Change and Continuity in Libyan Currency

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

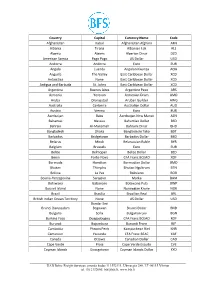

Countries Codes and Currencies 2020.Xlsx

World Bank Country Code Country Name WHO Region Currency Name Currency Code Income Group (2018) AFG Afghanistan EMR Low Afghanistan Afghani AFN ALB Albania EUR Upper‐middle Albanian Lek ALL DZA Algeria AFR Upper‐middle Algerian Dinar DZD AND Andorra EUR High Euro EUR AGO Angola AFR Lower‐middle Angolan Kwanza AON ATG Antigua and Barbuda AMR High Eastern Caribbean Dollar XCD ARG Argentina AMR Upper‐middle Argentine Peso ARS ARM Armenia EUR Upper‐middle Dram AMD AUS Australia WPR High Australian Dollar AUD AUT Austria EUR High Euro EUR AZE Azerbaijan EUR Upper‐middle Manat AZN BHS Bahamas AMR High Bahamian Dollar BSD BHR Bahrain EMR High Baharaini Dinar BHD BGD Bangladesh SEAR Lower‐middle Taka BDT BRB Barbados AMR High Barbados Dollar BBD BLR Belarus EUR Upper‐middle Belarusian Ruble BYN BEL Belgium EUR High Euro EUR BLZ Belize AMR Upper‐middle Belize Dollar BZD BEN Benin AFR Low CFA Franc XOF BTN Bhutan SEAR Lower‐middle Ngultrum BTN BOL Bolivia Plurinational States of AMR Lower‐middle Boliviano BOB BIH Bosnia and Herzegovina EUR Upper‐middle Convertible Mark BAM BWA Botswana AFR Upper‐middle Botswana Pula BWP BRA Brazil AMR Upper‐middle Brazilian Real BRL BRN Brunei Darussalam WPR High Brunei Dollar BND BGR Bulgaria EUR Upper‐middle Bulgarian Lev BGL BFA Burkina Faso AFR Low CFA Franc XOF BDI Burundi AFR Low Burundi Franc BIF CPV Cabo Verde Republic of AFR Lower‐middle Cape Verde Escudo CVE KHM Cambodia WPR Lower‐middle Riel KHR CMR Cameroon AFR Lower‐middle CFA Franc XAF CAN Canada AMR High Canadian Dollar CAD CAF Central African Republic -

Origins of the Libyan Conflict and Options for Its Resolution

ORIGINS OF THE LIBYAN CONFLICT AND OPTIONS FOR ITS RESOLUTION JONATHAN M. WINER MAY 2019 POLICY PAPER 2019-12 CONTENTS * 1 INTRODUCTION * 4 HISTORICAL FACTORS * 7 PRIMARY DOMESTIC ACTORS * 10 PRIMARY FOREIGN ACTORS * 11 UNDERLYING CONDITIONS FUELING CONFLICT * 12 PRECIPITATING EVENTS LEADING TO OPEN CONFLICT * 12 MITIGATING FACTORS * 14 THE SKHIRAT PROCESS LEADING TO THE LPA * 15 POST-SKHIRAT BALANCE OF POWER * 18 MOVING BEYOND SKHIRAT: POLITICAL AGREEMENT OR STALLING FOR TIME? * 20 THE CURRENT CONFLICT * 22 PATHWAYS TO END CONFLICT SUMMARY After 42 years during which Muammar Gaddafi controlled all power in Libya, since the 2011 uprising, Libyans, fragmented by geography, tribe, ideology, and history, have resisted having anyone, foreigner or Libyan, telling them what to do. In the process, they have frustrated the efforts of outsiders to help them rebuild institutions at the national level, preferring instead to maintain control locally when they have it, often supported by foreign backers. Despite General Khalifa Hifter’s ongoing attempt in 2019 to conquer Tripoli by military force, Libya’s best chance for progress remains a unified international approach built on near complete alignment among international actors, supporting Libyans convening as a whole to address political, security, and economic issues at the same time. While the tracks can be separate, progress is required on all three for any of them to work in the long run. But first the country will need to find a way to pull back from the confrontation created by General Hifter. © The Middle East Institute The Middle East Institute 1319 18th Street NW Washington, D.C. -

