TURNUS and TERMINUS in AENEID 12 in the Effort to Determine

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Plato Apology of Socrates and Crito

COLLEGE SERIES OF GREEK AUTHORS EDITED UNDER THE SUPERVISION OF JOHN WILLIAMS WHITE, LEWIS R. PACKARD, a n d THOMAS D. SEYMOUR. PLATO A p o l o g y o f S o c r a t e s AND C r i t o EDITED ON THE BASIS OF CRON’S EDITION BY LOUIS DYER A s s i s t a n t ·Ρι;Οχ'ε&^ο^ ι ν ^University. BOSTON: PUBLISHED BY GINN & COMPANY. 1902. I P ■ C o p · 3 Entered, according to Act of Congress, in the year 1885, by J o h n W il l ia m s W h i t e a n d T h o m a s D. S e y m o u r , In the Office of the Librarian of Congress, at Washington. J . S. C u s h in g & Co., P r i n t e r s , B o s t o n . PREFACE. T his edition of the Apology of Socrates and the Crito is based upon Dr. Christian Cron’s eighth edition, Leipzig, 1882. The Notes and Introduction here given have in the main been con fined within the limits intelligently drawn by Dr. Cron, whose commentaries upon various dialogues of Plato have done and still do so much in Germany to make the study of our author more profitable as well as pleasanter. No scruple has been felt, how ever, in making changes. I trust there are few if any of these which Dr. Cron might not himself make if he were preparing his work for an English-thinking and English-speaking public. -

Hippocrates in Context Studies in Ancient Medicine

HIPPOCRATES IN CONTEXT STUDIES IN ANCIENT MEDICINE EDITED BY JOHN SCARBOROUGH PHILIP J. VAN DER EIJK ANN HANSON NANCY SIRAISI VOLUME 31 HIPPOCRATES IN CONTEXT Papers read at the XIth International Hippocrates Colloquium University of Newcastle upon Tyne 27–31 August 2002 EDITED BY PHILIP J. VAN DER EIJK BRILL LEIDEN • BOSTON 2005 Cover illustration: Late fifteenth-century portrait of Hippocrates sitting, reading. Behind him, two standing philosophers dispute (Wellcome Library, London). This book is printed on acid-free paper. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data A C.I.P. record for this book is available from the Library of Congress. ISSN 0925–1421 ISBN 90 04 14430 7 © Copyright 2005 by Koninklijke Brill NV, Leiden, The Netherlands All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, translated, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior written permission from the publisher. Authorization to photocopy items for internal or personal use is granted by Brill provided that the appropriate fees are paid directly to The Copyright Clearance Center, 222 Rosewood Drive, Suite 910 Danvers MA 01923, USA. Fees are subject to change. printed in the netherlands CONTENTS Preface ........................................................................................ ix Acknowledgements ...................................................................... xiii Abbreviations ............................................................................. -

