Ch'ing Dynasty Silver Tael Notes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chinese Underground Banking and 'Daigou'

Chinese Underground Banking and ‘Daigou’ October 2019 NAC/NECC v1.0 Purpose This document has been compiled by the National Crime Agency’s National Assessment Centre from the latest information available to the NCA regarding the abuse of Chinese Underground Banking and ‘Daigou’ for money laundering purposes. It has been produced to provide supporting information for the application by financial investigators from any force or agency for Account Freezing Orders and other orders and warrants under the Proceeds of Crime Act 2002. It can also be used for any other related purpose. This document is not protectively marked. Executive Summary • The transfer of funds for personal purposes out of China by Chinese citizens is tightly regulated by the Chinese government, and in all but exceptional circumstances is limited to the equivalent of USD 50,000 per year. All such transactions, without exception, are required to be carried out through a foreign exchange account opened with a Chinese bank for the purpose. The regulations nevertheless provide an accessible, legitimate and auditable mechanism for Chinese citizens to transfer funds overseas. • Chinese citizens who, for their own reasons, choose not to use the legitimate route stipulated by the Chinese government for such transactions, frequently use a form of Informal Value Transfer System (IVTS) known as ‘Underground Banking’ to carry them out instead. Evidence suggests that this practice is widespread amongst the Chinese diaspora in the UK. • Evidence from successful money laundering prosecutions in the UK has shown that Chinese Underground Banking is abused for the purposes of laundering money derived from criminal offences, by utilising cash generated from crime in the UK to settle separate and unconnected inward Underground Banking remittances to Chinese citizens in the UK. -

The History of the Yen Bloc Before the Second World War

@.PPO8PPTJL ࢎҮ 1.ಕ BOZQSJOUJOH QNBD ȇ ȇ Destined to Fail? The History of the Yen Bloc before the Second World War Woosik Moon The formation of yen bloc did not result in the economic and monetary integration of East Asian economies. Rather it led to the increasing disintegration of East Asian economies. Compared to Japan, Asian regions and countries had to suffer from higher inflation. In fact, the farther the countries were away from Japan, the more their central banks had to print the money and the higher their inflations were. Moreover, the income gap between Japan and other Asian countries widened. It means that the regionalization centered on Japanese yen was destined to fail, suggesting that the Co-prosperity Area was nothing but a strategy of regional dominance, not of regional cooperation. The impact was quite long lasting because it still haunts East Asian countries, contributing to the nourishment of their distrust vis-à-vis Japan, and throws a shadow on the recent monetary and financial cooperation movements in East Asia. This experience highlights the importance of responsible actions on the part of leading countries to boost regional solidarity and cohesion for the viability and sustainability of regional monetary system. 1. Introduction There is now a growing literature that argues for closer monetary and financial cooperation in East Asia, reflecting rising economic and political interdependence between countries in the region. If such a cooperation happens, leading countries should assume corresponding responsibilities. For, the viability of the system depends on their responsible actions to boost regional solidarity and cohesion. -

Lu Zhiqiang China Oceanwide

08 Investment.FIN.qxp_Layout 1 14/9/16 12:21 pm Page 81 Week in China China’s Tycoons Investment Lu Zhiqiang China Oceanwide Oceanwide Holdings, its Shenzhen-listed property unit, had a total asset value of Rmb118 billion in 2015. Hurun’s China Rich List He is the key ranked Lu as China’s 8th richest man in 2015 investor behind with a net worth of Rmb83 billlion. Minsheng Bank and Legend Guanxi Holdings A long-term ally of Liu Chuanzhi, who is known as the ‘godfather of Chinese entrepreneurs’, Oceanwide acquired a 29% stake in Legend Holdings (the parent firm of Lenovo) in 2009 from the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences for Rmb2.7 billion. The transaction was symbolic as it marked the dismantling of Legend’s SOE status. Lu and Liu also collaborated to establish the exclusive Taishan Club in 1993, an unofficial association of entrepreneurs named after the most famous mountain in Shandong. Born in Shandong province in 1951, Lu In fact, according to NetEase Finance, it was graduated from the elite Shanghai university during the Taishan Club’s inaugural meeting – Fudan. His first job was as a technician with hosted by Lu in Shandong – that the idea of the Shandong Weifang Diesel Engine Factory. setting up a non-SOE bank was hatched and the proposal was thereafter sent to Zhu Getting started Rongji. The result was the establishment of Lu left the state sector to become an China Minsheng Bank in 1996. entrepreneur and set up China Oceanwide. Initially it focused on education and training, Minsheng takeover? but when the government initiated housing Oceanwide was one of the 59 private sector reform in 1988, Lu moved into real estate. -

