Mogadishu, Somalia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

East and Central Africa 19

Most countries have based their long-term planning (‘vision’) documents on harnessing science, technology and innovation to development. Kevin Urama, Mammo Muchie and Remy Twingiyimana A schoolboy studies at home using a book illuminated by a single electric LED lightbulb in July 2015. Customers pay for the solar panel that powers their LED lighting through regular instalments to M-Kopa, a Nairobi-based provider of solar-lighting systems. Payment is made using a mobile-phone money-transfer service. Photo: © Waldo Swiegers/Bloomberg via Getty Images 498 East and Central Africa 19 . East and Central Africa Burundi, Cameroon, Central African Republic, Chad, Comoros, Congo (Republic of), Djibouti, Equatorial Guinea, Eritrea, Ethiopia, Gabon, Kenya, Rwanda, Somalia, South Sudan, Uganda Kevin Urama, Mammo Muchie and Remy Twiringiyimana Chapter 19 INTRODUCTION which invest in these technologies to take a growing share of the global oil market. This highlights the need for oil-producing Mixed economic fortunes African countries to invest in science and technology (S&T) to Most of the 16 East and Central African countries covered maintain their own competitiveness in the global market. in the present chapter are classified by the World Bank as being low-income economies. The exceptions are Half the region is ‘fragile and conflict-affected’ Cameroon, the Republic of Congo, Djibouti and the newest Other development challenges for the region include civil strife, member, South Sudan, which joined its three neighbours religious militancy and the persistence of killer diseases such in the lower middle-income category after being promoted as malaria and HIV, which sorely tax national health systems from low-income status in 2014. -

In (Hc Abscncc of Any Other Rcqucst to Speak. the Prc\Idcnt ;\Djourncd The

Part II 25s _-. .-_--.--.-_---. __. -. In (hc abscncc of any other rcqucst to speak. the At ths came meeting. the rcprcsentativc of F-rancc Prc\idcnt ;\djourncd the deb;ltc. sn)ing th<it the Security rcvicucd the background of the matter and stntrd that ( (1unc11 would rcm;rin scilcd of the quc\~~on 50 that II In IIcccmbcr 1974, the l,rcnch Government had organ- mlpht rc\umc con~ldcrntion of it :it any appropriate ~/cd a conhuttation of thz Comorian population which llrne.“‘-“‘ rcsultcd in a large majority in Favour of indcpendencc. Howcvcr. two thirds of the votes in the island of klayotte were negative. The French parliament adopted Decision of 6 I:ebruary 1976 ( IHHXth meeting): rcJcc- on 30 June I975 a law providing for the drafting of a lion of c-Power draft resolution constitution prcscrving the political and administrative In a telegram’Oz’ dated 28 January 1976, the Head of rdentit) of the islands. Although only the French State of the Comoros informed the President of the parliament could decide to transfer sovereignty, the Security Council that the French Govcrnmcnt intended Chamber of Deputies of the Comoros proclaimed the TV, organilr a referendum in the island of Mayotte on 8 independence of the island> on 5 July 1975. I’sbruary 1976. tie pointed out that Muyottc was an On 31 Dcccmbcr. the French Government recognired lntcgral part of Comorian territory under French laws the indcpcndcnce of the islands of Grandc-Comore, and that on I2 November 1975, the linitcd Nations had Anjouan. and Mohfli but provided for the pcoplc of admitted the C‘omorian State consisting of the four Mayottc to make a choice between the island remaining lhland:, of Anjouan, Mayottc. -

A New Deal for Somalia? : the Somali Compact and Its Implications for Peacebuilding

