Wireless Market Structures and Network Sharing”, OECD Digital Economy Papers, No

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

(Uk) Limited Pre Order Galaxy Buds Promotion Terms and Conditions

SAMSUNG ELECTRONICS (UK) LIMITED PRE ORDER GALAXY BUDS PROMOTION TERMS AND CONDITIONS Participants agree to be bound by these terms and conditions (the “Terms and Conditions”). Any information or instructions published by the Promoter about the Promotion at www.samsung.com/uk/offer/galaxys10-preorder and www.samsung.com/ie/offer/galaxys10-preorder form part of the Terms and Conditions. The Promoter 1. The Promoter is Samsung Electronics (UK) Limited, Samsung House, 1000 Hillswood Drive, Chertsey, Surrey, KT16 0PS (the “Promoter”). Promotion Period 2. The Promotion will commence at 00:01 (GMT) on 20 February 2019 and shall close at 23:59 (GMT) on the 7 March 2019 (the “Promotion Period”). Eligibility 3. To be eligible to participate in the Promotion you must be a resident (aged 18+) of or a company registered in the UK, Isle of Man, Channel Islands or Republic of Ireland (“Participant”). 4. Employees or agents of the Promoter that are involved in the operation of this Promotion or anyone professionally connected to this Promotion are not eligible to enter. 5. Network providers, retailers, distributors, resellers and any person who purchases a Promotion Product (defined below) for resale or otherwise not as the user of the Promotion Product, may not participate in this Promotion and is specifically excluded as a Participant. Offer 6. Participants who pre-order a new (i.e. not second hand) qualifying Samsung product as shown below in Table 1 (a “Promotion Product”) from a Participating Retailer shown in Table 1 below (“Participating Retailer”) in the UK, Channel Islands, Isle of Man or Republic of Ireland within the Promotion Period will be eligible to claim a pair of Samsung Galaxy Buds in white by redemption (the “Reward”). -

Providers'ervice Report Analyzes Competitive Rivalry in Non-Price Factors, Such As Coverage, Service Quality and Speed of Offerings

Federal Communications Commission DA 14-1862 competition policy authorities such as the U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ)." The approach taken in this Report is consistent with the policy of the DOJ. 7. This Report first provides an analysis of the overall competitive dynamics of the industry, describing the various types of entities and their positions vis a vis one another across indices such as market sharc and various financial indicators.'" The Report then presents a broad overview of trends and developments in the mobile marlretplacc that have taken place since the Sixteenth Report, such as subscribership growth, adoption and deployment of technologies, and usage trends. While most of the developments have been along a continuum of previously noted trends, the ongoing deployment and adoption nfl,TF, networks and the technologies they have enabled, has had a particularly profound effect throughout the mobile wireless marketplace during the period under review, 8. The Report then turns to an analysis of key inputs necessary for provision of mobile service, such as spectrum resources and network infrastructure. Spectrum, in pmticular, is the single most important input that wireless providers need for the provision of service and is a finite and scarce resource. The Repr&t t examines how the distribution of spectrum in the various bands affects competition. The Report next examines developments in the ways providers compete for and attract subscribers through pricing innovations, such as the decreased reliance on traditional handset. subsidies and term contracts. As part of this analysis, the analysis looks at the differences betwccn prc and postpaid market segments as well as ways in which those segments mc Finally„ the converging. -

Buying a Mobile Phone

Buying a mobile phone Getting started A SIM card is the small chip that goes into mobile phones allowing the phone to connect to the local network. Making calls in the UK using your own international SIM card is likely to be expensive so you might want to buy a new SIM or buy another mobile phone with a SIM included. It can sometimes be cheaper to buy an international calling card that will let you make calls home from a landline, mobile phone or phone box. You can buy calling cards from the newsagent’s shop opposite the Parkinson Building. Currently, when using a UK SIM, you will not be charged extra fees to use your UK allowance of minutes, texts or data plan when in countries within the European Economic Area (EEA). Some providers may also have offers for usage in other countries such as the US, so look out for this. There are two different ways to buy a mobile phone: pay-as-you-go or a contract. Please read the following information carefully to see what you will need to get started. Pay-as-you-go You can get a pay-as-you-go mobile phone or SIM card very quickly and it is easy to keep track of how much you are spending on calls. You can buy credit online, in supermarkets, newsagents, petrol stations and at some ATMs. You will also find a free pay-as-you-go SIM card for Lebara mobile in your Welcome Pack that includes £1 pre-loaded credit. You may be able to buy a SIM card in the UK and use it in your own phone from home. -

