Panel Requested Documents

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

LGWM – Strategic Context

LGWM – Strategic Context 9 November 2017 Executive Summary Purpose Let’s Get Wellington Moving (LGWM) is a joint initiative by Wellington City Council, Greater Wellington Regional Council and the New Zealand Transport Agency (the Transport Agency). LGWM is investigating the merits of investing in the transport system to improve outcomes for Wellington, with a focus on the area from Ngauranga to the airport, including the central city. This paper outlines the transport, land use and other contexts within which the LGWM programme is set. It also describes the range of strategic transport improvements being progressed or planned across the region that are not within the scope of the LGWM programme but are important complementary initiatives. Background Our region is growing, with between 100,000 and 150,000 more people expected to live here 30 years from now. More than half will live in Wellington City, and the fastest growing areas will be in and around the central city. Wellington City is expected to remain the key regional economic centre, with 80% of the region’s employment growth. Much of the peak travel demand by commuters will likely continue to be on corridors and routes to and from central Wellington. Wellington’s compact form supports an effective public transport network and high public transport use. However, overall transport capacity is constrained by narrow transport corridors that increase conflict between transport modes. Limited capacity and connections between local roads and arterial routes beyond the CBD also make the transport network vulnerable to disruptions. A number of critical lifeline locations are situated in the LGWM project area, including Wellington Regional Hospital and Wellington International Airport. -

Secondary Schools of New Zealand

All Secondary Schools of New Zealand Code School Address ( Street / Postal ) Phone Fax / Email Aoraki ASHB Ashburton College Walnut Avenue PO Box 204 03-308 4193 03-308 2104 Ashburton Ashburton [email protected] 7740 CRAI Craighead Diocesan School 3 Wrights Avenue Wrights Avenue 03-688 6074 03 6842250 Timaru Timaru [email protected] GERA Geraldine High School McKenzie Street 93 McKenzie Street 03-693 0017 03-693 0020 Geraldine 7930 Geraldine 7930 [email protected] MACK Mackenzie College Kirke Street Kirke Street 03-685 8603 03 685 8296 Fairlie Fairlie [email protected] Sth Canterbury Sth Canterbury MTHT Mount Hutt College Main Road PO Box 58 03-302 8437 03-302 8328 Methven 7730 Methven 7745 [email protected] MTVW Mountainview High School Pages Road Private Bag 907 03-684 7039 03-684 7037 Timaru Timaru [email protected] OPHI Opihi College Richard Pearse Dr Richard Pearse Dr 03-615 7442 03-615 9987 Temuka Temuka [email protected] RONC Roncalli College Wellington Street PO Box 138 03-688 6003 Timaru Timaru [email protected] STKV St Kevin's College 57 Taward Street PO Box 444 03-437 1665 03-437 2469 Redcastle Oamaru [email protected] Oamaru TIMB Timaru Boys' High School 211 North Street Private Bag 903 03-687 7560 03-688 8219 Timaru Timaru [email protected] TIMG Timaru Girls' High School Cain Street PO Box 558 03-688 1122 03-688 4254 Timaru Timaru [email protected] TWIZ Twizel Area School Mt Cook Street Mt Cook Street -

