Biological Flora of the British Isles: Ulmus Glabra

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Biology and Management of the Dutch Elm Disease Vector, Hylurgopinus Rufipes Eichhoff (Coleoptera: Curculionidae) in Manitoba By

Biology and Management of the Dutch Elm Disease Vector, Hylurgopinus rufipes Eichhoff (Coleoptera: Curculionidae) in Manitoba by Sunday Oghiakhe A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies of The University of Manitoba in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Entomology University of Manitoba Winnipeg Copyright © 2014 Sunday Oghiakhe Abstract Hylurgopinus rufipes, the native elm bark beetle (NEBB), is the major vector of Dutch elm disease (DED) in Manitoba. Dissections of American elms (Ulmus americana), in the same year as DED symptoms appeared in them, showed that NEBB constructed brood galleries in which a generation completed development, and adult NEBB carrying DED spores would probably leave the newly-symptomatic trees. Rapid removal of freshly diseased trees, completed by mid-August, will prevent spore-bearing NEBB emergence, and is recommended. The relationship between presence of NEBB in stained branch sections and the total number of NEEB per tree could be the basis for methods to prioritize trees for rapid removal. Numbers and densities of overwintering NEBB in elm trees decreased with increasing height, with >70% of the population overwintering above ground doing so in the basal 15 cm. Substantial numbers of NEBB overwinter below the soil surface, and could be unaffected by basal spraying. Mark-recapture studies showed that frequency of spore bearing by overwintering beetles averaged 45% for the wild population and 2% for marked NEBB released from disease-free logs. Most NEBB overwintered close to their emergence site, but some traveled ≥4.8 km before wintering. Studies comparing efficacy of insecticides showed that chlorpyrifos gave 100% control of overwintering NEBB for two years as did bifenthrin: however, permethrin and carbaryl provided transient efficacy. -

Elms Grown in America

ARNOLDIA A continuation of the BULLETIN OF POPULAR INFORMATION of the Arnold Arboretum, Harvard University VOLUME I DECEMBER I 9, 19411 NUMBER IS ELMS GROVG’N IN AMERICA years ago, Professor Charles S. Sargent, Director T~’ENTY-FIVEof the Arnold Arburetum w rote the following statement concerning the European Elms-unfortunately just as true today as it was then - "There is probably more confusion in the identification and proper naming of these trees (the European elms) in American parl.s and gar- dens than of any other group of trees, and it is only in very recent ~ ears that English botanists have been able to reach what appear to be sound conclusions in regard to them. The confusion started with Lin- naeus, who believed that all European elms belonged to one species, and it has been increased by the appearance of natural hybrids of at least two of the species and by the tendency of seedlings to show much variation from the original types." Today, with six elm species native in the United State, five species native of Europe (including many varieties), and se‘ eral more species native of Asia, the picture becomes even more confused. The elm is, and always has been, a standard shade tree, for even though it is threatened in certain sections by the Dutch elm disease, the gardening public will still plant elms. Approximately fifty elms will be mentioned in this bulletin. About thirty of them have been listed as available in - the nurseries of this country during the past two years : all but five of them are growing in the Arnold Arboretum at Boston. -

Faune De Belgique: Insectes Coléoptères Lamellicornes

Bulletin de la Société royale belge d’Entomologie/Bulletin van de Koninklijke Belgische Vereniging voor Entomologie, 151 (2015): 107-114 Can Flower chafers be monitored for conservation purpose with odour traps? (Coleoptera: Cetoniidae) Arno THOMAES Research Institute for Nature and Forest (INBO), Kliniekstraat 25, B-1070 Brussels (email: [email protected]) Abstract Monitoring is becoming an increasingly important for nature conservation. We tested odour traps for the monitoring of Flower chafers (Cetoniidae). These traps have been designed for eradication or monitoring the beetles in Mediterranean orchards where these beetles can be present in large numbers. Therefore, it is unclear whether these traps can be used to monitor these species in Northern Europe at sites where these species have relatively low population sizes. Odour traps for Cetonia aurata Linnaeus, 1761 and Protaetia cuprea Fabricius, 1775 were tested in five sites in Belgium and odour traps for Oxythyrea funesta Poda, 1761 and Tropinota hirta (Poda, 1761) at one site. In total 5 C. aurata , 17 Protaetia metallica (Herbst, 1782) and 2 O. funesta were captured. Furthermore, some more common Cetoniidae were found besides 909 non-Cetoniidae invertebrates. I conclude that the traps are not interesting to monitor C. aurata when the species is relatively rare. However, the traps seem to be useful to monitor P. metallica and to detect O. funesta even if it is present in low numbers. However, it is important to lower the high mortality rate of predominantly honeybee and bumblebees by adapting the trap design. Keywords: Cetoniidae, monitoring, odour traps, Cetonia aurata, Protaetia metallica, Oxythyrea funesta. Samenvatting Monitoring wordt in toenemende mate belangrijk binnen het natuurbehoud. -

