Neglecting the Urban Poor in Bangladesh: Research, Policy and Action in the Context of Climate Change

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NO PLACE for CRITICISM Bangladesh Crackdown on Social Media Commentary WATCH

HUMAN RIGHTS NO PLACE FOR CRITICISM Bangladesh Crackdown on Social Media Commentary WATCH No Place for Criticism Bangladesh Crackdown on Social Media Commentary Copyright © 2018 Human Rights Watch All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America ISBN: 978-1-6231-36017 Cover design by Rafael Jimenez Human Rights Watch defends the rights of people worldwide. We scrupulously investigate abuses, expose the facts widely, and pressure those with power to respect rights and secure justice. Human Rights Watch is an independent, international organization that works as part of a vibrant movement to uphold human dignity and advance the cause of human rights for all. Human Rights Watch is an international organization with staff in more than 40 countries, and offices in Amsterdam, Beirut, Berlin, Brussels, Chicago, Geneva, Goma, Johannesburg, London, Los Angeles, Moscow, Nairobi, New York, Paris, San Francisco, Sydney, Tokyo, Toronto, Tunis, Washington DC, and Zurich. For more information, please visit our website: http://www.hrw.org MAY 2018 ISBN: 978-1-6231-36017 No Place for Criticism Bangladesh Crackdown on Social Media Commentary Summary ........................................................................................................................... 1 Information and Communication Act ......................................................................................... 3 Punishing Government Critics ...................................................................................................4 Protecting Religious -

Housing the Urban Poor: Planning, Business and Politics a Case Study of Duaripara Slum, Dhaka City, Bangladesh

Housing the Urban Poor: Planning, Business and Politics A Case Study of Duaripara Slum, Dhaka city, Bangladesh Kh. Md. Nahiduzzaman Thesis submitted to the Department of Geography, Faculty of Social Sciences and Technology Management, Norwegian University of Science and Technology (NTNU), in partial fulfillment of the requirements for Master of Philosophy in Development Studies, specializing in Geography. Norway, May 2006 NTNU Declaration Except where duly acknowledged, I certify that this thesis is my own work under the supervision of Professor Axel Baudouin of the Department of Geography, Norwegian University of Science and Technology, Trondheim, Norway Kh. Md. Nahiduzzaman Abstract This study is conducted on Duripara slum of Dhaka city which is one of the fastest growing megalopolis and primate cities not only among the developing but also among the developed countries. The high rate of urbanization has posed a challenging dimension to the central, local govt. and concerned development authority. In Dhaka about 50% of the total urban population is poor and in the urbanization process the poor are the major contributors which can be characterized as urbanization of poverty. In response to the emerging urban problems, the development authority makes plan to solve those problems as well as to manage the urban growth. By focusing on the housing issue for the urban poor in Dhaka Metropolitan Development Plan (DMDP), this study is aimed to find out the distortion between plan and reality through making a connection between such planning practice, political connections and business dealings. Knowledge gained from the reviewed literature, structuration theory, actors oriented approach, controversies of urban growth and theoretical framework were used as interpretative guide for the study. -

Various Types of Hand Embroidery As Income Generating Activities in Mohammadpur Urdu Speaking Community: Prospect of Developing Women Entrepreneurs

Various Types of Hand Embroidery as Income Generating Activities in Mohammadpur Urdu Speaking Community: Prospect of Developing Women Entrepreneurs (The study is conducted by the 5th batch students of Gender and Governance Training Program of Democracywatch) Research Instructor: Prof A.S.M Atiqur Rahman Institute of Social Welfare and Research Dhaka University January 2007 Democracywatch 7 Circuit House Road, Dhaka-1000 Acknowledgement The research titled “Various Types of Hand Embroidery as Income Generating Activities in Mohammadpur Urdu Speaking Community: Prospect of Developing Women Entrepreneurs” is a part of the training program organized by Gender and Governance Unit of Democracywatch. Every research requires direct and indirect contribution of various people. We are glad to convey our gratefulness especially to Ms. Taleya Rehman for her kind initiative to conduct this research. We give special thanks to Prof. A.S.M Atiqur Rahman for his continuous supervision. Without his contribution and advice it was impossible to proceed this work. We pay upgrading thanks to Ms. Taherunnesa Abdullah advisor of G.G.U. We are thankful to respondents of “ Jeneva Camp”, “Market Camp” and “Staff Quarter Camp”of Mohammadpur who generously gave their time and shared valuable information. Last but not least we wish to acknowledge the inputs of Khaled .Nasir, Imtiaz ,Shumi and of course, we could not deny the sincere cooperation of Ms.Mansura Akter co-ordinator and Mohammed Mahbub-Un-Nabi Program Assistant of G.G.U. Gender and Governance Training Program -

