Union College 2013-2014 Academic Register

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1. Universalist Churches—United States—History—18Th Century

The Universalist Movement in America 1770–1880 Recent titles in religion in america series Harry S. Stout, General Editor Saints in Exile Our Lady of the Exile The Holiness-Pentecostal Experience in Diasporic Religion at a Cuban Catholic African American Religion and Culture Shrine in Miami Cheryl J. Sanders Thomas A. Tweed Democratic Religion Taking Heaven by Storm Freedom, Authority, and Church Discipline Methodism and the Rise of Popular in the Baptist South, 1785–1900 Christianity in America Gregory A. Willis John H. Wigger The Soul of Development Encounters with God Biblical Christianity and Economic An Approach to the Theology of Transformation in Guatemala Jonathan Edwards Amy L. Sherman Michael J. McClymond The Viper on the Hearth Evangelicals and Science in Mormons, Myths, and the Historical Perspective Construction of Heresy Edited by David N. Livingstone, Terryl L. Givens D. G. Hart, and Mark A. Noll Sacred Companies Methodism and the Southern Mind, Organizational Aspects of Religion and 1770–1810 Religious Aspects of Organizations Cynthia Lynn Lyerly Edited by N. J. Demerath III, Princeton in the Nation’s Service Peter Dobkin Hall, Terry Schmitt, Religious Ideals and Educational Practice, and Rhys H. Williams 1868–1928 Mary Lyon and the Mount Holyoke P. C. Kemeny Missionaries Church People in the Struggle Amanda Porterfield The National Council of Churches and the Being There Black Freedom Movement, 1950–1970 Culture and Formation in Two James F. Findlay, Jr. Theological Schools Tenacious of Their Liberties Jackson W. Carroll, Barbara G. Wheeler, The Congregationalists in Daniel O. Aleshire, and Colonial Massachusetts Penny Long Marler James F. -

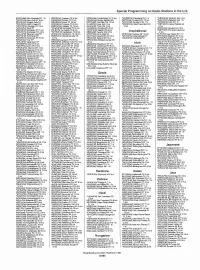

Special Programming on Radio Stations in the US Inspirational Irish

Special Programming on Radio Stations in the U.S. WOOX(AM) New Rochelle NV 1 hr WCDZ(FM) Dresden TN 4 hrs WRRA AMj Frederiksted VI 12 hrs ' WCSN(FM) Cleveland OH 1 hr 'WBRS(FM) Waltham MA 4 hrs WKCR-FM New York NY 2 hrs WSDO(AM) Dunlap TN 7 hrs KGNW AM) Burien -Seattle WA WKTX(AM) Cortland OH 12 hrs WZLY(FM) Wellesley MA 1 hr WHLD(AM) Niagara Falls NY WEMB(AM) Erwin TN 10 hrs KNTR( ) Ferndale WA 10 hrs WWKTL(FM) Struthers OH 1 hr WVFBE(FM) Flint MI 1 hr WXLG(FM) North Creek NY WHEW AM Franklin TN 3 hrs KLLM(FM) Forks WA 4 hrs WVQRP(FM) West Carrollton OH WVBYW(FM) Grand Rapids MI WWNYO(FM) Oswego NY 3 hrs WMRO AM Gallatin TN 13 tirs KVAC(AM) Forks WA 4 hrs 3 hrs 2 hrs WWXLU(FM) Peru NY WLMU(FM) Harrogate TN 4 hrs 'KAOS(FM) Olympia WA 2 hrs WSSJ(AM) Camden NJ 2 hrs WDKX(FM) Rochester NY 7 hrs WXJB -FM Harrogate TN 2 hrs KNHC(FM) Seattle WA 6 hrs WGHT(AM) Pompton Lakes NJ WWRU -FM Rochester NY 3 hrs WWFHC(FM) Henderson TN 5 hrs KBBO(AM) Yakima WA 2 hrs Inspirational 2 hrs WSLL(FM) Saranac Lake NY WHHM -FM Henderson TN 10 tirs WTRV(FM) La Crosse WI WFST(AM) Carbou ME 18 hrs KLAV(AM) Las Vegas NV 1 hr WMYY(FM) Schoharie NY WQOK(FM) Hendersonville TN WLDY(AM) Ladysmith 1M 3 hrs WVCIY(FM) Canandaigua NY WNYG(AM) Babylon NY 4 firs WVAER (FM) Syracuse NY 3 hrs 6 hrs WBJX(AM) Raane WI 8 hrs ' WCID(FM) Friendship NY WVOA(FM) DeRuyter NY 1 hr WHAZ(AM) Troy NY WDXI(AM) Jackson TN 16 hrs WRCO(AM) Rlohland Center WI WSI(AM) East Syracuse NY 1 hr WWSU(FM) Watertown NY WEZG(FM) Jefferson City TN 4 firs 3 hrs Irish WVCV FM Fredonia NY 3 hrs WONB(FM) Ada -

