High Dynamic Range Imaging

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Logarithmic Image Sensor for Wide Dynamic Range Stereo Vision System

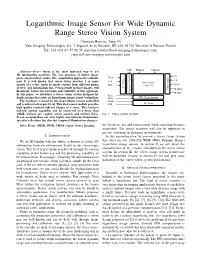

Logarithmic Image Sensor For Wide Dynamic Range Stereo Vision System Christian Bouvier, Yang Ni New Imaging Technologies SA, 1 Impasse de la Noisette, BP 426, 91370 Verrieres le Buisson France Tel: +33 (0)1 64 47 88 58 [email protected], [email protected] NEG PIXbias COLbias Abstract—Stereo vision is the most universal way to get 3D information passively. The fast progress of digital image G1 processing hardware makes this computation approach realizable Vsync G2 Vck now. It is well known that stereo vision matches 2 or more Control Amp Pixel Array - Scan Offset images of a scene, taken by image sensors from different points RST - 1280x720 of view. Any information loss, even partially in those images, will V Video Out1 drastically reduce the precision and reliability of this approach. Exposure Out2 In this paper, we introduce a stereo vision system designed for RD1 depth sensing that relies on logarithmic image sensor technology. RD2 FPN Compensation The hardware is based on dual logarithmic sensors controlled Hsync and synchronized at pixel level. This dual sensor module provides Hck H - Scan high quality contrast indexed images of a scene. This contrast indexed sensing capability can be conserved over more than 140dB without any explicit sensor control and without delay. Fig. 1. Sensor general structure. It can accommodate not only highly non-uniform illumination, specular reflections but also fast temporal illumination changes. Index Terms—HDR, WDR, CMOS sensor, Stereo Imaging. the details are lost and consequently depth extraction becomes impossible. The sensor reactivity will also be important to prevent saturation in changing environments. -

Receiver Dynamic Range: Part 2

The Communications Edge™ Tech-note Author: Robert E. Watson Receiver Dynamic Range: Part 2 Part 1 of this article reviews receiver mea- the receiver can process acceptably. In sim- NF is the receiver noise figure in dB surements which, taken as a group, describe plest terms, it is the difference in dB This dynamic range definition has the receiver dynamic range. Part 2 introduces between the inband 1-dB compression point advantage of being relatively easy to measure comprehensive measurements that attempt and the minimum-receivable signal level. without ambiguity but, unfortunately, it to characterize a receiver’s dynamic range as The compression point is obvious enough; assumes that the receiver has only a single a single number. however, the minimum-receivable signal signal at its input and that the signal is must be identified. desired. For deep-space receivers, this may be COMPREHENSIVE MEASURE- a reasonable assumption, but the terrestrial MENTS There are a number of candidates for mini- mum-receivable signal level, including: sphere is not usually so benign. For specifi- The following receiver measurements and “minimum-discernable signal” (MDS), tan- cation of general-purpose receivers, some specifications attempt to define overall gential sensitivity, 10-dB SNR, and receiver interfering signals must be assumed, and this receiver dynamic range as a single number noise floor. Both MDS and tangential sensi- is what the other definitions of receiver which can be used both to predict overall tivity are based on subjective judgments of dynamic range do. receiver performance and as a figure of merit signal strength, which differ significantly to compare competing receivers. -

Ultra HD Playout & Delivery

Ultra HD Playout & Delivery SOLUTION BRIEF The next major advancement in television has arrived: Ultra HD. By 2020 more than 40 million consumers around the world are projected to be watching close to 250 linear UHD channels, a figure that doesn’t include VOD (video-on-demand) or OTT (over-the-top) UHD services. A complete UHD playout and delivery solution from Harmonic will help you to meet that demand. 4K UHD delivers a screen resolution four times that of 1080p60. Not to be confused with the 4K digital cinema format, a professional production and cinema standard with a resolution of 4096 x 2160, UHD is a broadcast and OTT standard with a video resolution of 3840 x 2160 pixels at 24/30 fps and 8-bit color sampling. Second-generation UHD specifications will reach a frame rate of 50/60 fps at 10 bits. When combined with advanced technologies such as high dynamic range (HDR) and wide color gamut (WCG), the home viewing experience will be unlike anything previously available. The expected demand for UHD content will include all types of programming, from VOD movie channels to live global sporting events such as the World Cup and Olympics. UHD-native channel deployments are already on the rise, including the first linear UHD channel in North America, NASA TV UHD, launched in 2015 via a partnership between Harmonic and NASA’s Marshall Space Flight Center. The channel highlights incredible imagery from the U.S. space program using an end-to-end UHD playout, encoding and delivery solution from Harmonic. The Harmonic UHD solution incorporates the latest developments in IP networking and compression technology, including HEVC (High- Efficiency Video Coding) signal transport and HDR enhancement. -