International Currency Codes

Country Capital Currency Name Code Afghanistan Kabul Afghanistan Afghani AFN Albania Tirana Albanian Lek ALL Algeria Algiers Algerian Dinar DZD American Samoa Pago Pago US Dollar USD Andorra Andorra Euro EUR Angola Luanda Angolan Kwanza AOA Anguilla The Valley East Caribbean Dollar XCD Antarctica None East Caribbean Dollar XCD Antigua and Barbuda St. Johns East Caribbean Dollar XCD Argentina Buenos Aires Argentine Peso ARS Armenia Yerevan Armenian Dram AMD Aruba Oranjestad Aruban Guilder AWG Australia Canberra Australian Dollar AUD Austria Vienna Euro EUR Azerbaijan Baku Azerbaijan New Manat AZN Bahamas Nassau Bahamian Dollar BSD Bahrain Al-Manamah Bahraini Dinar BHD Bangladesh Dhaka Bangladeshi Taka BDT Barbados Bridgetown Barbados Dollar BBD Belarus Minsk Belarussian Ruble BYR Belgium Brussels Euro EUR Belize Belmopan Belize Dollar BZD Benin Porto-Novo CFA Franc BCEAO XOF Bermuda Hamilton Bermudian Dollar BMD Bhutan Thimphu Bhutan Ngultrum BTN Bolivia La Paz Boliviano BOB Bosnia-Herzegovina Sarajevo Marka BAM Botswana Gaborone Botswana Pula BWP Bouvet Island None Norwegian Krone NOK Brazil Brasilia Brazilian Real BRL British Indian Ocean Territory None US Dollar USD Bandar Seri Brunei Darussalam Begawan Brunei Dollar BND Bulgaria Sofia Bulgarian Lev BGN Burkina Faso Ouagadougou CFA Franc BCEAO XOF Burundi Bujumbura Burundi Franc BIF Cambodia Phnom Penh Kampuchean Riel KHR Cameroon Yaounde CFA Franc BEAC XAF Canada Ottawa Canadian Dollar CAD Cape Verde Praia Cape Verde Escudo CVE Cayman Islands Georgetown Cayman Islands Dollar KYD _____________________________________________________________________________________________ -

Libyan Gold Dinar Plan and Us-Nato Retort

Extremism, Violence and Jihad 1 The Government: Research Journal of Political Science Vol. VI LIBYAN GOLD DINAR PLAN AND US-NATO RETORT Prof. Dr. Mughees Ahmed1 Zainab Murtaza2 Tanzila Shahzadi3 Abstract Africa is one of the richest continents of world, with great amount of unexplored mineral wealth and gold. Africa had been kept in wars for centuries. Libya, is African state, had 144-ton gold, relatively, United States had no gold. The American institutions have controlled the money supply and determine to control everything. Gaddafi understood their policy; therefore, he did everything possible to make Libya independent, and self-sufficient. They created conditions for aid to other countries. It can be happened that demanding countries including Libya give up their gold to powerful financial system which was never happened in Gaddafi era. Moreover, Gaddafi made overwhelming policies which made Libya economically independent with its own oil, water, food, and even its own state bank. The state had become richest state of Africa. For recent decades, World Bank and Monetary Fund, the US instruments, have been suppress African real development. Gaddafi’s gold dinar plan would be a tsunami for western economy, especially for dollar. United States intervened militarily in Libya under Obama administration for American interest. 1 Chairman Department of Political Science & International Relation, Government College University Faisalabad 2 Corresponding Author, Department of Political Science & International Relation, Government College University Faisalabad 3 Research Scholar, Department of Political Science & International Relation, Government College University Faisalabad 116 The Government Keywords: Gold Dinar Plan, Economic growth, Social development, Gold-based Africa, Arab Spring Introduction Gold Dinar The rich resources Libya was the one of last nation which had its own state banking system and had control over its personal money supply. -