A Study on the Relationship of Spatial Planning Aspects in Occurrence Of

A Study on the Relationship of Spatial Planning Aspects in Occurrence of Street Crimes in Dhaka City Nakhara: Journal of Environmental Design and Planning Volume 15, December 2018 A Study on the Relationship of Spatial Planning Aspects in Occurrence of Street Crimes in Dhaka City Urmee Chowdhury* / Ishrat Islam** * Faculty of Architectureand Planning, Ahsanullah University of Science and Technology, Bangladesh Corresponding author: [email protected] ** Faculty of Architecture and Planning, Bangladesh University of Engineering and Technology, Bangladesh [email protected] ABSTRACT treet crime, like mugging and vehicle theft, are the significant crime problems in every developing S city of the world. The study area for this research is Dhaka city, which is experiencing an situation of increasing street crime. This research focuses on the relationship between spatial planning and street crimes and tries to recommend different strategies for prevention of crime and violence in the streets of Dhaka city by proposing urban design and infrastructure planning. The study tries to assess the relationship from macro to micro level through different spatial and physical planning components. For the detail level study, four Thana (police station) areas have been selected from Dhaka City Corporation area (DCC) according to their physical layout and other characteristics. In this level, the relationship is studied through the association between spatial layout and different physical planning factors like land use along with some elements of streetscape. Space Syntax methodology was applied to assess the impact of spatial configuration in occurrence of street crime with the selected four study area. In the micro level the study reveals that different types of land use with different design elements lead to change in public activity spaces which have impact on occurrence of street crimes. -

Urban Poverty and Adaptations of the Poor to Urban Life in Dhaka City, Bangladesh

Urban poverty and adaptations of the poor to urban life in Dhaka City, Bangladesh Md. Shahadat Hossain BSS (Hons.), MSS A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the School of Sociology and Anthropology at the University of New South Wales, Sydney, Australia 2006 DEDICATION To the poor people living in Dhaka slums who have honoured this study through their participation ABSTRACT This thesis explores urban poverty and the adaptations of the urban poor in the slums of the megacity of Dhaka, Bangladesh. It seeks to make a contribution to understanding and analysis of the phenomenon of rapid mass urbanisation in the Third World and its social consequences, the formation of huge urban slums and new forms of urban poverty. Its focus is the analysis of poverty which has been overwhelmingly dominated by economic approaches to the neglect of the social questions arising from poverty. This thesis approaches these social questions through an ‘urban livelihood framework’, arguing that this provides a more comprehensive framework to conceptualise poverty through its inclusion of both material and non-material dimensions. The study is based on primary data collected from slums in Dhaka City. Five hundred poor households were surveyed using a structured questionnaire to investigate the economic activities, expenditure and consumption, access to housing and land, family and social networking and cultural and political integration. The survey data was supplemented by qualitative data collected through fifteen in-depth interviews with poor households. The thesis found that poverty in the slums of Dhaka City was most strongly influenced by recent migration from rural areas, household organisation, participation in the ‘informal’ sector of the economy and access to housing and land. -