The Digital Yuan and China's Potential Financial Revolution

JULY 2020 The digital Yuan and China’s potential financial revolution: A primer on Central Bank Digital Currencies (CBDCs) BY STEWART PATERSON RESEARCH FELLOW, HINRICH FOUNDATION Contents FOREWORD 3 INTRODUCTION 4 WHAT IS IT AND WHAT COULD IT BECOME? 5 THE EFFICACY AND SCOPE OF STABILIZATION POLICY 7 CHINA’S FISCAL SYSTEM AND TAXATION 9 CHINA AND CREDIT AND THE BANKING SYSTEM 11 SEIGNIORAGE 12 INTERNATIONAL AND TRADE RAMIFICATIONS 13 CONCLUSIONS 16 RESEARCHER BIO: STEWART PATERSON 17 THE DIGITAL YUAN AND CHINA’S POTENTIAL FINANCIAL REVOLUTION Copyright © Hinrich Foundation. All Rights Reserved. 2 Foreword China is leading the way among major economies in trialing a Central Bank Digital Currency (CBDC). Given China’s technological ability and the speed of adoption of new payment methods by Chinese consumers, we should not be surprised if the CBDC takes off in a major way, displacing physical cash in the economy over the next few years. The power that this gives to the state is enormous, both in terms of law enforcement, and potentially, in improving economic management through avenues such as surveillance of the shadow banking system, fiscal tax raising power, and more efficient pass through of monetary policy. A CBDC has the potential to transform the efficacy of state involvement in economic management and widens the scope of potential state economic action. This paper explains how a CBDC could operate domestically; specifically, the impact it could have on the Chinese economy and society. It also looks at the possible international implications for trade and geopolitics. THE DIGITAL YUAN AND CHINA’S POTENTIAL FINANCIAL REVOLUTION Copyright © Hinrich Foundation. -

A Chinese Opinion on Leprosy, Being a Tpanslation of A

A CHINESE OPINION ON LEPROSY, BEINGA TPANSLATIONOF A CHAPTERFROM THE MEDICALSTANDARD-WORK Imperial edition of the Golden Mirror for the medical class1) BY B. A. J. VAN WETTUM. ' LEPROSY. Leprosy always takes its origin from pestilential miasms. Its causes are three in number, and five injurious forms are distinguished. Also five forms with mortification of some part, which make it a most loathsome disease. By self-restraint in the first stage of his illness, the patient may perhaps preserve his COMMENTARY. The ancient name of this disease was - (pestilential "wind") This", JI, means "wind with poison in it". 1) First chapter of the 87tb volume. It was published in the 7th year of the reign of K'ien-Lung,A.D. 1742. According to Wylie, it is one of the best works of moderntimes for general medicalinformation. (A Wylie, Notes on Chineseliterature, pag. 82). It bas a 2) The. above forms the text of the essay. the shape of $ (rhyme) and consistsof four lines each of seven words. In the arrangementof these, not much care is taken with to and regard 2fi: fà (rhytm) flfi (rhyme). 3) The true meaningof the character as occurringin the present essay,is not 257 The Canon 4) says: "this If. means that the blood and the vital ' ' fluid are hot and spoiled". The vital fluid is no longer pure. That is the reason why the nosebone gets injured, the color of the face destroyed and the skin is covered with boils and sores. A poisonous wind has stationed itself in the veins and does not go away. -

