47 West 28Th Street Building, Tin Pan Alley

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Our Boys : a Comedy in Three Acts

^“.“LesUbranf Sciences fcrts & Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2016 https://archive.org/details/ourboyscomedyint00byro_0 IVv \ [jiw y\ 7 1 >t ir? f i/wjMr'.' ' v'-’ Vi lliahVarren EDITION OF- STANDARD • PLAYS OUR. BOYS VALTER H .BAKER & CO. N X} HAM I LTOM • PLACE BOSTON a. W, ^laj>3 gBrice, 50 €entg €acl) TH£ AMAZONS ^arce * n Three Acts. Seven males, five females. Costumes, modern ; scenery, not difficult. Plays a full evening. THE CABINET MINISTER in Four Acts. Ten males, nine females. Costumes, modern society ; scenery, three interiors. Plays a full evening. in Three DANDY DICK Farce Acts. Se\en males, four females. Costumes, modern ; scenery, two interiors. Plays two hours and a half. Comedy in Four Acts. Four males, ten THE GAY LORD OUEX^ females. Costumes, modern ; scenery, two interiors and an exterior. Plays a full evening. Comedy in Four Acts. .Nine males, four BIS BOUSE IN ORDER ' females. Costumes, modern scenery, ; three interiors. Plays a full evening. ^ome<i ^ Three Acts. Ten males, five THE HOBBY HOBSE ^ females. Costumes, modern; scenery easy. Plays two hours and a half. ^rama ^ Five Acts. Seven males, seven females. Costumes, IRIS modern ; scenery, three interiors. Plays a full evening. Flay *n Four Acts. Eight males, seven fe- I A R0I1NTIFITI ** BY ** males. Costumes, modern ; scenery, four in- teriors, not easy. Plays a full evening. T>rama in Four Acts and an Epilogue. Ten males, five fe- I FTTY ** males. Costumes, modern ; scenery complicated. Plays a full evening Sent prepaid on receipt of price by Waltn % oaafeet & Company No. 5 Hamilton Place, Boston, Massachusetts OUR BOYS A Comedy in Three Acts By HENRY J. -

Finding Aid for the Sheldon Harris Collection (MUM00682)

University of Mississippi eGrove Archives & Special Collections: Finding Aids Library November 2020 Finding Aid for the Sheldon Harris Collection (MUM00682) Follow this and additional works at: https://egrove.olemiss.edu/finding_aids Recommended Citation Sheldon Harris Collection, Archives and Special Collections, J.D. Williams Library, The University of Mississippi This Finding Aid is brought to you for free and open access by the Library at eGrove. It has been accepted for inclusion in Archives & Special Collections: Finding Aids by an authorized administrator of eGrove. For more information, please contact [email protected]. University of Mississippi Libraries Finding aid for the Sheldon Harris Collection MUM00682 TABLE OF CONTENTS SUMMARY INFORMATION Summary Information Repository University of Mississippi Libraries Biographical Note Creator Scope and Content Note Harris, Sheldon Arrangement Title Administrative Information Sheldon Harris Collection Related Materials Date [inclusive] Controlled Access Headings circa 1834-1998 Collection Inventory Extent Series I. 78s 49.21 Linear feet Series II. Sheet Music General Physical Description note Series III. Photographs 71 boxes (49.21 linear feet) Series IV. Research Files Location: Blues Mixed materials [Boxes] 1-71 Abstract: Collection of recordings, sheet music, photographs and research materials gathered through Sheldon Harris' person collecting and research. Prefered Citation Sheldon Harris Collection, Archives and Special Collections, J.D. Williams Library, The University of Mississippi Return to Table of Contents » BIOGRAPHICAL NOTE Born in Cleveland, Ohio, Sheldon Harris was raised and educated in New York City. His interest in jazz and blues began as a record collector in the 1930s. As an after-hours interest, he attended extended jazz and blues history and appreciation classes during the late 1940s at New York University and the New School for Social Research, New York, under the direction of the late Dr. -

