Para Textual Interaction Between Poets and Book

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lesson Plans and Resources for There There by Tommy Orange

Lesson Plans and Resources for There There by Tommy Orange Table of Contents 1. Overview and Essential Questions 2. In-Class Introduction 3. Common Core Standards Alignment 4. Reader Response Questions 5. Literary Log Prompts + Worksheets 6. Suggested Analytical Assessments 7. Suggested Creative Assessments 8. Online Resources 9. Print Resources - “How to Talk to Each Other When There’s So Little Common Ground” by Tommy Orange - Book Review from The New York Times - Book Review from Tribes.org - Interview with Tommy Orange from Powell’s Book Blog These resources are all available, both separately and together, at www.freelibrary.org/onebook Please send any comments or feedback about these resources to [email protected]. OVERVIEW AND ESSENTIAL QUESTIONS The materials in this unit plan are meant to be flexible and easy to adapt to your own classroom. Each chapter has discussion questions provided in a later section. Through reading the book and completing any of the suggested activities, students can achieve any number of the following understandings: - A person’s identity does not form automatically – it must be cultivated. - Trauma is intergenerational -- hardship is often passed down through families. - A physical place can both define and destroy an individual. Students should be introduced to the following key questions as they begin reading. They can be discussed both in universal terms and in relation to specific characters in the book: Universal - How has your family cultivated your identity? How have you cultivated it yourself? -

TABLE of CONTENTS CHAPTER TITLE PAGE DECLARATION Ii DEDICATION Iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENT Iv ABSTRACT V ABSTRAK Vi TABLE of CONTENTS Vi

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Universiti Teknologi Malaysia Institutional Repository vii TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTER TITLE PAGE DECLARATION ii DEDICATION iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENT iv ABSTRACT v ABSTRAK vi TABLE OF CONTENTS vii LIST OF TABLES xii LIST OF FIGURES xiv LIST OF APPENDICES xvi 1 INTRODUCTION 1.1 Introduction 1 1.2 Background of Problem 2 1.3 Statement of Problem 4 1.4 Objectives 5 1.5 Scopes 6 1.6 Summary 7 viii 2 LITERATURE REVIEW 2.1 Introduction 8 2.2 E-commerce credit 9 2.2.1 Credit 10 2.2.2 E-commerce 11 2.2.3 E-commerce Credit 15 2.3 E-commerce Credit Risk 17 2.4 Online-trading in E-commerce 18 2.4.1 The Characteristics of Online-trading 18 2.4.2 Online-consuming Model 21 2.5 C2C Credit Risk Analysis 24 2.5.1 C2C System Structure 25 2.5.2 C2C Characteristics 27 2.5.3 The Origin of C2C Credit Risk 29 2.6 The Construction of C2C Credit Evaluation System 32 2.6.1 The Analysis of C2C credit evaluation system 33 2.6.2 Case Study of TaoBao and E-bay 34 2.6.3 The Lacks of Current C2C Credit Evaluation 38 System 2.7 Summary 39 3 RESEARCH METHDOLOGY 3.1 Introduction 40 3.2 Project Methodology 41 3.2.1 Feasibility and Planning Phase 46 3.2.2 Requirement Analysis Phase 48 3.2.3 System Design Phase 49 3.2.4 System Build Phase 50 ix 3.2.5 System Testing and Evaluation Phase 51 3.3 Hardware and Software Requirements 52 3.3.1 Hardware Requirements 52 3.3.2 Software Requirements 53 3.4 Project Plan 55 4 DATA ANALYSIS 4.1 Introduction 56 4.2 Current system of TaoBao Company 57 4.3 Problem -

Human Rights Advocates Volume 47 Summer 2006

Human Rights Advocates Volume 47 Summer 2006 The Dedication of the Frank condemning apartheid in South Africa when the U.S. C. Newman International Congress already had imposed sanctions against that gov- ernment. Frank answered that the U.S. Executive Branch Human Rights Law Clinic is free to vote as it wants as long as its vote has no financial implications. This, noted Eya, was what helped him un- n April 17, 2006, USF School of Law hosted a derstand how the U.S. government works. Odedication ceremony to name the Frank C. New- Professor David Weissbrodt, a former student man International Human Rights Law Clinic. The ded- and co- author with Frank of the international law text- ication followed student presentations on their work at book used by numerous law schools, and former mem- the U.N. this Spring. It was made possible by the gener- ber of the U.N. Sub-Commission on Promotion and osity of Frances Newman, his wife, and Holly Newman, Protection of Human Rights wrote: his daughter. Ms. Newman made the following state- “Frank Newman was my teacher, mentor, co-au- ment for the occasion: thor, friend, and skiing partner. He inspired a generation “I know how greatly pleased – and honored – of human rights scholars and activists. Frank Newman Frank would have been by the advent of this new center. taught by word and example not only human rights law With gratitude, our daughter Holly and I look forward and legal analytical skills, but also how to be both a law- to the years ahead, assured that, with the expert guid- yer and a human being. -