Décision N° 2020-1486 De L'arcep En Date Du 15 Décembre 2020

RÉPUBLIQUE FRANÇAISE Décision n° 2020-1486 de l’Autorité de régulation des communications électroniques, des postes et de la distribution de la presse en date du 15 décembre 2020 procédant à la levée de l’obligation de partage pour les nouveaux sites en zone de déploiement prioritaire de la société SFR L’Autorité de régulation des communications électroniques, des postes et de la distribution de la presse (ci-après « l’Arcep » ou « l’Autorité »), Vu le code des postes et des communications électroniques et notamment les articles L. 32-1, L. 33-1, L. 34-8, L. 36-7, L. 42, L. 42-1 et L. 42-2 ; Vu l’arrêté du 18 juillet 2001, modifié notamment par la décision n° 2018-0683 en date du 3 juillet 2018, autorisant la société française du radiotéléphone – SFR à établir et exploiter un réseau radioélectrique de troisième génération ouvert au public et à fournir le service téléphonique au public ; Vu la décision n° 2001-0647 de l’Arcep en date du 7 septembre 2001, modifiée notamment par la décision n° 2018-0683 en date du 3 juillet 2018, attribuant des fréquences à la société française du radiotéléphone - SFR pour l’établissement et l’exploitation d’un réseau mobile de troisième génération ; Vu la décision n° 2006-0140 de l’Arcep en date du 31 janvier 2006, modifiée notamment par la décision n° 2018-0683 en date du 3 juillet 2018, autorisant la société française du radiotéléphone - SFR à utiliser des fréquences dans les bandes 900 MHz et 1800 MHz pour établir et exploiter un réseau radioélectrique ouvert au public ; Vu la décision n° 2010-0633 de -

Страна Оператор Код В Счете MCC/MNC Австралия Vodafone

Страна Оператор Код в счете MCC/MNC Австралия Vodafone (на дисплее: Vodafone, VF) AUSVF 50503 SingTel Optus Pty Limited (на дисплее: Yes Optus) AUSOP 50502 Telstra (на дисплее: Telstra) AUSTA 50501 Австрия A1 Telekom Austria AG (на дисплее: А1) AUTPT 23201 T-Mobile Austria GmbH (на дисплее: T-Mobile A - A03, 232-03, max.mobil, A-max) AUTMM 23203 Hutchison Drei Austria GmbH (на дисплее: Orange A, Orange AT, One, A one, A 05, 232-05, 3 AT) AUTCA 23205 Аландские о-ва Alands Telekommunikation Ab (на дисплее: FI AMT, ALCOM) FINAM 24414 Азербайджан Azercell (на дисплее: Azercell) AZEAC 40001 Azerfon LLC (на дисплее: Nar, Azerfon, Aznar) AZEAF 40004 Bakcell LLC (на дисплее: AZE 02, Bakcell GSM2000, 400 02) AZEBC 40002 Албания Vodafone Albania (на дисплее: AL 02, VODAFONE, voda AL, 276-02) ALBVF 27602 ALBtelecom sh.a. (на дисплее: 276 03, Eagle) ALBEM 27603 Аргентина AMX Argentina S.A. - CLARO (на дисплее: CLARO Argentina, CTIARG, AR310, Claro AR) ARGCM 722310 Армения VEON Armenia CJSC (на дисплее: ARMO1; Beeline AM; RA-ARMGSM) ARM01 28301 UCOM LLC (на дисплее: UCOM, 28310, ARM10) ARMOR 28310 Бахрейн Bahrain Telecommunications Company (BATELCO) (на дисплее: BATELCO, 42601, BHRBT) BHRBT 42601 Zain Bahrain (на дисплее: BHR 02, MTC Vodafone, MTCVB, 426 02, zain BH) BHRMV 42602 Бельгия Orange Belgium SA/NV (на дисплее: Orange B) BELMO 20610 Telenet Group (на дисплее: BASE, BEL 20, 206-20) BELKO 20620 Proximus (на дисплее: B PROXIMUS, BEL PROXIMUS) BELTB 20601 Болгария A1 Bulgaria (Mobiltel EAD) (на дисплее: A1 BG, 284 01, Mtel) BGR01 28401 TELENOR BULGARIA EAD (на дисплее: Telenor BG) BGRCM 28405 Боливия NuevaTel S.A. -