For the Falcon™ Range of Microphone Products (Ba5105)

Technical Documentation Microphone Handbook For the Falcon™ Range of Microphone Products Brüel&Kjær B K WORLD HEADQUARTERS: DK-2850 Nærum • Denmark • Telephone: +4542800500 •Telex: 37316 bruka dk • Fax: +4542801405 • e-mail: [email protected] • Internet: http://www.bk.dk BA 5105 –12 Microphone Handbook Revision February 1995 Brüel & Kjær Falcon™ Range of Microphone Products BA 5105 –12 Microphone Handbook Trademarks Microsoft is a registered trademark and Windows is a trademark of Microsoft Cor- poration. Copyright © 1994, 1995, Brüel & Kjær A/S All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or distributed in any form or by any means without prior consent in writing from Brüel & Kjær A/S, Nærum, Denmark. 0 − 2 Falcon™ Range of Microphone Products Brüel & Kjær Microphone Handbook Contents 1. Introduction....................................................................................................................... 1 – 1 1.1 About the Microphone Handbook............................................................................... 1 – 2 1.2 About the Falcon™ Range of Microphone Products.................................................. 1 – 2 1.3 The Microphones ......................................................................................................... 1 – 2 1.4 The Preamplifiers........................................................................................................ 1 – 8 1 2. Prepolarized Free-field /2" Microphone Type 4188....................... 2 – 1 2.1 Introduction ................................................................................................................ -

Frequency Response and Bode Plots

1 Frequency Response and Bode Plots 1.1 Preliminaries The steady-state sinusoidal frequency-response of a circuit is described by the phasor transfer function Hj( ) . A Bode plot is a graph of the magnitude (in dB) or phase of the transfer function versus frequency. Of course we can easily program the transfer function into a computer to make such plots, and for very complicated transfer functions this may be our only recourse. But in many cases the key features of the plot can be quickly sketched by hand using some simple rules that identify the impact of the poles and zeroes in shaping the frequency response. The advantage of this approach is the insight it provides on how the circuit elements influence the frequency response. This is especially important in the design of frequency-selective circuits. We will first consider how to generate Bode plots for simple poles, and then discuss how to handle the general second-order response. Before doing this, however, it may be helpful to review some properties of transfer functions, the decibel scale, and properties of the log function. Poles, Zeroes, and Stability The s-domain transfer function is always a rational polynomial function of the form Ns() smm as12 a s m asa Hs() K K mm12 10 (1.1) nn12 n Ds() s bsnn12 b s bsb 10 As we have seen already, the polynomials in the numerator and denominator are factored to find the poles and zeroes; these are the values of s that make the numerator or denominator zero. If we write the zeroes as zz123,, zetc., and similarly write the poles as pp123,, p , then Hs( ) can be written in factored form as ()()()s zsz sz Hs() K 12 m (1.2) ()()()s psp12 sp n 1 © Bob York 2009 2 Frequency Response and Bode Plots The pole and zero locations can be real or complex. -

Signal-To-Noise Ratio and Dynamic Range Definitions

Signal-to-noise ratio and dynamic range definitions The Signal-to-Noise Ratio (SNR) and Dynamic Range (DR) are two common parameters used to specify the electrical performance of a spectrometer. This technical note will describe how they are defined and how to measure and calculate them. Figure 1: Definitions of SNR and SR. The signal out of the spectrometer is a digital signal between 0 and 2N-1, where N is the number of bits in the Analogue-to-Digital (A/D) converter on the electronics. Typical numbers for N range from 10 to 16 leading to maximum signal level between 1,023 and 65,535 counts. The Noise is the stochastic variation of the signal around a mean value. In Figure 1 we have shown a spectrum with a single peak in wavelength and time. As indicated on the figure the peak signal level will fluctuate a small amount around the mean value due to the noise of the electronics. Noise is measured by the Root-Mean-Squared (RMS) value of the fluctuations over time. The SNR is defined as the average over time of the peak signal divided by the RMS noise of the peak signal over the same time. In order to get an accurate result for the SNR it is generally required to measure over 25 -50 time samples of the spectrum. It is very important that your input to the spectrometer is constant during SNR measurements. Otherwise, you will be measuring other things like drift of you lamp power or time dependent signal levels from your sample. -

