Robert A. Baade and Victor A. Matheson

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Winning Solutions Gaining New Ground

WINNING SOLUTIONS GAINING NEW GROUND 2011 ANNUAL REPORT 2011 HIGHLIGHTS TransForce generated record revenue and EBIT in spite of an economic environment characterized by sluggish growth. Through strategic expansion, steady adherence to its core business model, and rigorous concentration on operating efficiency, the Company continued to grow shareholder value. • During the year, TransForce completed three significant acquisi- tions in two highly strategic sectors for the Company. Another important acquisition was completed shortly after year end. • The Company’s margins were protected as TransForce OUR MISSION leveraged its network by optimizing asset utilization and To establish itself as a leader in the North American implementing state-of-the-art technology. transportation and logistics industry through strategic, profitable acquisitions and partnerships. TransForce will • The Company’s financial position and cash flow generation create shareholder value by fostering a positive work were both strong, providing the financial flexibility to environment to leverage the skills of its team of dedicated continue TransForce’s acquisition strategy. professionals and provide creative solutions tailored to specific customer needs. Dynamex: The acquisition of Texas-based Dynamex significantly strengthened TransForce’s continental footprint in the Package and Courier segment. The addition of this respected brand has significantly enhanced the Company’s offering for both existing and potential new clients. The integration of Dynamex’s services into the TransForce network promises to open substantial new CORPORATE PROFILE markets for the Company in the fragmented U.S. market. TransForce Inc. is a North American leader in the transporta- Loomis Express: TransForce’s acquisition of the domestic assets tion and logistics industry. -

National Hockey League

NATIONAL HOCKEY LEAGUE {Appendix 4, to Sports Facility Reports, Volume 18} Research completed as of August 7, 2017 Anaheim Ducks Principal Owner: Anaheim Ducks Hockey Club, LLC & Anaheim Arena Management, LLC; headed by Henry and Susan Samueli Year Established: 1992 Team Website Twitter: @AnaheimDucks Most Recent Purchase Price ($/Mil): $75 (2005) Current Value ($/Mil): $415 Percent Change From Last Year: +4% Arena: Honda Center Date Built: 1993 Facility Cost ($/Mil): $123 Percentage of Arena Publicly Financed: 100% Facility Financing: Publicly Funded; Ogden Entertainment is assuming the debt for the city- issued bonds. Facility Website Twitter: @HondaCenter UPDATE: In June 2017, Lottogopher Holdings, Inc. entered into a sponsorship agreement with the Anaheim Ducks. Lottogopher will focus on offering promotional giveaways to Ducks’ fans during the 2017- 18 season. The cities of Anaheim and Long Beach have been added to Los Angeles’s bid for the 2024 Olympics. The Honda Center and multiple Long Beach facilities would stage various Olympic events in an effort to spread the games across southern California. NAMING RIGHTS: In October 2006, American Honda Motor Co. agreed to pay $60.45 million over fifteen years for naming rights that expire in 2020. © Copyright 2017, National Sports Law Institute of Marquette University Law School Page 1 Arizona Coyotes Principal Owner: Andrew Barroway became the sole owner after Barroway bought out the team’s minority owners on June 12, 2017. Year Established: 1979 as the Winnipeg Jets and moved to Phoenix in 1996 where it became the Coyotes. Team Website Twitter: @ArizonaCoyotes Most Recent Purchase Price ($/Mil): $170 (2013) (In 2014, Barroway purchased a majority share of the franchise for $152.5 million. -

