Sculpture of To-Day

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lorado Taft Midway Studios AND/OR COMMON Lorado Taft Midway Studios______I LOCATION

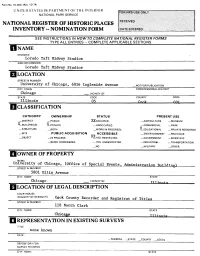

Form No. 10-300 (Rev. 10-74) UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES INVENTORY -- NOMINATION FORM SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOW TO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS ___________TYPE ALL ENTRIES - COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS______ | NAME HISTORIC Lorado Taft Midway Studios AND/OR COMMON Lorado Taft Midway Studios______________________________ I LOCATION STREET & NUMBER University of Chicago, 6016 Ingleside Avenue —NOT FOR PUBLICATION CITY. TOWN CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT Chicago __ VICINITY OF STATE CODE COUNTY CODE Illinois 05 P.onV CLASSIFICATION CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE _DISTRICT —PUBLIC XXOCCUPIED _ AGRICULTURE —MUSEUM X_BUILDING(S) ?_PRIVATE —UNOCCUPIED —COMMERCIAL —PARK —STRUCTURE —BOTH _ WORK IN PROGRESS ^-EDUCATIONAL —PRIVATE RESIDENCE _ SITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE —ENTERTAINMENT —RELIGIOUS —OBJECT —IN PROCESS —YES: RESTRICTED —GOVERNMENT —SCIENTIFIC —BEING CONSIDERED _ YES: UNRESTRICTED —INDUSTRIAL —TRANSPORTATION _NO —MILITARY —OTHER. (OWNER OF PROPERTY NAMEINAMt University of Chicago, (Office of Special Events, Administration STREET & NUMBER 5801 Ellis Avenue CITY. TOWN STATE VICINITY OF Chicago T1 1 inr>i' a LOCATION OF LEGAL DESCRIPTION COURTHOUSE, REGISTRY OF DEEps.ETc. Cook County Recorder and Registrat of Titles STREET & NUMBER 118 North Clark CITY. TOWN STATE Chicago Tllinm', REPRESENTATION IN EXISTING SURVEYS TITLE none known DATE — FEDERAL —STATE —COUNTY —LOCAL DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS CITY. TOWN STATE DESCRIPTION CONDITION CHECK ONE CHECK ONE YY —EXCELLENT _DETERIORATED —UNALTERED —ORIGINAL SITE XXQOOD —RUINS XXALTERED —MOVED DATE_______ —FAIR —UNEXPOSED DESCRIBETHE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL (IF KNOWN) PHYSICAL APPEARANCE Lorado Taft's wife, Ada Bartlett Taft y described the Midway Studios in her biography of her husband, Lorado Taft, Sculptor arid Citizen; In 1906 Lorado moved his main studio out of the crowded Loop into a large, deserted brick barn on the University of Chicago property on the Midway. -

The London List

The London List YEARBOOK 2010 FOREWORD 4 GAZETTEER 5 Commemorative Structures 6 Commercial Buildings 12 Cultural and Entertainment 18 Domestic 22 Education 32 Garden and Park 36 Health and Welfare 38 Industrial 44 Law and Government 46 Maritime and Naval 48 Military 50 Places of Worship 54 Street Furniture 62 Transport Buildings 65 Utilities and Communications 66 INDEX 68 TheListed London in London: List: yearbookyearbook 20102010 22 Contents Foreword ....................................................................................4 Gazetteer ...................................................................................5 Commemorative Structures .......................................................6 Commercial Buildings ..................................................................12 Cultural and Entertainment .....................................................18 Domestic ............................................................................................22 Education ............................................................................................32 Garden and Park ............................................................................36 Health and Welfare ......................................................................38 Industrial ..............................................................................................44 Law and Government .................................................................46 Maritime and Naval ......................................................................48 -

