Report Volume VI the State of the World’S Sea Turtles the the Most Valuable Reptile in the World Green Turtle

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Atoll Research Bulletin

ATOLL RESEARCH BULLETIN NO. 195. CORAL CAYS OF THE CAPRICORN AND BUNKER GROUPS, GREAT BARRIER REEF PROVINCE, AUSTRALIA by P. G. Flood Issued by THE SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION Washington, D.C., U.S.A. February 1977 Fig. 1. Location of the Capricorn and Bunker Groups. Atoll Research Bulletin No. 195. Flood, P.G.Feb. 1977 CORAL CAYS OF THE CAPRICORN AND BUNKER GROUPS, GREAT BARRIER KEEP PROVINCE, AUSTRALIA by P.G. Flood Introduction The islands and reefs of the Capricorn and Bunker Groups.are situated astride the Tropic of Capricorn at the southern end of the Great Barrier Reef Province and approximately 80 kilometres east of Gladstone which is situated on the central coast of Queensland (Fig. 1). The Capricorn Group of islands consists of nine coral cays: North Island, Tryon Island, North West Island, Wi.lson Island, Wreck Island, Masthead Island, Heron Island, and One Tree Island. A tourist Resort and Marine Scientific Research Station have been established on Heron Island. A manned lighthouse operates at North Island and the Australian Museum conducts a field research station on One Tree Island. The Bunker Group consists of five coral cays: Lady Musgrave Island, Fairfax Islands (West and East), and Hoskyn Islands (West and East). Morphological changes occurring between 1936 and 1973 are evident when comparing previous plans of these coral cays (Steers, 1938) with recent vertical aerial photographs. Changes are catagorised into two groups; those related to natural phenomena and secondly, those caused by human interference. Previous work The earliest scientific description of the Capricorn and Bunker Groups is that of Jukes (1847) who visited the area in 1843 on the voyage of H.M.S. -

Proceedings of the United States National Museum

Proceedings of the United States National Museum SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION • WASHINGTON, D.C. Volume 125 1968 Number 3666 Stomatopod Crustacea from West Pakistan By Nasima M. Tirmizi and Raymond B. Manning * Introduction As part of a broad program of studies on the larger Crustacea of West Pakistan and the Ai'abian Sea, one of us (N.T.) initiated a survey of the Stomatopoda occurring off the coast of West Pakistan. Analysis of preliminary collections indicated that the stomatopod fauna of this area is richer in numbers of species than is evident from the literature. Through correspondence in 1966, we decided to collaborate on a review of the Pakistani stomatopods; this report is the result of that collaboration. This paper is based prhnarily on collections made by and housed in the Zoology Department, University of Karachi. Specimens in the collections of the Central Fisheries Department, Karachi, and the Zoology Department, University of Sind, were also studied. Unfortu- nately, only a few specimens from the more extensive stomatopod collections of the Zoological Survey Department, Karachi, were available for study. Material from Pakistan in the collection of the Division of Crustacea, Smithsonian Institution (USNM), material from two stations made off Pakistan by the International Indian 1 Tirmizi: Reader, Zoology Department, University of Karachi, Pakistan; Manning, Chairman, Department of Invertebrate Zoology, Smithsonian Institu- tion. 2 PROCEEDINGS OF THE NATIONAL MUSEUM vol. 125 Ocean Expedition (IIOE), and a few specimens in the collections of the British Museum (Natural History) (BMNH), are also recorded. Some species of stomatopods are edible and are relished in various parts of the world. -

In the Northern Mariana Islands

THE TRADITIONAL AND CEREMONIAL USE OF THE GREEN TURTLE (Chelonia mydas) IN THE NORTHERN MARIANA ISLANDS with recommendations for ITS USE IN CULTURAL EVENTS AND EDUCATION A Report prepared for the Western Pacific Regional Fishery Management Council and the University of Hawaii Sea Grant College Program by Mike A. McCoy Kailua-Kona, Hawaii December, 1997 TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY...........................................................................................................................4 PREFACE......................................................................................................................................................8 1. INTRODUCTION....................................................................................................................................9 1.1 BACKGROUND ......................................................................................................................................9 1.2 TERMS OF REFERENCE AND METHODOLOGY ............................................................................10 1.3 DISCUSSION OF DEFINITIONS .........................................................................................................11 2. GREEN TURTLES, ISLANDS AND PEOPLE OF THE NORTHERN MARIANAS ...................12 2.1 SUMMARY OF GREEN TURTLE BIOLOGY.....................................................................................12 2.2 DESCRIPTION OF THE NORTHERN MARIANA ISLANDS ............................................................14 2.3 SOME RELEVANT -