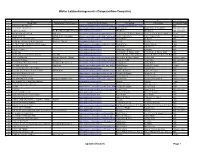

EXCEL LATZKO MUZIK CATALOG for PDF.Xlsx

Walter Latzko Arrangements (Computer/Non-Computer) A B C D E F 1 Song Title Barbershop Performer(s) Link or E-mail Address Composer Lyricist(s) Ensemble Type 2 20TH CENTURY RAG, THE https://www.sheetmusicplus.com/title/the-20th-century-rag-digital-sheet-music/21705300 Male 3 "A"-YOU'RE ADORABLE www.sheetmusicplus.com/title/a-you-re-adorable-digital-sheet-music/21690032Sid Lippman Buddy Kaye & Fred Wise Male or Female 4 A SPECIAL NIGHT The Ritz;Thoroughbred Chorus [email protected] Don Besig Don Besig Male or Female 5 ABA DABA HONEYMOON Chordettes www.sheetmusicplus.com/title/aba-daba-honeymoon-digital-sheet-music/21693052Arthur Fields & Walter Donovan Arthur Fields & Walter Donovan Female 6 ABIDE WITH ME Buffalo Bills; Chordettes www.sheetmusicplus.com/title/abide-with-me-digital-sheet-music/21674728Henry Francis Lyte Henry Francis Lyte Male or Female 7 ABOUT A QUARTER TO NINE Marquis https://www.sheetmusicplus.com/title/about-a-quarter-to-nine-digital-sheet-music/21812729?narrow_by=About+a+Quarter+to+NineHarry Warren Al Dubin Male 8 ACADEMY AWARDS MEDLEY (50 songs) Montclair Chorus [email protected] Various Various Male 9 AC-CENT-TCHU-ATE THE POSITIVE (5-parts) https://www.sheetmusicplus.com/title/ac-cent-tchu-ate-the-positive-digital-sheet-music/21712278Harold Arlen Johnny Mercer Male 10 ACE IN THE HOLE, THE [email protected] Cole Porter Cole Porter Male 11 ADESTES FIDELES [email protected] John Francis Wade unknown Male 12 AFTER ALL [email protected] Ervin Drake & Jimmy Shirl Ervin Drake & Jimmy Shirl Male 13 AFTER THE BALL/BOWERY MEDLEY Song Title [email protected] Charles K. -

IN NEW YORK CITY January/February/March 2019 Welcome to Urban Park Outdoors in Ranger Facilities New York City Please Call Specific Locations for Hours

OutdoorsIN NEW YORK CITY January/February/March 2019 Welcome to Urban Park Outdoors in Ranger Facilities New York City Please call specific locations for hours. BRONX As winter takes hold in New York City, it is Pelham Bay Ranger Station // (718) 319-7258 natural to want to stay inside. But at NYC Pelham Bay Park // Bruckner Boulevard Parks, we know that this is a great time of and Wilkinson Avenue year for New Yorkers to get active and enjoy the outdoors. Van Cortlandt Nature Center // (718) 548-0912 Van Cortlandt Park // West 246th Street and Broadway When the weather outside is frightful, consider it an opportunity to explore a side of the city that we can only experience for a few BROOKLYN months every year. The Urban Park Rangers Salt Marsh Nature Center // (718) 421-2021 continue to offer many unique opportunities Marine Park // East 33rd Street and Avenue U throughout the winter. Join us to kick off 2019 on a guided New Year’s Day Hike in each borough. This is also the best time to search MANHATTAN for winter wildlife, including seals, owls, Payson Center // (212) 304-2277 and eagles. Kids Week programs encourage Inwood Hill Park // Payson Avenue and families to get outside and into the park while Dyckman Street school is out. This season, grab your boots, mittens, and QUEENS hat, and head to your nearest park! New York Alley Pond Park Adventure Center City parks are open and ready to welcome you (718) 217-6034 // (718) 217-4685 year-round. Alley Pond Park // Enter at Winchester Boulevard, under the Grand Central Parkway Forest Park Ranger Station // (718) 846-2731 Forest Park // Woodhaven Boulevard and Forest Park Drive Fort Totten Visitors Center // (718) 352-1769 Fort Totten Park // Enter the park at fort entrance, north of intersection of 212th Street and Cross Island Parkway and follow signs STATEN ISLAND Blue Heron Nature Center // (718) 967-3542 Blue Heron Park // 222 Poillon Ave. -

