At the Trail's End

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Portland City Council Agenda

CITY OF OFFICIAL PORTLAND, OREGON MINUTES A REGULAR MEETING OF THE COUNCIL OF THE CITY OF PORTLAND, OREGON WAS HELD THIS 30TH DAY OF APRIL, 2008 AT 9:30 A.M. THOSE PRESENT WERE: Mayor Potter, Presiding; Commissioners Adams, Leonard and Saltzman, 4. Commissioner Leonard left at 1:05 p.m. OFFICERS IN ATTENDANCE: Susan Parsons, Acting Clerk of the Council; Ben Walters, Senior Deputy City Attorney; and Ron Willis, Sergeant at Arms. On a Y-4 roll call, the Consent Agenda was adopted. Disposition: COMMUNICATIONS 513 Request of Steve Pixley to address Council regarding Portland Parks & Recreation volunteer corps and National Volunteer Week proclamation (Communication) PLACED ON FILE 514 Request of Sara Fritsch from the Leadership Portland Class of 2008 to address Council regarding cigarette litter (Communication) PLACED ON FILE 515 Request of Pavel Goberman to address Council regarding the media (Communication) PLACED ON FILE 516 Request of Glen Owen to address Council regarding an impeachment resolution and ad (Communication) PLACED ON FILE TIME CERTAINS 517 TIME CERTAIN: 9:30 AM – Assess benefited properties for street and stormwater improvements in the SW Texas Green Street Local PASSED TO Improvement District (Hearing; Ordinance introduced by Commissioner SECOND READING Adams; C-10014) MAY 07, 2008 AT 9:30 AM 518 TIME CERTAIN: 10:00 AM – Mill Park Elementary School and Adopt A Class (Presentation introduced by Mayor Potter) PLACED ON FILE 1 of 57 April 30, 2008 519 TIME CERTAIN: 10:30 AM – South Park Block Five Fundraising Report (Report introduced by Commissioner Saltzman) Motion to accept the Report: Moved by Commissioner Leonard and ACCEPTED seconded by Commissioner Adams. -

Sweets for Sweets

Sweets for SWEETHEARTS Winter wonderland | Radiating heat | Discovering your craft February 2015 foxcitiesmagazine.com Celebrating the Place We Call Home. foxcitiesmagazine.com Publishers Marvin Murphy Ruth Ann Heeter Managing Editor Ruth Ann Heeter [email protected] Associate Editor Amy Hanson [email protected] Editorial Interns Jessica Morgan Mia Sato Reid Trier Haley Walters Art Director Jill Ziesemer Graphic Designer Julia Schnese Account Executives Courtney Martin [email protected] Maria Stevens [email protected] Administrative Assistant/Distribution Nancy D’Agostino [email protected] Printed at Spectra Print Corporation Stevens Point, WI FOX CITIES Magazine is published 11 times annually and is available for the subscription rate of $18 for one year. Subscriptions include our annual Worth the Drive publication, delivered in July. For more information or to learn about advertising opportunities, call (920) 733-7788. © 2015 FOX CITIES Magazine. Unauthorized duplication of any or all content of this publication is prohibited and may not be reproduced in any form without permission of the publisher. FOX CITIES Magazine P.O. Box 2496 Appleton, WI 54912 Facebook.com/foxcitiesmagazine Please pass along or recycle this magazine. February 2015 CONTENTS Features COVER STORY ARTS & CULTURE 14 Winter wonderland Recreation clubs make the most of the cold By Amy Hanson AT HOME 18 Radiating heat Flooring options fend off winter’s freeze 22 By Amy Hanson WEDDINGS: Sweets for sweethearts FOOD & DINING Candy bars bring confections to wedding receptions By Amy Hanson 26 Discovering your craft Local breweries offer handcrafted, flavorful options foxcitiesmagazine.com By Reid Trier Take a look at our new look Are you a fan of FOX CITIES Magazine? Well, now you can get even more of the arts, Departments culture and dining content that you look forward to each month on our brand-new website. -

