DINOSAUR BOOKLET No. 1 Neovenator Salerii

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dinosaurs British Isles

DINOSAURS of the BRITISH ISLES Dean R. Lomax & Nobumichi Tamura Foreword by Dr Paul M. Barrett (Natural History Museum, London) Skeletal reconstructions by Scott Hartman, Jaime A. Headden & Gregory S. Paul Life and scene reconstructions by Nobumichi Tamura & James McKay CONTENTS Foreword by Dr Paul M. Barrett.............................................................................10 Foreword by the authors........................................................................................11 Acknowledgements................................................................................................12 Museum and institutional abbreviations...............................................................13 Introduction: An age-old interest..........................................................................16 What is a dinosaur?................................................................................................18 The question of birds and the ‘extinction’ of the dinosaurs..................................25 The age of dinosaurs..............................................................................................30 Taxonomy: The naming of species.......................................................................34 Dinosaur classification...........................................................................................37 Saurischian dinosaurs............................................................................................39 Theropoda............................................................................................................39 -

Theropoda: Spinosauridae) from the Middle Cretaceous of Morocco and Implications for Spinosaur Ecology

Cretaceous Research 93 (2019) 129e142 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Cretaceous Research journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/CretRes Juvenile spinosaurs (Theropoda: Spinosauridae) from the middle Cretaceous of Morocco and implications for spinosaur ecology * Rebecca J. Lakin , Nicholas R. Longrich Department of Biology and Biochemistry, Milner Centre for Evolution, University of Bath, Bath, BA2 7AY, UK article info abstract Article history: The Spinosauridae is a specialised clade of theropod dinosaurs known from the Berriasian to the Cen- Received 29 May 2018 omanian of Africa, South America, Europe and Asia. Spinosaurs were unusual among non-avian di- Received in revised form nosaurs in exploiting a piscivorous niche within riverine and estuarine habitats, and they include the 24 August 2018 largest known theropod. Although fossils of giant spinosaurs are increasingly well-represented in the Accepted in revised form 18 September fossil record, little juvenile material has been described. Here, we describe new examples of juvenile 2018 Available online 19 September 2018 spinosaurines from the middle Cretaceous (Cenomanian) Kem Kem beds of Morocco. The fossils include material from a range of sizes and are relatively common within the Kem Kem deposits, suggesting that Keywords: juveniles exploited the same semiaquatic niche as the adults throughout ontogeny. This implies that the Dinosauria Cenomanian delta habitats supported an age-inclusive population of spinosaurs that was neither Spinosauridae geographically or environmentally separated, though some ecological separation between juveniles and Juvenile adults is likely based on the large variation in size. Bones or teeth of very small (<2 m) spinosaurs have Ontogeny not been found, however. This could represent a taphonomic bias, or potentially an ecological signal that Cretaceous the earliest ontogenetic stages inhabited distinct environments. -

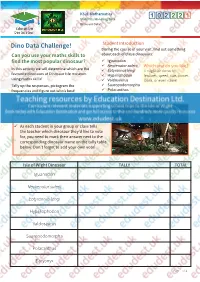

Dino Data Challenge!

KS2L Mathematics 102221 Statistics/Handling Data Dinosaur Data! Student Introduction Dino Data Challenge! During the course of your visit, find out something Can you use your maths skills to about each of these dinosaurs: find the most popular dinosaur? ü Iguanodon ü Neovenator salerii Which one do you like? In this activity we will determine which are the ü Eotyrannus lengi It might be down to favourite dinosaurs at Dinosaur Isle museum ü Hypsiliphodon features, speed, size, power, using maths skills! ü Valdosaurus looks, or even name! Tally up the responses, pictogram the ü Sauropodomorpha frequencies and figure out who’s best! ü Polacanthus ü Baryonyx Charting your favourite dinosaurs! Task 1 - Tally ü As each student in your group or class tells the teacher which dinosaur they’d like to vote for, you need to mark their answer next to the corresponding dinosaur name on the tally table below. Don’t forget to add your own vote! Isle of Wight Dinosaur TALLY TOTAL Iguanodon Neovenator salerii Eotyrannus lengi Hypsilophodon Valdosaurus Sauropodomorpha Polacanthus Baryonyx Page 1 of 4 Task 2 - Pictogram The frequency of each vote on the tally chart now needs to be shown on the pictogram below. Draw one dinosaur in the correct column for each vote received. Iguanodon Neovenator Eotyrannus Hypsilipho- Valdosaurus Sauropodo- Polacanthus Baryonyx don morpha 102221 Page 2 of 4 OPTIONAL: Cut out and stick dinosaurs! Iguanodon Neovenator Eotyrannus Hypsiliphodon 102221 OPTIONAL: Cut out and stick dinosaurs! Valdosaurus Sauropodomorpha Polacanthus Baryonyx ©2014 Education Destination www.educationdestination.co.uk 102221 Images © Dinosaur Isle. -