High Dynamic Range Ultrasound Imaging

The final publication is available at http://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s11548-018-1729-3 Int J CARS manuscript No. (will be inserted by the editor) High Dynamic Range Ultrasound Imaging Alperen Degirmenci · Douglas P. Perrin · Robert D. Howe Received: 26 January 2018 Abstract Purpose High dynamic range (HDR) imaging is a popular computational photography technique that has found its way into every modern smartphone and camera. In HDR imaging, images acquired at different exposures are combined to increase the luminance range of the final image, thereby extending the limited dynamic range of the camera. Ultrasound imaging suffers from limited dynamic range as well; at higher power levels, the hyperechogenic tissue is overexposed, whereas at lower power levels, hypoechogenic tissue details are not visible. In this work, we apply HDR techniques to ultrasound imaging, where we combine ultrasound images acquired at different power levels to improve the level of detail visible in the final image. Methods Ultrasound images of ex vivo and in vivo tissue are acquired at different acoustic power levels and then combined to generate HDR ultrasound (HDR-US) images. The performance of five tone mapping operators is quantitatively evaluated using a similarity metric to determine the most suitable mapping for HDR-US imaging. Results The ex vivo and in vivo results demonstrated that HDR-US imaging enables visualizing both hyper- and hypoechogenic tissue at once in a single image. The Durand tone mapping operator preserved the most amount of detail across the dynamic range. Conclusions Our results strongly suggest that HDR-US imaging can improve the utility of ultrasound in image-based diagnosis and procedure guidance. -

JPEG-HDR: a Backwards-Compatible, High Dynamic Range Extension to JPEG

JPEG-HDR: A Backwards-Compatible, High Dynamic Range Extension to JPEG Greg Ward Maryann Simmons BrightSide Technologies Walt Disney Feature Animation Abstract What we really need for HDR digital imaging is a compact The transition from traditional 24-bit RGB to high dynamic range representation that looks and displays like an output-referred (HDR) images is hindered by excessively large file formats with JPEG, but holds the extra information needed to enable it as a no backwards compatibility. In this paper, we demonstrate a scene-referred standard. The next generation of HDR cameras simple approach to HDR encoding that parallels the evolution of will then be able to write to this format without fear that the color television from its grayscale beginnings. A tone-mapped software on the receiving end won’t know what to do with it. version of each HDR original is accompanied by restorative Conventional image manipulation and display software will see information carried in a subband of a standard output-referred only the tone-mapped version of the image, gaining some benefit image. This subband contains a compressed ratio image, which from the HDR capture due to its better exposure. HDR-enabled when multiplied by the tone-mapped foreground, recovers the software will have full access to the original dynamic range HDR original. The tone-mapped image data is also compressed, recorded by the camera, permitting large exposure shifts and and the composite is delivered in a standard JPEG wrapper. To contrast manipulation during image editing in an extended color naïve software, the image looks like any other, and displays as a gamut. -

Computational Entropy and Information Leakage∗

Computational Entropy and Information Leakage∗ Benjamin Fuller Leonid Reyzin Boston University fbfuller,[email protected] February 10, 2011 Abstract We investigate how information leakage reduces computational entropy of a random variable X. Recall that HILL and metric computational entropy are parameterized by quality (how distinguishable is X from a variable Z that has true entropy) and quantity (how much true entropy is there in Z). We prove an intuitively natural result: conditioning on an event of probability p reduces the quality of metric entropy by a factor of p and the quantity of metric entropy by log2 1=p (note that this means that the reduction in quantity and quality is the same, because the quantity of entropy is measured on logarithmic scale). Our result improves previous bounds of Dziembowski and Pietrzak (FOCS 2008), where the loss in the quantity of entropy was related to its original quality. The use of metric entropy simplifies the analogous the result of Reingold et. al. (FOCS 2008) for HILL entropy. Further, we simplify dealing with information leakage by investigating conditional metric entropy. We show that, conditioned on leakage of λ bits, metric entropy gets reduced by a factor 2λ in quality and λ in quantity. ∗Most of the results of this paper have been incorporated into [FOR12a] (conference version in [FOR12b]), where they are applied to the problem of building deterministic encryption. This paper contains a more focused exposition of the results on computational entropy, including some results that do not appear in [FOR12a]: namely, Theorem 3.6, Theorem 3.10, proof of Theorem 3.2, and results in Appendix A. -