Return of Organization Exempt from Income

efile GRAPHIC p rint - DO NOT PROCESS As Filed Data - DLN: 93493321035384 Return of Organization Exempt From Income Tax OMB No 1545-0047 Form 990 Under section 501 ( c), 527, or 4947 ( a)(1) of the Internal Revenue Code ( except private foundations) 2O1 3 Do not enter Social Security numbers on this form as it may be made public By law, the IRS Department of the Treasury Open generally cannot redact the information on the form Internal Revenue Service Inspection - Information about Form 990 and its instructions is at www.IRS.gov/form990 For the 2013 calendar year, or tax year beginning 06-01-2013 , 2013, and ending 05-31-2014 C Name of organization B Check if applicable D Employer identification number EQUITY LEAGUE HEALTH TRUST FUND f Address change 13-6092981 Doing Business As • Name change fl Initial return Number and street (or P 0 box if mail is not delivered to street address) Room/suite E Telephone number 165 WEST 46TH STREET 14TH FLOOR p Terminated (212)869-9380 (- Amended return City or town, state or province, country, and ZIP or foreign postal code NEW YORK, NY 10036 1 Application pending G Gross receipts $ 104,708,930 F Name and address of principal officer H(a) Is this a group return for Arthur Drechsler subordinates? 1 Yes F No H(b) Are all subordinates 1 Yes F No included? I Tax-exempt status F_ 501(c)(3) F 501(c) ( 9 I (insert no (- 4947(a)(1) or F_ 527 If "No," attach a list (see instructions) J Website : - www equityleague org H(c) Group exemption number 0- K Form of organization 1 Corporation 1 Trust F_ Association (- Other 0- L Year of formation 1960 M State of legal domicile NY Summary 1 Briefly describe the organization's mission or most significant activities TO PROVIDE HEALTH AND OTHER BENEFITS TO ELIGIBLE PARTICIPANTS w 2 Check this box Of- if the organization discontinued its operations or disposed of more than 25% of its net assets 3 Number of voting members of the governing body (Part VI, line 1a) . -

D. Rail Transit

Chapter 9: Transportation (Rail Transit) D. RAIL TRANSIT EXISTING CONDITIONS The subway lines in the study area are shown in Figures 9D-1 through 9D-5. As shown, most of the lines either serve only portions of the study area in the north-south direction or serve the study area in an east-west direction. Only one line, the Lexington Avenue line, serves the entire study area in the north-south direction. More importantly, subway service on the East Side of Manhattan is concentrated on Lexington Avenue and west of Allen Street, while most of the population on the East Side is concentrated east of Third Avenue. As a result, a large portion of the study area population is underserved by the current subway service. The following sections describe the study area's primary, secondary, and other subway service. SERVICE PROVIDED Primary Subway Service The Lexington Avenue line (Nos. 4, 5, and 6 routes) is the only rapid transit service that traverses the entire length of the East Side of Manhattan in the north-south direction. Within Manhattan, southbound service on the Nos. 4, 5 and 6 routes begins at 125th Street (fed from points in the Bronx). Local service on the southbound No. 6 route ends at the Brooklyn Bridge station and the last express stop within Manhattan on the Nos. 4 and 5 routes is at the Bowling Green station (service continues into Brooklyn). Nine of the 23 stations on the Lexington Avenue line within Manhattan are express stops. Five of these express stations also provide transfer opportunities to the other subway lines within the study area. -

The New York City Subway

John Stern, a consultant on the faculty of the not-for-profit Aesthetic Realism Foundation in New York City, and a graduate of Columbia University, has had a lifelong interest in architecture, history, geology, cities, and transportation. He was a senior planner for the Tri-State Regional Planning Commission in New York, and is an Honorary Director of the Shore Line Trolley Museum in Connecticut. His extensive photographs of streetcar systems in dozens of American and Canadian cities during the late 1940s, '50s, and '60s comprise a major portion of the Sprague Library's collection. Mr. Stern resides in New York City with his wife, Faith, who is also a consultant of Aesthetic Realism, the education founded by the American poet and critic Eli Siegel (1902-1978). His public talks include seminars on Fiorello LaGuardia and Robert Moses, and "The Brooklyn Bridge: A Study in Greatness," written with consultant and art historian Carrie Wilson, which was presented at the bridge's 120th anniversary celebration in 2003, and the 125th anniversary in 2008. The paper printed here was given at the Aesthetic Realism Foundation, 141 Greene Street in NYC on October 23rd and at the Queens Public Library in Flushing in 2006. The New York Subway: A Century By John Stern THURSDAY, OCTOBER 27, 1904 was a gala day in the City of New York. Six hundred guests assembled inside flag-bedecked City Hall listened to speeches extolling the brand-new subway, New York's first. After the last speech, Mayor George B. McClellan spoke, saying, "Now I, as Mayor, in the name of the people, declare the subway open."1 He and other dignitaries proceeded down into City Hall station for the inau- gural ride up the East Side to Grand Central Terminal, then across 42nd Street to Times Square, and up Broadway to West 145th Street: 9 miles in all (shown by the red lines on the map). -

