, dreams, and movies. These twelve Stages compose the Hero's Journey. What follows is a simple overview of each Stage, illustrating basic characteristics and functions. Use it as a quick-reference guide as you explore the genre and movie analyses. Since it cannot provide all of Christopher Vogler's insights upon which it was based, I recommend you refer to his book, The Writer's Journey, for a much more thorough evaluation. -

102 the Message of the Myth

File Name: Sequence 1-IPF-JC-102 Transcriber I-Source QA/QC Comments Length of file: 00:56:28 Audio Category List volume, accent, background noise, ESL speakers. Any Comments [e. G. times of recording not needing transcription, accents, etc. ] Any Problems with Recording [e. g. background noise, static, etc] Unusual Words or Terms: Must be completed [E. g. Abbreviations, Company Names, Names of people or places, technical jargon] Number of Speakers: 2 The Message of the Myth Page#1 Moyers: Genesis 1; in the beginning God created the heavens and the earth, the earth was without form and void and darkness was upon the face of the deep. Joseph Campbell: This is the song of the world from legend of the Pima Indians. In the beginning, there was only darkness everywhere, darkness and water. And the darkness gathered thick in places crowding together, and then separating, crowding, and separating. Moyers: And the spirit of God [00:01:00] was moving over the face of the waters and God said let there be light. Joseph Campbell: This is from the Hindu Upanishad. In the beginning there was only the great self reflected in the form of a person reflecting it found nothing about itself then its first word was this am I. Moyers: Joseph Campbell was [00:02:00] nine years old when his father took him to the American Museum of natural history here in New York City, the totem poles and masks mesmerized him, who made them he wondered and why, what did they mean. The little boy who began to read everything he could about Indians went on to become a foremost teacher and interpreter of mythology. -

{Download PDF} the Power of Myth Ebook, Epub

THE POWER OF MYTH PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Joseph Campbell,Bill Moyers | 236 pages | 20 Sep 1989 | Bantam Doubleday Dell Publishing Group Inc | 9780385247740 | English | New York, United States The Power of Myth PDF Book Campbell jumps from one myth to another; dwelling in the fact of its existence and never going beyond to study its meaning, relevance, depth, or "power," making his bias towards Buddhism unblushingly obvious and un Professor Campell leaves the reader wanting a more profound insight regarding the human person's social, anthropological, and religious need for myth; instead we are left with, well, to use one of his anecdotes: "We don't have a Philosophy, or a Theology Comments and questions about our policy are welcome. Well, you see, this thing communicates. Refresh and try again. His answer is that we create our own meaning in the world. Joseph Campbell. If you want to get to know Campbell's ideas, there are better works - especially "Hero with a Thousand Faces" and the four-volume "Masks of God" - to read, but this series of interviews, which one can also watch on video, remains a good introduction to his worldview and approach, and had a big impact on me when I first encountered it in my 20s. Feb 29, Jason Koivu rated it it was amazing Shelves: fiction , non-fiction , history , fantasy , psychology-philosophy. I don't wanna get dramatic in a Goodreads review. A preeminent scholar, writer, and teacher, he has had a profound influence on millions of people. Contemporary rituals are carried out to mark special events in private lives, such as an individual's marriage or enlistment in a branch of the armed forces and, on public occasions such as the inauguration of civil and national leaders. -