Hearing Transcript Day 21.Pdf

TRANSCRIPT OF PROCEEDINGS BOARD OF INQUIRY MacKays to Peka Peka Expressway Proposal HEARING at KAPITI COAST on 10 JANUARY 2013 BOARD OF INQUIRY: Sir John Hansen (Chairperson) Environment Commissioner David Bunting (Board Member) Ms Glenice Paine (Board Member) Mr Mark Apeldoorn (Board Member) Page 1897 [9.31 am] CHAIRPERSON: Thank you. Just before we call Mr Gross and Mr Gray, 5 Commissioner Bunting has indicated that he worked in the same organisation as Mr Gray many years ago. He identified that to the Board beforehand and, just for the record, we are satisfied there is no conflict of interest involved. So Mr Gross and Mr Gray if you would come forward please. 10 MR GROSS: Sir John, commissioners, my name is Michael Gross, I am currently chairperson of the Wellington District of the New Zealand Automobile Association. I have a background in local government, I chaired various local, regional and national bodies of local government 15 during the 1980s and 1990s and was spokesman for the New Zealand Local Government Association on transport issues at that time. After I exited local government in 1995 I was the establishment chair of the Transfund board and chaired that organisation for seven of its 20 nine years until policy changes saw it re-amalgamated with the Safety Authority and later, of course, morphed into the New Zealand Transport Agency as we have today. I have with me Mr Alex Gray who is an engineer who has spent a 25 career in major infrastructure projects around the Wellington region and he will largely present our submission. -

Background and Issues Paper 2010

Hutt Corridor Plan Review Background and Issues Paper 2010 Important Note: This is a working paper, the purpose of which was to pull together a range of relevant information and statistics, and to identify relevant studies and policies, to assist the technical group in understanding the current context for the Hutt Corridor Plan review. The information and numbers generally reflect what was available during the earlier stages of the plan’s development during 2010. Significant recent updates on project status are noted throughout the paper. Where newer stats or data have become available since this paper was prepared, it has been used directly in the Draft Plan itself. PAGE 1 OF 105 PAGE 2 OF 105 Contents INTRODUCTION..................................................................................................................6 POLICY CONTEXT FOR THE CORRIDOR PLAN REVIEW ...............................................9 1. National context ........................................................................................................................................................9 1.1 New Zealand Transport Strategy 2008..............................................................................................................9 1.2 Government Policy Statement (GPS) on Land Transport Funding...................................................................9 1.3 Safer Journeys 2020 ........................................................................................................................................10 1.4 NZ -

Lake Tekapo to Twizel Highlights

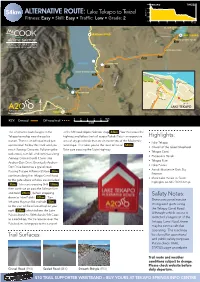

AORAKI/MT COOK WHITE HORSE HILL CAMPGROUND MOUNT COOK VILLAGE BURNETT MOUNTAINS MOUNT COOK AIRPORT TASMAN POINT Tasman Valley Track FRED’S STREAM TASMAN RIVER JOLLIE RIVER SH80 Jollie Carpark Braemar-Mount Cook Station Rd 800 TEKAPO TWIZEL 700 54km ALTERNATIVEGLENTANNER PARK CENTRE ROUTE: Lake Tekapo to Twizel 600 LANDSLIP CREEK ELEVATION Fitness: Easy • Skill: Easy • Traffic: Low • Grade: 2 500 400 KM LAKE PUKAKI 0 10 20 30 40 50 MT JOHN OBSERVATORY LAKE TEKAPO BRAEMAR ROAD Tekapo Powerhouse Rd LAKE TEKAPO TEKAPO A POWER STATION SH8 3km TRAIL GUARDIAN Hayman Rd SALMON FARM TO SALMON SHOP Tekapo Canal Rd PATTERSONS PONDS 9km TEKAPO CANAL 15km Tekapo Canal Rd LAKE PUKAKI SALMON FARM 24km TEKAPO RIVER TEKAPO B POWER STATION Hayman Road LAKE TEKAPO 30km Lakeside Dr Te kapo-Twizel Rd Church of the 8 Good Shepherd Dog Monument MARY RANGES SH80 35km r s D TEKAPO RIVERe SH8 r r 44km C e i e Pi g n on n Roto Pl o i e a e P SALMON SHOP r r D o r A Scott Pond Aorangi Cres 8 PUKAKI CANAL SH8 F Rd airlie-Tekapo PUKAKI RIVER Allan St Glen Lyon Rd Glen Lyon Rd LAKE TEKAPO Andrew Don Dr Old Glen Lyon Rd Pukaki Flats Track Murray Pl TWIZEL PUKAKI FLATS Mapwww.alps2ocean.com current as of 28/7/17 N 54km OHAU CANAL LAKE RUATANIWHA 0 1 2 3 4 5km KEY: Onroad Off-road trail SH8 Scale The alternative route begins in the at the Mt Cook Alpine Salmon shop 44km . You then cross the Tekapo township near the police highway and follow the trail across Pukaki Flats – an expansive Highlights: station. -