Making the Palace Machine Work Palace Machine the Making

11 ASIAN HISTORY Siebert, (eds) & Ko Chen Making the Machine Palace Work Edited by Martina Siebert, Kai Jun Chen, and Dorothy Ko Making the Palace Machine Work Mobilizing People, Objects, and Nature in the Qing Empire Making the Palace Machine Work Asian History The aim of the series is to offer a forum for writers of monographs and occasionally anthologies on Asian history. The series focuses on cultural and historical studies of politics and intellectual ideas and crosscuts the disciplines of history, political science, sociology and cultural studies. Series Editor Hans Hågerdal, Linnaeus University, Sweden Editorial Board Roger Greatrex, Lund University David Henley, Leiden University Ariel Lopez, University of the Philippines Angela Schottenhammer, University of Salzburg Deborah Sutton, Lancaster University Making the Palace Machine Work Mobilizing People, Objects, and Nature in the Qing Empire Edited by Martina Siebert, Kai Jun Chen, and Dorothy Ko Amsterdam University Press Cover illustration: Artful adaptation of a section of the 1750 Complete Map of Beijing of the Qianlong Era (Qianlong Beijing quantu 乾隆北京全圖) showing the Imperial Household Department by Martina Siebert based on the digital copy from the Digital Silk Road project (http://dsr.nii.ac.jp/toyobunko/II-11-D-802, vol. 8, leaf 7) Cover design: Coördesign, Leiden Lay-out: Crius Group, Hulshout isbn 978 94 6372 035 9 e-isbn 978 90 4855 322 8 (pdf) doi 10.5117/9789463720359 nur 692 Creative Commons License CC BY NC ND (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0) The authors / Amsterdam University Press B.V., Amsterdam 2021 Some rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, any part of this book may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise). -

Arresting Flows, Minting Coins, and Exerting Authority in Early Twentieth-Century Kham

Victorianizing Guangxu: Arresting Flows, Minting Coins, and Exerting Authority in Early Twentieth-Century Kham Scott Relyea, Appalachian State University Abstract In the late Qing and early Republican eras, eastern Tibet (Kham) was a borderland on the cusp of political and economic change. Straddling Sichuan Province and central Tibet, it was coveted by both Chengdu and Lhasa. Informed by an absolutist conception of territorial sovereignty, Sichuan officials sought to exert exclusive authority in Kham by severing its inhabitants from regional and local influence. The resulting efforts to arrest the flow of rupees from British India and the flow of cultural identity entwined with Buddhism from Lhasa were grounded in two misperceptions: that Khampa opposition to Chinese rule was external, fostered solely by local monasteries as conduits of Lhasa’s spiritual authority, and that Sichuan could arrest such influence, the absence of which would legitimize both exclusive authority in Kham and regional assertions of sovereignty. The intersection of these misperceptions with the significance of Buddhism in Khampa identity determined the success of Sichuan’s policies and the focus of this article, the minting and circulation of the first and only Qing coin emblazoned with an image of the emperor. It was a flawed axiom of state and nation builders throughout the world that severing local cultural or spiritual influence was possible—or even necessary—to effect a borderland’s incorporation. Keywords: Sichuan, southwest China, Tibet, currency, Indian rupee, territorial sovereignty, Qing borderlands On December 24, 1904, after an arduous fourteen-week journey along the southern road linking Chengdu with Lhasa, recently appointed assistant amban (Imperial Resident) to Tibet Fengquan reached Batang, a lush green valley at the western edge of Sichuan on the province’s border with central Tibet. -

