Redalyc.Nuyorican Spaces: Mapping Identity in a Poetic Geography

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Puerto Ricans at the Dawn of the New Millennium

puerto Ricans at the Dawn of New Millennium The Stories I Read to the Children Selected, Edited and Biographical Introduction by Lisa Sánchez González The Stories I Read to the Children documents, for the very first time, Pura Belpré’s contributions to North Puerto Ricans at American, Caribbean, and Latin American literary and library history. Thoroughly researched but clearly written, this study is scholarship that is also accessible to general readers, students, and teachers. Pura Belpré (1899-1982) is one of the most important public intellectuals in the history of the Puerto Rican diaspora. A children’s librarian, author, folklorist, translator, storyteller, and puppeteer who began her career the Dawn of the during the Harlem Renaissance and the formative decades of The New York Public Library, Belpré is also the earliest known Afro-Caribeña contributor to American literature. Soy Gilberto Gerena Valentín: New Millennium memorias de un puertorriqueño en Nueva York Edición de Carlos Rodríguez Fraticelli Gilberto Gerena Valentín es uno de los personajes claves en el desarrollo de la comunidad puertorriqueña Edwin Meléndez and Carlos Vargas-Ramos, Editors en Nueva York. Gerena Valentín participó activamente en la fundación y desarrollo de las principales organizaciones puertorriqueñas de la postguerra, incluyendo el Congreso de Pueblos, el Desfile Puertorriqueño, la Asociación Nacional Puertorriqueña de Derechos Civiles, la Fiesta Folclórica Puertorriqueña y el Proyecto Puertorriqueño de Desarrollo Comunitario. Durante este periodo también fue líder sindical y comunitario, Comisionado de Derechos Humanos y concejal de la Ciudad de Nueva York. En sus memorias, Gilberto Gerena Valentín nos lleva al centro de las continuas luchas sindicales, políticas, sociales y culturales que los puertorriqueños fraguaron en Nueva York durante el periodo de a Gran Migracíón hasta los años setenta. -

Code-Switching and Translated/Untranslated Repetitions in Nuyorican Spanglish

E3S Web of Conferences 273, 12139 (2021) https://doi.org/10.1051/e3sconf/202127312139 INTERAGROMASH 2021 Code-switching and translated/untranslated repetitions in Nuyorican Spanglish Marina Semenova* Don State Technical University, 344000, Rostov-on-Don, Russia Abstract. Nuyorican Spanglish is a variety of Spanglish used primarily by people of Puerto Rican origin living in New York. Like many other varieties of the hybrid Spanglish idiom, it is based on extensive code- switching. The objective of the article is to discuss the main features of code-switching as a strategy in Nuyrican Spanglish applying the methods of linguistic, componential, distribution and statistical analysis. The paper focuses on prosiac and poetic texts created in Nuyrican Spanglish between 1978 and 2020, including the novel Yo-Yo Boing! by Giannina Braschi and 142 selected Boricua poems, which allows us to make certain observations on the philosophy and identity of Nuyorican Spanglish speakers. As a result, two types of code-switching as a strategy are denoted: external and internal code-switching for both written and oral speech forms. Further, it is concluded that repetition, also falling into two categories (translated and untranslated), embodies the core values of Nuyorican Spanglish (freedom of choice and focus on the linguistic personality) and reflects the philosophical basis for code-switching. 1 Introduction Nuyorican Spanglish is a Spanglish dialect used in New York’s East Side primarily by people of Puerto Rican origin, many of who are first- or second-generation New Yorkers. This means that Spanglish they use is rather the most effective way to communicate between English and Spanish cultures which come into an extremely intense contact in this cosmopolitan city. -