Issue Number 118 October 2007 ISSN 0839-7708 in THIS

Issue Number 118 October 2007 Green turtle hatchling from Turkey with extra carapacial scutes (see pp. 6-8). Photo by O. Türkozan IN THIS ISSUE: Editorial: Conservation Conflicts, Conflicts of Interest, and Conflict Resolution: What Hopes for Marine Turtle Conservation?..........................................................................................L.M. Campbell Articles: From Hendrickson (1958) to Monroe & Limpus (1979) and Beyond: An Evaluation of the Turtle Barnacle Tubicinella cheloniae.........................................................A. Ross & M.G. Frick Nest relocation as a conservation strategy: looking from a different perspective...................O. Türkozan & C. Yılmaz Linking Micronesia and Southeast Asia: Palau Sea Turtle Satellite Tracking and Flipper Tag Returns......S. Klain et al. Morphometrics of the Green Turtle at the Atol das Rocas Marine Biological Reserve, Brazil...........A. Grossman et al. Notes: Epibionts of Olive Ridley Turtles Nesting at Playa Ceuta, Sinaloa, México...............................L. Angulo-Lozano et al. Self-Grooming by Loggerhead Turtles in Georgia, USA..........................................................M.G. Frick & G. McFall IUCN-MTSG Quarterly Report Announcements News & Legal Briefs Recent Publications Marine Turtle Newsletter No. 118, 2007 - Page 1 ISSN 0839-7708 Editors: Managing Editor: Lisa M. Campbell Matthew H. Godfrey Michael S. Coyne Nicholas School of the Environment NC Sea Turtle Project A321 LSRC, Box 90328 and Earth Sciences, Duke University NC Wildlife Resources Commission Nicholas School of the Environment 135 Duke Marine Lab Road 1507 Ann St. and Earth Sciences, Duke University Beaufort, NC 28516 USA Beaufort, NC 28516 USA Durham, NC 27708-0328 USA E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] Fax: +1 252-504-7648 Fax: +1 919 684-8741 Founding Editor: Nicholas Mrosovsky University of Toronto, Canada Editorial Board: Brendan J. -

The Geography and History of *R-Loss in Southern Oceanic Languages Alexandre François

Where *R they all? The Geography and History of *R-loss in Southern Oceanic Languages Alexandre François To cite this version: Alexandre François. Where *R they all? The Geography and History of *R-loss in Southern Oceanic Languages. Oceanic Linguistics, University of Hawai’i Press, 2011, 50 (1), pp.140 - 197. 10.1353/ol.2011.0009. hal-01137686 HAL Id: hal-01137686 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01137686 Submitted on 17 Oct 2016 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Where *R they all? The Geography and History of *R-loss in Southern Oceanic Languages Alexandre François LANGUES ET CIVILISATIONS À TRADITION ORALE (CNRS), PARIS, AND AUSTRALIAN NATIONAL UNIVERSITY Some twenty years ago, Paul Geraghty offered a large-scale survey of the retention and loss of Proto-Oceanic *R across Eastern Oceanic languages, and concluded that *R was “lost in proportion to distance from Western Oceanic.” This paper aims at testing Geraghty’s hypothesis based on a larger body of data now available, with a primary focus on a tightly knit set of languages spoken in Vanuatu. By observing the dialectology of individual lexical items in this region, I show that the boundaries between languages retaining vs. -

D.T. Potts (Sydney) Introduction Although None of the Achaemenid Royal Inscriptions Listing the Satrapies (Junge 1942; Lecoq