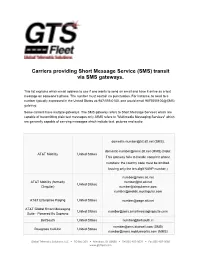

SMS) Transit Via SMS Gateways

Carriers providing Short Message Service (SMS) transit via SMS gateways. This list explains which email address to use if one wants to send an email and have it arrive as a text message on someone's phone. The number must contain no punctuation. For instance, to send to a number typically expressed in the United States as 987-555-0100, one would email 9875550100@SMS- gateway. Some carriers have multiple gateways. The SMS gateway refers to Short Message Services which are capable of transmitting plain text messages only. MMS refers to "Multimedia Messaging Services" which are generally capable of carrying messages which include text, pictures and audio [email protected] (SMS), [email protected] (MMS) (Note: AT&T Mobility United States This gateway fails to handle complete phone numbers; the country code must be omitted, leaving only the ten-digit NANP number.) [email protected] AT&T Mobility (formerly [email protected] United States Cingular) [email protected] [email protected] AT&T Enterprise Paging United States [email protected] AT&T Global Smart Messaging United States [email protected] Suite - Powered By Soprano BellSouth United States [email protected] [email protected] (SMS) Bluegrass Cellular United States [email protected] (MMS) Global Telematic Solutions, LLC • PO Box 269 • Meridian, ID 83680 • Tel 855-487-9679 • Fax 855-487-9680 www.gtsfleet.com [email protected] (SMS) Boost Mobile United States [email protected] (MMS) Cellcom United States -

Goodwill Impairment Test of the Cellular Segment June 30Th, 2019

Bezeq The Israel Telecommunication Corporation Limited Goodwill Impairment Test of the Cellular Segment June 30th, 2019 August 2019 14 Kreminitzky St., Tel Aviv 6789912 I Tel.: 03-5617801 I Fax: 077-3181607 Introduction and Limit of Liability • We were retained by Bezeq The Israel Telecommunication Corp. Ltd. (hereunder “Bezeq” and/or “Bezeq Group” and/or the ”Client”) to prepare a goodwill impairment test report (the “Report”) of the cellular business unit (hereunder: “Pelephone” and/or the “Cellular Segment”) as of June 30th, 2019. • The Report intended solely for the use of the Client and is . This Report may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, and the findings of this Report may not be used by a third party for any purpose, without our expressed written consent. Notwithstanding any of the above, this Report may be included in the Client’s financial statements of as of June. 30, 2017. • For the purpose of preparing this Report, we relied upon financial and other information including prospective financial information obtained from the Company and/or the Client and/or anyone on their behalf (the “Information”). We assumed that the Information is credible and therefore did not perform an independent audit of the information. In addition, nothing suggesting that the Information may be unreasonable has come to our attention. The Information has not been examined in an independent manner, and therefore this Report does not constitute a verification of the Information’s correctness, completeness and accuracy. If the case that the Information is not complete nor accurate or credible, the results of this valuation might change. -