Introduction

Introduction Frederick Luis Aldama Scholar, playwright, spoken-word performer, award-winning poet, and avant-garde fiction author, since the 1980s Giannina Braschi has been creating up a storm in and around a panoply of Latinx hemispheric spaces. Her creative corpus reaches across different genres, regions, and historical epochs. Her critical works cover a wide range of subjects and authors, including Miguel de Cervantes, Garcilaso de la Vega, Juan Ramón Jiménez, Gustavo Adolfo Bécquer, Antonio Machado, César Vallejo, and García Lorca. Her dramatic poetry titles in Spanish include Asalto al tiempo (1981) and La comedia profana (1985). Her radically ex- perimental genre-bending titles include El imperio de los sueños (1988), the bilingual Yo-Yo Boing! (1998), and the English-penned United States of Banana (2011). With national and international awards and works ap- pearing in Swedish, Slovenian, Russian, and Italian, she is recognized as one of today’s foremost experimental Latinx authors. Her vibrant bilingually shaped creative expressions and innovation spring from her Latinidad, her Puerto Rican-ness that weaves in and through a planetary aesthetic sensibility. We discover as much in her work about US/Puerto Rico sociopolitical histories as we encounter the metaphysical and existential explorations of a Cervantes, Rabelais, Did- erot, Artaud, Joyce, Beckett, Stein, Borges, Cortázar, and Rosario Castel- lanos, for instance. With every flourish of her pen Braschi reminds us that in the distillation and reconstruction of the building blocks of the uni- verse there are no limits to what fiction can do. And, here too, the black scratches that form words and carefully composed blank spaces shape an absent world; her strict selection out of words and syntax is as important as the precise insertion of words and syntax to put us into the shoes of the “complicit reader” (Julio Cortázar’s term) to most productively interface, invest, and fill in the gaps of her storyworlds. -

College of Arts and Sciences

60 Study Abroad All students planning international study are strongly ate courses both here at Fairfield University and your encouraged to plan ahead to maximize program oppor- destination . Be sure to attend the Study Abroad Fair tunities and to ensure optimal match of major, minor, in September and attend a Study Abroad 101 session . previous language studies and intended destination . For Sophomores: attend a Study Abroad 101 meeting Study abroad is intended to build upon and enhance to get information about the application process and majors and minors and for this reason, program the steps required before your departure . Learn about choices will be carefully reviewed to ensure fit between your options and discuss them with your academic academics and destination . advisor, faculty, and family . For fall/spring programs in your Junior year: the deadline in February 1 . For Credits for studying abroad will only be granted for Juniors: you may study abroad during the fall of your academic work successfully completed in approved senior year at Fairfield programs for which grades international programs . All coursework must receive as well as credits are recorded . Applications are due pre-approval (coordinated through the International February 1 of Junior year to go abroad Fall of Senior Programs Office) . Only pre-approved courses, taken at year . To learn more about all our semester, summer, an approved program location, will be transcripted and spring break and intersession programs, consult with a accepted into a student’s curriculum . study abroad advisor or visit the study abroad website Fairfield University administers its own programs in for the current offerings . -

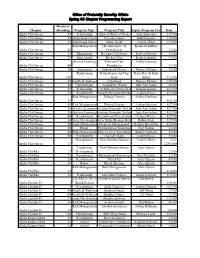

S08 Chapter Programming Report

Office of Fraternity Sorority Affairs Spring 08 Chapter Programming Report Members Chapter Attending Program Type Program Title Chapter Program Cord. Date Alpha Chi Omega 45 Scholarship How to Write a Check Judy Sukovich 1/27/08 Alpha Chi Omega 25 Sisterhood Event Pancake Dinner Juaki Kapadia 1/28/08 Alpha Chi Omega 35 Sisterhood Mixer Game Night Jennifer Ross 2/15/08 Risk Management The Importance of Kathleen Mullen Alpha Chi Omega 45 Checking In 3/2/08 Alpha Chi Omega 33 Educational By Law Cliff Notes Kaitlyn Herthel 3/3/08 Alpha Chi Omega 33 Educational By-Law Day Kaitlyn Herthel 3/3/08 Service Learning Embrace Kids Ashley Garrison Alpha Chi Omega 40 Foundation 3/9/08 Alpha Chi Omega 20 Sisterhood Sisterhood Dinner Monica Milano 3/9/08 Fundraising Philanthropy and Flap Katie Karr & Judy Alpha Chi Omega 188 Jacks Adam 3/12/08 Alpha Chi Omega 38 Health & Wellness Sisterhood Monica Milano 3/29/08 Alpha Chi Omega 84 Philanthropy Around the World Judy Ann Adam 4/2/08 Alpha Chi Omega 55 ScholarshipHow to Write the Perfect E-MailJennifer Kantor 4/13/08 Alpha Chi Omega 25 Recruitment Sorority Recruitment Fair Lauren Ricca 4/15/08 Risk Management Taking Chances Ashley Garrison Alpha Chi Omega 27 4/21/08 Alpha Chi Omega 43 Risk Management Hazing Policies Ashley Garrison 4/27/08 Alpha Chi Omega 36 Service LearningPreventing Domestic Violence Judy Ann Adam 4/27/08 Alpha Chi Omega 36 Service LearningPreventing Domestic Violence Judy Ann Adam 4/27/08 Alpha Chi Omega 40 Recruitment Recruitment Presentation Lauren Ricca 4/27/08 Alpha Chi Omega 30Career -