NEW YORK UNIVERSITY i CENTER ON INTERNATIONAL COOPERATION A New Deal for Somalia? : The Somali Compact and its Implications for Peacebuilding Sarah Hearn and Thomas Zimmerman July 2014 NEW YORK UNIVERSITY CENTER ON INTERNATIONAL COOPERATION The world faces old and new security challenges that are more complex than our multilateral and national institutions are currently capable of managing. International cooperation is ever more necessary in meeting these challenges. The NYU Center on International Cooperation (CIC) works to enhance international responses to conflict, insecurity, and scarcity through applied research and direct engagement with multilateral institutions and the wider policy community. CIC’s programs and research activities span the spectrum of conflict, insecurity, and scarcity issues. This allows us to see critical inter-connections and highlight the coherence often necessary for effective response. We have a particular concentration on the UN and multilateral responses to conflict. Table of Contents A New Deal for Somalia? : The Somali Compact and its Implications for Peacebuilding Sarah Hearn and Thomas Zimmerman Introduction 2 The Somali New Deal Compact 3 Process 3 Implementation to Date 5 Trade-offs 6 Process 6 Risks 7 Implementation 8 External Actors’ Perspectives on Trade-offs 9 Somali Actors’ Perspectives on Trade-offs 9 Conclusions 10 Endnotes 11 Acknowledgments 11 Introduction In balancing these trade-offs, we highlight the need for Somalis to articulate priorities (not just programs, but In this brief,1 we analyze the process that led to the also processes) to advance confidence building. Low “Somali New Deal Compact,” the framework’s potential trust among Somalis, and between Somalis and donors, effectiveness as a peacebuilding tool, and potential ways will stymie cooperation on any reform agenda, because to strengthen it. -

Somalia: COVID-19 Impact Update No. 14 (November 2020)

SOMALIA COVID-19 Impact Update No. 14 November 2020 This report on the Country Preparedness & Response Plan (CPRP) for COVID-19 in Somalia is produced monthly by OCHA and the Integrated Office in collaboration with partners. It contains updates on the response to the humanitarian and socio-economic impact of COVID-19, covering the period from 25 October to 25 November 2020. The next report will be issued in early January 2021. Highli ghts Locations of functional isolation sites Source: OCHA • Somalia’s informal economy, based on remittances, foreign imports and agriculture, has been heavily impacted by COVID-19. Reflecting gender inequalities in the country, women-owned Hargeysa Somaliland businesses were especially hard-hit, with 98 per cent reporting Puntland reduced revenue. • The COVID-19 pandemic has exacerbated mental distress as Gaalkacyo people living in vulnerable circumstances, including the elderly and Galmudug Galgaduud persons with disabilities, are separated from their caregivers due to State Since March 2020: quarantine and isolation requirements. 4662 reported cases Hir-Shabelle State 124 deaths • The US$256 million humanitarian component of the Somalia COVID-19 CPRP launched in April is only 38 per cent funded, South West Mogadishu negatively impacting effective cluster responses. State Jubaland 14 State isolation units and one quarantine facility were Kismaayo supported during the "second wave" of COVID-19 pandemic Situation overview Confirmed cases by age and gender COVID-19 CASES ECONOMY AT RISK GROWTH CONTRACTION Source: MoH, WHO Over 4,662 confirmed According to the GDP growth estimated cases since 16 March, Heritage Institute of to contract to 2.5% in Age 83% 17% and 124 related deaths. -

History, External Influence and Political Volatility in the Central African Republic (CAR)

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Journal for the Advancement of Developing Economies Economics Department 2014 History, External Influence and oliticalP Volatility in the Central African Republic (CAR) Henry Kam Kah University of Buea, Cameroon Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/jade Part of the Econometrics Commons, Growth and Development Commons, International Economics Commons, Political Economy Commons, Public Economics Commons, and the Regional Economics Commons Kam Kah, Henry, "History, External Influence and oliticalP Volatility in the Central African Republic (CAR)" (2014). Journal for the Advancement of Developing Economies. 5. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/jade/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Economics Department at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal for the Advancement of Developing Economies by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Journal for the Advancement of Developing Economies 2014 Volume 3 Issue 1 ISSN:2161-8216 History, External Influence and Political Volatility in the Central African Republic (CAR) Henry Kam Kah University of Buea, Cameroon ABSTRACT This paper examines the complex involvement of neighbors and other states in the leadership or political crisis in the CAR through a content analysis. It further discusses the repercussions of this on the unity and leadership of the country. The CAR has, for a long time, been embroiled in a crisis that has impeded the unity of the country. It is a failed state in Africa to say the least, and the involvement of neighboring and other states in the crisis in one way or the other has compounded the multifarious problems of this country. -