Thucydides HISTORY of the PELOPONNESIAN WAR

Thucydides HISTORY OF THE PELOPONNESIAN WAR Thucydides HISTORY OF THE PELOPONNESIAN WAR ■ HISTORY OF THE PELOPONNESIAN WAR file:///D|/Documenta%20Chatolica%20Omnia/99%20-%20Provvisori/mbs%20Library/001%20-Da%20Fare/00-index.htm2006-06-01 15:02:55 Thucydides HISTORY OF THE PELOPONNESIAN WAR:Index. Thucydides HISTORY OF THE PELOPONNESIAN WAR General Index ■ THE FIRST BOOK ■ THE SECOND BOOK ■ THE THIRD BOOK ■ THE FOURTH BOOK ■ THE FIFTH BOOK ■ THE SIXTH BOOK ■ THE SEVENTH BOOK ■ THE EIGHTH BOOK file:///D|/Documenta%20Chatolica%20Omnia/99%20-%20Provvisori/mbs%20Library/001%20-Da%20Fare/0-PeloponnesianWar.htm2006-06-01 15:02:55 PELOPONNESIANWAR: THE FIRST BOOK, Index. THE FIRST BOOK Index CHAPTER I. The State of Greece from the earliest Times to the Commencement of the Peloponnesian War CHAPTER II. Causes of the War - The Affair of Epidamnus - The Affair of Potidaea CHAPTER III. Congress of the Peloponnesian Confederacy at Lacedaemon CHAPTER IV. From the end of the Persian to the beginning of the Peloponnesian War - The Progress from Supremacy to Empire CHAPTER V. Second Congress at Lacedaemon - Preparations for War and Diplomatic Skirmishes - Cylon - Pausanias - Themistocles file:///D|/Documenta%20Chatolica%20Omnia/99%20-%20Provvi...i/mbs%20Library/001%20-Da%20Fare/1-PeloponnesianWar0.htm2006-06-01 15:02:55 PELOPONNESIANWAR: THE SECOND BOOK, Index. THE SECOND BOOK Index CHAPTER VI. Beginning of the Peloponnesian War - First Invasion of Attica - Funeral - Oration of Pericles CHAPTER VII. Second Year of the War - The Plague of Athens - Position and Policy of Pericles - Fall of Potidaea CHAPTER VIII. Third Year of the War - Investment of Plataea - Naval Victories of Phormio - Thracian Irruption into Macedonia under Sitalces file:///D|/Documenta%20Chatolica%20Omnia/99%20-%20Provvi...i/mbs%20Library/001%20-Da%20Fare/1-PeloponnesianWar1.htm2006-06-01 15:02:55 PELOPONNESIANWAR: THE THIRD BOOK, Index. -

The Persian Bird's Conquest

Cahn’s Quarterly 1/2020 Recipe from Antiquity The Persian Bird’s Conquest By Yvonne Yiu bustle that ensues following his cry: “When he sings his song of dawning everybody jumps out of bed – smiths, potters, tanners, cobblers, bathmen, corn-dealers, lyre-turning shield-makers; the men put on their shoes and go out to work although it is not yet light.” (Arist., Birds 488-92). Furthermore, cocks fulfilled a number of symbolic and ritual functions, for instance as sacrificial an- imals or as love tokens from the adult male (erastes) to the younger male (eromenos). Not least, cockfighting was a very popular sport. However, the “Persian bird’s" actual con- quest, which enabled it to become the most common bird in the world with a current population estimated at around 23 billion by the FAO, paradoxically did not begin until it found a place on the dinner menu. It is difficult to determine when, exactly, Picentine bread and sala cattabia Apiciana on A PLATE. Clay. Dm. 26 cm. Roman, 3rd-5th cent. A.D. CHF 3,200. A GRATER. Bronze. L. 14 cm. Etruscan, 5th-3rd cent. B.C. CHF 1,800. A KNIFE. Bronze, iron. L. 14.7 cm. Roman, chicken eggs and meat became a significant 1st-3rd cent. A.D. CHF 1,800. A SPOON. Silver. L. 9.5 cm. Roman, 2nd-4th cent. A.D. CHF 2,800. nutritional factor in the Mediterranean. An- drew Dalby assumes that in the course of “Those were terrible times for the Athenians. native to Southeast Asia. The earliest conclu- the Classical Period chickens rapidly sup- The fleet had been lost in the Sicilian Expe- sive evidence of domestication comes from planted the less productive goose, which dition, Lamachos was no longer, Nikias was the Bronze Age Indus Culture and dates from had been the farmyard egg-layer in Greece dead, the Lacedaemonians besieged Attica," ca. -