TICKETS for KIDS® Charities

® TICKETS for KIDS Charities Frequently Asked Questions . WHO WE ARE: Tickets for Kids® Charities (TFK) was founded in 1994 to provide opportunities for low-income children to participate in events and activities routinely accessed by their more affluent peers. TFK has built networks of partnerships to provide tickets to children while enhancing capacity for the nonprofits serving them across the U.S. • HOW IT WORKS: TFK obtains donated tickets from individuals and venues and distributes the tickets through approved social service agency partners like Y programs, Boys & Girls Clubs, Big Brothers/Big Sisters and thousands of smaller grass-roots organizations and Title 1 schools serving low-income and at-risk children. All partner organizations are vetted, trained, and held to high standards of accountability. Tickets are distributed according to guidelines established by the ticket provider, i.e. e-tickets, letters of admission, or physical tickets at Will Call. • HOW MANY: Since its inception, TFK has distributed more than 3 million tickets valued in excess of $64.1 million to disadvantaged children and their families. In 2018, TFK distributed more than 194,000 tickets valued at over $6.6 million, and partnered with youth-serving organizations in 33 states. • WHO PAYS: TFK is donor funded and charges no fee for service. • HOW MUCH: TFK’s operating cost for each distributed ticket is approximately $4.00, which means an unforgettable experience for a child is provided for little more than the price of a cup of coffee. The average (retail) value of each TFK ticket is $36. Through the TFK model, a $1,000 gift generates 276 opportunities (tickets) valued at $36 each, or $8,832 in ticket value. -

Soccer Leagues

SOCCER LEAGUES {Appendix 5, to Sports Facility Reports, Volume 14} Research completed as of July 18, 2013 MAJOR INDOOR SOCCER LEAGUE (MISL) Team: Baltimore Blast Principal Owner: Edwin F. Hale, Sr. Current Value ($/Mil): N/A Team Website Stadium: 1st Mariner Arena Date Built: 1962 Facility Cost ($/Mil): N/A Facility Financing: N/A Facility Website UPDATE: The City of Baltimore is still looking to start a private-public partnership for a new 18,500-seat arena to replace the aging 1st Mariner Arena, which will cost around $500 million. Private funding would go towards the new stadium, while public funding would be used to build a convention center. In March 2012, the state legislature declined to give $2,500,000 for design proposals until a more firm commitment to the project from the City of Baltimore is verbalized. As of February 2013, no verbal commitment had been made. Throughout 2013, the arena will be celebrating its 50th year in existence. NAMING RIGHTS: Baltimore Blast owner and 1st Mariner Bank President and CEO Ed Hale acquired the naming rights to the arena through his company, Arena Ventures, LLC, as a result of a national competitive bidding process conducted by the City of Baltimore. Arena Ventures agreed to pay the City $75,000 annually for ten years for the naming rights, which started in 2003. © Copyright 2013, National Sports Law Institute of Marquette University Law School Page 1 Team: Milwaukee Wave Principal Owner: Jim Lindenberg Current Value ($/Mil): N/A Team Website Stadium: U.S. Cellular Arena Date Built: 1950 Facility Cost ($/Mil): 10 Facility Financing: N/A Facility Website Update: In June 2013, the University of Wisconsin–Milwaukee announced that it will return to the U.S. -

Comparison of Selected Governance and Operations Issues at Minnesota Sports Facilities

O L A Comparison of Selected Governance and Operations Issues at Minnesota Sports Facilities Special Review July 26, 2017 Office of the Legislative Auditor OFFICE OF THE LEGISLATIVE AUDITOR CENTENNIAL OFFICE BUILDING – SUITE 140 State of Minnesota 658 CEDAR STREET – SAINT PAUL, MN 55155 State of Minnesota Office of the Legislative Auditor Special Reviews We call this—and other reviews—“special” when they were not part of our regular schedule of audits and evaluations. We typically conduct a special review in response to an allegation that a person or organization has not used public resources in compliance with state law. While the focus of a special review is more narrow than an audit or evaluation, our objective is the same: to find the facts and report them accurately and objectively. We accept allegations from anyone, and we can keep the source confidential. For more information about the Office of the Legislative Auditor, go to our website at: www.auditor.leg.state.mn.us For more information about OLA and to access its reports, go to: www.auditor.leg.state.mn.us. To offer comments about our work or suggest an audit, evaluation, or special review, call 651-296-4708 or email [email protected]. To obtain printed copies of our reports or to obtain reports in electronic ASCII text, Braille, large print, or audio, call 651-296-4708. People with hearing or speech disabilities may call through Minnesota Relay by dialing 7-1-1 or 1-800-627-3529. Photo provided by the Minnesota Department of Administration with recolorization done by OLA. -