Not Be Fouud by at Least Three of the Inspectors"

I j. f? 6 NEW YOEK HERALD, THURSDAt. OCTOBKK % Ib79..TKU'JLE SHEET. State in the election. d'Etat. self and for himself in a barrel all around Btinot.has been the of The New Folltieal Firm.Kelly, the equal advantages Mayor Coupor'n Coup outgrowth should have one-fourth of the circle, 'l'ho Herald at tbo time warned afforded tho Mr. Thomas and NEW YORK HERALD & Co. But if Tammany "It is the uuoxpocte 1 that happens," public by opportunities Cornellthe there would be least the and of all these bis ooluborors in this field of music during in the Police lioard inspectors virtually says a French proverb; bat among the proprietors supportors AND ANN STREET. The pending struggle three Cornell in each district that booms that they were making the post twenty years. Our German BROADWAY of of iuspeotors expected and most surprising tilings simply over the appointment inspector* one ltobinson sinoe the ridiculous and that each and every musical.have fostered and chief ugaiust inspector, could have happened is Mayor Cooper's themselves residents.largely continues to be the politicalelection and avowed of the vote one of them was marked for an kept alive in their homes the lovo of JAMES GORDON BENNETT, have solo purpose Kelly to remove from the Polioe Board hisattempt early grave. enough our uorr.ii:To». topic, although inspectors is to elect Cornell. own of Messrs. The first frost has scaroely come and tho old masters, and formed a to conduct the appointees, two whom, they been appointed legally The order of Barrett the and have been his servile prediction has been fulfilled. -

WINTER 2017 5 Note from the Editor by Kim Decoste, Editor of the VOICE Magazine

Election Perspective: History and the Future pg . 35 ALSO IN THIS ISSUE: A Little Goes a Long Way- This Year’s Soldiers Angels Program pg. 6 TREA Membership Perks pg. 28 Let Us Remember and Honor Our World War II Missing pg. 38 YOUR USAA REWARDS™ CREDIT CARD NOW OFFERS MORE WAYS TO GIVE BACK. Donate your USAA Rewards credit card points to the The ENLISTED Association and help support their mission. Each point donated is transferred to a monetary contribution; every 1,000 rewards points equals $10. Donate Today. USAA.COM/POINTSDONATION USAA means United Services Automobile Association and its affiliates. USAA products are available only in those jurisdictions where USAA is authorized to sell them. Use of the term “member” or “membership” does not convey any eligibility rights for auto and property insurance products, or legal or ownership rights in USAA. Membership eligibility and product restrictions apply and are subject to change. Purchase of a product other than USAA auto or property insurance, or purchase of an insurance policy offered through the USAA Insurance Agency, does not establish eligibility for, or membership in, USAA property and casualty insurance companies. The ENLISTED Association receives financial support from USAA for this sponsorship. 2 This credit card program is issued by USAA Savings Bank, Member FDIC. © 2016 USAA. 231789-0716 The VOICE is the flagship publication of TREA: The En- YOUR USAA REWARDS™ listed Association, located at 1111 S. Abilene Ct., Aurora, CO 80012. CREDIT CARD NOW OFFERS Views expressed in the magazine, and the appearance of advertisement, do not necessarily reflect the opinions of TABLE OF CONTENTS TREA or its board of directors, and do not imply endorse- MORE WAYS TO GIVE BACK. -

Title Composer Lyricist Arranger Cover Artist Publisher Date Notes Sabbath Chimes (Reverie) F

