THE ABSOLUTE OR SELF Science and the Absolute

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

In the Name of Krishna: the Cultural Landscape of a North Indian Pilgrimage Town

In the Name of Krishna: The Cultural Landscape of a North Indian Pilgrimage Town A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA BY Sugata Ray IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Frederick M. Asher, Advisor April 2012 © Sugata Ray 2012 Acknowledgements They say writing a dissertation is a lonely and arduous task. But, I am fortunate to have found friends, colleagues, and mentors who have inspired me to make this laborious task far from arduous. It was Frederick M. Asher, my advisor, who inspired me to turn to places where art historians do not usually venture. The temple city of Khajuraho is not just the exquisite 11th-century temples at the site. Rather, the 11th-century temples are part of a larger visuality that extends to contemporary civic monuments in the city center, Rick suggested in the first class that I took with him. I learnt to move across time and space. To understand modern Vrindavan, one would have to look at its Mughal past; to understand temple architecture, one would have to look for rebellions in the colonial archive. Catherine B. Asher gave me the gift of the Mughal world – a world that I only barely knew before I met her. Today, I speak of the Islamicate world of colonial Vrindavan. Cathy walked me through Mughal mosques, tombs, and gardens on many cold wintry days in Minneapolis and on a hot summer day in Sasaram, Bihar. The Islamicate Krishna in my dissertation thus came into being. -

Collected Works of Ananda K Coomaraswamy Series

A. Collected Works of Ananda K. Coomaraswamy Philosophical Writings TIME AND ETERNITY Ananda K.Coomaraswamy 1990, viii+107 pp. bib., ref., index ISBN: 81-85503-00-1: Rs 110 (HB) Man's awareness of Time has been articulated in ancient and modern civilizations through cosmologies, metaphysics, philosophy, religion, theology and the arts. Coomaraswamy propounds that though we live in Time, our deliverance lies in eternity. All religions make this distinction between what is merely "everlasting" (or "perpetual") and what is eternal. To probe into this mystery Coomaraswamy provides us with a detailed account of the teachings of each of the main world religions. Present edition embodies all marginal corrections which Coomaraswamy made on the first edition published during 1947 in Ascona, Switzerland. SPIRITUAL AUTHORITY AND TEMPORAL POWER IN THE INDIAN THEORY OF GOVERNMENT Ananda K.Coomaraswamy Edited by Keshavram N. Iyengar and Rama P.Coomaraswamy 1993, x+127pp. notes., ref., ISBN: 0-19-5631-43-9: Rs 200 (HB) 2013, xii+135pp., ISBN 13 : 978-81-246-0734-3 RsÊ.360 (HB) (reprint). The Indian theory of government is expounded in this work on the basis of the textual sources, mainly of the Brāhmaṇas and te Ṛgveda. The mantra from the Aitareya Brāhmaṇa (VIII.27) by which the priest addresses the king, spells out the relation between the spiritual and the temporal power. This "marriage formula" has its analogous applications in the cosmic, political, family and individual spheres of operation, in each by the conjunction of complementary agencies. The welfare of the community in each case depends upon a succession of obediences and loyalties; that of the subjects to the dual control of king and priest, that of the king to the priest, and that of all to the principle of an eternal law (dharma) as king of kings. -