Visited on 3/1/2016

Minnesota - Wikipedia, the freevisited encyclopedia on 3/1/2016 Page 1 of 15 Coordinates: 46°N 94°W Minnesota From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Minnesota ( i/mɪnᵻˈsoʊtə/; locally [ˌmɪnəˈso̞ ɾə]) is a state in the Midwestern United States. State of Minnesota Minnesota was admitted as the 32nd state on May 11, 1858, created from the eastern half of the Minnesota Territory. The name comes from the Dakota word for "clear blue water".[5] Owing to its large number of lakes, the state is informally known as the "Land of 10,000 Lakes". Its official motto is L'Étoile du Nord (French: Star of the North). Minnesota is the 12th largest in area and the 21st most populous of the U.S. States; nearly 60 percent of its residents live in the Minneapolis –Saint Paul metropolitan area (known as the "Twin Cities"), the center of transportation, business, Flag Seal industry, education, and government and home to an internationally known arts community. The Nickname(s): Land of 10,000 Lakes; remainder of the state consists of western prairies now given over to intensive agriculture; North Star State; The Gopher State; The State of deciduous forests in the southeast, now partially cleared, farmed and settled; and the less populated Hockey. North Woods, used for mining, forestry, and recreation. Motto(s): L'Étoile du Nord (French: The Star of the North) Minnesota is known for its idiosyncratic social and political orientations and its high rate of civic participation and voter turnout. Until European settlement, Minnesota was inhabited by the Dakota and Ojibwe/Anishinaabe. The large majority of the original European settlers emigrated from Scandinavia and Germany, and the state remains a center of Scandinavian American and German American culture. -

O Montreal Canadiens Continua Invicto

A VOZ DE PORTUGAL LE PLUS ANCIEN JOURNAL DE LANGUE PORTUGAISE AU CANADA - DEPUIS 1961 1851 Ontario E. DIRECTEUR: MANUEL DE SEQUEIRA RODRIGUES 514.563.1211 ANO 56 | EDIÇÃO Nº24 | QUARTA-FEIRA, 26 DE OUTUBRO 2016 | WWW.AVOZDEPORTUGAL.COM | DISTRIBUIÇÃO GRATUITA NOSSA SENHORA DE FÁTIMA EM MONTREAL AZORES AIRLINES NO 11 SALÃO DO TURISMO E VIAGENS EM MONTREAL zores Airlines é a nova imagem na treal, conhecida como uma das maiores Adiáspora. Azores Airlines, as asas exposições(feiras) de turismo e viagens dos Açores, a ligação dos Açores ao Ca- no mundo. nadá e do Canadá aos Açores. Sexta- O balcão foi inaugurado pelo Presidente -feira foi a inauguração do balcão no Eng. Paulo Menezes acompanhado pelo Salão do Turismo e Viagens que decor- Diretor Executivo da Associação de Tu- HOMENAGEM A UMA GRANDE reu nos dias 21, 22 e 23 de outubro na rismo dos Acores Dr. Francisco Coelho, ENHORA LVIRA DE OUSA grande sala de Exposição da Place Bo- Diretor no Canadá Carlos Botelho, Diretor S , E S naventure no centro da cidade de Mon- Continuação na página 5 7 Globex Portuguese add.pdf 1 8/17/2016 1:54:19 PM C CASA DE CÂMBIO Atenção: se não tem selo da Mosti M Mondiale é porque não é Mosti Mondiale Converter antes de partir… Servico de análise do seu vinho Y MOSTO CLASSICO Westmount Succursale Principale 1336 Ave. Greene H3Z 2B1 ruby Cabernet, 42 variedades de * Carrignane, Merlot, mosto à sua escolha CM $ Che e Mais * Montréal Centre-ville 2090 Ave. Union H3A 2C2 Cada grena MY 46 * Montréal Quartier Des Spectacles 455 St. -

Comparison of Selected Governance and Operations Issues at Minnesota Sports Facilities