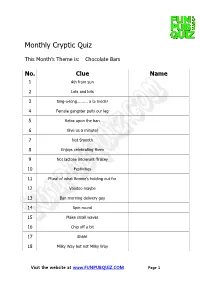

Monthly Cryptic Quiz

Monthly Cryptic Quiz This Month’s Theme is: Chocolate Bars No. Clue Name 1 4th from sun 2 Lots and lots 3 Sing-a-long......... a la mode! 4 Female gangster pulls our leg 5 Relax upon the ban 6 Give us a minute! 7 Not Smooth 8 Enjoys celebrating them 9 Not lactose intolerant Tracey 10 Festivities 11 Plural of what Bonnie's holding out for 12 Voodoo maybe 13 Ban morning delivery guy 14 Spin round 15 Make small waves 16 Chip off a bit 17 Shhh! 18 Milky Way but not Milky Way Visit the website at www.FUNPUBQUIZ.COM Page 1 19 Knock her down twice 20 Assemble the puss 21 Celebrity place to drink 22 Not from Lancashire 23 A BMW a coat 24 Make it more confusing 25 Masticate 26 What Melanie drives 27 Mediterranean Glee 28 Posh guys price plus a Quentin 29 Sky + vowel 30 Hobo 31 Merge 32 Enhancement 33 Marks brother spun around 34 All aboard for it! 35 Outdoor meal 36 King of daytime animation 37 Pants start with a constanant 38 Twisted noel 39 Subject 40 Out on his own cowboy Visit the website at www.FUNPUBQUIZ.COM Page 2 Answers: Rock Bands No. Clue Band Name 1 4th from sun Mars 2 Lots and lots Bounty 3 Sing-a-long......... a la mode! Minstrels 4 Female gangster pulls our leg Maltesers 5 Relax upon the ban Lion Bar 6 Give us a minute! Time out 7 Not Smooth Crunchie 8 Enjoys celebrating them Revels 9 Not lactose intolerant Tracey Milk Tray 10 Festivities Celebrations 11 Plural of what Bonnie's holding out for Heros 12 Voodoo maybe Black Magic 13 Ban morning delivery guy Milky Bar 14 Spin round Twirl 15 Make small waves Ripple 16 Chip off a bit -

JAPANESE TRAVEL PORTLAND / Mini Guide 2016-2017 TRAVEL PORTLAND / Mini Guide 2016-2017

Travel Portland ©2016 Travel Portland / Media Surf Communications Inc. www.travelportland.jp ポ ートラ ン ド ・ ミ ニ ガ イ ド Edit : Travel Portland + Media Surf Communications Inc. Art Direction and Design : Shinpei Onishi Design : Aya Kanamori JAPANESE TRAVEL PORTLAND / Mini Guide 2016-2017 TRAVEL PORTLAND / Mini Guide 2016-2017 Why Portland? Profile_ ケリー・ロイ Kelley Roy ADX と Portland Made Collective の創業者兼オーナー。米 国でのものづくり事業支援から、世界中から寄せられるメイカー Owner / founder スペースのつくり方のコンサルティングまで手がける、アメリカ ADX & Portland Made Collective でのメイカームーヴメントの第一人者。地質学の学位と都市計 画学の修士号を持ち、2010 年にはフードカートについての著書 「Cartopia: Portland ’s Food Cart Revolution 」を出版。ク メイカームーブメントの 震 源 地 リエイティブな人々の技術向上を支え、起業を応援し、「自分の WHY 好きなことをして生きる」人々を助けることに情熱を燃やす。 “ WHY PORTLAND? ” 米国北西部「パシフィック・ノースウ エスト」に属するオレゴン州ポートラ ンド。緑にあふれ、独自のカルチャー を育み、「全米No.1住みたい町」に度々 登場する人口60万人の都市。その魅 力はある人にとっては、緑豊かな環境 比較的小さくコンパクトな大きさの街で、そこに ADXは20 11年に始動しました。様々な背景を持っ ときれいな空気、雄大な山と川であり、 住む人は正義感が強く、ちょっと変わったものや実 た人々を一つ屋根の下に集め、場所とツールと知識を Maker community またある人にとっては、インディペン 験的なものが好き。こんな要因がポートランドを「メ 分かち合い、一緒に働くことによって、この街にあふ デント・ミュージックやアートシーン イカームーブメント」の震源地としています。職人 れるクリエイティブなエネルギーをひとつのところに に象徴される「クール」な面であった 的な技術を生かしてものづくりにあたり、起業家精 集めるというアイデアからはじまったのです。エネル りする。ここで出会う豊かな食文化 神にあふれ、より良いものをつくり出そうという信 ギーに形をあたえることによって、新しいビジネスや とクラフトビールやサードウェーブ・ 念に基づき、リスクを厭わない人々を支援する気質 プロダクトが生み出され、アート、デザイン、製造過 Columns Feature PORTコーヒーをはじめとする新しいドリン が、この街にはあるのです。 程を新しい視点から捉えることができるようになり ク文化も人々を惹きつけてやまない。 ポートランドに移住してくる人の多くが、何か新 ました。ADXは、人と地球と経済に利益をもたらし、 比較的小さなこの都市がなぜ、こんな しいことをはじめたいという夢を持っています。そ 高品質かつ手づくりの製品に価値を置く「アーティサ に注目されているのか。まずは現地に して、まわりにインスパイアされて、同好の士とと ナル・エコノミー(職人経済)」のハブ兼サポートシス -