Somalia and Somaliland: the Two Edged Sword of International Intervention Kenning, David

www.ssoar.info Somalia and Somaliland: the two edged sword of international intervention Kenning, David Veröffentlichungsversion / Published Version Zeitschriftenartikel / journal article Empfohlene Zitierung / Suggested Citation: Kenning, D. (2011). Somalia and Somaliland: the two edged sword of international intervention. Federal Governance, 8(2), 63-70. https://nbn-resolving.org/urn:nbn:de:0168-ssoar-342769 Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Dieser Text wird unter einer Basic Digital Peer Publishing-Lizenz This document is made available under a Basic Digital Peer zur Verfügung gestellt. Nähere Auskünfte zu den DiPP-Lizenzen Publishing Licence. For more Information see: finden Sie hier: http://www.dipp.nrw.de/lizenzen/dppl/service/dppl/ http://www.dipp.nrw.de/lizenzen/dppl/service/dppl/ Special Issue on Federalism and Conflict Management edited by Neophytos Loizides, Iosif Kovras and Kathleen Ireton. SOMALIA AND SOMALILAND: THE TWO EDGED SWORD OF INTERNATIONAL INTERVENTION by David Kenning* * Queen’s University Belfast, Ireland Email: [email protected] Abstract: Since the collapse of the state in Somalia in 1991 the country has been the recipient of numerous international interventions and operations but has not as yet reached a sustainable peaceful settlement, despite at one point costing the UN almost two billion dollars a year in its operations. In contrast Somaliland, the area that seceded in the north, despite not being recognised by international governments and having been on the brink of several civil wars, has reached a level of political reconciliation and economic growth that compares favourably to the rest of Somalia. This article argues that the international actors’ misinterpretation of Somali social and political organisation during intervention, Somaliland’s ability to engage in a form of democracy that is based on traditional politics and the different experience the area had during colonialism has meant that its society has reached an unlikely level of peace and reconciliation. -

Durable Solutions Framework

BENADIR REGION SOMALIA MARCH 2017 LOCAL INTEGRATION FOCUS: BENADIR REGION DURABLE SOLUTIONS FRAMEWORK Review of existing data and assessments to identify gaps and opportunities to inform (re)integration planning and programing for displacement affected communities Durable Solutions Framework - Local Integration Focus: Benadir region 2017 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This study could not have been completed without the help of many people. ReDSS gratefully acknowledges the support of the DSRSG/HC/RC office for organizing the consultations in Mogadishu with local authorities and representatives of civil society and for facilitating the validation process with the Durable Solution working group. ReDSS would also like to thank representatives of governments, UN agencies, clusters, NGOs, donors, and displacement affected communities for engaging in this process by sharing their knowledge and expertise and reviewing findings and recommendations at different stages. Without their involvement, it would not have been possible to complete this analysis. ReDSS would also like to express its gratitude to DFID and DANIDA for their financial support and to Ivanoe Fugali for conducting the research and writing this report. ABOUT the Regional Durable Solutions Secretariat (ReDSS) The search for durable solutions to the protracted displacement situation in East and Horn of Africa is a key humanitarian and development concern. This is a regional/cross border issue, dynamic and with a strong political dimension which demands a multi-sectorial response that goes beyond the existing humanitarian agenda. The Regional Durable Solutions Secretariat (ReDSS) was created in March 2014 with the aim of maintaining a focused momentum and stakeholder engagement towards durable solutions for displacement affected communities. The secretariat was established following extensive consultations among NGOs in the region, identifying a wish and a vision to establish a body that can assist stakeholders in addressing durable solutions more consistently. -