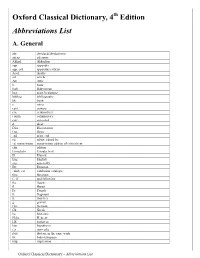

Abbreviations List A

Oxford Classical Dictionary, 4th Edition Abbreviations List A. General abr. abridged/abridgement adesp. adespota Akkad. Akkadian app. appendix app. crit. apparatus criticus Aeol. Aeolic art. article Att. Attic b. born Bab. Babylonian beg. at/nr. beginning bibliog. bibliography bk. book c. circa cent. century cm. centimetre/s comm. commentary corr. corrected d. died Diss. Dissertation Dor. Doric end at/nr. end ed. editor, edited by ed. maior/minor major/minor edition of critical text edn. edition Einzelschr. Einzelschrift El. Elamite Eng. English esp. especially Etr. Etruscan exhib. cat. exhibition catalogue fem. feminine f., ff. and following fig. figure fl. floruit Fr. French fr. fragment ft. foot/feet g. gram/s Ger. German Gk. Greek ha. hectare/s Hebr. Hebrew HS sesterces hyp. hypothesis i.a. inter alia ibid. ibidem, in the same work IE Indo-European imp. impression Oxford Classical Dictionary – Abbreviations List in. inch/es introd. introduction Ion. Ionic It. Italian kg. kilogram/s km. kilometre/s lb. pound/s l., ll. line, lines lit. literally lt. litre/s L. Linnaeus Lat. Latin m. metre/s masc. masculine mi. mile/s ml. millilitre/s mod. modern MS(S) manuscript(s) Mt. Mount n., nn. note, notes n.d. no date neut. neuter no. number ns new series NT New Testament OE Old English Ol. Olympiad ON Old Norse OP Old Persian orig. original (e.g. Ger./Fr. orig. [edn.]) OT Old Testament oz. ounce/s p.a. per annum PIE Proto-Indo-European pl. plate plur. plural pref. preface Proc. Proceedings prol. prologue ps.- pseudo- Pt. part ref. reference repr. -

And Myrrh, Cassia, and Frankincense Rode on the Wind a Detailed Look at the Aromatic and Spice Trade of the Classical Mediterranean

University of Mississippi eGrove Honors College (Sally McDonnell Barksdale Honors Theses Honors College) 2013 And Myrrh, Cassia, and Frankincense rode on the Wind A Detailed Look at the Aromatic and Spice Trade of the Classical Mediterranean Forrest Colby Roberts Follow this and additional works at: https://egrove.olemiss.edu/hon_thesis Recommended Citation Roberts, Forrest Colby, "And Myrrh, Cassia, and Frankincense rode on the Wind A Detailed Look at the Aromatic and Spice Trade of the Classical Mediterranean" (2013). Honors Theses. 2102. https://egrove.olemiss.edu/hon_thesis/2102 This Undergraduate Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Honors College (Sally McDonnell Barksdale Honors College) at eGrove. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of eGrove. For more information, please contact [email protected]. And Myrrh, Cassia, and Frankincense Rode on the Wind." A Detailed Look at the Aromatic and Spice Trade of the Classical Mediterranean By: Forrest Colby Roberts A thesis submitted to the faculty of the University of Mississippi in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the Sally McDonnell Barksdale Honors College. Oxford May 2013 Approved by L Advisor: Dr. Aileen Ajootian Reader: Dr. Brada Cook Reader: Di. 'ouglass Sulliyan-Gonzalez ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This thesis is the culmination of four years of hard work as an undergraduate. I would like to thank my parents, Bruce and Hope Roberts, for teaching me the importance of learning and asking questions and for allowing me to pursue a field of study which has challenged me academically. I would like to also thank the Honors College and Classics Department, respectively for giving me every opportunity to advance my knowledge in the field of Classics and my readers. -

The Homicide Courts of Ancient Athens

THE HOMICIDE COURTS OF ANCIENT ATHENS. Early Athens, like other primitive communities, was ruled not by laws, but by customs. The custom in any matter was what everyone did under similar circumstances. As Plato says! "'They [primitive men] could hardly have wanted lawyers as yet; nothing of that sort was likely to have existed in those days, for they had no letters at this early stage; they lived according to custom and the laws of their fathers, as they are termed." I In other words, in the absence of formal laws, justice was synonymous with precedent. At first, crimes, which later were looked upon as offenses against the state, were merely private affairs. Thus murder was only a private offense against the victim and his surviving kinsmen. To have slain a man was a misfortune, for it entailed serious consequences. In the Home- ric civilization the kinsmen might or might not accept wergeld as compensation for the loss and the idea of accepting it was' regarded as a perfectly justifiable alternative to exacting blood, vengeance. By giving presents to the relatives of the murdered man, the offender not only could repair the loss inflicted upon' them by the death of their kinsman, but he could also appease their anger, as the pleasure of revenge would tend to alleviate their indignation' and loss and the humiliation of their enemy would help to heal their resentment. Furthermore, the accept-" ance of compensation was a matter of expediency; for it saved the injured party from the risks involved in carrying out the blood-feud, i. -