FAO Country Name ISO Currency Code* Currency Name*

FAO Country Name ISO Currency Code* Currency Name* Afghanistan AFA Afghani Albania ALL Lek Algeria DZD Algerian Dinar Amer Samoa USD US Dollar Andorra ADP Andorran Peseta Angola AON New Kwanza Anguilla XCD East Caribbean Dollar Antigua Barb XCD East Caribbean Dollar Argentina ARS Argentine Peso Armenia AMD Armeniam Dram Aruba AWG Aruban Guilder Australia AUD Australian Dollar Austria ATS Schilling Azerbaijan AZM Azerbaijanian Manat Bahamas BSD Bahamian Dollar Bahrain BHD Bahraini Dinar Bangladesh BDT Taka Barbados BBD Barbados Dollar Belarus BYB Belarussian Ruble Belgium BEF Belgian Franc Belize BZD Belize Dollar Benin XOF CFA Franc Bermuda BMD Bermudian Dollar Bhutan BTN Ngultrum Bolivia BOB Boliviano Botswana BWP Pula Br Ind Oc Tr USD US Dollar Br Virgin Is USD US Dollar Brazil BRL Brazilian Real Brunei Darsm BND Brunei Dollar Bulgaria BGN New Lev Burkina Faso XOF CFA Franc Burundi BIF Burundi Franc Côte dIvoire XOF CFA Franc Cambodia KHR Riel Cameroon XAF CFA Franc Canada CAD Canadian Dollar Cape Verde CVE Cape Verde Escudo Cayman Is KYD Cayman Islands Dollar Cent Afr Rep XAF CFA Franc Chad XAF CFA Franc Channel Is GBP Pound Sterling Chile CLP Chilean Peso China CNY Yuan Renminbi China, Macao MOP Pataca China,H.Kong HKD Hong Kong Dollar China,Taiwan TWD New Taiwan Dollar Christmas Is AUD Australian Dollar Cocos Is AUD Australian Dollar Colombia COP Colombian Peso Comoros KMF Comoro Franc FAO Country Name ISO Currency Code* Currency Name* Congo Dem R CDF Franc Congolais Congo Rep XAF CFA Franc Cook Is NZD New Zealand Dollar Costa Rica -

Tripoli, Libya Destination Guide

Tripoli, Libya Destination Guide Overview of Tripoli The Libyan capital of Tripoli is ordinarily filled with wonderful sights, charm and hospitality. Situated on the Mediterranean Sea in the northwest of the country, Tripoli has one of the largest harbours in North Africa; it is a city constantly abuzz with activity. The many historical sites and ruins dotted throughout the city stand testament to its rich and fascinating history. Visitors to Tripoli can stroll in the bustling bazaars, shopping for holiday souvenirs and trinkets as well as beautiful textiles and exquisite jewellery. Tourists are spoilt for choice when it comes to the amazing sights in and around the city, from the Red Castle to the Gurgi and Karamanli Mosques. Tripoli is overflowing with places to discover and sights to behold. Unfortunately, this wonderful city has seen hard times in recent years thanks to rebel and terrorist activity during and in the aftermath of civil war. While its many wonders remain undimmed, travellers are advised to do careful research before visiting the city, and to take note of the serious travel warnings issued by various international governments. Key Facts Language: The official language of Libya is Arabic (used for all official business), though some Italian and English is spoken, especially in the cities. Passport/Visa: Most foreign passengers require a visa to enter Libya. Tourist visas must be organised in advance, but can sometimes be issued on arrival; provided that travellers are holding a copy of a letter issued by the Libyan immigration authorities, confirming that a visa will be granted to them upon their arrival at the airport. -