Preview Only

AES-6id-2006 (r2011) AES information document for digital audio - Personal computer audio quality measurements Published by Audio Engineering Society, Inc. Copyright © 2006 by the Audio Engineering Society Preview only Abstract This document focuses on the measurement of audio quality specifications in a PC environment. Each specification listed has a definition and an example measurement technique. Also included is a detailed description of example test setups to measure each specification. An AES standard implies a consensus of those directly and materially affected by its scope and provisions and is intended as a guide to aid the manufacturer, the consumer, and the general public. An AES information document is a form of standard containing a summary of scientific and technical information; originated by a technically competent writing group; important to the preparation and justification of an AES standard or to the understanding and application of such information to a specific technical subject. An AES information document implies the same consensus as an AES standard. However, dissenting comments may be published with the document. The existence of an AES standard or AES information document does not in any respect preclude anyone, whether or not he or she has approved the document, from manufacturing, marketing, purchasing, or using products, processes, or procedures not conforming to the standard. Attention is drawn to the possibility that some of the elements of this AES standard or information document may be the subject of patent rights. AES shall not be held responsible for identifying any or all such patents. This document is subject to periodicwww.aes.org/standards review and users are cautioned to obtain the latest edition and printing. -

A Weakly Informative Default Prior Distribution for Logistic and Other

The Annals of Applied Statistics 2008, Vol. 2, No. 4, 1360–1383 DOI: 10.1214/08-AOAS191 c Institute of Mathematical Statistics, 2008 A WEAKLY INFORMATIVE DEFAULT PRIOR DISTRIBUTION FOR LOGISTIC AND OTHER REGRESSION MODELS By Andrew Gelman, Aleks Jakulin, Maria Grazia Pittau and Yu-Sung Su Columbia University, Columbia University, University of Rome, and City University of New York We propose a new prior distribution for classical (nonhierarchi- cal) logistic regression models, constructed by first scaling all nonbi- nary variables to have mean 0 and standard deviation 0.5, and then placing independent Student-t prior distributions on the coefficients. As a default choice, we recommend the Cauchy distribution with cen- ter 0 and scale 2.5, which in the simplest setting is a longer-tailed version of the distribution attained by assuming one-half additional success and one-half additional failure in a logistic regression. Cross- validation on a corpus of datasets shows the Cauchy class of prior dis- tributions to outperform existing implementations of Gaussian and Laplace priors. We recommend this prior distribution as a default choice for rou- tine applied use. It has the advantage of always giving answers, even when there is complete separation in logistic regression (a common problem, even when the sample size is large and the number of pre- dictors is small), and also automatically applying more shrinkage to higher-order interactions. This can be useful in routine data analy- sis as well as in automated procedures such as chained equations for missing-data imputation. We implement a procedure to fit generalized linear models in R with the Student-t prior distribution by incorporating an approxi- mate EM algorithm into the usual iteratively weighted least squares. -

1 1. Data Transformations

260 Archives ofDisease in Childhood 1993; 69: 260-264 STATISTICS FROM THE INSIDE Arch Dis Child: first published as 10.1136/adc.69.2.260 on 1 August 1993. Downloaded from 1 1. Data transformations M J R Healy Additive and multiplicative effects adding a constant quantity to the correspond- In the statistical analyses for comparing two ing before readings. Exactly the same is true of groups of continuous observations which I the unpaired situation, as when we compare have so far considered, certain assumptions independent samples of treated and control have been made about the data being analysed. patients. Here the assumption is that we can One of these is Normality of distribution; in derive the distribution ofpatient readings from both the paired and the unpaired situation, the that of control readings by shifting the latter mathematical theory underlying the signifi- bodily along the axis, and this again amounts cance probabilities attached to different values to adding a constant amount to each of the of t is based on the assumption that the obser- control variate values (fig 1). vations are drawn from Normal distributions. This is not the only way in which two groups In the unpaired situation, we make the further of readings can be related in practice. Suppose assumption that the distributions in the two I asked you to guess the size of the effect of groups which are being compared have equal some treatment for (say) increasing forced standard deviations - this assumption allows us expiratory volume in one second in asthmatic to simplify the analysis and to gain a certain children.