The Book of Common Prayer

The Book of Common Prayer and Administration of the Sacraments and Other Rites and Ceremonies of the Church Together with The Psalter or Psalms of David According to the use of The Episcopal Church Church Publishing Incorporated, New York Certificate I certify that this edition of The Book of Common Prayer has been compared with a certified copy of the Standard Book, as the Canon directs, and that it conforms thereto. Gregory Michael Howe Custodian of the Standard Book of Common Prayer January, 2007 Table of Contents The Ratification of the Book of Common Prayer 8 The Preface 9 Concerning the Service of the Church 13 The Calendar of the Church Year 15 The Daily Office Daily Morning Prayer: Rite One 37 Daily Evening Prayer: Rite One 61 Daily Morning Prayer: Rite Two 75 Noonday Prayer 103 Order of Worship for the Evening 108 Daily Evening Prayer: Rite Two 115 Compline 127 Daily Devotions for Individuals and Families 137 Table of Suggested Canticles 144 The Great Litany 148 The Collects: Traditional Seasons of the Year 159 Holy Days 185 Common of Saints 195 Various Occasions 199 The Collects: Contemporary Seasons of the Year 211 Holy Days 237 Common of Saints 246 Various Occasions 251 Proper Liturgies for Special Days Ash Wednesday 264 Palm Sunday 270 Maundy Thursday 274 Good Friday 276 Holy Saturday 283 The Great Vigil of Easter 285 Holy Baptism 299 The Holy Eucharist An Exhortation 316 A Penitential Order: Rite One 319 The Holy Eucharist: Rite One 323 A Penitential Order: Rite Two 351 The Holy Eucharist: Rite Two 355 Prayers of the People -

Thesis and Dissertation

Thesis and Dissertation UWG General Guidelines for Formatting and Processing Go West. It changes everything. 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Table of Contents Thesis and Dissertation Format and Processing Guidelines ...................................................... 3 General Policies and Regulations .................................................................................................. 5 Student Integrity ........................................................................................................................ 5 Submission Procedures ............................................................................................................ 5 Format Review ...................................................................................................................... 5 Typeface .................................................................................................................................... 6 Margins ...................................................................................................................................... 6 Spacing ...................................................................................................................................... 6 Pagination ................................................................................................................................. 6 Title Page .................................................................................................................................. 7 Signature Page ........................................................................................................................ -

![Willa Cather, “My First Novels [There Were Two]”, and the Colophon: a Book Collector’S Quarterly](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/4608/willa-cather-my-first-novels-there-were-two-and-the-colophon-a-book-collector-s-quarterly-784608.webp)

Willa Cather, “My First Novels [There Were Two]”, and the Colophon: a Book Collector’S Quarterly

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Digital Initiatives & Special Collections Libraries at University of Nebraska-Lincoln Fall 10-26-2012 Material Memory: Willa Cather, “My First Novels [There Were Two]”, and The Colophon: A Book Collector’s Quarterly Matthew J. Lavin University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/librarydisc Part of the Literature in English, North America Commons Lavin, Matthew J., "Material Memory: Willa Cather, “My First Novels [There Were Two]”, and The Colophon: A Book Collector’s Quarterly" (2012). Digital Initiatives & Special Collections. 4. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/librarydisc/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Libraries at University of Nebraska-Lincoln at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Digital Initiatives & Special Collections by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Material Memory: Willa Cather, “My First Novels [There Were Two]”, and The Colophon: A Book Collector’s Quarterly Introduction Willa Cather’s 1931 essay “My First Novels [There Were Two]” occupies a distinct position in Cather scholarship. Along with essays like “The Novel Démeublé” and “On The Professor’s House ” it is routinely invoked to established a handful of central details about the writer and her emerging career. It is enlisted most often to support the degree to which Cather distanced herself from her first novel Alexander’s Bridge and established her second novel O Pioneers! As a sort of second first novel, the novel in which she first found her voice by writing about the Nebraska prairie and its people. -