This document is made available electronically by the Minnesota Legislative Reference Library as part of an ongoing digital archiving project. http://www.leg.state.mn.us/lrl/lrl.asp O L A Comparison of Selected Governance and Operations Issues at Minnesota Sports Facilities Special Review July 26, 2017 Office of the Legislative Auditor OFFICE OF THE LEGISLATIVE AUDITOR CENTENNIAL OFFICE BUILDING – SUITE 140 State of Minnesota 658 CEDAR STREET – SAINT PAUL, MN 55155 State of Minnesota Office of the Legislative Auditor Special Reviews We call this—and other reviews—“special” when they were not part of our regular schedule of audits and evaluations. We typically conduct a special review in response to an allegation that a person or organization has not used public resources in compliance with state law. While the focus of a special review is more narrow than an audit or evaluation, our objective is the same: to find the facts and report them accurately and objectively. We accept allegations from anyone, and we can keep the source confidential. For more information about the Office of the Legislative Auditor, go to our website at: www.auditor.leg.state.mn.us For more information about OLA and to access its reports, go to: www.auditor.leg.state.mn.us. To offer comments about our work or suggest an audit, evaluation, or special review, call 651-296-4708 or email [email protected]. To obtain printed copies of our reports or to obtain reports in electronic ASCII text, Braille, large print, or audio, call 651-296-4708. People with hearing or speech disabilities may call through Minnesota Relay by dialing 7-1-1 or 1-800-627-3529. -

AUBREY and the THREE MIGOS TOUR’ with SPECIAL GUESTS MIGOS – Tickets for New Dates on Sale to the General Public Starting Friday, June 15 at Ticketmaster.Com –

PLATINUM SELLING ARTIST DRAKE ADDS 11 MORE SHOWS TO THE ‘AUBREY AND THE THREE MIGOS TOUR’ WITH SPECIAL GUESTS MIGOS – Tickets For New Dates On Sale to the General Public Starting Friday, June 15 at Ticketmaster.com – LOS ANGELES, CA (June 11, 2018) – Platinum selling artist Drake is adding even more dates to his hotly anticipated ‘Aubrey and The Three Migos Tour’ kicking off July 26 in Salt Lake City. The outing, featuring special guests and “Walk It Talk It” collaborators Migos, is bringing 11 more shows to cities across North America, including New York dates at Madison Square Garden and Barclays Center, Los Angeles, Montreal, Boston, Houston, and more. The full list of routing can be found below. Produced by Live Nation, Drake’s tour will launch following the release of his hit singles “God’s Plan” and “Nice For What,” and after the release of his upcoming fifth studio album Scorpion. American Express® Card Members can purchase tickets for the newly added dates before the general public beginning Tuesday, June 12 at 12pm local time through Thursday, June 14 at 10pm local time. Tickets for the new dates go on sale to the general public Friday, June 15 at Ticketmaster.com starting at 12pm local time. AUBREY AND THE THREE MIGOS TOUR DATES *Newly Added Dates in Bold Thu Jul 26 Salt Lake City, UT Vivint Smart Home Arena Sat Jul 28 Denver, CO Pepsi Center Sun Jul 29 Denver, CO Pepsi Center Tue Jul 31 Kansas City, MO Sprint Center Wed Aug 01 St. Paul, MN Xcel Energy Center Fri Aug 10 Toronto, ON Air Canada Centre Sat Aug 11 Toronto, ON Air -

Worldwide Ticket Sales TOP 200 ARENA VENUES 1-100

2015 3Q YTD Worldwide Ticket Sales TOP 200 ARENA VENUES 1-100 1 1,235,033 The O2 - London London, UNITED KINGDOM 51 207,229 Allphones Arena Sydney, AUSTRALIA 2 824,381 Manchester Arena Manchester, UNITED KINGDOM 52 204,932 Amway Center Orlando, FL 3 667,322 The SSE Hydro Glasgow, UNITED KINGDOM 53 204,782 Target Center Minneapolis, MN 4 595,954 Arena Ciudad De Mexico Mexico City, MEXICO 54 197,865 Oracle Arena Oakland, CA 5 576,768 Madison Square Garden Arena New York, NY 55 192,872 Moda Center Portland, OR 6 504,153 Bridgestone Arena Nashville, TN 56 190,192 Qantas Credit Union Arena Darling Harbour, AUSTRALIA 7 483,820 Ziggo Dome Amsterdam, NETHERLANDS 57 189,131 Chesapeake Energy Arena Oklahoma City, OK 8 468,622 Lanxess Arena Cologne, GERMANY 58 187,699 Vector Arena Auckland, NEW ZEALAND 9 431,754 Staples Center Los Angeles, CA 59 185,561 United Center Chicago, IL 10 423,709 Forum Inglewood, CA 60 178,302 Tempodrom Berlin, GERMANY 11 418,436 Allstate Arena Rosemont, IL 61 177,989 Brisbane Entertainment Centre Brisbane, AUSTRALIA 12 417,431 Barclays Center Brooklyn, NY 62 177,979 Antwerps Sportpaleis Merksem, BELGIUM 13 405,448 American Airlines Center Dallas, TX 63 177,976 Ticketpro Dome Johannesburg, SOUTH AFRICA 14 404,094 Bell Centre Montreal, CANADA 64 175,255 TD Garden Boston, MA 15 365,693 Sprint Center Kansas City, MO 65 165,758 Ericsson Globe Stockholm, SWEDEN 16 363,383 Arena Monterrey Monterrey, MEXICO 66 164,986 Honda Center Anaheim, CA 17 357,636 Philips Arena Atlanta, GA 67 163,406 AmericanAirlines Arena Miami, FL 18 -