THE ISLANDS OF THE XIVTH SATRAPY D.T. Potts (Sydney) Introduction Although none of the Achaemenid royal inscriptions listing the satrapies (Junge 1942; Lecoq 1997) under Darius (DB §6; DNa §3; DNe, DPe §2; Dse §3; DSm §2; DSaa §4; the incomplete DSv §2), Xerxes (XPh §3) or Artaxerxes II (A2Pa) refer to them, the islands of the Erythraean Sea appear in two important Greek sources. 1. In Book 3, where the famous ‘Steuerliste’, believed by many to reflect Darius I’s satrapal reforms (Hist. 3.89), appears, Herodotus says: ‘The fourteenth province consisted of the Sagartians, Sarangians, Thamanaeans, Utians, Mycians and the inhabitants of the islands in the Erythraean Sea where the Persian king settles the people known as the dispossessed, who together contributed 600 talents’ (Hist. 3.93). 2. In Book 4 Herodotus writes, ‘Persians live all the way south as far as the sea which is called the Erythraean Sea’ (Hist. 4.37). 3. In Book 7 Herodotus describes the infantry contingents which fought for Xerxes at Doriscus. He says: ‘The tribes who had come from the islands in the Erythraean Sea to take part in the expedition - the islands where the Persian king settles the peoples known as the ‘dispossessed’ - closely resembled the Medes in respect of both clothing and weaponry. These islanders were commanded by Mardontes the son of Bagaeus1, who was one of the Persian commanders a year later at the battle of Mycale, where he died’(Hist. 7.80). 4. Finally, in Arrian’s (Anab. Alex. 3.8.5) description of the forces of Darius III at Issus, we read, ‘The tribes bordering on the Erythraean Sea were directed by Orontobates, Ariobarzanes and Orxines’. -

Race War Draft 2

Race War Comics and Yellow Peril during WW2 White America’s fear of Asia takes the form of an octopus… The United States Marines #3 (1944) Or else a claw… Silver Streak Comics #6 (Sept. 1940)1 1Silver Streak #6 is the first appearance of Daredevil Creatures whose purpose is to reach out and ensnare. Before the Octopus became a symbol of racial fear it was often used in satirical cartoons to stoke a fear of hegemony… Frank Bellew’s illustration here from 1873 shows the tentacles of the railroad monopoly (built on the underpaid labor of Chinese immigrants) ensnaring our dear Columbia as she struggles to defend the constitution from such a beast. The Threat is clear, the railroad monopoly is threating our national sovereignty. But wait… Isn’t that the same Columbia who the year before… Yep… Maybe instead of Columbia frightening away Indigenous Americans as she expands west, John Gast should have painted an octopus reaching out across the continent grabbing land away from them. White America’s relationship with hegemony has always been hypocritical… When White America views the immigration of Chinese laborers to California as inevitably leading to the eradication of “native” White Americans, it can only be because when White Americans themselves migrated to California they brought with them an agenda of eradication. In this way White European and American “Yellow Peril” has largely been based on the view that China, Japan, and India represent the only real threats to white colonial dominance. The paranoia of a potential competitor in the game of rule-the-world, especially a competitor perceived as being part of a different species of humans, can be seen in the motivation behind many of the U.S.A.’s military involvement in Asia. -

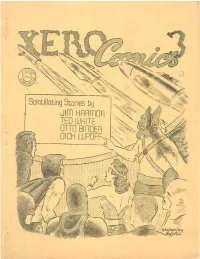

Xero Comics 3

[A/katic/Po about Wkatto L^o about ltdkomp5on,C?ou.l5on% ^okfy Madn.^5 and klollot.-........ - /dike U^eckin^z 6 ^Tion-t tke <dk<dfa............. JlaVuj M,4daVLi5 to Tke -dfec'iet o/ (2apta Ln Video ~ . U 1 _____ QilkwAMyn n 2t £L ......conducted byddit J—upo 40 Q-b iolute Keto.................. ............Vldcjdupo^ 48 Q-li: dVyL/ia Wklie.... ddkob dVtewait.... XERO continues to appall an already reeling fandom at the behest of Pat & Dick Lupoff, 21J E 7Jrd Street, New York 21, New York. Do you want to be appalled? Conies are available for contributions, trades, or letters of comment. No sales, no subs. No, Virginia, the title was not changed. mimeo by QWERTYUIOPress, as usual. A few comments about lay ^eam's article which may or lay not be helpful. I've had similar.experiences with readers joining fan clubs. Tiile at Penn State, I was president of the 3F‘Society there, founded by James F. Cooper Jr, and continued by me after he gafiated. The first meeting held each year packed them in’ the first meeting of all brought in 50 people,enough to get us our charter from the University. No subsequent meeting ever brought in more than half that, except when we held an auction. Of those people, I could count on maybe five people to show up regularly, meet ing after meeting, just to sit and talk. If we got a program together, we could double or triple that. One of the most popular was the program vzhen we invited a Naval ROTO captain to talk about atomic submarines and their place in future wars, using Frank Herbert's novel Dragon in the ~ea (or Under Pressure or 21 st Century Sub, depending upon where you read itj as a starting point. -