Middle Earth: Hobbit & Lord of the Rings Tour

MIDDLE EARTH: HOBBIT & LORD OF THE RINGS TOUR 16 DAY MIDDLE EARTH: HOBBIT & LORD OF THE RINGS TOUR YOUR LOGO PRICE ON 16 DAYS MIDDLE EARTH: HOBBIT & LORD OF THE RINGS TOUR REQUEST Day 1 ARRIVE AUCKLAND Day 5 OHAKUNE / WELLINGTON Welcome to New Zealand! We are met on arrival at Auckland This morning we drive to the Mangawhero Falls and the river bed where International Airport before being transferred to our hotel. Tonight, a Smeagol chased and caught a fish, before heading south again across the welcome dinner is served at the hotel. Central Plateau and through the Manawatu Gorge to arrive at the garden of Fernside, the location of Lothlorién in Featherston. Continue south Day 2 AUCKLAND / WAITOMO CAVES / HOBBITON / ROTORUA before arriving into New Zealand’s capital city Wellington, home to many We depart Auckland and travel south crossing the Bombay Hills through the of the LOTR actors and crew during production. dairy rich Waikato countryside to the famous Waitomo Caves. Here we take a guided tour through the amazing limestone caves and into the magical Day 6 WELLINGTON Glowworm Grotto – lit by millions of glow-worms. From Waitomo we travel In central Wellington we walk to the summit of Mt Victoria (Outer Shire) to Matamata to experience the real Middle-Earth with a visit to the Hobbiton and visit the Embassy Theatre – home to the Australasian premieres of Movie Set. During the tour, our guides escorts us through the ten-acre site ‘The Fellowship of the Ring’ and ‘The Two Towers’ and world premiere recounting fascinating details of how the Hobbiton set was created. -

NZFSS Newsletter 51 (2012)

New Zealand Freshwater Sciences Society Newsletter Number 51 • December0 | P a g e 2012 ISSN 1177-2026 (print) • ISSN 1178-6906 (online) Contents 1 Introduction to the society .................................................................................................................... 3 2 Editorial .................................................................................................................................................. 5 3 President’s piece .................................................................................................................................... 7 4 He Maimai Aroha – Farewells ................................................................................................................ 9 4 Invited articles and opinion pieces ...................................................................................................... 11 4.1 Prorhynchus putealis: range expansion and call for observations ............................................. 11 4.2 Stealthily slaying the RMA? ......................................................................................................... 14 4.3 A ‘New Deal’ for Fresh Water ..................................................................................................... 15 4.4 A new record for Campbell Island ............................................................................................... 17 4.5 World Class Water and Wildlife ................................................................................................. -