340336 1 En Bookbackmatter 251..302

A List of Historical Texts 《安禄山事迹》 《楚辭 Á 招魂》 《楚辭注》 《打馬》 《打馬格》 《打馬錄》 《打馬圖經》 《打馬圖示》 《打馬圖序》 《大錢圖錄》 《道教援神契》 《冬月洛城北謁玄元皇帝廟》 《風俗通義 Á 正失》 《佛说七千佛神符經》 《宮詞》 《古博經》 《古今圖書集成》 《古泉匯》 《古事記》 《韓非子 Á 外儲說左上》 《韓非子》 《漢書 Á 武帝記》 《漢書 Á 遊俠傳》 《和漢古今泉貨鑒》 《後漢書 Á 許升婁傳》 《黃帝金匱》 《黃神越章》 《江南曲》 《金鑾密记》 《經國集》 《舊唐書 Á 玄宗本紀》 《舊唐書 Á 職官志 Á 三平准令條》 《開元別記》 © Springer Science+Business Media Singapore 2016 251 A.C. Fang and F. Thierry (eds.), The Language and Iconography of Chinese Charms, DOI 10.1007/978-981-10-1793-3 252 A List of Historical Texts 《開元天寶遺事 Á 卷二 Á 戲擲金錢》 《開元天寶遺事 Á 卷三》 《雷霆咒》 《類編長安志》 《歷代錢譜》 《歷代泉譜》 《歷代神仙通鑑》 《聊斋志異》 《遼史 Á 兵衛志》 《六甲祕祝》 《六甲通靈符》 《六甲陰陽符》 《論語 Á 陽貨》 《曲江對雨》 《全唐詩 Á 卷八七五 Á 司馬承禎含象鑒文》 《泉志 Á 卷十五 Á 厭勝品》 《勸學詩》 《群書類叢》 《日本書紀》 《三教論衡》 《尚書》 《尚書考靈曜》 《神清咒》 《詩經》 《十二真君傳》 《史記 Á 宋微子世家 Á 第八》 《史記 Á 吳王濞列傳》 《事物绀珠》 《漱玉集》 《說苑 Á 正諫篇》 《司馬承禎含象鑒文》 《私教類聚》 《宋史 Á 卷一百五十一 Á 志第一百四 Á 輿服三 Á 天子之服 皇太子附 后妃之 服 命婦附》 《宋史 Á 卷一百五十二 Á 志第一百五 Á 輿服四 Á 諸臣服上》 《搜神記》 《太平洞極經》 《太平廣記》 《太平御覽》 《太上感應篇》 《太上咒》 《唐會要 Á 卷八十三 Á 嫁娶 Á 建中元年十一月十六日條》 《唐兩京城坊考 Á 卷三》 《唐六典 Á 卷二十 Á 左藏令務》 《天曹地府祭》 A List of Historical Texts 253 《天罡咒》 《通志》 《圖畫見聞志》 《退宮人》 《萬葉集》 《倭名类聚抄》 《五代會要 Á 卷二十九》 《五行大義》 《西京雜記 Á 卷下 Á 陸博術》 《仙人篇》 《新唐書 Á 食貨志》 《新撰陰陽書》 《續錢譜》 《續日本記》 《續資治通鑑》 《延喜式》 《顏氏家訓 Á 雜藝》 《鹽鐵論 Á 授時》 《易經 Á 泰》 《弈旨》 《玉芝堂談薈》 《元史 Á 卷七十八 Á 志第二十八 Á 輿服一 儀衛附》 《雲笈七籖 Á 卷七 Á 符圖部》 《雲笈七籖 Á 卷七 Á 三洞經教部》 《韻府帬玉》 《戰國策 Á 齊策》 《直齋書錄解題》 《周易》 《莊子 Á 天地》 《資治通鑒 Á 卷二百一十六 Á 唐紀三十二 Á 玄宗八載》 《資治通鑒 Á 卷二一六 Á 唐天寶十載》 A Chronology of Chinese Dynasties and Periods ca. -