John Cage's Entanglement with the Ideas Of

JOHN CAGE’S ENTANGLEMENT WITH THE IDEAS OF COOMARASWAMY Edward James Crooks PhD University of York Music July 2011 John Cage’s Entanglement with the Ideas of Coomaraswamy by Edward Crooks Abstract The American composer John Cage was famous for the expansiveness of his thought. In particular, his borrowings from ‘Oriental philosophy’ have directed the critical and popular reception of his works. But what is the reality of such claims? In the twenty years since his death, Cage scholars have started to discover the significant gap between Cage’s presentation of theories he claimed he borrowed from India, China, and Japan, and the presentation of the same theories in the sources he referenced. The present study delves into the circumstances and contexts of Cage’s Asian influences, specifically as related to Cage’s borrowings from the British-Ceylonese art historian and metaphysician Ananda K. Coomaraswamy. In addition, Cage’s friendship with the Jungian mythologist Joseph Campbell is detailed, as are Cage’s borrowings from the theories of Jung. Particular attention is paid to the conservative ideology integral to the theories of all three thinkers. After a new analysis of the life and work of Coomaraswamy, the investigation focuses on the metaphysics of Coomaraswamy’s philosophy of art. The phrase ‘art is the imitation of nature in her manner of operation’ opens the doors to a wide- ranging exploration of the mimesis of intelligible and sensible forms. Comparing Coomaraswamy’s ‘Traditional’ idealism to Cage’s radical epistemological realism demonstrates the extent of the lack of congruity between the two thinkers. In a second chapter on Coomaraswamy, the extent of the differences between Cage and Coomaraswamy are revealed through investigating their differing approaches to rasa , the Renaissance, tradition, ‘art and life’, and museums. -

European Imperialism

Quotes Basics Science History Social Other Search h o m e e u r o p e a n i m p e r i a l i s m c o n t e n t s Hinduism remains a vibrant, cultural and religious force in the world today. To understand Hinduism, it is necessary that we examine its history and marvel at its sheer stamina to survive in spite of repeated attacks across India's borders, time and again, by Greeks, Shaks, Huns, Arabs, Pathans, Mongols, Portuguese, British etc. India gave shelter, acceptance, and freedom to all. But, in holy frenzy, millions of Hindus were slaughtered or proselytized. Their cities were pillaged and burnt, temples were destroyed and accumulated treasures of centuries carried off. Even under grievous persecutions from the ruling foreigners, the basics of its civilization remained undefiled and, as soon as the crises were over Hindus returned to the same old ways of searching for the perfection or the unknown. Introduction The history of what is now India stretches back thousands of years, further than that of nearly any other region on earth. Yet, most historical work on India concentrates on the period after the arrival of Europeans, with predictable biases, distortions, and misapprehensions. Many overviews of Indian history offer a few cursory opening chapters that take the reader from Mohenjo-daro to the arrival of the Moghuls and the Europeans. India's history is ancient and abundant. The profligacy of monuments so testifies it and so does a once-lost civilization, the Harappan in the Indus valley, not to mention the annals commissioned by various conquerors. -

The Mountain Path

THE MOUNTAIN PATH Arunachala! Thou dost root out the ego of those who meditate on Thee in the heart, Oh Arunachala! Fearless I seek Thee, Fearlessness Itself! How canst Thou fear to take me, O Arunachala ? (A QUARTERLY) — Th$ Marital Garland " Arunachala ! Thou dost root out the ego of those who of Letters, verse 67 meditate on Thee in the heart, Oh Arunachala! " — The Marital Garland of Letters, verse 1. Publisher : T. N. Venkataraman, President, Board of Trustees, Vol. 17 JULY 1980 No. Ill Sri Ramanasramam, Tiruvannamalai. * CONTENTS Page Editorial Board : EDITORIAL: The Journey Inward .. 127 Prof. K. Swaminathan The Nature and Function of the Guru Sri K. K. Nambiar —Arthur Osborne .. 129 Mrs. Lucy Cornelssen Bhagavan's Father .. 134 Smt. Shanta Rungachary Beyond Thought — Dr. K. S. Rangappa .. 136 Dr. K. Subrahmanian Mind and Ego — Dr. M. Sadashiva Rao .. 141 Sri Jim Grant Suri Nagamma — Joan Greenblatt .. 144 Sri David Godman A Deeply Effective Darshan of Bhagavan — /. D. M. Stuart and O. Raumer-Despeigne .. 146 God and His Names — K. Subrahmanian .. 149 Religions or Philosophy? — K. Ramakrishna Rao . 150 Managing Editor: The Way to the Real — A. T. Millar .. 153 V. Ganesan, Song of At-One-Ment — (IV) Sri Ramanasramam, — K. Forrer .. 155 Tiruvannamalai Scenes from Ramana's Life — (III) — B. V. Narasimha Swamy .. 159 * Transfiguration — Mary Casey .. 162 Garland of Guru's Sayings — Sri Muruganar Annual Subscription Tr. by Professor K. Swaminathan .. 163 INDIA Rs. 10 Reintegration, Part II, Awareness — Wei Wu Wei 165 FOREIGN £ 2.00 $ 4.00 Ramana Maharshi and How not to Grow Life Subscription : Old — Douglas Harding . -