List of Currencies of All Countries

The CSS Point List Of Currencies Of All Countries Country Currency ISO-4217 A Afghanistan Afghan afghani AFN Albania Albanian lek ALL Algeria Algerian dinar DZD Andorra European euro EUR Angola Angolan kwanza AOA Anguilla East Caribbean dollar XCD Antigua and Barbuda East Caribbean dollar XCD Argentina Argentine peso ARS Armenia Armenian dram AMD Aruba Aruban florin AWG Australia Australian dollar AUD Austria European euro EUR Azerbaijan Azerbaijani manat AZN B Bahamas Bahamian dollar BSD Bahrain Bahraini dinar BHD Bangladesh Bangladeshi taka BDT Barbados Barbadian dollar BBD Belarus Belarusian ruble BYR Belgium European euro EUR Belize Belize dollar BZD Benin West African CFA franc XOF Bhutan Bhutanese ngultrum BTN Bolivia Bolivian boliviano BOB Bosnia-Herzegovina Bosnia and Herzegovina konvertibilna marka BAM Botswana Botswana pula BWP 1 www.thecsspoint.com www.facebook.com/thecsspointOfficial The CSS Point Brazil Brazilian real BRL Brunei Brunei dollar BND Bulgaria Bulgarian lev BGN Burkina Faso West African CFA franc XOF Burundi Burundi franc BIF C Cambodia Cambodian riel KHR Cameroon Central African CFA franc XAF Canada Canadian dollar CAD Cape Verde Cape Verdean escudo CVE Cayman Islands Cayman Islands dollar KYD Central African Republic Central African CFA franc XAF Chad Central African CFA franc XAF Chile Chilean peso CLP China Chinese renminbi CNY Colombia Colombian peso COP Comoros Comorian franc KMF Congo Central African CFA franc XAF Congo, Democratic Republic Congolese franc CDF Costa Rica Costa Rican colon CRC Côte d'Ivoire West African CFA franc XOF Croatia Croatian kuna HRK Cuba Cuban peso CUC Cyprus European euro EUR Czech Republic Czech koruna CZK D Denmark Danish krone DKK Djibouti Djiboutian franc DJF Dominica East Caribbean dollar XCD 2 www.thecsspoint.com www.facebook.com/thecsspointOfficial The CSS Point Dominican Republic Dominican peso DOP E East Timor uses the U.S. -

PREDATORY ECONOMIES in EASTERN LIBYA the Dominant Role of the Libyan National Army

PREDATORY ECONOMIES IN EASTERN LIBYA The dominant role of the Libyan National Army A REPORT BY NORIA RESEARCH JUNE 2019 Predatory economies in eastern Libya The dominant role of the Libyan National Army Report by Noria Research JUNE 2019 Cover photo: Al-Sharara oilfield, Libya; Javier Blas/Wikimedia Commons © 2019 Global Initiative Against Transnational Organized Crime. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means without permission in writing from the Global Initiative. Please direct inquiries to: The Global Initiative against Transnational Organized Crime WMO Building, 2nd Floor 7bis, Avenue de la Paix CH-1211 Geneva 1 Switzerland www.GlobalInitiative.net Contents Executive summary ............................................................................................................................ 1 Methodology ...................................................................................................................................... 2 A brief introduction to the LNA ................................................................................................... 3 The LNA’s use of force: Racketeering, extortion and misappropriation of public funds ...................................................................................................................................... 4 Urban warfare and militia-like behaviour in Benghazi, 2014 to 2017 ..................................... 4 Misappropriation of state funds and access to cash .................................................................. -

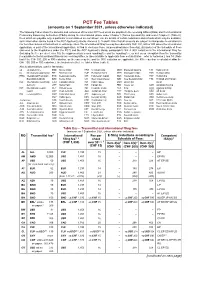

PCT Fee Tables I(B)

PCT Fee Tables (amounts on 1 September 2021, unless otherwise indicated) The following Tables show the amounts and currencies of the main PCT fees which are payable to the receiving Offices (ROs) and the International Preliminary Examining Authorities (IPEAs) during the international phase under Chapter I (Tables I(a) and I(b)) and under Chapter II (Table II). Fees which are payable only in particular circumstances are not shown; nor are details of certain reductions and refunds which may be available; such information can be found in the PCT Applicant’s Guide, Annexes C, D and E. Note that all amounts are subject to change due to variations in the fees themselves or fluctuations in exchange rates. The international filing fee may be reduced by CHF 100, 200 or 300 where the international application, or part of the international application, is filed in electronic form, as prescribed under Item 4(a), (b) and (c) of the Schedule of Fees (annexed to the Regulations under the PCT) and the PCT Applicant’s Guide, paragraph 5.189. A 90% reduction in the international filing fee (including the fee per sheet over 30), the supplementary search handling fee and the handling fee, as well as an exemption from the transmittal fee payable to the International Bureau as receiving Office, is also available to applicants from certain States—refer to footnotes 2 and 14. (Note that if the CHF 100, 200 or 300 reduction, as the case may be, and the 90% reduction are applicable, the 90% reduction is calculated after the CHF 100, 200 or 300 reduction.) The footnotes to the Fee Tables follow Table II. -