Somalia Complex Emergency Fact Sheet #1- 04-26-2013

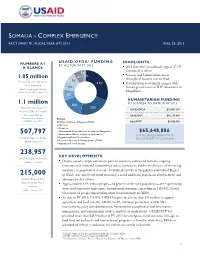

SOMALIA - COMPLEX EMERGENCY FACT SHEET #1, FISCAL YEAR (FY) 2013 APRIL 26, 2013 USAID/OFDA 1 F U N D I N G NUMBERS AT HIGHLIGHTS BY SECTOR IN FY 2013 A GLANCE 2013 Somalia Consolidated Appeal (CAP) requests $1.3 billion 2% Security and humanitarian access 6% 1% 1.05 million throughout Somalia remain fluid 7% People Experiencing Acute 31% Humanitarian community engages with Food Insecurity 7% Somali government on IDP relocations in U.N. Food Security and Nutrition Analysis Unit (FSNAU) – April 2013 Mogadishu 8% HUMANITARIAN FUNDING 1.1 million TO SOMALIA TO DATE IN FY 2013 15% Total Internally Displaced 23% USAID/OFDA $15,069,387 Persons (IDPs) in Somalia Office of the U.N. High USAID/FFP2 $45,579,499 Commissioner for Refugees Health 3 (UNHCR) – April 2013 Water, Sanitation, & Hygiene (WASH) State/PRM $5,000,000 Nutrition Protection Humanitarian Coordination & Information Management $65,648,886 507,797 Humanitarian Studies, Analysis, or Applications TOTAL USAID AND STATE Somali Refugees in Kenya Logistics and Relief Commodities ASSISTANCE TO SOMALIA Economic Recovery & Market Systems (ERMS) UNHCR – April 2013 Agriculture & Food Security 238,957 KEY DEVELOPMENTS Somali Refugees in Ethiopia UNHCR – April 2013 Despite security improvements in parts of southern and central Somalia, ongoing insecurity and restricted humanitarian access continue to hinder the delivery of life-saving assistance to populations in need. Al-Shabaab activity in Mogadishu and Bakool Region 215,000 in March and April heightened insecurity, caused additional population displacement, and Acutely Malnourished obstructed relief efforts. Children under Five in Approximately 1.05 million people—14 percent of the total population—are experiencing Somalia FSNAU – February 2013 acute food insecurity and require humanitarian assistance, according to FSNAU. -

Somalia - United States Department of State

Somalia - United States Department of State https://www.state.gov/reports/2020-trafficking-in-persons-report/somalia/ Somalia remains a Special Case for the 18th consecutive year. The country continued to face protracted conflict, insecurity, and ongoing humanitarian crises during the reporting period. The Federal Government of Somalia (FGS) controlled its capital city, Mogadishu, and Federal Member State (FMS) governments retained control over most local capitals across the country. The self-declared independent region of Somaliland and the Puntland FMS retained control of security and law enforcement in their respective regions. The FGS had limited influence outside Mogadishu. The al-Shabaab terrorist group continued to occupy and control rural areas and maintained operational freedom of movement in many other areas in south-central Somalia, which it used as a base to exploit the local population by collecting illegal taxes, conducting indiscriminate attacks against civilian and civilian infrastructure across the country, and perpetrating human trafficking. The FGS focused on capacity building and securing Mogadishu and government facilities from attacks by al-Shabaab. The sustained insurgency by al-Shabaab continued to be the main obstacle to the government’s ability to address human trafficking. The government continued to modestly improve capacity to address most crimes; however, it demonstrated minimal efforts in all regions on prosecution, protection, and prevention of trafficking during the reporting year. The FGS, Somaliland, and Puntland authorities sustained minimal efforts to combat trafficking during the reporting period. Due to the protracted campaign to degrade al-Shabaab and establish law and order in Somalia, law enforcement, prosecutorial personnel, and judicial offices remained understaffed, undertrained, and lacked capacity to effectively enforce anti-trafficking laws. -