October 2015

October 13, 2015 - Producer Reinvention In The New Music Economy NEWSLETTER A n E n t e r t a i n m e n t I n d u s t r y O r g a n i z a t i on Big Jim Wright Does It Good: An Interview With Big Jim Wright By Soul Jones Around the mid-nineties, at the Flyte Tyme building in Minneapolis, The President’s Corner whenever owner Jimmy Jam - one half of mega-platinum production duo Jam & Lewis – would take a new superstar client on a tour of the “Happy Birthday.” We know the song, we’ve all sung it but who studio he would make the following introduction. “And in here we owns the rights? Most members of the public didn’t realize Warner/ have Big Jim Wright, he’s one of our writer/producers here at Flyte Chappell was claiming the copyright on this iconic song, although Tyme and he just happens to sing.” Jam would then nod his we in the music business did. Who would have thought one of the trademark trilby towards the young vocalist. “Say Big Jim … just most recognizable songs in the world would not be PD? There has give ‘em a little something.” It would be at that point that he’d mosey been much confusion as to ownership and rights since the recent over to the nearest keyboard. Just so happens that Big Jim Wright, ruling, but what does it all really mean? CCC past President Steve speaking from a phone at his home in Los Angeles California, is sat Winogradsky is here to discuss this important copyright update. -

R41¢4 T! ~ Tt:.1 ~ 1 ********************************************************************* PLEASE AUDITION EACH DISC IMMEDIATELY

r41¢4 t! ~ tt:.1 ~ 1 ********************************************************************* PLEASE AUDITION EACH DISC IMMEDIATELY. IF *TOP40* YOU HAVE ANY QUESTIONS, PLEASE CONTACT US WITH SHADOE STEVENS AT (213) 882-8330. ********************************************************************* TOPICAL PROMOS TOPICAL PROMOS FOR SHOW #31 ARE LOCATED ON DISC 4, TRACKS 6. 7 & 8. DO NOT USE AFTER SHOW #31. AT40 ACTUALITIES ARE LOCATED ON DISC 4. TRACKS 9. 10. 11 & 12. IMMEDIATELY FOLLOWING TOPICAL PROMOS ***AT40 SNEEK PEEK LOCATED ON DISC 4. TRACK 13*** 1' MADONNA RETURNS. BARRY ON TAYLOR AND BRIAN'S SONG :32 Hi, I'm Shadoe Stevens. If you missed American Top 40 last week, you missed new songs from Madonna and Tears For Fears. An AT40 Sneek Peek at P.M. Dawn's latest release ... Barry White told us what he thinks of Taylor Dayne's remake of his hit from the 70's ... had Brian McKnight's story of how he went from Computer Science studies to one of the chart's hottest new singers ... took an AT40 Flashback to the year "Rocky" first climbed into the ring! Plus all the latest Music News and much more. Join me this week for Billboard's biggest hits, from 40 to #1, right here, on American Top 40. (LOCAL TAG) 2. KENNY'S HEROES. JON'S ROCKIN' START AND THE TOP 40 BIRDWOMAN :23 Hi, Shadoe Stevens, AT40. Every week, the stars tell us their stories as we countdown radio's biggest hits from the Billboard chart to #1. Last week, Kenny G. talked about playing Sax with his music heros ... Jon Bon Jovi gave us the story of how he got his rock rollin' and why .. -