Archives of Michigan Portrait Collection Archives of Michigan

Last Name First Name Initial RG # Collection Telesphore St. Pierre bio Temple Ansel F. See Bio Group, Republicans of MI Temptations the See ethnic and racial groups, Afro-Americans Tenbrook William L. Tendler Mitchell RG 66-82 records of Civil Rights Commission, B12 Tenney family Tenney Harriet A. Mrs. 1834-1899, state librarian, April 5, 1869 - March 1891. Member of Lansing Tenney Harriet Edgerton MS 85-154 Tenney Jesse Eugene MS 85-154 Tenney Judge Terbush Jay M. Jr. Terrell Beatrice C. RG Terrell Ethel Terriff William W. Terrill Bob RG 82-6 Terrill J. F. Mr and Mrs see Eaton County Collection Terry Brig. General Henry D. Terry Joseph Terryah Thomas Ivory RG 73-27 See Centennial Farms Oakland County Terwilliger Wells F. See social life and customs, hobbyists Tesner Arthur P. RG 76-62 Lt. Military Affairs Teunis John H. MS 78-118 Tevis Lloyd P. see organizations professional American Society of Mammalogists, file 1378 Thaden John F. Thal Louis see War, Spanish American Veterans Municipal Council Thatcher Fent Edwin Napoleon Thatcher Marshal P. Thatcher Theo T. see Bio Group, House of Reps, 1933-34 outsize; Bio Group, House of Reps, Wednesday, February 28, 2007 Page 451 of 515 Archives of Michigan Portrait Collection Archives of Michigan: www.michigan.gov/archivesofmi Order copies by calling (517) 373-1408 E-mail: [email protected] Last Name First Name Initial RG # Collection Thatcher Thomas T. clerk, assistant clerk, see also Bio Group, House of Reps, 1975-76 214 D7 F1; Bio Thatcher Thomas T. continued: Bio Group, House of Reps, 1965-66 outsize; 1969-70 outsize Thayer Della Thayer George W. -

UPDATED COMMUNITY RELATIONS PLAN WATERVLIET ARSENAL, Watervliet, New York

FINAL UPDATED COMMUNITY RELATIONS PLAN WATERVLIET ARSENAL, Watervliet, New York RCRA FACILITY INVESTIGATIONS AND CORRECTIVE MEASURES AT SIBERIA AREA AND MAIN MANUFACTURING AREA Baltimore Corps of Engineers Baltimore, Maryland Prepared by: Malcolm Pirnie, Inc. 15 Cornell Road Latham, New York 12110 October 2000 0285-701 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page 1.0 INTRODUCTION AND BACKGROUND...........................................................1-1 1.1 Site Location.................................................................................................1-3 1.2 Site History...................................................................................................1-3 1.3 Environmental Studies....................................................................................1-6 2.0 COMMUNITY BACKGROUND..........................................................................2-1 2.1 Community Demographics and Employment...................................................2-1 2.2 Community Involvement History....................................................................2-4 2.3 Community Interview Program.......................................................................2-7 2.4 Community Issues and Concerns .................................................................2-16 2.5 Technical Assistance Grants.........................................................................2-18 3.0 COMMUNITY RELATIONS PROGRAM............................................................3-1 3.1 Goals and Objectives ....................................................................................3-1 -