Joseph Campbell

The Power of Myth (Anchor Edition, 1991) by Joseph Campbell with Bill Moyers a.b.e- book v3.0 / Notes at EOF FIRST ANCHOR BOOKS EDITION, JULY 1991 Copyright© 1988 by ApostropheS Productions, Inc., and Alfred van der Marck Editions All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. Published in the United States by Anchor Books, a division of Random House, Inc., New York, and simultaneously in Canada by Random House of Canada Limited, Toronto. The fully illustrated edition of The Power of Myth was originally published in both hardcover and paperback by Doubleday in 1988. The Anchor Books edition is published by arrangement with Doubleday. ANCHOR BOOKS and colophon are registered trademarks of Random House, Inc. Grateful acknowledgment is made to Barnes & Noble Books, Totowa, New Jersey, for permission to quote from "The Second Coming" by William Butler Yeats. Campbell, Joseph, 1904- The power of myth / Joseph Campbell, with Bill Moyers; Betty Sue Flowers, editor. -- 1st Anchor Books ed. p. cm. 1. Myth. 2. Campbell, Joseph, 1904- -- Interviews. 3. Religion historians -- United States -- Interviews. I. Moyers, Bill D. II. Flowers, Betty S. III. Title. [BL304.C36 1990] 90-23860 291.1'3 -- dc20 CIP ISBN 0-385-41886-8 www.anchorbooks.com PRINTED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA 26 25 24 23 2221 20 19 18 To Judith, who has long heard the music Contents Editor's Note Introduction by Bill Moyers I Myth and the Modern World II The Journey Inward III The First Storytellers IV Sacrifice and Bliss V The Hero's Adventure VI The Gift of the Goddess VII Tales of Love and Marriage VIII Masks of Eternity Editor's Note This conversation between Bill Moyers and Joseph Campbell took place in 1985 and 1986 at George Lucas' Skywalker Ranch and later at the Museum of Natural History in New York. -

The Power of Mythic Journeys Comes to Atlanta in June 2004

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE: March 1, 2004 MEDIA CONTACTS: Anya Martin (678) 468-3867 Dawn Zarimba Edelman Public Relations (404) 262-3000 [email protected] THE POWER OF MYTHIC JOURNEYS COMES TO ATLANTA IN JUNE 2004 James Hillman, Janis Ian and Joyce Carol Oates are among more than 140 participants at conference and performance festival celebrating Joseph Campbell Centennial ATLANTA, GA – The first annual Mythic Journeys will bring together more than 140 of the world’s leading scholars, psychologists, educators, business leaders, artists, authors, filmmakers and performers for an unprecedented dialogue on the importance of storytelling and imagination in contemporary life from June 3-6, 2004, at the Atlanta Hyatt Regency Hotel. James Hillman, the father of archetypal psychology, has called the event the first-ever “spiritual Spoleto” festival. Merging roundtable conversations and workshops with a multicultural art exhibit, marketplace and theatrical, music and dance performances, the event will both honor and continue the discourse started by Joseph Campbell (1904-1987), the great authority on mythology. Program participants include Hillman, Sam Keen (co-producer of award-winning PBS documentary “Faces of the Enemy”), African spiritual teacher and author Sobonfu Somé, anthropologist Alan Dundes, Scott Livengood (President/CEO, Krispy Kreme), Joey Reiman (CEO, BrightHouse, the world’s first ideation company), and pioneering Jungian analysts Marion Woodman, Jean Shinoda Bolen and Michael Vannoy Adams. -more- Mythic Journeys/Page 2 Artist and performance guests include Grammy Award-winning singer/songwriter Janis Ian, artists Brian Froud (ªFaeriesº) and Alan Lee (conceptual artist for the Oscar-winning ªLord of the Ringsº film trilogy), poet/essayist Robert Bly (ªIron Johnº), poet/translator Coleman Barks (ªThe Essential Rumiº), director/producer/tenor James Flannery (founder of the Yeats International Theatre Festival in Dublin), and some of North America's most beloved authors, award-winning children's book writers Jane Yolen and Gail E. -

33 JODEM, Vol. 11, No. 1, Issue 13, 2020 Idealization of Gandhian

JODEM, vol. 11, no. 1, issue 13, 2020 33 Idealization of Gandhian Myths in Bapu Sonnets: Devkota’s Romantic Perspective* Bam Dev Adhikari Associate Professor of English Tri-Chandra Multiple Campus, Kathmandu [email protected] Abstract Bapu sonnets were composed by great Nepali poet Laxmi Prasad Devkota just after the assassination of Mahatma Gandhi in India. Mahatma Gandhi used to be called „Bapu‟ by the commoners of India and these 38 sonnets written on him are supreme examples in terms of the form of the sonnet; but in terms of the content, the sonnets romanticize Gandhi and his contribution to India and Indian people. Written in the heydays of Mahatma Gandhi‟s popularity, the sonnets admire Mahatma Gandhi and deify him as a hero of Indian people. Mahatma Gandhi did play a great role in liberating India from British Raj but his role was controversial even in the Independence Movement of India and he became a more controversial figure in the subsequent years of his death. When these sonnets are read at the touchstone of how Gandhi is regarded today, they oversell Gandhi‟s contribution, for he was blamed as caste-biased, religion- biased, gender-biased and class-biased person. In this article, I am making an argument that the sonnets make overstatement about Gandhi and praise him excessively. Keywords: Admiration, commemoration, deification, controversy, romanticize Bapu Sonnets as Commemoration of Gandhi’s Life and Works Nepal‘s Great Poet Laxmi Prasad Devkota, known as Mahakavi (1909-1959) wrote 38 sonnets on Mahatma Gandhi and these sonnets got published entitled Bapu and Other Sonnets. -