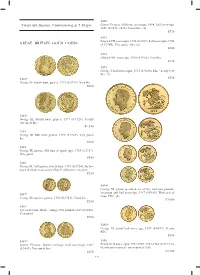

Twentieth Session, Commencing at 7.30 Pm GREAT BRITAIN GOLD

5490 Twentieth Session, Commencing at 7.30 pm Queen Victoria, old head, sovereign, 1898; half sovereign, 1896 (S.3874, 3878). Good fi ne. (2) $570 5491 Edward VII, sovereigns, 1905 (S.3969); half sovereigns, 1908 GREAT BRITAIN GOLD COINS (S.3974B). Very good - fi ne. (2) $500 5492 Edward VII, sovereign, 1910 (S.3969). Very fi ne. $370 5493 George V, half sovereigns, 1912 (S.4006). Fine - nearly very fi ne. (2) $350 5482* George III, fourth bust, guinea, 1774 (S.3728). Very fi ne. $600 5483* George III, fourth bust, guinea, 1777 (S.3728). Nearly extremely fi ne. $1,350 5484 George III, fi fth bust, guinea, 1787 (S.3729). Very good/ fi ne. $500 5485 George III, guinea, fi fth bust of spade type, 1788 (S.3729). Very good. $450 5486 George III, half guinea, fourth bust, 1781 (S.3734). Surface marked (from wear as jewellery?), otherwise very fi ne. $250 5494* George VI, proof specimen set of fi ve and two pounds, sovereign and half sovereign, 1937 (S.PS15). With case of 5487* issue, FDC. (4) George III, quarter guinea, 1762 (S.3741). Good fi ne. $7,000 $250 5488 Queen Victoria, Jubilee coinage, two pounds, 1887 (S.3865). Very good. $700 5495* George VI, proof half sovereign, 1937 (S.4077). Nearly FDC. $850 5489* 5496 Queen Victoria, Jubilee coinage, half sovereign, 1887 Elizabeth II, sovereigns, 1957-1959, 1962-1968 (S.4124, 5). (S.3869). Extremely fi ne. Nearly uncirculated - uncirculated. (10) $250 $3,700 532 5497 Elizabeth II, proof sovereigns, 1979 (S.4204) (2); proof half sovereigns, 1980 (S.4205) (2). -

Admiralty Dock 166 Agricultural Experimentation Site Nongshi

Index Admiralty Dock 166 Bishu shanzhuang 避暑山莊 88 Agricultural Experimentation Site nongshi bochuan剝船 125, 126 shiyan suo 農事實驗所 97 Bodde, Derk 295, 299 All-Hankou Guild Alliance Ge huiguan Bodolec, Caroline 28 各會館公所聯合會 gongsuo lianhe hui 327 bondservants 79, 82, 229, 264 Amelung, Iwo 88, 89 booi 264 American Banknote Company 237, 238 bound labour 60, 349 American Presbyterian Mission Press 253 Boxer Rebellion 143, 315, 356 Amoy. See Xiamen Bradstock, Timothy 327, 330, 331 潮州庵埠廠 Anfu, Chaozhou prefecture 188 brass utensils 95 Anhui 79, 120, 124, 132, 138, 139, 141, 172, 196, Bray, Francesca 25, 28, 317 249, 325, 342 bricklayers zhuanjiang 磚匠 91 安慶 Anqing 138 brickmakers 113 apprentices 99, 101, 102, 329, 333, 336, 337, 346 British Columbia 174 Arsenal 137, 146 brocade weavers 334 Arsenal wages 197, 199 Brokaw, Cynthia 28, 247, 248, 250, 251, 252, 255, artisan households 52 270, 274 artisan registration 94, 95 Brook, Timothy 62 匠体 artisan style jiangti 231 Bureau for Crafts gongyi ju 工藝局 97 Attiret, Denis 254, 269 Bureau for Weights and Measures quanheng Audemard 159, 169 duliang ju 權衡度量局 97 Auditing Office jieshen ku 節慎庫 75 Bureau of Construction yingshan qingli si 營繕 清吏司 74, 77, 106, 111, 335 baitang’a 栢唐阿 263 Bureau of Forestry and Weights yuheng qingli bang 幫 323, 331, 338, 342, 343 si 虞衡清吏司 74, 77 banner 263, 264, 265, 266, 267, 278 Bureau of Irrigation and Transportation dushui baofang 報房 234 qingli si 都水清吏司 75, 77 baogongzhi 包工制 196 Burger, Werner 28, 77 baogong 包工 112 Burgess, John S. 29, 326, 330, 336, 338 Baoquan ju 寳泉局 78, 107 -