Report of the Sixth Inter-Governmental Meeting of Ministers of South Asian Seas Programme

SOUTH ASIA CO-OPERATIVE ENVIRONMENT PROGRAMME SOUTH ASIAN SEAS PROGRAMME SOUTH ASIAN SEAS PROGRAMME 6th Inter-governmental Meeting of Ministers Dhaka, Bangladesh 5 – 6 November 2019 REPORT OF THE SIXTH INTER-GOVERNMENTAL MEETING OF MINISTERS OF SOUTH ASIAN SEAS PROGRAMME Report of the 6th Inter-governmental Meeting of Ministers South Asian Seas Programme 5 – 6 November 2019, Dhaka, Bangladesh South Asia Co-operative Environlll.ent Progralll.lIl.e South Asian Seas Progralll.lIl.e No . 146j24A, Havelock Road, Colombo 5, Sri Lanka CERTIFICATE The Report of the Sixth Inter-governmental Meeting of Ministers of the South Asian Seas Programme held on 5 - 6 November 2019 in Dhaka, Bangladesh is herewith submitted to the members of the Inter governmental Meeting of Ministers and the Consultative Committee, in fulfliment of the fmancial and administrative procedures of SACEP and SASP. c::=w~~------~~;r~IT Director General 30th January 2020 (iii) Report of the 6/1' Illter-govenmlelltal Meetillg ofMillisters SOllth Asiml Seas Programme 5 - 6 November 2019, Dhaka, Ballgladesh Report of the 6th Inter-governmental Meeting of Ministers South Asian Seas Programme 5 – 6 November 2019, Dhaka, Bangladesh Report of the Sixth Inter-governmental Meeting of Ministers of South Asian Seas Programme (SASP) 5 – 6 November 2019 Dhaka, Bangladesh Report of the 6th Inter-governmental Meeting of Ministers South Asian Seas Programme 5 – 6 November 2019, Dhaka, Bangladesh Report of the 6th Inter-governmental Meeting of Ministers South Asian Seas Programme 5 – 6 November 2019, Dhaka, Bangladesh REPORT OF THE SIXTH INTER-GOVERNMENTAL MEETING OF MINISTERS OF THE SOUTH ASIAN SEAS PROGRAMME Para No. -

Honeymoon NOT YOUR VALE

Not Your Valentine by Joyce Magnin Illustrations by Christina Weidman Created by Mark Andrew Poe I'd rather eat spiders than dance. — Honey Moon Not Your Valentine (Honey Moon) By Joyce Magnin Created by Mark Andrew Poe © Copyright 2018 by Mark Andrew Poe. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any written, electronic recording, or photocopying without written permission of the publisher, except for brief quotations in articles, reviews or pages where permission is specifically granted by the publisher. "The Walt Disney Studios" on back cover is a registered trademark of The Walt Disney Company. Rabbit Publishers 1624 W. Northwest Highway Arlington Heights, IL 60004 Illustrations by Christina Weidman Cover design by Megan Black Interior Design by Lewis Design & Marketing ISBN: 978-1-943785-76-6 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 1. Fiction - Action and Adventure 2. Children's Fiction First Color Edition Printed in U.S.A. Table of Contents Preface . i Family, Friends & Foes . ii 1. Nightmare in Gym Class . 1 2. The Art of War . 21 3. Sealed With a Fist. 41 4. Buried Alive. 55 5. No Way Out . 69 6. Oops! . 81 7. Project Restoration. 93 8. Put to the Test . 115 9. Facing the Music . 137 10. Cinderella Meets Her Prince. 149 Sofi's Letter. 159 Honey Moon's Valentine's Day Spectacular! 161 Creator's Notes . 178 Preface Halloween visited the little town of Sleepy Hollow and never left. Many moons ago, a sly and evil mayor found the powers of darkness helpful in building Sleepy Hollow into “Spooky Town,” one of the country’s most celebrated attractions. -