Geotourism and Geoconservation on the Isle of Wight, UK: Balancing Science with Commerce

Carpenter: Rocky start of Dinosaur National Monument… Geoconservation Research Original Article Geotourism and Geoconservation on the Isle of Wight, UK: Balancing Science with Commerce Martin I. Simpson Lansdowne, Military Rd, Chale, Isle of Wight, PO38 2HH, UK. Abstract The Isle of Wight has a rich and varied geological heritage which attracts scientists, tourists and fossil collectors, both private and commercial. Each party has a role to play in geoconservation and geotourism, but a policy on the long term curation of scientifically important specimens is essential to prevent future conflicts. A new code of conduct is recommended, based on the one adopted on the Jurassic Coast of Dorset. I have spent over 40 years living on the Island and working in the tourist industry running geology field-trips for both academics and tourists, and managing one of the longest running geological gift shops. I see the geological heritage and fossil sites as valuable geotourism assets, and envisage no problems with respect to the scientifically important material provided that a clear collecting policy is adopted, and the local museum generates funding to ensure that significant finds remain on the Island. A positive attitude is recommended in view of past experiences. Corresponding Author: Martin I. Simpson Lansdowne, Military Rd, Chale, Isle of Wight, PO38 2HH, UK. Email: [email protected] Keywords: Palaeontology, Geology, Isle of Wight, Tourism. Introduction with few formations absent, probably one of the best successions of this type in Europe (Fig 1c).Once a larger landmass joined to the mainland The Isle of Wight is a small, vaguely lozenge-shaped island situated as recently as 9000 years ago, what remains as 'Wight Island' or 'Vecta just off the central south coast of England, about 113 km south west of Insula' is eroding away at a rate of one metre per year in places (Munt London (Fig 1a, 1b), renowned for its balmy climate and golden, sandy 2016), but this erosion has produced spectacular scenery and iconic beaches. -

DINOSAUR BOOKLET No. 2 Iguanodon Bernissartensis and Mantellisaurus Atherfieldensis

DINOSAUR BOOKLET No. 2 Iguanodon bernissartensis and Mantellisaurus atherfieldensis Description Iguanodon (pronounced 'Ig-wan-oh-don') was one of the first dinosaurs to be named. The name is derived from 'Iguana' - a type of modern reptile, and 'don' meaning tooth. Iguanodon is the name of a small group of dinosaurs within the much larger group called Iguanodontids; they were large herbivores, with a long tail for balance, and hind legs that were longer than their fore limbs. There were three large hooved toes on each foot, and four fingers and a thumb spike on each hand. The mouth had a battery of chewing teeth, and a boney beak in place of front teeth. Since its initial discovery in the early nineteenth century, and more detailed reconstructions after complete skeletons were found in a Belgian mine in 1878, we have been forced to re-evaluate its posture, shape and movement; and to look again at how it fits in with other members of the Iguanodontids. Fossil remains from the group show they existed from the late Jurassic through to the late Cretaceous. Here on the Isle of Wight it was once thought there were two basic species of Iguanodon; a larger form called Iguanodon bernissartensis, and a more graceful species called Iguanodon atherfieldensis. The first was named after the Belgian town where complete skeletons were found (Bernissart) and the latter from Atherfield on the south west coast of the Isle of Wight. However 1 more recently palaeontologist Gregory Paul has moved our smaller variety to a new genera, leaving us with only one Iguanodon but a new genera of Iguanodontid called Mantellisaurus atherfieldensis (named after Gideon Mantell) in its place. -