Why Meat Prices Have Risen Several Graduating Seniors

Download the DAILY AMERICAN NEWS APP on your tablet or smartphone unes Available at the App Store on iT or for Android on Google Play — Award-Winning Investigative Journalism — WWW.OURTOWNJOHNSTOWN.COM SO-3106631 GJSD WEEK OF planning MAY 13 - 19, 2020 alternate grad event FAMILY VALUES KATIE SMOLEN Our Town Correspondent JOHNSTOWN — Greater Johnstown School District will be holding a virtual graduation for its seniors because of the COVID-19 pandemic. Superintendent Amy Arcurio told the district’s DAUGHTER’S board of directors that she had a contract from WJAC- ESSAY LEADS TV for the station to put TO MOM’S together and air a virtual graduation for $1,700. SELECTION Board President Gene Pentz Photo by Katie Smolen signed the contract during FOR YWCA Shoppers browsing the meat department of Randy’s BiLo along Osborne Street in Johnstown on May. the meeting shortly after it AWARD was mentioned by Arcurio. The decision didn’t sit — B1 well with some, including Why meat prices have risen several graduating seniors. Senior Shaye McClafferty, BRUCE SIWY sylvania and beyond have not workforce, you can’t operate.” who organized a walkout as [email protected] SPORTS been able to place their animals He added that the Pennsyl- a middle school student to into the supply chain because vania Farm Bureau has been protest against the school’s Meat industry insiders say there’s a bottleneck. working with the commonwealth bullying policies, created a chickens, pigs and cattle have not “It really is a national concern,” to provide priority COVID-19 petition on change.org in been the proverbial cash cow of he said. -

Interstate 5 Columbia River Crossing

I NTERSTATE 5 C OLUMBIA R IVER C ROSSING Neighborhoods and Population Technical Report May 2008 TO: Readers of the CRC Technical Reports FROM: CRC Project Team SUBJECT: Differences between CRC DEIS and Technical Reports The I-5 Columbia River Crossing (CRC) Draft Environmental Impact Statement (DEIS) presents information summarized from numerous technical documents. Most of these documents are discipline- specific technical reports (e.g., archeology, noise and vibration, navigation, etc.). These reports include a detailed explanation of the data gathering and analytical methods used by each discipline team. The methodologies were reviewed by federal, state and local agencies before analysis began. The technical reports are longer and more detailed than the DEIS and should be referred to for information beyond that which is presented in the DEIS. For example, findings summarized in the DEIS are supported by analysis in the technical reports and their appendices. The DEIS organizes the range of alternatives differently than the technical reports. Although the information contained in the DEIS was derived from the analyses documented in the technical reports, this information is organized differently in the DEIS than in the reports. The following explains these differences. The following details the significant differences between how alternatives are described, terminology, and how impacts are organized in the DEIS and in most technical reports so that readers of the DEIS can understand where to look for information in the technical reports. Some technical reports do not exhibit all these differences from the DEIS. Difference #1: Description of Alternatives The first difference readers of the technical reports are likely to discover is that the full alternatives are packaged differently than in the DEIS. -