Broadband and Mobile

Benenden Parish Plan Communication: Broadband and Mobile Issue 1.1 03/05/2014 Benenden Broadband and Mobile Key Points Broadband Introduction of Superfast Broadband should be complete by March 2015. 96% of postcodes within the TN17 4xx Benenden exchange area will attain Superfast Broadband speeds (25 Mbps and above) Only BT and Talk Talk have their own broadband equipment in Benenden Exchange providing maximum speeds of up to 24 Mbps. Other ISPs use a BT Wholesale connection enabling service at either 24 Mbps or just 8 Mbps (e.g. Sky) WiFi Broadband may be available for some households in Benenden from CallFlow and VFast 4G Mobile services will enable broadband comparable speeds beginning in Benenden during 2014 Poor broadband performance may be due to electrical interference and internal (or external) wiring problems. Mobile O2 have plans to improve 2G and 3G coverage and also introduce 4G services in 2014. Home coverage can also be improved by using a signal booster (femtocell) PAYG SIM cards can be a useful tool to determine the best provider in addition to online network coverage maps. If you decide to change provider your current mobile company will inevitably offer you inducements to stay (e.g. lower charges, improved terms, free femtocell). This also applies to Broadband. Broadband DSL Broadband (Digital Subscriber Line) The most significant (but not the only) factor limiting Broadband speed is the physical distance between the household and the equipment in the telephone exchange. Rural telephone exchange areas tend to be larger than those in urban areas and therefore people are more likely to live further from the exchange and consequently suffer from poor broadband performance. -

WELCOME to the WORLD of ETSI an Overview of the European Telecommunication Standards Institute

WELCOME TO THE WORLD OF ETSI An overview of the European Telecommunication Standards Institute © ETSI 2016. All rights reserved © ETSI 2016. All rights reserved European roots, global outreach ETSI is a world-leading standards developing organization for Information and Communication Technologies (ICT) Founded initially to serve European needs, ETSI has become highly- respected as a producer of technical standards for worldwide use © ETSI 2016. All rights reserved Products & services Technical specifications and standards with global application Support to industry and European regulation Specification & testing methodologies Interoperability testing © ETSI 2016. All rights reserved Membership Over 800 companies, big and small, from 66 countries on 5 continents Manufacturers, network operators, service and content providers, national administrations, ministries, universities, research bodies, consultancies, user organizations A powerful and dynamic mix of skills, resources and ambitions © ETSI 2016. All rights reserved Independence Independent of all other organizations and structures Respected for neutrality and trustworthiness Esteemed for our world-leading Intellectual Property Rights (IPR) Policy © ETSI 2016. All rights reserved Collaboration Strategic collaboration with numerous global and regional standards-making organizations and industry groupings Formally recognized as a European Standards Organization, with a global perspective Contributing technical standards to support regulation Defining radio frequency requirements for -

The Carphone Warehouse Limited (“CPW” Or the “Firm”)

FINAL NOTICE To: The Carphone Warehouse Limited (“CPW” or the “Firm”) Reference Number: 312912 Address: 1 Portal Way, London W3 6RS Date: 13 March 2019 1. ACTION 1.1 For the reasons given in this Final Notice, the Authority hereby imposes on CPW a financial penalty of £29,107,600 pursuant to section 206 of the Act. 1.2 The Firm agreed to settle all issues of fact and liability and therefore qualified for a 30% discount under the Authority’s executive settlement procedures. Were it not for this discount, the Authority would have imposed a financial penalty of £41,582,300 on the Firm. 2. SUMMARY OF REASONS 2.1. On the basis of the facts and matters described below the Authority considers that between 1 December 2008 and 30 June 2015 (“the relevant period”), CPW breached Principle 3 (Management and control), Principle 6 (Customers’ interests) and Principle 9 (Customers: relationships of trust) of the Authority’s Principles for Businesses (“the Principles”). 2.2 During the relevant period, CPW failed to equip its sales consultants to give suitable advice to customers in respect of “Geek Squad”, its mobile phone insurance and technical support product. 2.3 CPW offered versions of Geek Squad in respect of products other than mobile phones, but all of its activities in respect of such versions of Geek Squad fall outside the scope of this Notice. CPW did not undertake regulated activities in its sales of the version of Geek Squad for “pay as you go” customers between October 2010 and October 2013, and accordingly those sales also fall outside the scope of this Notice. -