Practical Campbell Joseph Campbell Foundation

Practical Campbell Movies: The Medium for Myth? In this Practical Campbell essay, Stephen Gerringer (bodhi_bliss) explores the mythic impact of modern mass media on our culture—and the way in which one of the most modern of art forms has helped to birth forth new myth. Joseph Campbell Foundation The Foundation was created in 1990 in order to preserve, protect and perpetuate the work of one of the twentieth century’s most original, influential thinkers. www.jcf.org • 800-330-Myth © 2006 by Joseph Campbell Foundation. This article is intended solely for the education and entertainment of the reader. Reproduction, alteration, transmission or commercial use of this article in any form without written permission of the Joseph Campbell Foundation is strictly prohibited. Please contact the Foundation before reproducing or quoting extensively from this article, in part or in whole. © 2006, Joseph Campbell Foundation • All rights reserved PRACTICAL CAMPBELL The Movies: Medium for Myth? [The modern myth] has to do with machines, airshots, the size of the universe, it’s got to deal with what we’re living with. Star Wars deals with the essential problem: Is the machine going to control humanity, or is the machine going to serve humanity? Darth Vader is a man taken over by a machine, he becomes a machine, and the state itself is a machine. There is no humanity in the state. What runs the world is economics and politics, and they have nothing to do with the spiritual life. So we are left with this void. It’s the job of the artist to create the new myths. -

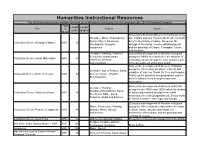

Humanities Instructional Resources

Humanities Instructional Resources The following resources are available for check out to Humanities Instructors from the Language Lab (TB 418 Redwood Campus) Type Length Length Title of Subject Notes (min) (pages) Media Surveys the Romantic Movement that began in the Literature; Music; Romanticism; late 17OO's and was characterized in the romantic Renoir, Monet, Rousseau, belief in the divinity of nature. Discusses the Civilization Series: Worship of Nature VHS 50 Wordsworth, Romantic writings of Rousseau, Goethe and Wordsworth composers and the paintings of Casper, Constable, Turner, and Friedrich. Literature; Painting; Industrial Surveys the development of Western civilization Revolution, humanitarian during the 1900's as evidenced in the advance of Civilization Series: Heroic Materialism VHS 53 reformers, Dickens, technology shown through the work of Brunel and Impressionists in the development of the atom bomb Surveys the development of Western civilization during the 18th century as shown in the art and Literature; Age of Reason; David, sculpture of Van Loo, David, De Troy and Houdon. Civilization Series: Smile of Reason VHS 49 DeTroy, Voltaire, Houdon, Points out the growth of humanitarianism and the Encyclopedists belief in advancement through reason and moderation. Surveys the development of Western civilization Literature; Painting; during the late 1700's and 1800's when the dreams Sculpture;Romanticism; Byron, Civilization Series: Fallacies of Hope VHS 50 of advancing mankind through reason and Beethoven, Blake, David, moderation -