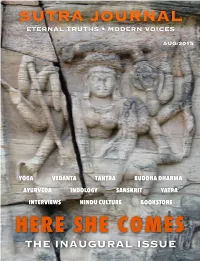

The Inaugural Issue Sutra Journal • Aug/2015 • Issue 1

SUTRA JOURNAL ETERNAL TRUTHS • MODERN VOICES AUG/2015 YOGA VEDANTA TANTRA BUDDHA DHARMA AYURVEDA INDOLOGY SANSKRIT YATRA INTERVIEWS HINDU CULTURE BOOKSTORE HERE SHE COMES THE INAUGURAL ISSUE SUTRA JOURNAL • AUG/2015 • ISSUE 1 Invocation 2 Editorial 3 What is Dharma? Pankaj Seth 9 Fritjof Capra and the Dharmic worldview Aravindan Neelakandan 15 Vedanta is self study Chris Almond 32 Yoga and four aims of life Pankaj Seth 37 The Gita and me Phil Goldberg 41 Interview: Anneke Lucas - Liberation Prison Yoga 45 Mantra: Sthaneshwar Timalsina 56 Yatra: India and the sacred • multimedia presentation 67 If you meet the Buddha on the road, kill him Vikram Zutshi 69 Buddha: Nibbana Sutta 78 Who is a Hindu? Jeffery D. Long 79 An introduction to the Yoga Vasistha Mary Hicks 90 Sankalpa Molly Birkholm 97 Developing a continuity of practice Virochana Khalsa 101 In appreciation of the Gita Jeffery D. Long 109 The role of devotion in yoga Bill Francis Barry 113 Road to Dharma Brandon Fulbrook 120 Ayurveda: The list of foremost things 125 Critics corner: Yoga as the colonized subject Sri Louise 129 Meditation: When the thunderbolt strikes Kathleen Reynolds 137 Devata: What is deity worship? 141 Ganesha 143 1 All rights reserved INVOCATION O LIGHT, ILLUMINATE ME RG VEDA Tree shrine at Vijaynagar EDITORIAL Welcome to the inaugural issue of Sutra Journal, a free, monthly online magazine with a Dharmic focus, fea- turing articles on Yoga, Vedanta, Tantra, Buddhism, Ayurveda, and Indology. Yoga arose and exists within the Dharma, which is a set of timeless teachings, holistic in nature, covering the gamut from the worldly to the metaphysical, from science to art to ritual, incorporating Vedanta, Tantra, Bud- dhism, Ayurveda, and other dimensions of what has been brought forward by the Indian civilization. -

By Ananda K. Coomaraswamy

From the World Wisdom online library: www.worldwisdom.com/public/library/default.aspx THE VEDANTA AND WESTERN TRADITION* Ananda Coomaraswamy These are really the thoughts of all men in all ages and lands, they are not original with me. Walt Whitman I There have been teachers such as Orpheus, Hermes, Buddha, Lao tzu, and Christ, the historicity of whose human existence is doubtful, and to whom there may be accorded the higher dignity of a mythical reality. Shankara, like Plotinus, Augustine, or Eckhart, was certainly a man among men, though we know comparatively little about his life. He was of south Indian Brahman birth, flourished in the first half of the ninth century A.D., and founded a monastic order which still survives. He became a samnyasin, or “truly poor man,” at the age of eight, as the disciple of a certain Govinda and of Govinda’s own teacher Gaudapada, the author of a treatise on the Upanisads in which their essential doctrine of the non-duality of the divine Being was set forth. Shankara journeyed to Benares and wrote the famous commentary on the Brahma Sutra there in his twelfth year; the commentaries on the Upanisads and Bhagavad Gita were written later. Most of the great sage’s life was spent wandering about India, teaching and taking part in controversies. He is understood to have died between the ages of thirty and forty. Such wanderings and disputations as his have always been characteristically Indian institutions; in his days, as now, Sanskrit was the lingua franca of learned men, just as for centuries Latin was the lingua franca of Western countries, and free public debate was so generally recognized that halls erected for the accommodation of peri patetic teachers and disputants were at almost every court. -