Our Museum Dinosaurs

Our Museum Dinosaurs Coelophysis Tyrannosaurus Means: ‘hollow form’ Means: ‘tyrant lizard’ Say it: seel-oh-FIE-sis Say it: tie-ran-oh-SORE-us Where found: USA Where found: USA, Canada Type: Theropod Type: Theropod Length: 3m Length: 12m Height: 2m Height: 3.6m Weight: 27kg Weight: 8,300kg How it moved: walked on two legs, may have run How it moved: swiftly on two legs Teeth: 60 saw-edged, bone-crushing, pointed Teeth: small and sharp teeth in immensely strong jaws Type of feeder: CARNIVORE Type of feeder: CARNIVORE + SCAVENGER Food: small reptiles and insects Food: all other animals When it lived: 225-220 million years ago When it lived: 68-66 million years ago In the museum In the museum Models of Coelophysis Full size replica of its skull REAL fossil footprints Polacanthus Edmontosaurus Means: ‘many prickles’ Means: ‘Edmonton lizard’ Say it: pole-a-CAN-thus Say it: ed-mon-toe-SORE-us Where found: England Where found: North America Type: Ankylosaur Type: Hadrosaur Length: 5m Length: 13m Height: 1m Height: 3.5m Weight: 2 tonnes Weight: 3,400kg How it moved: walked on four legs How it moved: on two or four legs Teeth: small Teeth: horny beak, 200 grinding cheek teeth Type of feeder: HERBIVORE Type of feeder: HERBIVORE Food: plants Food: pine needles, seeds, twigs and leaves When it lived: 130-125 million years ago When it lived: 73-66 million years ago In the museum In the museum Partial skeleton of A REAL Edmontosaurus skeleton Polacanthus (in rock) Fossil Edmontosaurus skin imprint Hypsilophodon Dracoraptor Means: ‘high-crested tooth’ Means: ‘dragon robber’ Say it: hip-sih-LOW-foh-don Say it: DRAY-co-RAP-tor Where found: Isle of Wight, England Where found: Wales Type: Ornithiscian (orn-i-thi-SHE-an) Type: Theropod Length: around 3m Length: 1.8m Height: around 1m Height: 0.8m (80cm) Weight: around 25kg Weight: 20kg How it moved: walked or ran on two legs How it moved: swiftly on two legs Teeth: small pointed serrated teeth Teeth: horny beak, c. -

Cranial Anatomy of Allosaurus Jimmadseni, a New Species from the Lower Part of the Morrison Formation (Upper Jurassic) of Western North America

Cranial anatomy of Allosaurus jimmadseni, a new species from the lower part of the Morrison Formation (Upper Jurassic) of Western North America Daniel J. Chure1,2,* and Mark A. Loewen3,4,* 1 Dinosaur National Monument (retired), Jensen, UT, USA 2 Independent Researcher, Jensen, UT, USA 3 Natural History Museum of Utah, University of Utah, Salt Lake City, UT, USA 4 Department of Geology and Geophysics, University of Utah, Salt Lake City, UT, USA * These authors contributed equally to this work. ABSTRACT Allosaurus is one of the best known theropod dinosaurs from the Jurassic and a crucial taxon in phylogenetic analyses. On the basis of an in-depth, firsthand study of the bulk of Allosaurus specimens housed in North American institutions, we describe here a new theropod dinosaur from the Upper Jurassic Morrison Formation of Western North America, Allosaurus jimmadseni sp. nov., based upon a remarkably complete articulated skeleton and skull and a second specimen with an articulated skull and associated skeleton. The present study also assigns several other specimens to this new species, Allosaurus jimmadseni, which is characterized by a number of autapomorphies present on the dermal skull roof and additional characters present in the postcrania. In particular, whereas the ventral margin of the jugal of Allosaurus fragilis has pronounced sigmoidal convexity, the ventral margin is virtually straight in Allosaurus jimmadseni. The paired nasals of Allosaurus jimmadseni possess bilateral, blade-like crests along the lateral margin, forming a pronounced nasolacrimal crest that is absent in Allosaurus fragilis. Submitted 20 July 2018 Accepted 31 August 2019 Subjects Paleontology, Taxonomy Published 24 January 2020 Keywords Allosaurus, Allosaurus jimmadseni, Dinosaur, Theropod, Morrison Formation, Jurassic, Corresponding author Cranial anatomy Mark A. -

A Century of Spinosaurs - a Review and Revision of the Spinosauridae

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Queen Mary Research Online A century of spinosaurs - a review and revision of the Spinosauridae with comments on their ecology HONE David William Elliott1, * HOLTZ Thomas Richard Jnr2 1 School of Biological and Chemical Sciences, Queen Mary University of London, London, E1 4NS, UK 2 Department of Geology, University of Maryland, College Park, MD 20742 USA Abstract: The spinosaurids represent an enigmatic and highly unusual form of large tetanuran theropods that were first identified in 1915. A recent flurry of discoveries and taxonomic revisions of this important and interesting clade had added greatly to our knowledge, however, spinosaur body fossils are generally rare and most species are known from only limited skeletal remains. Their unusual anatomical adaptations to the skull, limbs and axial column all differ from other large theropods and point to an unusual ecological niche and a lifestyle intimately linked to water. Keywords: Theropoda, Megalosauroidea, Baryonychinae, Spinosaurinae, palaeoecology E-mail: [email protected] 1 Introduction The Spinosauridae is an enigmatic clade of large and carnivorous theropods from the Jurassic and Cretaceous that are known from both Gondwana and Laurasia (Holtz et al., 2004). Despite their wide temporal and geographic distribution, the clade is known primarily from teeth and the body fossil record is extremely limited (Bertin, 2010). As such, relatively little is known about this group of animals, although their unusual morphology with regard to skull shape, dentition, dorsal neural spines and other features mark them out as divergent from the essential bauplan of other non-tetanuran theropods (Fig 1). -