Latino Subgroups Political Participation in American Politics

University of South Florida Scholar Commons Graduate Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 3-23-2017 Latino Subgroups Political Participation in American Politics: The Other Latinos’ Electoral Behavior Angelica Maria Leon Velez University of South Florida, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd Part of the Latin American Studies Commons Scholar Commons Citation Leon Velez, Angelica Maria, "Latino Subgroups Political Participation in American Politics: The Other Latinos’ Electoral Behavior" (2017). Graduate Theses and Dissertations. http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd/6723 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Latino Subgroups Political Participation in American Politics: The Other Latinos’ Electoral Behavior by Angelica Maria Leon Velez A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Institute for the Study of Latin American and the Caribbean with a Concentration in Government and International Affairs College of Arts and Sciences University of South Florida Major Professor: Bernd Reiter, Ph.D. Rachel May, Ph.D. Heide Castaneda, Ph.D. Steven Tauber, Ph.D. Date of Approval: March 21, 2017 Keywords: Latinidad, group identity, voting behavior, Latino politics, Latino Studies Copyright © 2017, Angelica Leon Velez DEDICATION I dedicate this work to my family, they have been my biggest supporter’s. To my mother who migrated to this country more than ten years ago, and worked so hard to pay for my education. -

Sample Catalyst 210 Courses

Fall 2017-2018 Catalyst Course Descriptions Catalyst 210 – Intercultural Competence M W F 11:15AM – 12:25PM R 1:05PM – 1:55PM CTL 210.01: Pickers & Artists: Culture in Antiques and Art Professor Clark Four credits This class will examine how groups of people have been culturally represented in antiques, collectibles, art, and design. Topics to be addressed include: (1) how groups, such as American Indians, African Americans, “Hillbillies,” Women, Arabs and/or Muslims, Latinx, and others have been represented in collectibles and antiques, as well as art and design; (2) how cultural representations have been used to stereotype group members and reinforce power differences; (3) how these representations have been used for cultural appropriation; and (4) how groups reclaim representations of themselves. Professor Clark’s section will emphasize these issues from a sociological perspective. The class will meet jointly with Professor Oblinger’s section on a regular basis. CTL 210.02: Pickers & Artists: Culture in Antiques and Art Professor Oblinger Four credits This class will examine how groups of people have been culturally represented in antiques, collectibles, art, and design. Topics to be addressed include: (1) how groups, such as American Indians, African Americans, “Hillbillies,” Women, Arabs and/or Muslims, Latinx, and others have been represented in collectibles and antiques, as well as art and design; (2) how cultural representations have been used to stereotype group members and reinforce power differences; (3) how these representations have been used for cultural appropriation; and (4) how groups reclaim representations of themselves. Professor Oblinger’s section will emphasize these issues from the view point of the artist and the public. -