Sankara's Doctrine of Maya Harry Oldmeadow

The Matheson Trust Sankara's Doctrine of Maya Harry Oldmeadow Published in Asian Philosophy (Nottingham) 2:2, 1992 Abstract Like all monisms Vedanta posits a distinction between the relatively and the absolutely Real, and a theory of illusion to explain their paradoxical relationship. Sankara's resolution of the problem emerges from his discourse on the nature of maya which mediates the relationship of the world of empirical, manifold phenomena and the one Reality of Brahman. Their apparent separation is an illusory fissure deriving from ignorance and maintained by 'superimposition'. Maya, enigmatic from the relative viewpoint, is not inexplicable but only not self-explanatory. Sankara's exposition is in harmony with sapiential doctrines from other religious traditions and implies a profound spiritual therapy. * Maya is most strange. Her nature is inexplicable. (Sankara)i Brahman is real; the world is an illusory appearance; the so-called soul is Brahman itself, and no other. (Sankara)ii I The doctrine of maya occupies a pivotal position in Sankara's metaphysics. Before focusing on this doctrine it will perhaps be helpful to make clear Sankara's purposes in elaborating the Advaita Vedanta. Some of the misconceptions which have afflicted English commentaries on Sankara will thus be banished before they can cause any further mischief. Firstly, Sankara should not be understood or approached as a 'philosopher' in the modern Western sense. Ananda Coomaraswamy has rightly insisted that, The Vedanta is not a philosophy in the current sense of the word, but only as it is used in the phrase Philosophia Perennis... Modern philosophies are closed systems, employing the method of dialectics, and taking for granted that opposites are mutually exclusive. -

A. K. Coomaraswamy and R. Guénon

From the World Wisdom online library: www.worldwisdom.com/public/library/default.aspx Prologue A Fateful Meeting of Minds: A. K. Coomaraswamy and R. Guénon by Marco Pallis Memories of the great man whose centenary we are now wishing to celebrate go back, for me, to the late 1920s, when I was studying music under Arnold Dolmetsch whose championship of ancient musical styles and methods in Western Europe followed lines which Coomaraswamy, whom he had known personally, highly approved of, as reflecting many of his own ideas in a particular field of art. Central to Dolmetsch’s thinking was his radical rejection of the idea of “progress,” as applied to the arts, at a time when the rest of the musical profession took this for granted. The earlier forms of music which had disappeared from the European scene together with the instruments for which that music was composed must, so it was argued, have been inferior or “primitive” as the saying went; speak ing in Darwinian terms their elimination was part of the process of natural selection whereby what was more limited, and therefore by comparison less satisfying to the modern mind, became outmoded in favor of what had been rendered possible through the general advance of mankind. All the historical and psychological contradic tions implied in such a world-view were readily bypassed by a socie ty thinking along these lines; inconvenient evidence was simply brushed aside or else explained away by means of palpably tenden tious arguments. Such was the climate of opinion at the beginning of the present century: if belief in the quasi-inevitable march of progress is nowadays beginning to wear rather thin, this is largely due to the results of two world-wars and to the threats of mass- destruction which progress in the technological field has inevitably brought with it. -

Seeing with Two Eyes René Guénon, Ananda Coomaraswamy and the Complementary Reassertion of Traditional Metaphysics