The Failure of Athenian Democracy and the Reign of the Thirty Tyrants Lucas D

Eastern Washington University EWU Digital Commons EWU Masters Thesis Collection Student Research and Creative Works 2013 Tyranny and terror: the failure of Athenian democracy and the reign of the Thirty Tyrants Lucas D. LeCaire Eastern Washington University Follow this and additional works at: http://dc.ewu.edu/theses Part of the Anthropology Commons Recommended Citation LeCaire, Lucas D., "Tyranny and terror: the failure of Athenian democracy and the reign of the Thirty Tyrants" (2013). EWU Masters Thesis Collection. 179. http://dc.ewu.edu/theses/179 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Research and Creative Works at EWU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in EWU Masters Thesis Collection by an authorized administrator of EWU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. TYRANNY AND TERROR: THE FAILURE OF ATHENIAN DEMOCRACY AND THE REIGN OF THE THIRTY TYRANTS A Thesis Presented to Eastern Washington University Cheney, WA In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts By Lucas D. LeCaire Spring 2013 THESIS OF LUCAS D. LECAIRE APPROVED BY _________________________________________________ Date_____ Carol Thomas, GRADUATE STUDY COMMITTEE __________________________________________________ Date_____ Julia Smith, GRADUATE STUDY COMMITTEE MASTER’S THESIS In presenting this thesis in partial fulfillment of the requirements for a master’s degree at Eastern Washington University, I agree that the JFK Library shall make copies freely available for inspection. I further agree that copying of this project in whole or in part is allowable only for scholarly purposes. It is understood, however, that any copying or publication of this thesis for commercial purposes, or for financial gain, shall not be allowed without my written permission. -

Some Problems in the Athenian Strategia of the Fifth Century B.C

SOME PROBLEMS IN IHE ATHENIAN STRATEGIA OF THE FIFTH CENTURY B.C. by IETER IAN HENNING, B.A. s) Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts UNIVERSITY OF TASMANIA HOBART December 1974. To the best of my knowledge and belief this thesis contains no material which has been accepted for the award of any other degree or diploma in any university, and contains no copy or paraphrase of material previously published or written by another person except when due reference is made in the text of the thesis. CONTENTS Page •• Abbreviations • • •• iv. Abstract • • •• 1 PART I CHAPTER 1. Ath Pa 22.2 and the Reform of 501/0. 3 CHAPTER 2. Hegemonia and the Command at Marathon 23 CHAPTER 3. Election Procedure 47 PART II CHAPTER 4. The Persian Invasion 480/78 •• 89 CHAPTER 5. Double Representation and the Strategos ex hapanton 113 CHAPTER 6. The Size of the Board .. •• 139 CHAPTER 7. Terminologies in the Sources 180 PART III APPENDIX. 1. List of Generals 211 2. The Strategia - Its Nature and Powers .. .. .. 238 3. Term of Office .. .., 258 4. Possible Double Representations 268 Notes to the Text •• •• 274 Bibliography • • • • •• 339 Abbreviations. I include abbreviations of periodicals and standard reference works in addition to my own special abbreviations of works which have been frequently adverted to in the text and notes. Ant. Class. L'Antiquite classique. AJP American Journal of'Philology. Ath Pal Aristotle, Athenaion Politeia. ATL Meritt, B.D., - Wade - Gery, H.T., - McGregor, , The Athenian Tribute Lists, Cambridge (Mass.), Vol.1, Princeton, vols. -