3.1901 Buffalo Endurance Run.2.Pdf

The Morrisania Court fined David W. Bishop Jr. $10 after he was arrested for exceeding the 15 miles per hour speed limit. This was the very reason that the endurance run committee created a maximum 15 miles per hour speed as most municipalities at that time posted 15 miles per hour speed limits, or less! Photo from the September 18, 1901 issue of Horseless Age magazine. Stage One was dusty with deep and bumpy sandy ruts once the contestants departed New York City. The route was difficult to follow. In one village the speed limit was 4 miles per hour. Some hills were difficult to climb and then the downhill run the cars “frequently exceeded 25 miles per hour!” At the closing of the Poughkeepsie control at 9:30 PM seventy-five of the eighty starters had arrived. For stage Two the weather was good but the roads “varying from good to bad and treacherous.” Sixty-five vehicles arrived in Albany within the time limit. Wednesday September 11 the automobiles had to “slacken their speed” due to wet roads in the morning and heavy rain in the afternoon. All the vehicles “skidded to the point of danger.” 51 vehicles reached Herkimer before 9:40, the time of closing the control. Stage Four on Thursday September 12th was another day of rain. The “roads were mostly miserable in the morning with only a few fair stretches.” Tire and axle failure at this point of the endurance run was high. 48 vehicles arrived at the Syracuse closing of the control at 9:30 PM. -

It Is Now a Number of Years Since the Bowman Sculpture Gallery Has Held

It is now a number of years since the Bowman Sculpture Gallery has held an exhibition solely focused on The New School of British Sculpture and it is a pleasure to see the Gallery again showing extensive examples of the leading artists involved. The New British School, also referred to as the New Sculpture, followed a period when the Neo Classicism of such sculptors as Canova, Thorvaldsen and Gibson was regarded as the acme of their art and they featured in many of the great Houses of the time. Towards the end of the 19th Century the expanding middle class, who had a growing interest in the Arts, created a demand for smaller and more domestic sculpture began. At the same time painters such as Lord Leighton, who sculpted Athlete Wrestling with a Python and The Sluggard, and George Frederick Watts, who produced the great monument Physical Energy, were bringing ‘colour’ into the subject by varied patination and their treatment of shape. This movement was undoubtedly fuelled by a reaction against what was seen to be the severity of the Neo Classicists but the principal initiators of this ‘New’, most attractive and impressive period of British Sculpture, were Jules Dalou who taught at The South Kensington School of Art, for eight years from 1871, his friend Édouard Lantéri, who taught at The National Art Training College (later renamed The Royal College of Art) and Alfred Stevens. The result was, as one critic has said, ‘a perfect synthesis of the spiritual and the sensual’. This approach to the subject was adopted by the ‘New’ sculptors. -

Nathaniel Hitch and the Making of Church Sculpture Jones, Claire

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of Birmingham Research Portal Nathaniel Hitch and the making of church sculpture Jones, Claire DOI: 10.16995/ntn.733 License: Creative Commons: Attribution (CC BY) Document Version Peer reviewed version Citation for published version (Harvard): Jones, C 2016, 'Nathaniel Hitch and the making of church sculpture', 19: interdisciplinary studies in the long nineteenth century. https://doi.org/10.16995/ntn.733 Link to publication on Research at Birmingham portal Publisher Rights Statement: All Open Library of Humanities content is released under open licenses from Creative Commons. General rights Unless a licence is specified above, all rights (including copyright and moral rights) in this document are retained by the authors and/or the copyright holders. The express permission of the copyright holder must be obtained for any use of this material other than for purposes permitted by law. •Users may freely distribute the URL that is used to identify this publication. •Users may download and/or print one copy of the publication from the University of Birmingham research portal for the purpose of private study or non-commercial research. •User may use extracts from the document in line with the concept of ‘fair dealing’ under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 (?) •Users may not further distribute the material nor use it for the purposes of commercial gain. Where a licence is displayed above, please note the terms and conditions of the licence govern your use of this document. When citing, please reference the published version. -