Cette Publication a Été Numérisée À Partir D’Une Copie Papier Et Peut Contenir Des Différences Avec La Publication Originale

This publication has been scanned from a paper copy and may have some discrepancies from the original publication. _____ Cette publication a été numérisée à partir d’une copie papier et peut contenir des différences avec la publication originale. _____ Diese Veröffentlichung wurde von einer Papierkopie gescannt und könnte Abweichungen von der originalen Veröffentlichung aufweisen. _____ Esta publicación ha sido escaneada a partir de una copia en papel y puede que existan divergencias en relación con la publicación original. n:\orgupov\shared\publications\_publications_edocs\electronic_pub\disclaimer_scanned_documents_publications.docx OPOV Publication No. 438(B) ( DPOV) PlANT VARIETY PROTECTION Gazette and Newsletter of the International Union for the Protection of New Varieties of Plants ( UPOV) No. 64 August 1991 Geneva CON'l'BN'l'S Page GAZETTE Extension of Protection to Further Genera and Species Poland 2 United Kingdom ••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• 19 NEWSLETTER Meaber States Australia: Modification of Fees 50 United Kingdom: Modification of Fees •••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• 50 Ron-Member States Czechoslovakia: Operation of the System for the legal protection of new varieties of plants and breeds of animals ••••••••••••••••••.••••••••••• 79 Legislation Czechoslovakia: Law on the Legal Protection of the Varieties of Plants and Breeds of Animals . • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • 53 Czechoslovakia: Decree of the Federal Ministry of Agriculture and Food Concerning -

3356770.Pdf (3.910Mb)

Copyright © 2008 Aaron Menikoff All rights reserved. The Southern Baptist Theological Seminary has permission to reproduce and disseminate this document in any form by any means for purposes chosen by the Seminary, including, without limitation, preservation or instruction. PIETY AND POLITICS: BAPTIST SOCIAL REFORM IN AMERICA, 1770-1860 A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of The Southern Baptist Theological Seminary In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy by Aaron Menikoff October 2008 UMI Number: 3356770 Copyright 2009 by Menikoff, Aaron All rights reserved INFORMATION TO USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleed-through, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. UM^ . I<§> UMI Microform 3356770 Copyright2009by ProQuest LLC All rights reserved. This microform edition is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 APPROVAL SHEET PIETY AND POLITICS: BAPTIST SOCIAL REFORM IN AMERICA, 1770-1860 Aaron Menikoff Read and Approved by: Gregory A. Wills (Supervisor) omas J./Wettle, \JJJt>S> Russell D. Moore Date a a/cy* To Deana, my wife and friend TABLE OF CONTENTS Page PREFACE vi Chapter 1. INTRODUCTION 1 An Evangelical Impulse 4 A Search for Virtue 11 Real Social Reform 13 Thesis and Summary 19 2. -

August-Sept 1993

Opens Broadutell , Pratt, Shayne IamesWilliams in Hot Vocal Cancert! Sixth Season Teresa Broadwell, Colleen Pratt and ]ody Shayne will who some consider the appear with the Peg answer to the DirtY Northern Delaney Trio in a most This concert Dozen JazzBand. unusual outing. These will be followed on October 15 three dynamic singers and by the return of TanaReid led band leaders in their own by the renown bassist Rufus at the Reid and the award winning right, will appear drummer Akira Tana. this Rensselaerville Ins titute on group much praise and August 15th at 4Pm. enthusiastic crowds in their last visit two years ago. On They'tt be doing standards October 29 we introduce PaPo and originals; singing solos Vasquez and his Pulsating and hip harmony. We've combination of traditional been promised a verY "hot" Puerto Rican and Afro{uban version of Horace Silver's rhythms called Bomba laz?. - Sermonette. H6'[ appear in a sextet with the The Institute is onRte 85 lamesWiltiams senational percussionist Milton extended. Tickets are $7 for Cardona and Mario Rivera, the adults, $3.50 for under 17 and f o^"t Williams, the exciting spectacular saxaPhonist who Seniors. Call 797-3783 for 'New York City pianist will h1s often appeared with Tito reservations open APFJ's FallJazz series on Puente. INSIDE September 17th. ShortllY after See page 6 and 7 for order forms this concert he'lI apPear at the and more in-formation about how 200 Words................ ....p.2 Blue Note in Manhattan. Mr. you can see these exciting musicians My So1o.. -