CURRICULUM VITAE Curriculum Vitae

12/11/2018 Prof. Dr. Gias U. Ahsan CURRICULUM VITAE Curriculum Vitae Prof. Dr. Gias U. Ahsan Ph.D., MPHM, DTM&H (MU), MBBS (CU) SUM M A R Y O F CURRENT POSITION EXPERIENCE & ACHIEVEMENTS Pro Vice Chancellor (Designate) Over 28 years of & Dean, (SHLS), NSU professional and Executive Director, Global Health and Climate Research Institute experience as a senior North South University administrator, teacher and researcher at North A C A D E M I C South University and QUALIFIATION other recognized institutions. 2003 Ph.D in Epidemiology, Faculty of Tropical Medicine, Mahidol University. (Top ranked University of Thailand). Awarded with WHO 15 years of and TDR merit scholarship. administrative & research experiences in Thesis Title: Gender Difference in Tuberculosis Case Detection, different position as Treatment Seeking Behavior and Treatment Compliance of TB Pro vice chancellor (In Patients of Rural Communities of Bangladesh (Conducted With charge), Dean, WHO/TDR scholarship) and Published In High Impact International Department Chairman Journal. & Executive Director at North South University only. 1993 MPHM (Master of Primary Health Care Management), ASEAN Institute for Health Development (AIHD), Mahidol University, Over 100 journal and Thailand. Awarded with scholarship conference papers published. 1992 DTM&H (Diploma in Tropical Medicine and Hygiene), Faculty of Tropical Medicine, Mahidol University, Thailand Over 60 key note papers presented at 1989 MBBS, Sylhet Osmani Medical College, Chittagong University, International and scholarship from Government of Bangladesh National Conferences st 1982 H.S.C (Science) 1 Division with Star Marks & Board Scholar, Outstanding research Comilla Victoria College. and academic performance award 1980 S.S.C (Science) 1st Division with Star Marks & Board Scholar, Daudkandi Govt. -

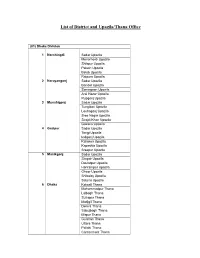

Appendix F: Name of Region, District and Upazila/Thana

List of District and Upazila/Thana Office (01) Dhaka Division 1 Norshingdi Sadar Upozila Monorhordi Upozila Shibpur Upozila Palash Upozila Belab Upozila Raipura Upozila 2 Narayangonj Sadar Upozila Bandor Upozila Sonargaon Upozila Arai Hazar Upozila Rupgonj Upozila 3 Munshigonj Sadar Upozila Tungibari Upozila Louhagonj Upozila Sree Nagar Upozila Sirajdi Khan Upozila Gazaria Upozila 4 Gazipur Sadar Upozila Tongi Upozila kaligonj Upozila Kaliakoir Upozila Kapashia Upozila Sreepur Upozila 5 Manikgonj Sadar Upozila Singair Upozila Daulatpur Upozila Horirampur Upozila Gheor Upozila Shibaloy Upozila Saturia Upozila 6 Dhaka Kotwali Thana Mohammadpur Thana Lalbagh Thana Sutrapur Thana Motijgil Thana Demra Thana Sabujbagh Thana Mirpur Thana Gulshan Thana Uttara Thana Pallabi Thana Cantonment Thana Dhanmondi Thana Tejgaon Thana Ramna Thana Keranigonj Upozila Dohar Upozila Nawabgonj Upozila Savar Upozila Dhamrai Upozila (2) Faridpur Region 1 Faridpur Sadar Upozila Boalmari Upozila Sadarpur Upozila Char Bhadrashon Upozila Bhanga Upozila Nagarkanda Upozila Madhukhali Upozila Alphadanga Upozila SalThanaa Upozila 2 Rajbari Sadar Upozila Pangsha Upozila Goalondo Upozila Kalukhali Upozila Baliakandi Upozila 3 Gopalgonj Sadar Upozila kashiani Upozila Tongipara Upozila Muksudpur Upozila Kotalipara Upozila 4 Madaripur Sadar Upozila Kalkini Upozila Rajoir Upozila Shibchar Upozila 5 Sariyatpur Sadar Upozila Damudda Upozila Noria Upozila Jagira Upozila Vedorgonj Upozila Goshair Hat Upozila (3) Barishal Regeon Sadar Upozila Amtoli Upozila Betagi Upozila 1 Borguna -