1934 Exhibition Catalogue Pdf, 1.23 MB

~ i Royal Cambrian Academy of Art, t PL:\S MAWR, CON\\'AY. t Telephone, No. 113 Conway. i CATALOGUE i OF THE I FIFTY-SECOND ANNUAL i EXHIB ITION, 1934. ~ i The Exhibition will be open from 21st May to I ~ 26th September. A dmission (including Enter- .( ,r tainment Tax), Adults, 7d. Children under 14, ~ ltd. Season Tickets, 2 /(i. 1' ,q·~~"-"15'~ <:..i!w~~~~~~~~\:I R. E. Jones & Bros., Pri11te1·s, Conway. 1 HONORARY MEMBERS. ', The Presidents of the following Academies and Societies :- - Royal Academy of Arts, London (Sir W. Llewelyn, G.C.V.O ., R.I., R.W.A.). ii Royal Scottish Academy, Edinburgh (George Pirie, Esq). Royal Hibernian Academy, Dublin (Dermod O'Brien, Esq.,H.R.A., H.R.S.A.). tbe Royal Cambrian Rccldemy or Jlrf, F. Brangwyn, Esq., R.A., H.R.S.A., R.E., R.W.A., A.R.W.S. INSTITUTED 1881. Sir W. Goscombe John, R.A. Terrick Williams, Esq., R .A., F'.R.I., R.O.I., R.W.A., V.P.R.13.C. Sir Herbert Baker, R.A., F.R.I.B.A. PATRONS. FOUNDERS. HIS MAJESTY THE KING W. Laurence Banks, J .P. HER MAJESTY THE QUEEN Sir Cuthbert Grundy, R.C.A., R.I., R.W.A., V.P.R.13.C. , . HIS ROYAL HIGHNESS THE PRINCE J. R. G. Grundy, R.C.A. OF WALES Anderson Hague, V .P .R.C.A., R.I., R.O.I. E. A. Norbury, R.C.A. Charles Potter, R.C.A. I, I, H. Clarence Whaite, P.R.C.A., R.W.S. -

HISTORIC RESOURCE PROJECT ASSESSMENT St

HISTORIC RESOURCE PROJECT ASSESSMENT St. James Park Capital Vision and Performing Arts Pavilion Project San José, Santa Clara County, California Prepared for: Department of Parks, Recreation and Neighborhood Services City of San José 200 East Santa Clara St. San José, CA 95113 C/o David J. Powers & Associates, Inc. 04.05.2019 (revised 08.12.2019) ARCHIVES & ARCHITECTURE, LLC PO Box 1332 San José, CA 95109-1332 St. James Park Historic Resource Project Assessment Table of Contents Table of Contents HISTORIC RESOURCE PROJECT ASSESSMENT ...................................................................... 1 Table of Contents ........................................................................................................................... 2 Introduction ..................................................................................................................................... 3 Project Description...................................................................................................................... 4 Purpose and Methodology of this Study ..................................................................................... 6 Previous Surveys and Historical Status ...................................................................................... 6 Location Map .............................................................................................................................. 8 Summary of Findings ................................................................................................................. -

Obama Presidential Library the University of Chicago Adjaye Associates Contents I Urban Ii Library Iii Net-Zero Iv Design Approach in the Park Strategy Vision