Currencies of the World

The World Trade Press Guide to Currencies of the World Currency, Sub-Currency & Symbol Tables by Country, Currency, ISO Alpha Code, and ISO Numeric Code € € € € ¥ ¥ ¥ ¥ $ $ $ $ £ £ £ £ Professional Industry Report 2 World Trade Press Currencies and Sub-Currencies Guide to Currencies and Sub-Currencies of the World of the World World Trade Press Ta b l e o f C o n t e n t s 800 Lindberg Lane, Suite 190 Petaluma, California 94952 USA Tel: +1 (707) 778-1124 x 3 Introduction . 3 Fax: +1 (707) 778-1329 Currencies of the World www.WorldTradePress.com BY COUNTRY . 4 [email protected] Currencies of the World Copyright Notice BY CURRENCY . 12 World Trade Press Guide to Currencies and Sub-Currencies Currencies of the World of the World © Copyright 2000-2008 by World Trade Press. BY ISO ALPHA CODE . 20 All Rights Reserved. Reproduction or translation of any part of this work without the express written permission of the Currencies of the World copyright holder is unlawful. Requests for permissions and/or BY ISO NUMERIC CODE . 28 translation or electronic rights should be addressed to “Pub- lisher” at the above address. Additional Copyright Notice(s) All illustrations in this guide were custom developed by, and are proprietary to, World Trade Press. World Trade Press Web URLs www.WorldTradePress.com (main Website: world-class books, maps, reports, and e-con- tent for international trade and logistics) www.BestCountryReports.com (world’s most comprehensive downloadable reports on cul- ture, communications, travel, business, trade, marketing, -

Republic of Tunisia Impact of the Libya Crisis on the Tunisian Economy

Report No: ACS16340 . Republic of Tunisia Public Disclosure Authorized Impact of the Libya Crisis on the Tunisian Economy . February 2017 Public Disclosure Authorized . GMF05 MIDDLE EAST AND NORTH AFRICA Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Macroeconomics & Fiscal Management Global Practice Middle East and North Africa Region Contents Acknowledgements .................................................................................................................................... v Executive Summary .................................................................................................................................. 1 Introduction ................................................................................................................................................ 4 Chapter 1 Libyan Households in Tunisia: How Many and Who are They? ............................ 10 ....................................................................................................................................... 10 ......................................... 11 ......................................................... 12 ...................... 18 ................................................................................................................................................... 22 ................................................................. 26 Chapter 2 The Impact on Financial Flows and the Banking System ......................................... 30 ...................................................................................................................................... -

Libya's Liquidity Crunch and the Dinar's Demise

Libya’s Liquidity Crunch and the Dinar’s Demise: Psychological and Macroeconomic Dimensions of the current crisis By Jason Pack 21 April, 2017 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Libya faces an ever-worsening currency and liquidity crisis which cannot be surmounted without a stable political solution that definitively concludes the struggle for power and legitimacy ongoing since 2014. Yet, the root of the crisis lies not in politics but in the deepening distrust toward Libya’s public financial system as a whole. The banking system, which appropriates Libya’s oil income and sovereign wealth, is the locus of unique popular disdain. In addition, General National Congress Prime Minister Ali Zeidan vastly expanded the budget in 2012 and 2013, when oil prices were high and Libya was relatively stable; this left his successors with a range of financial commitments they cannot meet. Compounding these budgetary woes is the emergence of a new predatory social and criminal institution: currency traders who double as smugglers of foreign currency out of Libya. These villains try to capitalize on three overlapping factors: the public’s distrust of the banking sector, their need for foreign currency, and the spread between the official and black-market rates of the Libyan dinar. These currency ‘smugglers’ managed to drive the value of the dinar down from 6 to 10 dinars per U.S. dollar in the space of three days in mid- April 2017, while profiting from the trading arbitrage opportunities thus generated. 1 US-LIBYA BUSINESS ASSOCIATION 1625 K STREET, NW, SUITE 200 • WASHINGTON, DC 20006 202-464-2038 • [email protected] THE VIEWS AND ANALYSIS EXPRESSED IN THIS REPORT DO NOT NECESSARILY REPRESENT THOSE OF USLBA MEMBER COMPANIES Given the existing budgetary commitments and the psychological legacy of the past few years even if a political resolution to the post-2014 civil war was miraculously achieved, this cannot by itself solve the financial crisis.