Dutch Elm Disease Pathogen Transmission by the Banded Elm Bark Beetle Scolytus Schevyrewi

For. Path. 43 (2013) 232–237 doi: 10.1111/efp.12023 © 2013 Blackwell Verlag GmbH Dutch elm disease pathogen transmission by the banded elm bark beetle Scolytus schevyrewi By W. R. Jacobi1,3, R. D. Koski1 and J. F. Negron2 1Department of Bioagricultural Sciences and Pest Management, Colorado State University, Fort Collins, CO 80523, USA; 2U.S.D.A. Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Forest Research Station, Fort Collins, CO USA; 3E-mail: [email protected] (for correspondence) Summary Dutch Elm Disease (DED) is a vascular wilt disease of Ulmus species (elms) incited in North America primarily by the exotic fungus Ophios- toma novo-ulmi. The pathogen is transmitted via root grafts and elm bark beetle vectors, including the native North American elm bark beetle, Hylurgopinus rufipes and the exotic smaller European elm bark beetle, Scolytus multistriatus. The banded elm bark beetle, Scolytus schevyrewi, is an exotic Asian bark beetle that is now apparently the dominant elm bark beetle in the Rocky Mountain region of the USA. It is not known if S. schevyrewi will have an equivalent vector competence or if management recommendations need to be updated. Thus the study objectives were to: (i) determine the type and size of wounds made by adult S. schevyrewi on branches of Ulmus americana and (ii) determine if adult S. schevyrewi can transfer the pathogen to American elms during maturation feeding. To determine the DED vectoring capability of S. schevyrewi, newly emerged adults were infested with spores of Ophiostoma novo-ulmi and then placed with either in-vivo or in-vitro branches of American elm trees. -

BAP Fungi Handbook English Nature Research Reports

Report Number 600 BAP fungi handbook English Nature Research Reports working today for nature tomorrow English Nature Research Reports Number 600 BAP fungi handbook Dr A. Martyn Ainsworth 53 Elm Road, Windsor, Berkshire. SL4 3NB October 2004 You may reproduce as many additional copies of this report as you like, provided such copies stipulate that copyright remains with English Nature, Northminster House, Peterborough PE1 1UA ISSN 0967-876X © Copyright English Nature 2004 Executive summary Fungi constitute one of the largest priority areas of biodiversity for which specialist knowledge, skills and research are most needed to secure effective conservation management. By drawing together what is known about the 27 priority BAP species selected prior to the 2005 BAP review and exploring some of the biological options open to fungi, this handbook aims to provide a compendium of ecological, taxonomic and conservation information specifically with conservationists’ needs in mind. The opening section on fungus fundamentals is an illustrated account of the relative importance of mycelia, fruit bodies and spores, without which many ecosystem nutrient cycles would cease. It is not generally appreciated that mycelia have been recorded patrolling territories of hundreds of hectares, living over a thousand years or weighing as much as a blue whale. Inconspicuous fungi are therefore amongst the largest, heaviest and oldest living things on Earth. The following sections describe the various formal and informal taxonomic and ecological groupings, emphasizing the often intimate and mutually beneficial partnerships formed between fungi and other organisms. The different foraging strategies by which fungi explore their environment are also included, together with a summary of the consequences of encounters between fungi ranging from rejection, combat, merger, takeover and restructuring to nuclear exchanges and mating. -