Audited Consolidated Financial Statements WORLDWIDE ERC

Audited Consolidated Financial Statements WORLDWIDE ERC® March 31, 2019 Worldwide ERC® Contents Independent Auditor’s Report 1 - 2 Consolidated Financial Statements Consolidated statements of financial position 3 Consolidated statements of activities 4 Consolidated statements of cash flows 5 Notes to the consolidated financial statements 6 - 15 Independent Auditor’s Report To the Board of Directors Worldwide ERC®, Inc. We have audited the accompanying consolidated financial statements of Worldwide ERC®, Inc. (Worldwide ERC®), which comprise the consolidated statements of financial position as of March 31, 2019 and 2018, and the related consolidated statements of activities and cash flows for the years then ended, and the related notes to the consolidated financial statements. Management’s Responsibility for the Consolidated Financial Statements Management is responsible for the preparation and fair presentation of these consolidated financial statements in accordance with accounting principles generally accepted in the United States of America; this includes the design, implementation, and maintenance of internal control relevant to the preparation and fair presentation of consolidated financial statements that are free from material misstatement, whether due to fraud or error. Auditor’s Responsibility Our responsibility is to express an opinion on these consolidated financial statements based on our audits. We conducted our audits in accordance with auditing standards generally accepted in the United States of America. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain reasonable assurance about whether the consolidated 2 0 2 1 L S t r e e t, N W financial statements are free from material misstatement. An audit involves performing procedures to obtain audit evidence about the amounts and disclosures in the consolidated financial statements. -

The Wonderful World of Trade Dollars

The Wonderful World of Trade Dollars Lecture Set #34 Project of the Verdugo Hills Coin Club Photographed by John Cork & Raymond Reingohl Introduction Trade Dollars in this presentation are grouped into 3 categories • True Trade Dollars • It was intended to circulate in remote areas from its minting source • Accepted Trade Dollars • Trade dollar’s value was highly accepted for trading purposes in distant lands • Examples are the Spanish & Mexican 8 Reales and the Maria Theresa Thaler • Controversial Trade Dollars • A generally accepted dollar but mainly minted to circulate in a nation’s colonies • Examples are the Piastre de Commerce and Neu Guinea 5 Marks This is the Schlick Guldengroschen, commonly known as the Joachimstaler because of the large silver deposits found in Bohemia; now in the Czech Republic. The reverse of the prior two coins. Elizabeth I authorized this Crown This British piece created to be used by the East India Company is nicknamed the “Porticullis Crown” because of the iron grating which protected castles from unauthorized entry. Obverse and Reverse of a Low Countries (Netherlands) silver Patagon, also called an “Albertus Taler.” Crown of the United Amsterdam Company 8 reales issued in 1601 to facilitate trade between the Dutch and the rest of Europe. Crown of the United Company of Zeeland, minted at Middleburg in 1602, similar in size to the 8 reales. This Crown is rare and counterfeits have been discovered to deceive the unwary. The Dutch Leeuwendaalder was minted for nearly a century and began as the common trade coin from a combination of all the Dutch companies which fought each other as well as other European powers.