Exploring the Old Stone Town of Mogadishu

Exploring the Old Stone Town of Mogadishu Exploring the Old Stone Town of Mogadishu By Nuredin Hagi Scikei Exploring the Old Stone Town of Mogadishu By Nuredin Hagi Scikei This book first published 2017 Cambridge Scholars Publishing Lady Stephenson Library, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2PA, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2017 by Nuredin Hagi Scikei All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-5275-0331-3 ISBN (13): 978-1-5275-0331-1 Dedicated to my father Hagi Scikei Abati, my mother Khadija Ali Omar, my sister Zuhra and my brother Sirajadin. CONTENTS Preface ........................................................................................................ xi Acknowledgements .................................................................................. xiii Chapter One ................................................................................................. 1 Introduction Who are the Banaadiri Maritime Traders and Ancient Banaadiri Settlements Religion and Learning The Growth of Foreign Trade, Urbanisation and the First Industries of Banaadir Chapter Two .............................................................................................. 11 The Campaign of Defamation against the Banaadiri -

(I) the SOCIAL STRUCTUBE of Soumn SOMALI TRIB by Virginia I?

(i) THE SOCIAL STRUCTUBE OF SOumN SOMALI TRIB by Virginia I?lling A thesis submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy at the University of London. October 197]. (ii) SDMMARY The subject is the social structure of a southern Somali community of about six thousand people, the Geledi, in the pre-colonial period; and. the manner in which it has reacted to colonial and other modern influences. Part A deals with the pre-colonial situation. Section 1 deals with the historical background up to the nineteenth century, first giving the general geographic and ethnographic setting, to show what elements went to the making of this community, and then giving the Geledj's own account of their history and movement up to that time. Section 2 deals with the structure of the society during the nineteenth century. Successive chapters deal with the basic units and categories into which this community divided both itself and the others with which it was in contact; with their material culture; with economic life; with slavery, which is shown to have been at the foundation of the social order; with the political and legal structure; and with the conduct of war. The chapter on the examines the politico-religious office of the Sheikh or Sultan as the focal point of the community, and how under successive occupants of this position, the Geledi became the dominant power in this part of Somalia. Part B deals with colonial and post-colonial influences. After an outline of the history of Somalia since 1889, with special reference to Geledi, the changes in society brought about by those events are (iii) described. -

Trees of Somalia

Trees of Somalia A Field Guide for Development Workers Desmond Mahony Oxfam Research Paper 3 Oxfam (UK and Ireland) © Oxfam (UK and Ireland) 1990 First published 1990 Revised 1991 Reprinted 1994 A catalogue record for this publication is available from the British Library ISBN 0 85598 109 1 Published by Oxfam (UK and Ireland), 274 Banbury Road, Oxford 0X2 7DZ, UK, in conjunction with the Henry Doubleday Research Association, Ryton-on-Dunsmore, Coventry CV8 3LG, UK Typeset by DTP Solutions, Bullingdon Road, Oxford Printed on environment-friendly paper by Oxfam Print Unit This book converted to digital file in 2010 Contents Acknowledgements IV Introduction Chapter 1. Names, Climatic zones and uses 3 Chapter 2. Tree descriptions 11 Chapter 3. References 189 Chapter 4. Appendix 191 Tables Table 1. Botanical tree names 3 Table 2. Somali tree names 4 Table 3. Somali tree names with regional v< 5 Table 4. Climatic zones 7 Table 5. Trees in order of drought tolerance 8 Table 6. Tree uses 9 Figures Figure 1. Climatic zones (based on altitude a Figure 2. Somali road and settlement map Vll IV Acknowledgements The author would like to acknowledge the assistance provided by the following organisations and individuals: Oxfam UK for funding me to compile these notes; the Henry Doubleday Research Association (UK) for funding the publication costs; the UK ODA forestry personnel for their encouragement and advice; Peter Kuchar and Richard Holt of NRA CRDP of Somalia for encouragement and essential information; Dr Wickens and staff of SEPESAL at Kew Gardens for information, advice and assistance; staff at Kew Herbarium, especially Gwilym Lewis, for practical advice on drawing, and Jan Gillet for his knowledge of Kew*s Botanical Collections and Somalian flora.