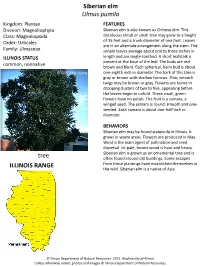

Siberian Elm Ulmus Pumila ILLINOIS RANGE Tree

Siberian elm Ulmus pumila Kingdom: Plantae FEATURES Division: Magnoliophyta Siberian elm is also known as Chinese elm. This Class: Magnoliopsida deciduous shrub or small tree may grow to a height Order: Urticales of 35 feet and a trunk diameter of one foot. Leaves are in an alternate arrangement along the stem. The Family: Ulmaceae simple leaves average about one to three inches in ILLINOIS STATUS length and are single-toothed. A short leafstalk is present at the base of the leaf. The buds are red- common, nonnative brown and blunt. Each spherical, hairy bud is about © Guy Sternberg one-eighth inch in diameter. The bark of this tree is gray or brown with shallow furrows. Thin, smooth twigs may be brown or gray. Flowers are borne in drooping clusters of two to five, appearing before the leaves begin to unfold. These small, green flowers have no petals. The fruit is a samara, a winged seed. The samara is round, smooth and one- seeded. Each samara is about one-half inch in diameter. BEHAVIORS Siberian elm may be found statewide in Illinois. It grows in waste areas. Flowers are produced in May. Wind is the main agent of pollination and seed dispersal. Its pale, brown wood is hard and heavy. Siberian elm is grown as an ornamental tree and is tree often found around old buildings. Some escapes from these plantings have established themselves in ILLINOIS RANGE the wild. Siberian elm is a native of Asia. © Illinois Department of Natural Resources. 2021. Biodiversity of Illinois. Unless otherwise noted, photos and images © Illinois Department of Natural Resources. -

Using Odour Traps for Population Monitoring and Dispersal Analysis of the Threatened Saproxylic Beetles Osmoderma Eremita and Elater Ferrugineus in Central Italy

J Insect Conserv (2014) 18:801–813 DOI 10.1007/s10841-014-9687-8 ORIGINAL PAPER Using odour traps for population monitoring and dispersal analysis of the threatened saproxylic beetles Osmoderma eremita and Elater ferrugineus in central Italy Agnese Zauli • Stefano Chiari • Erik Hedenstro¨m • Glenn P. Svensson • Giuseppe M. Carpaneto Received: 7 March 2014 / Accepted: 8 August 2014 / Published online: 17 August 2014 Ó Springer International Publishing Switzerland 2014 Abstract Pheromone-based monitoring could be a very lure compared to racemic c-decalactone in detecting its efficient method to assess the conservation status of rare presence. The population size at the two sites were esti- and elusive insect species, but there are still few studies for mated to 520 and 1,369 individuals, respectively. Our which pheromone traps have been used to obtain infor- model suggests a sampling effort of ten traps checked for mation on presence, abundance, phenology and movements 3 days being sufficient to detect the presence of E. ferru- of such insects. We performed a mark-recapture study of gineus at a given site. The distribution of dispersal dis- two threatened saproxylic beetles, Osmoderma eremita tances for the predator was best described by the negative (Scarabaeidae) and its predator Elater ferrugineus (Ela- exponential function with 1 % of the individuals dispersing teridae), in two beech forests of central Italy using phero- farther than 1,600 m from their natal site. In contrast to mone baited window traps and unbaited pitfall traps. Two studies on these beetles in Northern Europe, the activity lures were used: (1) the male-produced sex pheromone of pattern of the two beetle species was not influenced by O. -