Cellcom Israel Ltd. Announces Agreement to Purchase Golan Telecom

November 5, 2015 Cellcom Israel Ltd. Announces Agreement To Purchase Golan Telecom NETANYA, Israel, Nov. 5, 2015 /PRNewswire/ -- Cellcom Israel Ltd. (NYSE: CEL) (TASE: CEL) (hereinafter: the "Company") announced today that the Company entered an agreement (the "Agreement" with Golan Telecom Ltd., or Golan, and its shareholders for the purchase of 100% of the shares of Golan, an Israeli cellular operator, for the sum of NIS 1.17 billion ("Purchase Price"). Golan is one of the four other Mobile Network Operators ("MNO") operating in Israel in addition to Cellcom Israel. It launched operations in 2012 with a strong brand recognized for low-cost services, and primarily provides cellular services to approximately 900,000 customers (as of November 2015), with a comparatively low churn. Golan is expected to end 2015 with total revenues exceeding NIS 500 million1. The Purchase Price represents an Enterprise Value, or EV2 of NIS 1 billion for Golan and EV/Adjusted EBITDA multiple of approximately 5.0, based on Golan's forecasted Adjusted EBITDA for 2015 (NIS 204 million)3. Ami Erel, the Company's Chairman of the Board, said: "In the last few years, Cellcom Group has repeatedly proven its ability to increase its service offerings, going from a cellular only operator to a full service communications group, with cellular, fixed line, internet and TV offerings, and succeeding despite the fierce competition. The acquisition of Golan Telecom will allow us to add a low-cost brand to our portfolio, and I'm confident that Cellcom's management will be able to successfully combine Golan's operations as the Company's low cost brand. -

5G Implementation in Non-EU Countries of Europe Region

5G IMPLEMENTATION IN NON-EU COUNTRIES OF THE EUROPE REGION ITU Regional Initiative for Europe on Broadband Infrastructure, Broadcasting and Spectrum Management © ITU November 2020 Version 1.2 5G Implementation in non-EU countries of the Europe Region ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This paper was developed by the ITU Office for Europe within the framework of the ITU Regional Initiative for Europe on broadband infrastructure, broadcasting and spectrum management. It was elaborated by ITU Office for Europe team including Mr. Iago Bojczuk, Junior Policy Analyst, and Mr. Julian McNeill, Consultant, under the supervision and direction of Mr. Jaroslaw Ponder, Head of ITU Office for Europe. Moreover, important feedback has been provided to this report by: - Electronic and Postal Communications Authority (AKEP), Albania; - Ministry of Infrastructure and Energy, Albania; - Communications Regulatory Agency (CRA), Bosnia and Herzegovina; - Post and Telecom Administration (PTA), Iceland; - Ministry of Communications of Israel; - Office for Communications of Liechtenstein; - Ministry of Economy and Infrastructure of Moldova; - National Regulatory Agency for Electronic Communications and Information Technology (ANRCETI); - Ministry of Economy, Montenegro; - Agency for Electronic Communications and Postal Services (EKIP), Montenegro; - Ministry of Information Society and Administration, North Macedonia; - Agency for Electronic Communications of North Macedonia; - Ministry of Trade, Tourism and Telecommunications, Serbia; - Information and Communication Technologies Authority, Turkey; - National Commission for the State Regulation of Communications and Informatization, Ukraine; - Department for Digital, Culture, Media & Sport (DCMS), United Kingdom; - Dicastero per la Comunicazione - Direzione Tecnologica, Vatican City. The paper was prepared as the background contribution to the ITU Regional Forum for Europe on 5G strategies, policies and implementation, held on 22 and 23 October 2020.