A New Clade of Archaic Large-Bodied Predatory Dinosaurs (Theropoda: Allosauroidea) That Survived to the Latest Mesozoic

Naturwissenschaften (2010) 97:71–78 DOI 10.1007/s00114-009-0614-x ORIGINAL PAPER A new clade of archaic large-bodied predatory dinosaurs (Theropoda: Allosauroidea) that survived to the latest Mesozoic Roger B. J. Benson & Matthew T. Carrano & Stephen L. Brusatte Received: 26 August 2009 /Revised: 27 September 2009 /Accepted: 29 September 2009 /Published online: 14 October 2009 # Springer-Verlag 2009 Abstract Non-avian theropod dinosaurs attained large Neovenatoridae includes a derived group (Megaraptora, body sizes, monopolising terrestrial apex predator niches new clade) that developed long, raptorial forelimbs, in the Jurassic–Cretaceous. From the Middle Jurassic cursorial hind limbs, appendicular pneumaticity and small onwards, Allosauroidea and Megalosauroidea comprised size, features acquired convergently in bird-line theropods. almost all large-bodied predators for 85 million years. Neovenatorids thus occupied a 14-fold adult size range Despite their enormous success, however, they are usually from 175 kg (Fukuiraptor) to approximately 2,500 kg considered absent from terminal Cretaceous ecosystems, (Chilantaisaurus). Recognition of this major allosauroid replaced by tyrannosaurids and abelisaurids. We demon- radiation has implications for Gondwanan paleobiogeog- strate that the problematic allosauroids Aerosteon, Austral- raphy: The distribution of early Cretaceous allosauroids ovenator, Fukuiraptor and Neovenator form a previously does not strongly support the vicariant hypothesis of unrecognised but ecologically diverse and globally distrib- southern dinosaur evolution or any particular continental uted clade (Neovenatoridae, new clade) with the hitherto breakup sequence or dispersal scenario. Instead, clades enigmatic theropods Chilantaisaurus, Megaraptor and the were nearly cosmopolitan in their early history, and later Maastrichtian Orkoraptor. This refutes the notion that distributions are explained by sampling failure or local allosauroid extinction pre-dated the end of the Mesozoic. -

Abstracts (Pdf)

63RD SYMPOSIUM FOR VERTEBRATE PALAEONTOLOGY AND COMPARATIVE ANATOMY & 24TH SYMPOSIUM OF PALAEONTOLOGICAL PREPARATION AND CONSERVATION WITH THE GEOLOGICAL CURATORS’ GROUP 1 CONTENTS Meeting Schedule 4 Abstracts SPPC talks 10 SVPCA talks 14 SVPCA posters 78 Delegate List 112 2 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The organisers would like to thank the Palaeontological Association for their support of this meeting, and also for their continued management of the Jones Fenleigh Memorial Fund. A huge amount of the work putting the meeting together was co-ordinated by Mark Young, including editing this Abstract volume, handling abstract submissions and overall organisation. We also thank Stu Pond and Jessica Lawrence Wujek for designing this year's SVPCA logo. Liz Martin-Silverstone and Jessica Lawrence Wujek co-ordinated most of the behind-the- scenes management for this meeting while Stu Pond designed this year’s Conference circulars. Our logo represents a local fossil, Polacanthus from the Isle of Wight (based on a fossil collected by Martin Simpson and Lyn Spearpoint). Finally, we thank Richard Forrest for working on the website and providing general information and support. This year’s meetings are supported by the Hampshire Cultural Trust, Dinosaur Isle, Geological Curators Group, Siri Scientific Press, Palaeocast and Frontiers in Earth Science. HOST COMMITTEE Ocean and Earth Science, University of Southampton, National Oceanography Centre Gareth Dyke John Marshall Darren Naish Mark Young Jessica Lawrence Wujek Liz Martin-Silverstone Stu Pond Aubrey Roberts James Hansford Hampshire Cultural Trust Christine Taylor Dinosaur Isle Gary Blackwell Geological Curator's Group Kathryn Riddington 3 MEETING SCHEDULE Monday 31st August 9:00-9:45 SPPC/GCG registration at NOC Security desk (4th floor) Session — SPPC Chair — Mark Young 10:00-10:20 Mark Graham Fossils, Footprints & Fakes 10:20-10:40 Emma Bernard A brief history of the best collection of fossil fish in the world – probably… 10:40-11:00 Jeff Liston et al. -