Lacebark Elm Cultivars Ulmus Parvifolia

Lacebark Elm Cultivars Ulmus parvifolia P O Box 189 | Boring OR 97009 | 800-825-8202 | www.jfschmidt.com Ulmus parvifolia ‘Emer II’ PP 7552 Tall, upright and arching, this cultivar’s growth habit is unique Allee® Elm among U. parvifolia cultivars, Zone: 5 | Height: 50' | Spread: 35' being reminiscent of the grand Shape: Upright vase, arching American Elm. Its exfoliating Foliage: Medium green, glossy bark creates a mosaic of orange, Fall Color: Yellow-orange to rust red tan and gray, a beautiful sight on a mature tree. Discovered by DISEASE TOLERANCE: Dr. Michael Dirr of University of Dutch Elm Disease and phloem Georgia, Athens. necrosis Ulmus parvifolia ‘Emer I’ Bark of a mature tree is a mosaic of orange, tan, and gray patches, Athena® Classic Elm giving it as much interest in winter Zone: 5 | Height: 30' | Spread: 35' as in summer. The canopy is tightly Shape: Broadly rounded formed. Discovered by Dr. Michael Foliage: Medium green, glossy Dirr of University of Georgia, Fall Color: Yellowish Athens. DISEASE TOLERANCE: Dutch Elm Disease and phloem necrosis Ulmus parvifolia ‘UPMTF’ PP 11295 Bosque® is well shaped for plant- ing on city streets and in restricted Bosque® Elm spaces, thanks to its upright Zone: 6 | Height: 45' | Spread: 30' growth habit and narrow crown. Shape: Upright pyramidal to Fine textured and glossy, its dark broadly oval green foliage is complemented by Foliage: Dark green, glossy multi-colored exfoliating bark. Fall Color: Yellow-orange DISEASE TOLERANCE: Dutch Elm Disease and phloem necrosis Ulmus parvifolia ‘Dynasty’ A broadly rounded tree with fine textured foliage and good Dynasty Elm environ mental tolerance. -

Dutch Elm Disease (DED)

Revival of the American elm tree Ottawa, Ontario (March 29, 2012) – A healthy century old American elm on the campus of the University of Guelph could hold the key to reviving the species that has been decimated by Dutch elm disease (DED). This tree is an example of a small population of mature trees that have resisted the ravages of DED. A study published in the Canadian Journal of Forest Research (CJFR) examines using shoot buds from the tree to develop an in vitro conservation system for American elm trees. “Elm trees naturally live to be several hundred years old. As such, many of the mature elm trees that remain were present prior to the first DED epidemic,” says Praveen Saxena, one of the authors of the study. “The trees that have survived initial and subsequent epidemics potentially represent an invaluable source of disease resistance for future plantings and breeding programs.” Shoot tips and dormant buds were collected from a mature tree that was planted on the University of Guelph campus between 1903 and 1915. These tips and buds were used as the starting material to produce genetic clones of the parent trees. The culture system described in the study has been used successfully to establish a repository representing 17 mature American elms from Ontario. This will facilitate future conservation efforts for the American elm and may provide a framework for conservation of other endangered woody plant species. The American elm was once a mainstay in the urban landscape before DED began to kill the trees. Since its introduction to North America in 1930, Canada in 1945, DED has devastated the American elm population, killing 80%–95% of the trees. -

Molecular Identification of Fungi

Molecular Identification of Fungi Youssuf Gherbawy l Kerstin Voigt Editors Molecular Identification of Fungi Editors Prof. Dr. Youssuf Gherbawy Dr. Kerstin Voigt South Valley University University of Jena Faculty of Science School of Biology and Pharmacy Department of Botany Institute of Microbiology 83523 Qena, Egypt Neugasse 25 [email protected] 07743 Jena, Germany [email protected] ISBN 978-3-642-05041-1 e-ISBN 978-3-642-05042-8 DOI 10.1007/978-3-642-05042-8 Springer Heidelberg Dordrecht London New York Library of Congress Control Number: 2009938949 # Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg 2010 This work is subject to copyright. All rights are reserved, whether the whole or part of the material is concerned, specifically the rights of translation, reprinting, reuse of illustrations, recitation, broadcasting, reproduction on microfilm or in any other way, and storage in data banks. Duplication of this publication or parts thereof is permitted only under the provisions of the German Copyright Law of September 9, 1965, in its current version, and permission for use must always be obtained from Springer. Violations are liable to prosecution under the German Copyright Law. The use of general descriptive names, registered names, trademarks, etc. in this publication does not imply, even in the absence of a specific statement, that such names are exempt from the relevant protective laws and regulations and therefore free for general use. Cover design: WMXDesign GmbH, Heidelberg, Germany, kindly supported by ‘leopardy.com’ Printed on acid-free paper Springer is part of Springer Science+Business Media (www.springer.com) Dedicated to Prof. Lajos Ferenczy (1930–2004) microbiologist, mycologist and member of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences, one of the most outstanding Hungarian biologists of the twentieth century Preface Fungi comprise a vast variety of microorganisms and are numerically among the most abundant eukaryotes on Earth’s biosphere. -