Child Labour and Education a Survey of Slum Settlements in Dhaka Maria Quattri and Kevin Watkins

Report Child labour and education A survey of slum settlements in Dhaka Maria Quattri and Kevin Watkins December 2016 Overseas Development Institute 203 Blackfriars Road London SE1 8NJ Tel. +44 (0) 20 7922 0300 Fax. +44 (0) 20 7922 0399 E-mail: [email protected] www.odi.org www.odi.org/facebook www.odi.org/twitter Readers are encouraged to reproduce material from ODI Reports for their own publications, as long as they are not being sold commercially. As copyright holder, ODI requests due acknowledgement and a copy of the publication. For online use, we ask readers to link to the original resource on the ODI website. The views presented in this paper are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily represent the views of ODI. © Overseas Development Institute 2016. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial Licence (CC BY-NC 4.0). Cover photo: Abir Abdullah/ADB: Sohel works in an aluminium factory at Kamrangirchar in Dhaka. Acknowledgements This report was funded through a generous grant from the Bangladesh office of the United Kingdom’s Department for International Development (DFID). Several DFID staff provided helpful comments on a draft proposal and methodology note, including Golam Kibria, Mosharraf Hossain, Tayo Nwaubani and Afroza Chowdhury (Mimi). Colleagues from BRAC Institute of Educational Development, BRAC University (BIED, BRACU) informed the design of the survey and led implementation. The BIED, BRACU team comprised the following members: Md. Altaf Hossain, Md. Abul Kalam and Sheikh Shahana Shimu. We are grateful for the insights, professionalism and dedication of BIED, BRACU’s staff – and it was a privilege to work with them. -

47254-003: Dhaka Water Supply Network Improvement

Initial Environmental Examination Document Stage: Updated Project Number: 47254-003 September 2019 BAN: Dhaka Water Supply Network Improvement Project – ICB Package 2.11 (2nd Batch: DMA: 301, 306, 312, 313 & 1005) Prepared by the Dhaka Water Supply and Sewerage Authority, Government of Bangladesh for the Asian Development Bank. This initial environmental examination is a document of the borrower. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of ADB's Board of Directors, management, or staff, and may be preliminary in nature. Your attention is directed to the “terms of use” section of this website. In preparing any country program or strategy, financing any project, or by making any designation of or reference to a particular territory or geographic area in this document, the Asian Development Bank does not intend to make any judgments as to the legal or other status of any territory or area. CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS (as of 10 February 2019) Currency unit – Taka (Tk) Tk.1.00 = $0.0127 $1.00 = Tk. 84.5 ABBREVIATIONS ADB – Asian Development Bank ARIPA - Acquisition and Requisition of Immovable Properties Act AC - Asbestos Cement AP - Affected person BRTA - Bangladesh Road Transport Authority BC - Bituminous Carpeting BFS - Brick Flat Soling CC - Cement Concrete DWASA -Dhaka Water Supply and Sewerage Authority DWSNIP -Dhaka Water Supply Network Improvement Project DMA - District Metering Area DMSC - Design Management and Supervision Consultants DNCC - Dhaka North City Corporation DSCC - Dhaka South City Corporation DoE - Department -