Puerto Ricans in Orlando and Central Florida

Centro de Estudios Puertorriqueños Hunter College (CUNY) Policy rePort | VOLUMe 1 | No. 1 |sPriNg 2006 Puerto Ricans in Orlando and Central Florida Jorge Duany Félix V. Matos-roDríguez Puerto Ricans in Orlando and Central Florida Jorge Duany Department of sociology and Anthropology University of Puerto rico, río Piedras This report was sponsored by the Orlando Regional Chamber of Commerce and Orange County Government. Félix V. Matos-roDríguez centro de estudios Puertorriqueños Hunter college, city University of New york Contents Summary of Main Findings . 2 Acknowledgments . 5 Introduction . 5 Changing Settlement Patterns . 8 Historical Background . 12 Centro de Estudios Puertorriqueños A Contemporary Socioeconomic Portrait . 15 Hunter College (CUNY) Political Incorporation . 22 695 Park Avenue, Room E-1429 New York, New York 10021 Cultural Identities . 24 212.772.5686 Toward a New Research Agenda . 26 www.centropr.org Conclusion . 29 Notes . 30 References . 33 Biographical Sketches . 39 ...2... ...1... SUMMARY OF MAIN FINDINGS • Between 1990 and 2000, the city of orlando experienced the largest increase (142 percent) in the number of Puerto ricans • During the 1990s, Florida displaced New Jersey as the second largest stateside. today, orlando is the fourth-largest metropolitan concentration of Puerto ricans in the U.s. mainland (after New york). area for Puerto ricans in the United states, after New york city, Florida’s Puerto rican population grew from slightly more than 2 percent Philadelphia, and chicago. of all stateside Puerto ricans in 1960 to more than 14 percent in the year • Puerto rican migration to central Florida is not highly selective by sex. 2000. Furthermore, the number of Puerto rican residents in Florida island-born and mainland-born residents have very similar proportions rose from 482,027 in 2000 to 571,755 persons in 2003. -

De-Conflating Latinos/As' Race and Ethnicity

UCLA Chicana/o Latina/o Law Review Title Los Confundidos: De-Conflating Latinos/As' Race and Ethnicity Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/9nx2r4pj Journal Chicana/o Latina/o Law Review, 19(1) ISSN 1061-8899 Author Sandrino-Glasser, Gloria Publication Date 1998 DOI 10.5070/C7191021085 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California LOS CONFUNDIDOS: DE-CONFLATING LATINOS/AS' RACE AND ETHNICITY GLORIA SANDRmNO-GLASSERt INTRODUCTION ......................................................................................71 I. LATINOS: A DEMOGRAPHIC PORTRAIT ..............................................75 A. Latinos: Dispelling the Legacy of Homogenization ....................75 B. Los Confundidos: Who are We? (Qui6n Somos?) ...................77 1. Mexican-Americans: The Native Sons and D aughters .......................................................................77 2. Mainland Puerto Ricans: The Undecided ..............................81 3. Cuban-Americans: Last to Come, Most to Gain .....................85 II. THE CONFLATION: AN OVERVIEW ..................................................90 A. The Conflation in Context ........................................................95 1. The Conflation: Parts of the W hole ..........................................102 2. The Conflation Institutionalized: The Sums of All Parts ...........103 B. The Conflation: Concepts and Definitions ...................................104 1. N ationality ..............................................................................104 -

On out of Focus Nuyoricans, Noricuas, and Performance Identities

Liminalities: A Journal of Performance Studies Vol. 10, No. 3/4 (2014) On Out of Focus Nuyoricans, Noricuas, and Performance Identities Urayoán Noel Nuyorican poetics have long been bound up in questions of visibility and invisibility. This is partly a sociological matter reflective of the reality of a New York Puerto Rican community that has historically struggled for (counter)institutional visibility even against the backdrop of a variety of hyper- visible and powerful yet stereotype-defining media representations, from the punchlines of West Side Story to the ethnographic solemnity of Oscar Lewis’s La Vida; A Puerto Rican Family in the Culture of Poverty—San Juan and New York (1966). In Miguel Algarín’s foundational formulation of the Nuyorican aesthetic, performed poetry (and the various other kinds of spoken word and performance that flourished at his Nuyorican Poets Cafe) emerges as an alternative to the impasses of communal visibility/invisibility; his essay “Nuyorican Literature” (1981) theorizes Nuyorican poetics in terms of communal performance, of reading aloud, of the public sharing of poetry as a means of collective healing.1 As a founding Nuyorican poet and author of the Nuyorican movement’s foundational epic “Puerto Rican Obituary” (1969), Pedro Pietri (1943-2004) shared Algarín’s community- and performance-centric conception of poetry, but Pietri’s own poetics also opened up towards conceptualist, experimental, and Urayoán Noel is Assistant Professor of English and Spanish at NYU. He is the author of In Visible Movement: Nuyorican Poetry from the Sixties to Slam (University of Iowa Press, 2014) and of several books of poetry. -