Comparative Morphology of the Male Genitalia in Lepidoptera

COMPARATIVE MORPHOLOGY OF THE MALE GENITALIA IN LEPIDOPTERA. By DEV RAJ MEHTA, M. Sc.~ Ph. D. (Canta.b.), 'Univefsity Scholar of the Government of the Punjab, India (Department of Zoology, University of Oambridge). CONTENTS. PAGE. Introduction 197 Historical Review 199 Technique. 201 N ontenclature 201 Function • 205 Comparative Morphology 206 Conclusions in Phylogeny 257 Summary 261 Literature 1 262 INTRODUCTION. In the domains of both Morphology and Taxonomy the study' of Insect genitalia has evoked considerable interest during the past half century. Zander (1900, 1901, 1903) suggested a common structural plan for the genitalia in various orders of insects. This work stimulated further research and his conclusions were amplified by Crampton (1920) who homologized the different parts in the genitalia of Hymenoptera, Mecoptera, Neuroptera, Diptera, Trichoptera Lepidoptera, Hemiptera and Strepsiptera with those of more generalized insects like the Ephe meroptera and Thysanura. During this time the use of genitalic charac ters for taxonomic purposes was also realized particularly in cases where the other imaginal characters had failed to serve. In this con nection may be mentioned the work of Buchanan White (1876), Gosse (1883), Bethune Baker (1914), Pierce (1909, 1914, 1922) and others. Also, a comparative account of the genitalia, as a basis for the phylo genetic study of different insect orders, was employed by Walker (1919), Sharp and Muir (1912), Singh-Pruthi (1925) and Cole (1927), in Orthop tera, Coleoptera, Hemiptera and the Diptera respectively. It is sur prising, work of this nature having been found so useful in these groups, that an important order like the Lepidoptera should have escaped careful analysis at the hands of the morphologists. -

Open As a Single Document

ILLUSTRATIONS Professor Charles Sprague Sargent in the Arnold Arboretum Library -1904, Plate I, opposite p. 30 Flowers and fruits of the hardy orange, Porrcirus tr;f’oliata. Plate II, p. 35 Map showing absolute minimum temperatures in the Northeastern states from 1926-1940. Plate III, p. 47 Map showing an average length for growing season in the Northeast- ern states. Plate IV, p. 49 Map showing the average July temperature in the Northeastern states for the years 1926 to 1940. Plate V, p. 511 Black walnuts. Plate VI, p. 33 Hickory nuts of various types. Plate VII, p. 57 The native rock elm, Ulmu.r thomasi. Plate VIII, p. 69 The European white elm or Russian elm, Lllmus laenis. Plate IX, p.711 Two varieties of the smoothleaf elm, L’lmus carpinjfolia. Plate X, p. 755 Leaf specimens of various elm species. Plate XI, p. 79 111 . ARNOLDIA A continuation of the BULLETIN OF POPULAR INFORMATION of the Arnold Arboretum, Harvard University VOLUME 1 MARCH 14, 1941 NUMBER I A SIMPLE CHANGE IN NAME "Bulletin of Popular Information" has always been an un- OURsatisfactory periodical to cite, because of the form of its title, which reads: "Arnold Arboretum, Harvard University, Bulletin of Popular Information." Moreover, for no very obvious reason, in the twenty-nine years of its publication it has attamed four series, and for clarity it is necessary to cite the series as well as the volume. In- itiated in May, 1911, sixty-three unpaged numbers form the first series, this run closing in November, 1914. In 1915, a new series was commenced with volume one and was continued for twelve years, closing with volume twelve in December, 1926.