OBAMA PRESIDENTIAL LIBRARY THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO ADJAYE ASSOCIATES CONTENTS I URBAN II LIBRARY III NET-ZERO IV DESIGN APPROACH IN THE PARK STRATEGY VISION OBAMA PRESIDENTIAL LIBRARY │ THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO │ ADJAYE ASSOCIATES 2 I URBAN APPROACH OUR PROPOSAL RE-IMAGINES THE PRESIDENTIAL LIBRARY TO BE THE FIRST TRUE URBAN LIBRARY. OPERATING ON MULTIPLE SCALES OF RENEWAL — INDIVIDUAL, URBAN, ECONOMIC, AND ECOLOGICAL — THE NEW LIBRARY ACTIVELY ENGAGES THE COMMUNITY WITH UPDATED INFRASTRUCTURE AND NEW BUSINESS OPPORTUNITIES FOR THE FUTURE GENERATIONS OF THE SOUTH SIDE OF CHICAGO. OBAMA PRESIDENTIAL LIBRARY │ THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO │ ADJAYE ASSOCIATES 3 WASHINGTON PARK SOUTH SIDE OF CHICAGO WASHINGTON PARK • 7 MILES SOUTH OF THE LOOP • NEAR MIDWAY AIRPORT • HISTORICALLY SIGNIFICANT SITE • GATEWAY TO THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO • EASILY ACCESSIBLE BY PUBLIC TRANSPORTATION OBAMA PRESIDENTIAL LIBRARY │ THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO │ ADJAYE ASSOCIATES 4 GARFIELD BOULEVARD HISTORICALLY OBAMA PRESIDENTIAL LIBRARY │ THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO │ ADJAYE ASSOCIATES 5 GARFIELD BOULEVARD TODAY OBAMA PRESIDENTIAL LIBRARY │ THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO │ ADJAYE ASSOCIATES 6 WASHINGTON PARK “LUNGS OF THE CITY” WASHINGTON PARK • CONSTRUCTED IN 1870’S • DR. JOHN RAUCH THE FOREFATHER OF THE CHICAGO PARK SYSTEM DESCRIBED IT AS “THE LUNGS OF THE CITY” • DESIGNED BY FREDERICK LAW OLMSTED & CALVERT VAUX • EARLY ATTRACTIONS TO THE PARK INCLUDED RIDING STABLES, CRICKET GROUNDS, BASEBALL FIELDS, A TOBOGGAN SLIDE, ARCHERY RANGES, A GOLF COURSE, BICYCLE PATHS, ROW BOATS, -

George Tinworth: an Artist in Terracotta Miranda F Goodby

George Tinworth: an Artist in Terracotta Miranda F Goodby eorge Tinworth, Doulton's premier artist at the Lambeth stud ios between 1867 and 1913, Gdevoted his life to large sca le religious and memorial sculptures . Today he is better kn own for his small humorous animal figures and vase designs - but this wa s not always the case. At th e height of his career in the 1870s and '80s, George Ti nworths work wa s bought by royalty and major museums in Great Britain and North America; he was receiving commissions from important churches and other institutions for sculptural work and he was popular with both the public and the critics. He wa s described by John Forbes Robinson as, 'Rembrandt in clay and unquestionably th e most original modeller that England has yet produced'.' Ed mund Gosse called him, 'a painter in terra cotta? and likened him to Ghiberti, while John Ruskin described his work as, 'full of fire and zealous faculty' ..1 He won several medals during his tim e at the Royal Academ y of Art and later, when working at Doulton 's, hi s sculptures for the grea t national and internat ional exhibiti on s were regularly singled out for praise and pri zes. In 1878 he was made a member of the French Academie des Beaux Art s, and in 1893 Lambeth Parish C ou ncil named a s treet in hi s honour.' By the time of his death in 1913, critical taste Figure 1 George Tintoorth il1 his studio uiorking 011 the had ch anged. -

Banffshire Field Club Transactions 1893-1900

Transactions OF THE BANFFSHIRE FIELD CLUB. THE STRATHMARTINE BanffshireTRUST Field Club The support of The Strathmartine Trust toward this publication is gratefully acknowledged. www.banffshirefieldclub.org.uk 23 of the family history. This Mr Edgar Shand's grandfather emigrated to Nova Scotia from Huntly or Banff in the year 1794 or 1795. Another Shand of Northern origin and who is much interested in the family history is Mr J. L, Shand'. of Messrs Shand, Haldane, & Co., 24, Rood Lane, London. THE FAMILY OF RHIND. EARLY NOTICES OF THE SURNAME OF RHIND. The family of Rhind is by many supposed to have originated in the Low Countries; but the probability is greater that the name is of native origin, and derived either from the parish of Rynd, in Perth- shire, or from the estate of Rhind (in 1509' Rynde)', in Fifeshire. The name is said to signify in Gaèlìc ' a point,' 1365.—In the Register of the Privy Council' of Scotland, Patrick Rynd appears in 1365 as bailie of Forfar. In Robertson's Index of Charters Sub David II. (1329-1370) appears notice of a charter to "Marthacus Rind' of four oxengate of land of Cass and four oxengate in the forest of Platter, in the County of Forfar; also, a similar charter to Murthaens del Rynd granted at Dundeè on the 31st of July and in the 37th year of the reign of the same sovereign (1365), the reddendo in the latter case being of albarum cirothecarum, or 2d. in silver, in name of blench, only if asked, and at 'our manor of Forfar.' 1415 — Alexander de Rend, Knight, is witness to a deed dated at Aberdeen 6th February 1415 (Register of the Bishopric of Moray). -