One Face of the Hero: in Search of the Mythological Joseph Smith

One Face of the Hero: In Search of the Mythological Joseph Smith Edgar C. Snow, Jr. IN THE SPRING OF 19851 RECEIVED a telephone call from my local stake high councilor requesting that I give a talk to the Stake Aaronic Priesthood around a campfire at an annual stake camping trip. He wanted me to talk about Joseph Smith or the restoration of the priesthood. I accepted. At the time I was reading Richard Bushman's Joseph Smith and the Beginnings of Mormonism with great interest and a heightened sense of the adventure of the Smith family in bringing forth the Book of Mormon. I soon discovered that a campfire surrounded by twelve-to-eighteen- year-old boys was not the place for profound statements about the doc- trines of the priesthood or the achievements of Joseph Smith. Rather I realized that adventure stories from Joseph's life held the attention of these young men in the midst of hooting owls, a blazing fire, and thoughts of nighttime escapades. While standing in front of a crackling fire, I told many tales, includ- ing the discovery of the golden plates, the escape from Liberty Jail, and the shootout at the martyrdom of Joseph and Hyrum. To my amazement these stories became magical spells holding the gaze of all present. I felt somehow during this ritual of storytelling that we became one organism much the same way a congregation may feel spiritual oneness during a church conference while standing in unison singing "We Thank Thee, O God, for a Prophet." Instead of producing a "near-death experience" for the Stake Aaronic Priesthood, youth as well as their leaders, by talking theology, a "near-life experience" occurred when I told stories. -

Revisiting Joseph Campbell's the Power of Myth

Intermountain West Journal of Religious Studies Volume 5 Number 1 Spring 2014 Article 5 2014 Revisiting Joseph Campbell’s The Power of Myth Daniel Gorman Jr. University of Rochester Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/imwjournal Recommended Citation Gorman, Daniel Jr. "Revisiting Joseph Campbell’s The Power of Myth." Intermountain West Journal of Religious Studies 5, no. 1 (2014). https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/imwjournal/vol5/ iss1/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at DigitalCommons@USU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Intermountain West Journal of Religious Studies by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@USU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. IMW Journal of Religious Studies Vol. 5:1 73 DAN GORMAN, JR. is currently a senior and a Christopher Lasch Fellow in History at the University of Rochester. He will graduate in May 2014 with a B.A. in History and Religion. His major research interests are American politics, religion and culture, transnational history, critical theory in the post- postmodernist era, environmental conservation and sustainability, and the arts. In his spare time, he enjoys swing dancing, cello and voice performance, interfaith activism, and travel. 74 Dan Gorman, Jr.: Revisiting Joseph Campbell’s The Power of Myth ‡ Revisiting Joseph Campbell’s The Power of Myth ‡1 First published in 1988, The Power of Myth is the companion to Bill Moyers’ acclaimed television profile of Joseph Campbell.2 Power is comprised of eight transcribed conversations between Moyers, a theologian-turned-journalist,3 and Campbell, a comparative mythologist. -

Evaluating Joseph Campbell's Underexplored Ideas in the Light of Modern Psychology

Heroism Science Volume 4 Issue 1 Article 1 2019 Evaluating Joseph Campbell's Underexplored Ideas In the Light of Modern Psychology Leonard L. Martin University of Georgia, [email protected] James Conners University of Georgia, [email protected] Jacqueline A. Newbold University of Georgia, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.richmond.edu/heroism-science Part of the Social Psychology Commons, and the Transpersonal Psychology Commons Recommended Citation Martin, Leonard L.; Conners, James; and Newbold, Jacqueline A. (2019) "Evaluating Joseph Campbell's Underexplored Ideas In the Light of Modern Psychology," Heroism Science: Vol. 4 : Iss. 1 , Article 1. DOI: 10.26736/hs.2019.01.01 Available at: https://scholarship.richmond.edu/heroism-science/vol4/iss1/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by UR Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Heroism Science by an authorized editor of UR Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 1 Heroism Science: An Interdisciplinary Journal (ISSN 2573-7120) https://scholarship.richmond.edu/heroism-science/ Vol. 4 No. 1 (2019) Evaluating Joseph Campbell's Underexplored Ideas in the Light of Modern Psychology LEONARD L. MARTIN JAMES CONNERS JACQUELINE NEWBOLD1 University of Georgia [email protected] ABSTRACT: Joseph Campbell was a scholar of comparative mythology and religion who attained great popularity by promoting the importance of mythology in people's everyday lives. His ideas have not been subjected to rigorous testing, however. So, it is unclear if they are useful for people trying to attain optimal psychological functioning or if they could contribute to current research and theorizing in psychology.