Tsunami Heights and Limits in 1945 Along the Makran Coast

https://doi.org/10.5194/nhess-2021-53 Preprint. Discussion started: 5 March 2021 c Author(s) 2021. CC BY 4.0 License. 1 Tsunami heights and limits in 1945 along the 2 Makran coast estimated from testimony 3 gathered seven decades later in Gwadar, Pasni 4 and Ormara 5 Hira Ashfaq Lodhi1, Shoaib Ahmed2, Haider Hasan2 6 1Department of Physics, NED University of Engineering & Technology, Karachi, 75270, Pakistan 7 2 Department of Civil Engineering, NED University of Engineering & Technology, Karachi, 75270, Pakistan 8 Correspondence to: Hira Ashfaq Lodhi ([email protected]) 9 Abstract. 10 The towns of Pasni and Ormara were the most severely affected by the 1945 Makran tsuami. The water inundated almost a 11 kilometer at Pasni, engulfing 80% huts of the town while at Ormara tsunami inundated two and a half kilometers washing 12 away 60% of the huts. The plate boundary between Arabian plate and Eurasian plate is marked by Makran Subduction Zone 13 (MSZ). This Makran subduction zone in November 1945 was the source of a great earthquake (8.1 Mw) and of an associated 14 tsunami. Estimated death tolls, waves arrival times, extent of inundation and runup remained vague. We summarize 15 observations of tsunami through newspaper items, eye witness accounts and archival documents. The information gathered is 16 reviewed and quantized where possible to get the inundation parameters in specific and impact in general along the Makran 17 coast. The quantization of runup and inundation extents is based on a field survey or on old maps. 18 1 Introduction 19 The recent tsunami events of 2004 Indian Ocean (Sumatra) tsunami, 2010 (Chile) and 2011 (Tohoku) Pacific Ocean tsunami 20 have highlighted the vulnerability of coastal areas and coastal communities to such events. -

Identifying Special Or Unique Sites in the Great Barrier Reef World Heritage Area for Inclusion in the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Zoning Plan 2003

Identifying Special or Unique Sites in the Great Barrier Reef World Heritage Area for inclusion in the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Zoning Plan 2003 Compiled by Kirstin Dobbs Identifying Special or Unique Sites in the Great Barrier Reef World Heritage Area for inclusion in the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Zoning Plan 2003 Compiled by Kirstin Dobbs © Commonwealth of Australia 2011 Published by the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority ISBN 978 1 876945 66 4 (pdf) This work is copyright. Apart from any use as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part may be reproduced by any process without the prior written permission of the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority. The National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry : Identifying special or unique sites in the Great Barrier Reef World Heritage area for inclusion in the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Zoning Plan 2003 / compiled by Kirstin Dobbs. ISBN 9781921682421 (pdf) Includes bibliographical references. Marine parks and reserves--Queensland--Management. Marine resources--Queensland--Management. Marine resources conservation--Queensland. Great Barrier Reef Marine Park (Qld.)--Management. Dobbs, Kirstin Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority. 333.916409943 This publication should be cited as: Dobbs, Kirstin (comp.) 2011, Identifying special or unique sites in the Great Barrier Reef World Heritage Area for inclusion in the Great Barrier Marine Park Zoning Plan 2003, Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority, Townsville. Requests and inquiries concerning reproduction and rights should be addressed to: Director, Communications 2-68 Flinders Street PO Box 1379 TOWNSVILLE QLD 4810 Australia Phone: (07) 4750 0700 Fax: (07) 4772 6093 [email protected] Comments and inquiries on this document are welcome and should be addressed to: Director, Strategic Advice [email protected] www.gbrmpa.gov.au EXECUTIVE SUMMARY A comprehensive and adequate network of protected areas requires the inclusion of both representative examples of different habitats, and special or unique sites.