Stablished in 1798 on the Edge of Town As Columbia's First Public

Memorializing the deeds, trials, tribulations and federal architect; the Washington Monument and the with a number of other Federalists, permitted the election US Treasury Building are his creations. Mills became of Thomas Jefferson. BULL STREET Christian faith of individuals buried here, the churchyard and church records reveal the early an elder of this church in 1824. 9. HENRY WILLIAM DESAUSSURE (1763-1839) 29 N 26 27 history of our city, state and nation. Early graves 4. GEN. ADLEY H. GLADDEN FAMILY As a Revolutionary soldier, defended Charleston reflect Columbia as anew immigrant city with Monument to the wife and daughter of Gen. A. H. against the siege of Sir Henry Clinton. Read law under the 28 25 settlers from England, Scotland, Ireland, Connecticut, Gladden, who himself was killed at the Battle of Shiloh noted Philadelphia lawyer Jared Ingesoll, in which city he Massachusetts, Pennsylvania, Vermont, Virginia and in 1862 and is buried elsewhere; in the Mexican War, was first admitted to the Bar. Returned to South Carolina places within South Carolina. Many early residents following the death of senior officers, he commanded and became a member of the convention that framed the buried here were active in national political matters the Palmetto Regiment as major at Churubusco, South Carolina Constitution in 1789. Was President of and dealt with Washington, Adams, Jefferson, Chapaultepec and Mexico City; served as intendant the South Carolina Senate when it first met in Columbia Hamilton, Polk, Jackson, Webster and Calhoun. (mayor) of Columbia, 1851-1852. The bronze Palmetto in 1791; appointed Superintendent of the Mint in tree at the State House memorializes him and those Philadelphia by President Washington; a member of Tombstones record military service in the who died with him in Mexico. -

October 2012 ERA Bulletin.Pub

The ERA BULLETIN - OCTOBER, 2012 Bulletin Electric Railroaders’ Association, Incorporated Vol. 55, No. 10 October, 2012 The Bulletin NEW YORK & QUEENS CARS QUIT 75 YEARS AGO Published by the Electric The first northern Queens surface transit depend on short-haul business instead. Railroaders’ Association, horse car line was Dutch Kills (31st Street), Deficits, which had been increasing for sev- Incorporated, PO Box 3323, New York, New which started operating in 1869. Within a few eral years, rose rapidly during and after York 10163-3323. years, several small horse car lines provided World War I because of the rising cost of la- service. They were leased and merged into bor and materials. But Mayor Hylan and the the Steinway Railway Company, which was other city officials insisted on keeping the For general inquiries, incorporated March 30, 1892. five-cent fare. contact us at bulletin@ erausa.org or by phone NY&Q’s predecessor started operating the In the early 1920s, IRT, which subsidized at (212) 986-4482 (voice Calvary Line in 1874. When the New York & NY&Q, was on the verge of bankruptcy, but mail available). ERA’s Queens County Railway Company was incor- was able to remain solvent by reducing its website is porated on September 16, 1896, it bought work force. It converted more than a thou- www.erausa.org. the Steinway Railway Company. In 1903, the sand cars to MUDC (Multiple Unit Door Con- Editorial Staff: Interborough Rapid Transit Company as- trol) and installed turnstiles in most of the Editor-in-Chief: sumed control of NY&Q by buying the majori- stations. -