Seeing with Two Eyes René Guénon, Ananda Coomaraswamy and the Complementary Reassertion of Traditional Metaphysics by Peter Samsel Sacred Web 18 (2007), pp.119-54. “Not that the One is two, but that these two are one.” Hermes Trismegistos One of the most remarkable, if unremarked intellectual and spiritual developments of the last century has been that of a school of thought concerned with the reassertion at once of tradition and of the sacred. Termed the Traditionalist, or Perennialist School,1 its overarching themes might best be summarized in the subtitle both of its foremost journal and seminal anthology:2 Metaphysics, Cosmology, Tradition, Symbolism. Although comprised of diverse figures, its coherence has been readily apparent: as Kenneth Oldmeadow has observed, Anyone who has given more than cursory attention to the writings of these men will not doubt that they form a unified group. They share philosophical assumptions and adhere to a specific understanding of the perennial philosophy. Their works are shot through with the same ideas, principles and themes. The solidarity of the group is evident not only in the substance of their writings but in several superficial and more immediately obvious ways….Doubtless there are many other reciprocal relationships, personal and intellectual, which are not visible to the public eye.3 The Traditionalist School may be understood in perhaps three conjoined ways: first, as a collection of diverse contemporary writers united under the banner of a common spiritual vision of tradition; second, as a continuation and reaffirmation in the contemporary era of a ‘golden chain’ of expression of the philosophia perennis et universalis4 extending across civilizations and through history; third, as a decisive doctrinal assertion and theoria of the Real, of That which is, along with the historic and normative human adumbrations consequent upon It. -

Perspectives by Whithall N

From the online Library at: http://www.frithjofschuon.info Perspectives by Whithall N. Perry Source: Sophia, Vol. 4, No. 2, 1998 The intellect of the wise man is always with divinity. Sextus the Pythagorean t all began for my wife and myself in October 1946, in that least likely of settings—the Alexandria port jail. This was just after the War, when Frithjof Schuon had hardly I commenced his writing; but thanks largely to the works of René Guénon and Ananda Coomaraswamy, the two of us were already heading East, in a battle-scarred world where boats and visas were almost impossible to come by, in search of spiritual wisdom. We were preceded to Egypt by an American friend whose youthful enthusiasm had spurred our ambition even while compromising his own. He had obtained passage as seaman on a freighter, and he celebrated his arrival in the world of Islam by jumping ship, throwing his Western clothes into the harbor of Alexandria, donning a jellaba and passing the night in the great mosque before proceeding without visa the next day to Cairo, where he ingratiated himself into the Guénon household. It was only some weeks later when the odd appearance of this black- bearded stranger, in a gallabiyah of Guénon’s so long it dragged on the pavement, and sporting an Afghan astrakhan rare in Cairo, caught the attention of the police and brought this idyll to a close. We had just left our ship, the former Italian luxury liner “Vulcania”—little more now than a battered transport—and were standing in the midst of the postwar pandemonium of the waterfront waiting for the unloading of the large crate of books that was our sole possession, when an urchin thrust a note into my defensive fist. -

Article Collected Works of Dr. Ananda K. Coomaraswamy

ARTICLE Published in Vihangama 2001 Vol. II (February - March) COLLECTED WORKS OF DR. ANANDA K. COOMARASWAMY DR. LALIT M. GUJRAL The Kalasamalocana programme of the Kalakosa Division of the IGNCA relates to publications on critical writings on different facets of the arts and aesthetics. While one part of the series concentrates on works of eminent scholars who have dealt with the fundamental concepts, identified perennial sources and created bridges of communication by juxtaposing diverse traditions; the other part deals with revision and re-arranged editions and translations of a select number of eminent authors and their works. The most important part of this programme is to bring out the Collected Works of Dr. Ananda Coomaraswamy, reorganised thematically and with the author's authentic revisions, edited by eminent scholars, in about 30 volumes. Through his writings, Ananda Coomaraswamy (1877-1947) revealed himself as a great art critic, philosopher and historian of our time. In the words of his wife, Dona Luisa, "The extraordinary production in art history, aesthetic theory, social criticism, comparative religion, symbolism and metaphysics of this man is astounding. He had intellectual powers with which few men of his generation could compare". Besides being an enlightening influence in the West, he was also instrumental in the East's awakening to the beauty of its own tradition. Coomaraswamy's publications comprise many voluminous books, and a very large range of pamphlets, articles, critical reviews, translations and letters published in different countries. Indeed, a glance at the list of his writings would make one wonder whether one is looking through the Catalogue of a Library or the works of a single individual.