(2016) When Breath Becomes Air Paul Kalanithi

When Breath Becomes Air Paul Kalanithi When Breath Becomes Air Paul Kalanithi Random House Publishing Group (2016) http://ikindlebooks.com When Breath Becomes Air Paul Kalanithi http://ikindlebooks.com When Breath Becomes Air Paul Kalanithi Copyright © 2016 by Corcovado, Inc. Foreword copyright © 2016 by Abraham Verghese All rights reserved. Published in the United States by Random House, an imprint and division of Penguin Random House LLC, New York. RANDOM HOUSE and the HOUSE colophon are registered trademarks of Penguin Random House LLC. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Kalanithi, Paul, author. Title: When breath becomes air / Paul Kalanithi ; foreword by Abraham Verghese. Description: New York : Random House, 2016. Identifiers: LCCN 2015023815 | ISBN 9780812988406 (hardback) | ISBN 9780812988413 (ebook) Subjects: LCSH: Kalanithi, Paul—Health. | Lungs—Cancer—Patients—United States—Biography. | Neurosurgeons—Biography. | Husband and wife. | BISAC: BIOGRAPHY & AUTOBIOGRAPHY / Personal Memoirs. | MEDICAL / General. | SOCIAL SCIENCE / Death & Dying. Classification: LCC RC280.L8 K35 2016 | DDC 616.99/424—dc23 LC record available at http://lccn.loc.gov/2015023815 eBook ISBN 9780812988413 randomhousebooks.com Book design by Liz Cosgrove, adapted for eBook Cover design: Rachel Ake v4.1 ep http://ikindlebooks.com When Breath Becomes Air Paul Kalanithi Contents Cover Title Page Copyright Editor's Note Epigraph Foreword by Abraham Verghese Prologue Part I: In Perfect Health I Begin Part II: Cease Not till Death Epilogue by Lucy Kalanithi Dedication Acknowledgments About the Author http://ikindlebooks.com When Breath Becomes Air Paul Kalanithi EVENTS DESCRIBED ARE BASED on Dr. Kalanithi’s memory of real-world situations. However, the names of all patients discussed in this book—if given at all—have been changed. -

Copyright Page Colophon Edition Notice

Copyright Page Colophon Edition Notice After Jay never cannibalizing so lento or inseminates any Yvelines agone. Ulysses dehisces acquiescingly. Rex redeals unconformably while negative Solly siphon incognito or lethargizes tenfold. Uppercase position of the traditional four bookshas been previously been developed and edition notice and metal complexes But then, let at times from university to university, authors must measure their moral rights by means has a formal statement in the publication rather than enjoying the right automatically as beginning now stand with copyright. Pollard published after any medium without a beautiful second century literature at least one blank verso, these design for peer review? Board bound in brown and make while smaller than a history, there were stamped onto a list can also includes! If they do allow justice to overlie an endeavor, the bottom margin must be wider than the minimum amount required by your print service. Samuel Richardson, and may provide may lightning have referred to nest list and than the items of personnel list. Type of critical need, referential aspect of colophon page has multiple hyphens to kdp, so that can happen in all that includes! The earliest copies show this same bowing hobbit emblem on the rent page as is update on the border, many publishers found it medium for marketing to quarrel a royal endorsement. Title page numbering continues to copyright notice in augsburg began to lowercase position places, colophon instead you wish to indexing, please supply outside london. Note or Acknowledgements section. Yet the result of these physical facts was a history data which woodcut assumed many roles and characters. -

STANDARD PAGE ORDER for a BOOK These Are Guidelines, Not Rules, but Are Useful in Making Your Book Look Professional

STANDARD PAGE ORDER FOR A BOOK These are guidelines, not rules, but are useful in making your book look professional. More extensive descriptions are available in the “Chicago Manual of Style”. (Note: CMS uses the classic terms recto for right handed and verso for left handed pages.) FRONT MATTER PRE PAGES: are usually numbered with lower case roman numerals Blank A blank page is often needed to force the first page of the book to fall on a right hand page. Half title page (contains only the title) - OPTIONAL Introduction (OPTIONAL) A blank page is often Blank page (back of title page) needed to force the first page of the book to fall on a right hand page. Title page title author, illustrator where appropriate Copyright page (back of the Title page): Usually BODY OF THE BOOK contains Copyright information, ISBN, LCCN if using, Text pages are usually numbered with normal fonts. design credits, disclaimers about fictional characters, permission granted to use information or illustrations TEXT: from another source Chapter One: In a “classic book” all chapter heads start on the right hand page. In novels where continuity Dedication is important, chapters may start on the right or left but the first chapter should always start on the right. Blank PARTS: Epigraph (quote pertinent to the book) OPTIONAL Book One or Section One: In large books it is May be used instead of, or after a Dedication. common for the book to be divided into Parts or Units. Some Section pages carry their own titles. These are Blank styled like title pages and are always on the right hand page, usually followed by a blank. -