The Folk-Lore of Plants by T.F. Thiselton-Dyer 1889

THE FOLK-LORE OF PLANTS BY T.F. THISELTON-DYER 1889 PREFACE. Apart from botanical science, there is perhaps no subject of inquiry connected with plants of wider interest than that suggested by the study of folk-lore. This field of research has been largely worked of late years, and has obtained considerable popularity in this country, and on the Continent. Much has already been written on the folk-lore of plants, a fact which has induced me to give, in the present volume, a brief systematic summary--with a few illustrations in each case--of the many branches into which the subject naturally subdivides itself. It is hoped, therefore, that this little work will serve as a useful handbook for those desirous of gaining some information, in a brief concise form, of the folk-lore which, in one form or another, has clustered round the vegetable kingdom. T.F. THISELTON-DYER. November 19, 1888. CONTENTS. I. PLANT LIFE II. PRIMITIVE AND SAVAGE NOTIONS RESPECTING PLANTS III. PLANT WORSHIP IV. LIGHTNING PLANTS V. PLANTS IN WITCHCRAFT VI. PLANTS IN DEMONOLOGY VII. PLANTS IN FAIRY-LORE VIII. LOVE-CHARMS IX. DREAM-PLANTS X. PLANTS AND THE WEATHER XI. PLANT PROVERBS XII. PLANTS AND THEIR CEREMONIAL USE XIII. PLANT NAMES XIV. PLANT LANGUAGE XV. FABULOUS PLANTS XVI. DOCTRINE OF SIGNATURES XVII. PLANTS AND THE CALENDAR XVIII. CHILDREN'S RHYMES AND GAMES XIX. SACRED PLANTS XX. PLANT SUPERSTITIONS XXI. PLANTS IN FOLK-MEDICINE XXII. PLANTS AND THEIR LEGENDARY HISTORY XXIII. MYSTIC PLANTS CHAPTER I. PLANT LIFE. The fact that plants, in common with man and the lower animals, possess the phenomena of life and death, naturally suggested in primitive times the notion of their having a similar kind of existence. -

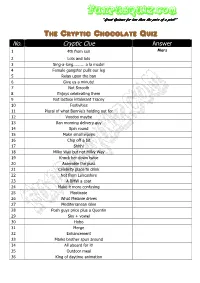

FPQ Jubilee Chocolate Quiz

FUNPUBQUIZ. Com “““GGGreatGreat Quizzes for less than the price of a pint!˝ The Cryptic Chocolate Quiz No. Cryptic Clue Answer 1 4th from sun Mars 2 Lots and lots 3 Sing-a-long......... a la mode! 4 Female gangster pulls our leg 5 Relax upon the ban 6 Give us a minute! 7 Not Smooth 8 Enjoys celebrating them 9 Not lactose intolerant Tracey 10 Festivities 11 Plural of what Bonnie's holding out for 12 Voodoo maybe 13 Ban morning delivery guy 14 Spin round 15 Make small waves 16 Chip off a bit 17 Shhh! 18 Milky Way but not Milky Way 19 Knock her down twice 20 Assemble the puss 21 Celebrity place to drink 22 Not from Lancashire 23 A BMW a coat 24 Make it more confusing 25 Masticate 26 What Melanie drives 27 Mediterranean Glee 28 Posh guys price plus a Quentin 29 Sky + vowel 30 Hobo 31 Merge 32 Enhancement 33 Marks brother spun around 34 All aboard for it! 35 Outdoor meal 36 King of daytime animation FUNPUBQUIZ. Com “““GGGreatGreat Quizzes for less than the price of a pint!˝ 37 Pants start with a constanant 38 Twisted noel 39 Subject 40 Out on his own cowboy 41 Planets not hatched 42 Confectionary network 43 Direction not near 44 Scruff up the hair 45 Use the oar to unlock the door 46 Opposite to merge 47 Flightless bird 48 Caveman's weapon is in superb condition 49 Vixen's timeless 50 Cab! 51 Those and those 52 Small meal 53 Ageing Caribbean isle 54 Only the best live here 55 The same the other way around 56 Clever ones 57 Romantic flowers 58 No credit here just... -

OREGON LIQUOR CONTROL COMMISSION Page 1 of 683 Licensed Businesses As of 8/12/2018 4:10A.M