47254-003: Dhaka Water Supply Network Improvement Project

Initial Environmental Examination Project No. 47254-003 January 2021 BAN: Dhaka Water Supply Network Improvement Project (DWSNIP) ICB Package 2.11 (Fourth Batch: DMA: 406, 411, 412 & 413) This Initial Environmental Examination is a document of the borrower. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of ADB's Board of Directors, Management, or staff, and may be preliminary in nature. In preparing any country program or strategy, financing any project, or by making any designation of or reference to a particular territory or geographic area in this document, the Asian Development Bank does not intend to make any judgments as to the legal or other status of any territory or area. Initial Environmental Examination Project Number: 47254-003 January 2021 BAN: Dhaka Water Supply Network Improvement Project (DWSNIP) ICB Package 2.11 (Fourth Batch: DMA: 406, 411, 412 & 413) Prepared by the Dhaka Water Supply and Sewerage Authority (DWASA), Government of Bangladesh for the Asian Development Bank. This Initial Environmental Examination is a document of the borrower. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of ADB's Board of Directors, Management, or staff, and may be preliminary in nature. In preparing any country program or strategy, financing any project, or by making any designation of or reference to a particular territory or geographic area in this document, the Asian Development Bank does not intend to make any judgments as to the legal or other status of any territory or area. CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS (as of 6 January 2021) Currency unit – Taka (Tk) Tk.1.00 = $0.0118 $1.00 = Tk. -

47254-003: Dhaka Water Supply Network Improvement

Initial Environmental Examination Document Stage: Updated Project Number: 47254-003 February 2020 BAN: Dhaka Water Supply Network Improvement Project – ICB Package 2.11 (3rd Batch: DMA 303, 305,1010 and 1011) - First Group (DMA 303 and 305) Prepared by the Dhaka Water Supply and Sewerage Authority, Government of Bangladesh for the Asian Development Bank. This initial environmental examination is a document of the borrower. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of ADB's Board of Directors, Management, or staff, and may be preliminary in nature. Your attention is directed to the “terms of use” section on ADB’s website. In preparing any country program or strategy, financing any project, or by making any designation of or reference to a particular territory or geographic area in this document, the Asian Development Bank does not intend to make any judgments as to the legal or other status of any territory or area. CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS (as of 5 January 2020) Currency unit – Taka (Tk) Tk.1.00 = $0.0113 $1.00 = Tk. 84.78 ABBREVIATIONS ADB – Asian Development Bank ARIPA - Acquisition and Requisition of Immovable Properties Act AC - Asbestos Cement AP - Affected person AIDS - Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome. BRTA - Bangladesh Road Transport Authority BC - Bituminous Carpeting BFS - Brick Flat Soling CC - Cement Concrete CASE - Clean Air and Sustainable environment CAMS Continuous Air Monitoring Stations DWASA -Dhaka Water Supply and Sewerage Authority DWSNIP -Dhaka Water Supply Network Improvement Project DMA - District -

Main Volume Part I : Current Condition

MAIN VOLUME PART I : CURRENT CONDITION JICA STUDY TEAM Dhaka Urban Transport Network Development Study CHAPTER 1: INTRODUCTION 1.1 Background of the Study Dhaka city is the capital of People’s Republic of Bangladesh. Dhaka is located geographically in the center of the eastern sub-region of South Asia, including India (West Bengal, Meghalaya, Assam and Tripura provinces), Nepal, Bhutan and Myanmar. Among these countries and provinces, Nepal, Bhutan, and Meghalaya, Assam and Tripura provinces in India are located in inland and there is no direct accessibility to the ocean. Thus, seaports in Bangladesh, such as Chittagong and Mongla as well as proposed deep sea port of Cox’s Bazaar have a great potential to be international gateway in the sub-region. The Dhaka Metropolitan Area (DMA) has a population of 10.7 million (7.5% of the total population of the country in 2006). Currently the urban transportation in DMA mostly relies on road transport, where car, bus, auto-rickshaw, rickshaw, etc. are coexistent. This creates serious traffic congestion in addition to health hazard caused by the traffic pollution including air pollution. With the national economic growth the urban population will also increase, and at the same time the number of privately owned automobiles will also increase significantly. So, the improvement of urban public transportation system for DMA has become a pressing issue to improve its traffic situation and urban environment. Considering this situation the government of Bangladesh formulated a ‘Strategic Transportation Plan’ (STP) in cooperation with the World Bank in 2005. The implementing agency was Dhaka Transport Corporation Board (DTCB) under the Ministry of Communication.