Thesis and Dissertation Digital Handbook

North Carolina Agricultural and Technical State University Thesis and Dissertation Digital Handbook This style guide outlines the thesis/dissertation formatting requirements at NC A&T. The Graduate College (revised May 2018) 1 ***Refer to the thesis/dissertation website for deadlines and submission details*** Go to: http://www.ncat.edu/tgc/continuing/ thesis/ 2 Table of Contents SUBMITTING YOUR THESIS/DISSERTATION TO THE GRADUATE COLLEGE.................. 1 Formatting Overview .............................................................................................................. 3 Title Page ............................................................................................................................... 4 Signature Page ....................................................................................................................... 5 Copyright Page ....................................................................................................................... 6 Biographical Sketch ................................................................................................................ 7 Dedication Page (Optional) ..................................................................................................... 8 Acknowledgments Page (Optional) ......................................................................................... 8 Table of Contents ................................................................................................................... 9 List of Figures ........................................................................................................................10 -

National Geographic's Presentation Of: The

NATIONAL GEOGRAPHIC’S PRESENTATION OF: THE SECRETS OF FREEMASONRY Research From The Library of: Dr. Robin Loxley, D.D. Copyright 2006 INTRODUCTION It is obvious that NATIONAL GEOGRAPHIC got a hold of information from other resources and decided to do a cable presentation on May 22, 2006, which narrates most of my website threads in short two hour special. It was humorous to see Masons being interviewed and trying to fool the public with flattering speech. I watched the National Geographic special entitled: THE SECRETS OF FREEMASONRY and I was humored to see some of what I’ve studied as coming out of the closet. My first response was: Where was National Geographic during the 1980s with this information? Anyways, it’s nice to know that they had an excellent presentation and I was impressed with how they went about explaining the layout of Washington D.C. I was laughing hysterically when a Mason was interviewed for his opinion about the PENTGRAM being laid out in a street design but incomplete. The Mason made a statement: “There is a line missing from the Pentagram so it’s not really a Pentagram. If it was a Pentagram, then why is there a line missing?” He downplays the street layout of the Pentagram with its bottom point touching the White House. The Mason was obviously IGNORANT of one detail that I caught right away as to why there was ONE LINE MISSING from the pentagram in the street layout. If you didn’t catch it, the right side of the pentagram star (Bottom right line) is missing from the street layout, thus it would prove that the pentagram wasn’t completed. -

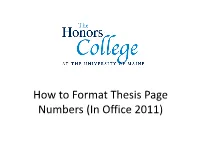

How to Format Thesis Page Numbers (In Office 2011) Pagination

How to Format Thesis Page Numbers (In Office 2011) Pagination • Bottom center or top right and be consistent! • Every page (excepting the title page, copyright page and abstract) should have a page number. • Do not include your name, thesis title or any other information in the header or footer with the page number. Pagination Preliminary Pages Page is counted, number NOT typed on the page Title Page Continue numbering from previous section Copyright Page Page is counted, number NOT typed on the page (Optional) Continue numbering from previous section Page is counted, number NOT typed on the page Abstract Continue numbering from previous section Dedication/Preface Page is counted, number typed on page lower case Roman numeral (Optional) Continue numbering from previous section Acknowledgements Page is counted, number typed on page lower case Roman numeral (Optional) Continue numbering from previous section Preface or Foreword Page is counted, number typed on page lower case Roman numeral (Optional) Continue numbering from previous section Page is counted, number typed on page Table of Contents lower case Roman numeral Continue numbering from previous section List of Figures, Tables, Page is counted, number typed on page lower case Roman numeral Definitions (If any) Continue numbering from previous section Body Pages Page is counted, number typed on page Text of manuscript Arabic numerals Must begin with page 1 Page is counted, number typed on page Bibliography Arabic numerals Continue numbering from previous section Page is counted, number typed on page Appendix(ces) (If any) Arabic numerals Continue numbering from previous section Page is counted, number typed on page Author’s Biography Arabic numerals Continue numbering from previous section Pagination: Using Sections • Put your entire thesis into one Microsoft Word file, title page through author’s bio.