Examining the Evolution of Urban Multipurpose Facilities

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School July 2019 Examining the Evolution of Urban Multipurpose Facilities: Applying the Ideal-Type to the Facilities of the National Hockey League and National Basketball Association Benjamin Downs Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the Other Kinesiology Commons, and the Sports Studies Commons Recommended Citation Downs, Benjamin, "Examining the Evolution of Urban Multipurpose Facilities: Applying the Ideal-Type to the Facilities of the National Hockey League and National Basketball Association" (2019). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 4989. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/4989 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. EXAMINING THE EVOLUTION OF URBAN MULTIPURPOSE FACILITIES: APPLYING THE IDEAL-TYPE TO THE FACILITIES OF THE NATIONAL HOCKEY LEAGUE AND NATIONAL BASKETBALL ASSOCIATION A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of Kinesiology by Benjamin Downs B.A., The College of Wooster, 2008 M.S., Mississippi State University, 2016 August 2019 This dissertation is dedicated to my daughter Stella Corinne. Thank you for being my source of inspiration and provider of levity throughout this process. I love you Birdie. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS First and foremost, I would like to thank my doctoral advisor, Dr. -

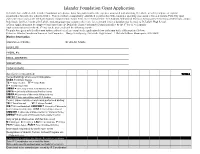

Islander Foundation Grant Application

Islander Foundation Grant Application DeLaSalle has established the Islander Foundation to help raise funds for grants to offset the expenses associated with attending DeLaSalle, or to help improve or expand opportunities for particular school activities. This is a volunteer opportunity established in partnership with companies operating concession services at various Twin City sport and event venues such as the US Bank Stadium, Target Center, Target Field, Xcel Energy Center, TCF Stadium, Williams & Mariucci Arenas on the University of Minnesota campus. Individuals, families, friends or DeLaSalle students/groups may volunteer their time for events and in turn a donation may be made to DeLaSalle High School. A Grant Application must be completed and turned into the DeLaSalle Finance or Islander Foundation office by the 8th day of each month. Applications not turned in by the 8th may not be processed until the following month. To apply for a grant to help offset your tuition and/or fees, please complete the application below and return to the address printed below: Return to: Islander Foundation/Financial Aid Committee – Douge Schildgen @ DeLaSalle High School – 1 DeLaSalle Drive Minneapolis, MN 55401 Worker Information VOLUNTEER NAME: STUDENT NAME: ADDRESS: PHONE #'s: EMAIL ADDRESS: SIGNATURE: TODAYS DATE: Date(s) of events worked TOTALS Venue(building) where event took place: USBS = US Bank Stadium TC = Target Center TF = Target Field X = Xcel Energy Center UMMA = University of Minnesota Mariucci Arena UMPA = University of Minnesota Pavillion Arena UMWA = University of Minnesota William's Arena UMTCF = University of Minnesota TCF Stadium Team / Game volunteer work was performed during: TB = Twins Baseball VF = Vikings Football WB = Wolves Basketball, UMM/WB = University of Minnesota Men's / Women's Basketball, C/SE = Concert/Special Event UMM/WH = University of Minnesota Men's / Women's Hockey UMMGF = University of Minnesota Men’s Gopher Football Duty of job performed on shift for this event.