How Philosophy Became Socratic: a Study of Plato's "Protagoras

How Philosophy Became Socratic C5246.indb i 4/8/10 10:44:19 AM C5246.indb ii 4/8/10 10:44:19 AM GH How Philosophy Became Socratic EF A Study of Plato’s Protagoras, Charmides, and Republic laurence lampert The University of Chicago Press Chicago & London C5246.indb iii 4/8/10 10:44:19 AM Laurence Lampert is professor emeritus of philosophy at Indiana University–Purdue University Indianapolis and the author of Leo Strauss and Nietzsche, also published by the University of Chicago Press. The University of Chicago Press, Chicago 60637 The University of Chicago Press, Ltd., London © 2010 by The University of Chicago All rights reserved. Published 2010 Printed in the United States of America 18 17 16 15 14 13 12 11 10 1 2 3 4 5 isbn-13: 978-0-226-47096-2 (cloth) isbn-10: 0-226-47096-2 (cloth) Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Lampert, Laurence, 1941– How philosophy became socratic : a study of Plato’s Protagoras, Charmides, and Republic / Laurence Lampert. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. isbn-13: 978-0-226-47096-2 (cloth : alk. paper) isbn-10: 0-226-47096-2 (cloth : alk. paper) 1. Socrates. 2. Socrates— Political and social views. 3. Plato. Protagoras. 4. Plato. Republic. 5. Plato. Charmides. 6. Philosophy, Ancient—History. 7. Philosophy, Ancient—Political aspects. 8. Political science—Philosophy. I. Title. b317.l335 2010 184—dc22 2009052793 The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information Sciences—Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ansi z39.48-1992. -

Aspects of Leadership in Xenophon

ASPECTS OF LEADERSHIP IN XENOPHON HISTOS The Online Journal of Ancient Historiography Edited by Christopher Krebs and †John Moles Histos Supplements Supervisory Editor: John Marincola '. Antony Erich Raubitschek, Autobiography of Antony Erich Raubitschek . Edited with Introduction and Notes by Donald Lateiner (-.'/). -. A. J. Woodman, Lost Histories: Selected Fragments of Roman Historical Writers (-.'3). 4. Felix Jacoby, On the Development of Greek Historiography and the Plan for a New Collection of the Fragments of the Greek Historians . Translated by Mortimer Chambers and Stefan Schorn (-.'3). /. Anthony Ellis, ed., God in History: Reading and Re- writing Herodotean Theology from Plutarch to the Renaissance (-.'3). 3. Richard Fernando Buxton, ed., Aspects of Leadership in Xenophon (-.'8) ASPECTS OF LEADERSHIP IN XENOPHON EDITED BY RICHARD FERNANDO BUXTON HISTOS SUPPLEMENT 3 NEWCASTLE UPON TYNE - . ' 8 Published by H I S T O S School of History, Classics and Archaeology, Newcastle University, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE' <RU, United Kingdom ISSN (Online): -./8-3>84 (Print): -./8-3>33 © -.'8 THE INDIVIDUAL CONTRIBUTORS TABLE OF CONTENTS Preface ............................................................................... i About the Contributors ................................................... iii '. Athenian Leaders in Xenophon’s Memorabilia Melina Tamiolaki ............................................................ ' -. Tyrants as Impious Leaders in Xenophon’s Hellenica Frances Pownall ............................................................ -

Areopagus.Pdf

is is a version of an electronic document, part of the series, Dēmos: Clas- sical Athenian Democracy, a publicationpublication ofof e Stoa: a consortium for electronic publication in the humanities [www.stoa.org]. e electronic version of this article off ers contextual information intended to make the study of Athenian democracy more accessible to a wide audience. Please visit the site at http:// www.stoa.org/projects/demos/home. e Council of the Areopagus S e Areopagus, or “Hill of Ares” (Ἀρεῖος πάγος), in Ath- ens was the site of council that served as an important legal institution under the Athenian democracy. is body, called the “Council of the Areopagus,” or simply the “Areopagus,” existed long before the democracy, and its powers and composition changed many times over the centuries. Originally, it was the central governing body of Athens, but under the democracy, it was a primarily the court with jurisdiction over cases of homicide and certain other serious crimes. A er an Athenian had served as one of the nine archons, his conduct in offi ce was investigated, and if he passed that investigation he became a member of the Areopagus. Tenure was for life. I e Areopagus (Ἀρεῖος πάγος) was a hill in Athens, south of the Agora, to the north-west of the Acropolis (Hdt. Christopher W. Blackwell, “ e Areopagus,” in C. Blackwell, ed., Dēmos: Classical Athenian Democracy (A.(A. MahoneyMahoney andand R.R. Scaife, edd., e Stoa: a consortium for electronic publication in the humanities [www.stoa.org], . © , C.W. Blackwell. .). e term “Areopagus,” however, o en refers to the “Council of the Areopagus” (ἡ βουλὴ ἡ ἐξ Ἀρείου πάγου), a governmental institution that met on that hill (Aeschin.