OREGON LIQUOR CONTROL COMMISSION Page 1 of 683 Licensed Businesses As of 8/12/2018 4:10A.M. License License Secondary Location Tradename Licensee Name Type Mailing Address Premises Address Premises No. License No. Expires County To License # #1 FOOD 4 MART FUN 4 U INC O PO BOX 5026 729 SW 185TH 28426 271408 03/31/2019 WASHINGTON BEAVERTON, OR 97006 ALOHA, OR 97006 Phone: 503-502-9271 00 WINES 00 OREGON LLC WY 937 NW GLISAN ST #1037 801 N SCOTT ST 58406 272542 03/31/2019 YAMHILL PORTLAND, OR 97209 CARLTON, OR 97111 Phone: 503-852-6100 1 800 WINESHOP.COM 1 800 WINESHOP.COM INC DS 525 AIRPARK RD 51973 267742 12/31/2018 OUTSIDE OR NAPA, CA 94558 Phone: 800-946-3746 1 AM MARKET 1 AM MARKET INC O PO BOX 46 320 N MAIN ST 4346 275587 06/30/2019 DOUGLAS RIDDLE, OR 97469 RIDDLE, OR 97469 Phone: 541-874-2722 1 AM MARKET 1 AM MARKET INC O PO BOX 46 1931 NE STEPHENS 4379 275588 06/30/2019 DOUGLAS RIDDLE, OR 97469 ROSEBURG, OR 97470 Phone: 541-673-0554 10 BARREL BREWING COMPANY 10 BARREL BREWING LLC WY ONE BUSCH PLACE / 202-1 1135 NW GALVESTON AVE SUITE A 46579 260298 09/30/2018 DESCHUTES 260297 ST LOUIS, MO 63118 BEND, OR 97703 Phone: 541-678-5228 10 BARREL BREWING COMPANY 10 BARREL BREWING LLC F-COM ONE BUSCH PLACE / 202-1 62950 & 62970 NE 18TH ST 49506 259722 09/30/2018 DESCHUTES ST LOUIS, MO 63118 BEND, OR 97701 Phone: 541-585-1007 10 BARREL BREWING COMPANY 10 BARREL BREWING LLC F-COM ONE BUSCH PLACE / 202-1 1135 NW GALVESTON AVE SUITE A 57088 259724 09/30/2018 DESCHUTES ST LOUIS, MO 63118 BEND, OR 97703 Phone: 541-678-5228 10 BARREL BREWING COMPANY -

KLBD Kosher Certified Retail Products List

KLBD Kosher Certified Retail Products List Section 1 Food Categories and Company Contact Details Section 2 Full Product List As the kosher statuses are subject to change, please request an up-to-date kosher certificate directly from the manufacturer or supplier. Tel: + 44 (0) 20 8343 6255 www.klbdkosher.org Sign up to the KLBD New Products Newsletter @KLBDkosher COMPANY INDEX AND CONTACT INFO Go to Home Go to Products Category Company Website Phone Email Name Country Sold Aluminum Trays Nicholl Food Packaging + 44 (0) 1543 460400 UK Baked Goods Green Isle Foods Ltd www.northernfoods.co m +353 433 340 800 UK Baked Goods The Family Bread www.thefamilybread.co. Limited uk +44 (0) 20 3372 4737 Baking Supplies GB Ingredients Ltd www.lallemand.com +44 (0) 1394 606 400 UK Baking Supplies Knightsbridge PME www.cakedecoration.co. uk +44 (0) 20 3234 0049 UK Cereals Dorset Cereals Limited www.dorsetcereals.co.u k +44 (0) 1305 751000 UK Cereals Scrumshus Granola Limited www.scrumshus.co.uk +44 (0) 20 8455 8557 UK Cereals SuperLife Ltd www.superlife.ie +353 86 256 7993 [email protected] UK Cereals Weetabix Ltd www.weetabix.co.uk +44 (0) 1536 722 181 UK and Israel Cheese Charedi Dairies +44 (0) 20 8800 5766 UK Cheese Schwartz S Ltd Chips McCain Foods (GB) Limited www.mccain.com +44 (0) 1723 584141 UK Organic Seed & Bean www.seedandbean.co.u Chocolates Company Limited k +44 (0) 20 8343 5420 UK Cider & Perry H. Weston & Sons www.westons- Limited cider.co.uk +44 (0) 1531 660 233 UK Cleaning Materials The London Oil Refining www.astonishcleaners.c