Title Composer Lyricist Arranger Cover artist Publisher Date Notes Sabbath Chimes (Reverie) F. Henri Klickmann Harold Rossiter Music Co. 1913 Sack Waltz, The John A. Metcalf Starmer Eclipse Pub. Co. [1924] Sadie O'Brady Billy Lindemann Billy Lindemann Broadway Music Corp. 1924 Sadie, The Princess of Tenement Row Frederick V. Bowers Chas. Horwitz J.B. Eddy Jos. W. Stern & Co. 1903 Sail Along, Silv'ry Moon Percy Wenrich Harry Tobias Joy Music Inc 1942 Sail on to Ceylon Herman Paley Edward Madden Starmer Jerome R. Remick & Co. 1916 Sailin' Away on the Henry Clay Egbert Van Alstyne Gus Kahn Starmer Jerome H. Remick & Co. 1917 Sailin' Away on the Henry Clay Egbert Van Alstyne Gus Kahn Starmer Jerome H. Remick & Co. 1917 Sailing Down the Chesapeake Bay George Botsford Jean C. Havez Starmer Jerome H. Remick & Co. 1913 Sailing Home Walter G. Samuels Walter G. Samuels IM Merman Words and Music Inc. 1937 Saint Louis Blues W.C. Handy W.C. Handy NA Tivick Handy Bros. Music Co. Inc. 1914 Includes ukulele arrangement Saint Louis Blues W.C. Handy W.C. Handy Barbelle Handy Bros. Music Co. Inc. 1942 Sakes Alive (March and Two-Step) Stephen Howard G.L. Lansing M. Witmark & Sons 1903 Banjo solo Sally in our Alley Henry Carey Henry Carey Starmer Armstronf Music Publishing Co. 1902 Sally Lou Hugo Frey Hugo Frey Robbins-Engel Inc. 1924 De Sylva Brown and Henderson Sally of My Dreams William Kernell William Kernell Joseph M. Weiss Inc. 1928 Sally Won't You Come Back? Dave Stamper Gene Buck Harms Inc. -

Ms Coll\Wheeler, R. Wheeler, Roger, Collector. Theatrical

Ms Coll\Wheeler, R. Wheeler, Roger, collector. Theatrical memorabilia, 1770-1940. 15 linear ft. (ca. 12,800 items in 32 boxes). Biography: Proprietor of Rare Old Programs, Newtonville, Mass. Summary: Theatrical memorabilia such as programs, playbills, photographs, engravings, and prints. Although there are some playbills as early as 1770, most of the material is from the 19th and 20th centuries. In addition to plays there is some material relating to concerts, operettas, musical comedies, musical revues, and movies. The majority of the collection centers around Shakespeare. Included with an unbound copy of each play (The Edinburgh Shakespeare Folio Edition) there are portraits, engravings, and photographs of actors in their roles; playbills; programs; cast lists; other types of illustrative material; reviews of various productions; and other printed material. Such well known names as George Arliss, Sarah Bernhardt, the Booths, John Drew, the Barrymores, and William Gillette are included in this collection. Organization: Arranged. Finding aids: Contents list, 19p. Restrictions on use: Collection is shelved offsite and requires 48 hours for access. Available for faculty, students, and researchers engaged in scholarly or publication projects. Permission to publish materials must be obtained in writing from the Librarian for Rare Books and Manuscripts. 1. Arliss, George, 1868-1946. 2. Bernhardt, Sarah, 1844-1923. 3. Booth, Edwin, 1833-1893. 4. Booth, John Wilkes, 1838-1865. 5. Booth, Junius Brutus, 1796-1852. 6. Drew, John, 1827-1862. 7. Drew, John, 1853-1927. 8. Barrymore, Lionel, 1878-1954. 9. Barrymore, Ethel, 1879-1959. 10. Barrymore, Georgiana Drew, 1856- 1893. 11. Barrymore, John, 1882-1942. 12. Barrymore, Maurice, 1848-1904. -

“To Be an American”: How Irving Berlin Assimilated Jewishness and Blackness in His Early Songs

“To Be an American”: How Irving Berlin Assimilated Jewishness and Blackness in his Early Songs A document submitted to The Graduate School of the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS in the Performance Studies Division of the College-Conservatory of Music 2011 by Kimberly Gelbwasser B.M., Northwestern University, 2004 M.M., University of Cincinnati, 2006 Committee Chair: Steven Cahn, Ph.D. Abstract During the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, millions of immigrants from Central and Eastern Europe as well as the Mediterranean countries arrived in the United States. New York City, in particular, became a hub where various nationalities coexisted and intermingled. Adding to the immigrant population were massive waves of former slaves migrating from the South. In this radically multicultural environment, Irving Berlin, a Jewish- Russian immigrant, became a songwriter. The cultural interaction that had the most profound effect upon Berlin’s early songwriting from 1907 to 1914 was that between his own Jewish population and the African-American population in New York City. In his early songs, Berlin highlights both Jewish and African- American stereotypical identities. Examining stereotypical ethnic markers in Berlin’s early songs reveals how he first revised and then traded his old Jewish identity for a new American identity as the “King of Ragtime.” This document presents two case studies that explore how Berlin not only incorporated stereotypical musical and textual markers of “blackness” within two of his individual Jewish novelty songs, but also converted them later to genres termed “coon” and “ragtime,” which were associated with African Americans.