Enhancing the Conservation Value of the Birchwood Wetland

Enhancing the Conservation Value of the Birchwood Wetland Robyn Newham and Courtney Quirin A report submitted in partial fulfilment of the Post-graduate Diploma in Wildlife Management University of Otago Year 2007 University of Otago Department of Zoology P.O. Box 56, Dunedin New Zealand WLM Report Number: 203 Enhancing the Conservation Value of the Birchwood Wetland Robyn Newham Courtney Quirin 1 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The Birchwood wetland area has recently been included within the Ahuriri Conservation Park in the MacKenzie Basin, South Island, New Zealand. The wetland area is ranked as an ‘outstanding’ site of wildlife interest, providing breeding grounds for black stilt, black-fronted tern, large wrybill and Australian bittern populations, in addition to providing essential habitat for other waterfowl. However, past anthropogenic activities, such as drainage, recreation and introduced species, have degraded the Birchwood wetland. The aims of this research and management proposal attempt to increase the productivity of the wetland system, which serves to expand and improve the suitability of habitat for target birds and to enhance the awareness of the public through conservation education. Our research and management plan draws on past wetland enhancement strategies, in addition to incorporating site specific data and original thought. Recommendations A combined ecological and social approach to the management of the Birchwood wetland was proposed. ECOLOGICAL o Due to the complete lack of information about the ecological processes within the wetland, intensive research of the hydrology, geology, invertebrate and vegetation composition was recommended. o Research is critical as modification to the landscape and system may have serious long-term consequences to the Birchwood wetland and neighboring ecological systems. -

SIRG Ruapehu

Snow and Ice Research Group (SIRG) New Zealand Annual Workshop Mt Ruapehu 12th to 14th February 2007 Ruapehu Crater Lake from Tahurangi (2797m). Photo by Andrew Mackintosh PRESENTATION TIMETABLE Time Presenter Topic Monday 2:00 Heather and Welcome & Introduction Andrew 2:15 Trevor Chinn Glacier Mass Balance Measurements in N.Z. History and Development 2:30 Jordy Hendrix (for Glacier volume changes in the Southern Alps - Trends and Jim Salinger) variations from snowline monitoring 2:45 Andrew On the response of maritime glaciers to climatic change Mackintosh 3:00 Afternoon tea 3:30 Dorothea Stumm Index-stake Mass-balance measurements on Rolleston Glacier 3:45 Pascal Sirguey Operational and Improved Snow Mapping at Subpixel resolution in the Waitaki Basin using MODIS/TERRA 4:00 Tim Kerr Comparison of CROSS-Mountain precipitation profiles from around the world 4:15 Brian Anderson Response of KA ROIMATA O HINE HUKATERE Franz Josef Glacier to Climate Change 4:30 Uwe Morgenstern Ice dating on Tasman, Franz-Josef and Fox Glaciers 4:45 Simon Allen Geomorphic Hazard Modelling in the Mount Cook Region: Initial Results from ASTER based Glacial Lake MAPPING 5:00 Wolfgang Rack Tidal flexure and ice flux in the grounding zone of Jutulstraumen, Antarctica 7.00 pm Dinner at Lodge 8.00 pm Harry Keys After dinner talk about Mt Ruapehu Tuesday or Wednesday depending on weather 8:30 Shelly McDonnell Drainage system development of the Wright Lower Glacier, Antarctica, over a season 8:45 Martin Brook Late Quaternary glacial history of Mt Allen, southern Stewart -

Twizel Highlights

FAIRLIE | LAKE TEKAPO | AORAKI / MOUNT COOK | TWIZEL HIGHLIGHTS FAIRLIE Explore local shops | Cafés KIMBELL Walking trails | Art gallery BURKES PASS Shopping & art | Heritage walk | Historic Church LAKE TEKAPO Iconic Church | Walks/trails LAKE PUKAKI Beautiful scenery | Lavender farm GLENTANNER Beautiful vistas | 18kms from Aoraki/Mount Cook Village AORAKI/MOUNT COOK Awe-inspiring mountain views | Adventure playground TWIZEL Quality shops | Eateries | Five lakes nearby | Cycling Welcome to the Mackenzie Region The Mackenzie Region spaces are surrounded by SUMMER provides many WINTER in the Mackenzie winter days are perfect is located at the heart snow-capped mountains, experiences interacting is unforgettable with for scenic flights and the p18 FAIRLIE of New Zealand’s South including New Zealand’s with the natural landscape uncrowded snow fields and nights crisp and clear for Island, 2.5 hour’s drive from tallest, Aoraki/Mount Cook, of our unique region, from unique outdoor experiences spectacular stargazing. Christchurch or 3 hours from with golden tussocks giving star gazing tours and scenic as well as plenty of ways p20 LAKE TEKAPO Be spoilt for choice Dunedin/Queenstown. way to turquoise-blue lakes, flights, to hot pools and to relax after a day on the with a wide variety of Explore one of the most fed by meltwater from cycle trails. Check out 4WD slopes. Ride the snow tube, accommodation styles, eat picturesque regions offering numerous glaciers. tours, farm tours and boating visit our family friendly snow local cuisine, and smile at p30 AORAKI/MOUNT COOK bright, sunny days and dark experiences or get your fields or relax in the hot pools. -