Nuyorican and Diasporican Literature and Culture E

Nuyorlcan and Diasporican Uterature and Culture Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Literature Nuyorican and Diasporican Literature and Culture e Jorge Duany Subject: American Literature, Literary Studies (20th Centwy Onward) Online Publication Date: jan 2018 DOI: 10.1093/acrefore/9780190201098.013.387 Summary and K.eywords The term "Nuyorican" (in its various spellings) refers to the cornbination of "Puerto Rican" and "NewYorker." The sobriquet became a popular shorthand for the Puerto Rican exodus to the United States after World War II. Since the mid-1960s, the neologism became associated with the literary and artistic movement known as "Nuyorican." The movement was institutionalized with the 1973 founding ofthe Nuyorican Poets Café in the Lower East Side of Manhattan by Miguel Algarín and Miguel Piñero. Much of Nuyorican literature featured frequent autobiographical references, the predominance of the English language, street slang, realism, parodie humor, subversiva politics, and a ruptura with the island's literary models. Since the 1980s, the literature of the Puerto Rican diaspora has been characterized as "post-Nuyorican" or "Diasporican" to capture sorne of its stylistic and thematic shifts, including a movement away from urban blight. violence, colloquialism, and radicalism. The Bronx-born poet Maria Teresa ("Mariposa") Fernández coined the term "Diasporican" in a celebrated 1993 poem. Contemporary texts written by Puerto Ricans in the United States also reflect their growing dispersa! from their initial concentration in New York City. Keywords: Puerto Rican diaspora, Puerto Ricans in New York. second-generation immigrants, retum migration to Puerto Rico Pago 1 of22 PRINTED PROM the OXFORD RESEARCH ENCYCLOPEDIA, LITERATURE (literature.oxfordre.com). (e) Oxford University Press USA. -

Islanders Blame Nuyoricans

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 456 178 UD 034 350 AUTHOR Verin-Shapiro, Penny TITLE Why "Nuyoricans" Are Given the Cold-Shoulder by Other Puerto Ricans. SPONS AGENCY National Inst. of Mental Health (DHHS), Rockville, MD. PUB DATE 2000-02-00 NOTE 32p.; In: National Association of African American Studies & National Association of Hispanic and Latino Studies: 2000 Literature Monograph Series. Proceedings (Social Studies Section)(Houston, TX, February 21-26, 2000). CONTRACT 1-F31-MH11465-01 PUB TYPE Reports Descriptive (141) Speeches/Meeting Papers (150) EDRS PRICE MF01/PCO2 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Cultural Differences; Cultural Images; Ethnic Stereotypes; *Ethnicity; Hispanic Americans; Immigrants; *Puerto Rican Culture; *Puerto Ricans; Social Discrimination IDENTIFIERS New York; *Nuyoricans ABSTRACT Based on ethnographic research on Puerto Ricans on the island and mainland, this paper examines why Nuyoricans' identities are disparaged by island and mainland Puerto Ricans. Nuyoricans are Puerto Ricans, especially in New York, who mix North American and Puerto Rican cultural traits. Many have grown up traveling between the island and mainland. One reason that Puerto Ricans tend to reject Nuyoricans is the negative stereotypes assigned to Nuyoricans from which other Puerto Ricans wish to distance themselves. Also, in many Puerto Ricans' eyes, the Nuyorican represents what is considered worst about the dominant North American culture and a betrayal of traditional Puerto Rican ways. Commentary on Nuyoricans is really commentary on Puerto Rico's relationship with the United States and its effect on the Puerto Rican culture. The Nuyorican brings the authenticity of today's Puerto Rican into question due to extensive interaction with the United States.