Newsletter Number 52

The Palaeontology Newsletter Contents 52 Association Business 2 AGM 14 News 16 Association Meetings 20 From our own correspondents Conceptual fossils 24 Sutures joining Ontogeny and Fossils 29 Correspondence 33 Big Gamble for a Big Dead Fish 40 The Mystery Fossil 43 Obituary: Frank Hodson 46 Future meetings of other bodies 48 Meeting Reports 56 Book Reviews 68 Palaeontology vol 46 parts 1, 2, 3 99–101 Special Papers in Palaeontology no. 68 102 Reminder: The deadline for copy for Issue no 53 is 27th June 2003 On the Web: http://www.palass.org/ Newsletter 52 2 Newsletter 52 3 Meetings. Four meetings were held in 2002, and the Association extends its thanks to the Association Business organisers and host institutions of these meetings. a. Lyell Meeting. “Approaches to Reconstructing Phylogeny”, was convened on behalf of the Annual Report for 2002 Association by Prof. Gale (University of Greenwich) and Dr P.C.J. Donoghue (Lapworth Museum, University of Birmingham). Nature of the Association. The Palaeontological Association is a Charity registered in England, b. Forty-fifth Annual General Meeting and Address. 8th May. The address, entitled “Life and Charity Number 276369. Its Governing Instrument is the Constitution adopted on 27 February work of S.S. Buckmann (1860-1929) Geobiochronologist and the problems of assessing the work of 1957, amended on subsequent occasions as recorded in the Council Minutes. Trustees (Council past palaeontologists,” was given by Prof. Hugh Torrens and attended by 40 people. The meeting Members) are elected by vote of the Membership at the Annual General Meeting. The contact was held at the University of Birmingham and organised by Dr M.P. -

Appendix S1–Neovenatoridae Benson, Carrano, Brusatte 2009

Appendix S1–Neovenatoridae Benson, Carrano, Brusatte 2009 A new clade of archaic large-bodied predatory dinosaurs (Theropoda: Allosauroidea) that survived to the latest Mesozoic Benson RBJ, Carrano MT & Brusatte SL. Appendix S1 (a) Institutional abbreviations. AODF, Australian Age of Dinosaurs, Queensland, Australia; BMNH, Natural History Museum, London, UK; BYU, Brigham Young University Museum of Geology, Provo, Utah, USA; FPDM, Fukui Prefectural Dinosaur Museum, Fukui, Japan; IVPP, Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology, Beijing, China; MCNA, Museo de Ciencas Naturales y Anthropológicas (J.C. Moyano) de Mendoza, Mendoza, Argentina; MCF, Museo Carmen Funes, Plaza Huincul, Argentina; MIWG, ‘Dinosaur Isle’ Museum of Isle of Wight Geology, Sandown, UK; MNN, Musée National du Niger, Niamey, Niger; MPM Museo Padre Molina, Río Gallegos, Santa Cruz, Argentina; MUCP, Museo de Geología y Paleontología, Universidad Nacional del Comahue, Neuquén, Argentina; NCSM, North Carolina State Museum, Rayleigh, USA; NMV, Museum of Victoria, Melbourne, Australia; OMNH, Sam Noble Oklahoma Museum of Natural History, Norman, Oklahoma, USA; UMNH, Utah Museum of Natural History, Salt Lake City, Utah, USA; ZPAL, Institute of Palaeobiology, Polish Academy of Sciences, Warsaw, Poland. (b) Comparisons. We directly examined all specimens of Chilantaisaurus, Megaraptor and Neovenator , and inspected high-quality casts and original bones of Aerosteon and published images of Australovenator (Hocknull et al. 2009), Fukuiraptor (Azuma & Currie 2000; Currie & Azuma 2006) and Orkoraptor (Novas et al. 2008). This formed part of an ongoing review of the taxonomy and systematics of basal theropods (MTC, RBJB & S.D. Sampson unpublished data; Carrano & Sampson 2004, 2008; Brusatte & Sereno 2008; Benson in press). A summary of the comparisons made here is presented in table S1.