Very Wet in Many Parts and an Extremely Cold Snap for the South

New Zealand Climate Summary: June 2015 Issued: 3 July 2015 Very wet in many parts and an extremely cold snap for the south. Rainfall Rainfall was above normal (120-149%) or well above normal (> 149%) for much of the Manawatu-Whanganui, Taranaki, Westland, Tasman, Nelson, Marlborough, Canterbury, Otago, and Southland regions. Rainfall was well below normal (< 50%) or below normal (50-79%) for parts of Northland, Auckland, Waikato, Bay of Plenty, Gisborne, Hawke’s Bay, and north Canterbury. Temperature June temperatures were near average across much of the country (within 0.5°C of June average). Below average temperatures were recorded in inland Canterbury, Wairarapa, western Waikato (0.5-1.2°C below June average) and above average temperatures experienced in northern, eastern, and western parts of the North Island and northern, western, and south-central parts of the South Island (0.5-1.2°C above June average). A polar outbreak in late June led to the 4th-lowest temperature ever recorded in New Zealand. Soil Moisture As of 1 July 2015, soil moisture levels were below normal for this time of year for East Cape, around and inland from Napier, coastal Wairarapa, coastal southern Marlborough and eastern parts of Canterbury north of Christchurch. It was especially dry about north Canterbury where soils were considerably drier than normal for this time of year. Sunshine Well above normal (>125%) or above normal (110-125%) sunshine was recorded in Northland, Auckland, western Waikato, Wellington, Marlborough, north Canterbury, and Central Otago. Near normal sunshine (within 10% of normal) was recorded elsewhere, expect in Franz Josef and Tauranga where below normal sunshine was recorded. -

Western Corridor Plan Adopted August 2012 Western Corridor Plan 2012 Adopted August 2012

Western Corridor Plan Adopted August 2012 Western Corridor Plan 2012 Adopted August 2012 For more information, contact: Greater Wellington Published September 2012 142 Wakefield Street GW/CP-G-12/226 PO Box 11646 Manners Street [email protected] Wellington 6142 www.gw.govt.nz T 04 384 5708 F 04 385 6960 Western Corridor Plan Strategic Context Corridor plans organise a multi-modal response across a range of responsible agencies to the meet pressures and issues facing the region’s land transport corridors over the next 10 years and beyond. The Western Corridor generally follows State Highway 1 from the regional border north of Ōtaki to Ngauranga and the North Island Main Trunk railway to Kaiwharawhara. The main east- west connections are State Highway 58 and the interchange for State Highways 1 and 2 at Ngauranga. Long-term vision This Corridor Plan has been developed to support and contribute to the Regional Land Transport Strategy (RLTS), which sets the objectives and desired outcomes for the region’s transport network. The long term vision in the RLTS for the Western Corridor is: Along the Western Corridor from Ngauranga to Traffic congestion on State Highway 1 will be Ōtaki, State Highway 1 and the North Island Main managed at levels that balance the need for access Trunk railway line will provide a high level of access against the ability to fully provide for peak demands and reliability for passengers and freight travelling due to community impacts and cost constraints. within and through the region in a way which Maximum use of the existing network will be achieved recognises the important strategic regional and by removal of key bottlenecks on the road and rail national role of this corridor.