Design for Eltham Palace Frieze £1,750 REF: 1527 Artist: GILBERT LEDWARD

Design for Eltham Palace Frieze £1,750 REF: 1527 Artist: GILBERT LEDWARD Height: 12.5 cm (4 1/1") Width: 49.5 cm (19 1/2") Framed Height: 36 cm - 14 1/4" Framed Width: 67 cm - 26 1/2" 1 Sarah Colegrave Fine Art By appointment only - London and North Oxfordshire | England +44 (0)77 7594 3722 https://sarahcolegrave.co.uk/design-for-eltham-palace-frieze 01/10/2021 Short Description GILBERT LEDWARD, RA, PRBS (1888-1960) Tennis, Golf, Shooting, Ice-Skating, Dreaming – Proposed Design for Decorative Frieze in the Italian Drawing Room at Eltham Palace, commissioned by Stephen Courtauld Signed and dated July 9th 1933 Watercolour and pencil 12.5 by 49.5 cm., 5 by 19 ½ in. (frame size 36 by 67 cm., 14 ¼ by 26 ¼ in.) Exhibited: The artist’s daughter; London, The Fine Art Society, A Centenary Tribute, Feb 1988, no. 43. Gilbert Ledward was born in London. He was educated at St Mark’s College, Chelsea. In 1905 he entered the Royal College of Art to study sculpture under Edouard Lanteri and in 1910 he entered the Royal Academy Schools. In 1913 he won the Prix de Rome for sculpture, the Royal Academy’s travelling award and gold medal, which allowed him to travel in Italy until the outbreak of the Wold War I. During the war he served as a lieutenant in the Royal Garrison Artillery and was appointed as an official war artist in 1918. Following the war he was largely occupied as a sculptor of war memorials including the Guards Division memorial in St James’s Park and the Household Division’s memorial in Horse Guards Parade. -

The Scottish Genealogist

THE SCOTTISH GENEALOGY SOCIETY THE SCOTTISH GENEALOGIST INDEX TO VOLUMES LIX-LXI 2012-2014 Published by The Scottish Genealogy Society The Index covers the years 2012-2014 Volumes LIX-LXI Compiled by D.R. Torrance 2015 The Scottish Genealogy Society – ISSN 0330 337X Contents Please click on the subject to be visited. ADDITIONS TO THE LIBRARY APPRECIATIONS ARTICLE TITLES BOOKMARKS BOOK REVIEWS CONTRIBUTORS FAMILY TREES GENERAL INDEX ILLUSTRATIONS INTRODUCTION QUERIES INTRODUCTION Where a personal or place name is mentioned several times in an article, only the first mention is indexed. LIX, LX, LXI = Volume number i. ii. iii. iv = Part number 1- = page number ; - separates part numbers within the same volume : - separates volume numbers BOOKMARKS The contents of this CD have been bookmarked. Select the second icon down at the left-hand side of the document. Use the + to expand a section and the – to reduce the selection. If this icon is not visible go to View > Show/Hide > Navigation Panes > Bookmarks. Recent Additions to the Library (compiled by Joan Keen & Eileen Elder) LIX.i.43; ii.102; iii.154: LX.i.48; ii.97; iii.144; iv.188: LXI.i.33; ii.77; iii.114; Appreciations 2012-2014 Ainslie, Fred LIX.i.46 Ferguson, Joan Primrose Scott LX.iv.173 Hampton, Nettie LIX.ii.67 Willsher, Betty LIX.iv.205 Article Titles 2012-2014 A Call to Clan Shaw LIX.iii.145; iv.188 A Case of Adultery in Roslin Parish, Midlothian LXI.iv.127 A Knight in Newhaven: Sir Alexander Morrison (1799-1866) LXI.i.3 A New online Medical Database (Royal College of Physicians)