Brooklyn and the Bicycle

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works Publications and Research New York City College of Technology 2013 Brooklyn and the Bicycle David V. Herlihy How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/ny_pubs/671 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] Bikes and the Brooklyn Waterfront: Past, Present, and Future Brooklyn and the Bicycle by David V. Herlihy Across the United States, cycling is flourishing, not only as a recreational activity but also as a “green” and practical means of urban transportation. The phenomenon is particularly pronounced in Brooklyn, a large and mostly flat urban expanse with a vibrant, youthful population. The current national cycling boom encompasses new and promising developments, such as a growing number of hi-tech urban bike share networks, including Citi Bike, set to launch in New York City in May 2013. Nevertheless, the present “revival” reflects a certain historical pattern in which the bicycle has swung periodically back into, and out of, public favor. I propose to review here the principal American cycling booms over the past century and a half to show how, each time, Brooklyn has played a prominent role. I will start with the introduction of the bicycle itself (then generally called a “velocipede” from the Latin for fast feet), when Brooklyn was arguably the epicenter of the nascent American bicycle industry. 1 Bikes and the Brooklyn Waterfront: Past, Present, and Future Velocipede Mania The first bicycle craze, known then as “velocipede mania,” struck Paris in mid- 1867, in the midst of the Universal Exhibition. -

Special Programing KCIC(FM) Grand Junction

Special Programing KCIC(FM) Grand Junction. *WVSH Huntington, IN 4 hrs. KLTF Little Falls, MN 1.5 hrs. WITR(FM) Henrietta, NY 3 hrs. CO 10 hrs. 'WJEL(FM) Indianapolis 5 hrs. KTIS -FM Minneapolis, MN 6 WSHR(FM) Lake KMSA(FM) Grand Junction, *WNAS(FM) New Albany. IN 1 hrs. Ronkinkoma, NY 5 hrs. CO 6 hrs. hr. KUOM Minneapolis, MN 16 WLFH Little Falls, NY 1 hr. Manchester, NY 2 hrs. WRKK -FM Birmingham, AL 1 KVLE Gunnison, CO 3 hrs. W BKE-FM North hrs. WKGL Middletown, hr. KWSB -FM Gunnison, CO 3 IN 20 hrs. KFAI(FM) Minneapolis. MN 5 WNYU -FM New York, NY 1 hr. WNDA(FM) Huntsville, AL 8 hrs. WNWI Valparaiso, IN 2 hrs. hrs. WCHN Norwich, NY 2.2 hrs. hrs. KVNF(FM) Paonia, CO 12 hrs. WVUB(FM) Vincennes, IN 8 *KRLX(FM) Northfield, MN 12 WONT(FM) Oneonta, NY 9 hrs. WUAL -FM Tuscaloosa, AL 6 KFEL Pueblo, CO 2 hrs. hrs. hrs. 'WRHO(FM) Oneonta, NY 2 hrs. KTSC -FM Pueblo, CO 5 hrs. KCOE -FM Cedar Rapids, IA 2 KYMN Northfield, MN 2 hrs. hrs. KNIK -FM Anchorage, AK 10 KVRH -FM Salida, CO 3 hrs. hrs. KTIG(FM) Pequot Lakes, MN 2 WALK Patchogue, NY 13 hrs. hrs. KSTC -FM Sterling, CO 15 hrs. *KWLC Decorah, IA 10 hrs. hrs. WHRC -FM Port Henry, NY 2 'KSKA Anchorage, AK 20 hrs. KVMT(FM) Vail, CO 12 hrs. KDIC(FM) Grinnell, IA 12 hrs. KNXR(FM) Rochester, MN 4 hrs. 'KUAC(FM) Fairbanks. AK 40 KJCO(FM) Yuma, CO 2 hrs. -

National Register of Historic Places Continuation Sheet Brookdale Farm Historic District Monmouth County, NJ Section Number 7 Page 1

NPS Form 10-900 OMB No. 1024-0018 United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations of eligibility for individual properties or districts. See instructions in How to Complete the National Register of Historic Places Registration Form (National Register Bulletin 16A). Complete each item by marking "x" in the appropriate box or by entering the information requested. If an item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable." For functions, architectural classification, materials and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories listed in the instructions. Place additional entries and narrative items on continuation sheets (NPS Form 10-900a). Use a typewriter, word processor, or computer, to complete all items. ` historic name Brookdale Farm Historic District other names/site number Thompson Park 2. Location street & number 805 Newman Springs Road not for publication city or town Middletown Township vicinity state New Jersey code NJ county Monmouth code 025 zip code 07738 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act, as amended, I certify that this nomination request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property meets does not meet the National Register criteria. I recommend that this property be considered significant nationally statewide locally. See continuation sheet for additional comments.