Into the Net Neal Ascherson

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bob Doyle 12Th February 1916

Bob Doyle: 12th February 1916 - 22nd January 2009: 'An Unus... http://www.indymedia.ie/article/90779 features events publish about us contact us traditional newswire Advanced Search enter search text here Bob Doyle: 12th February 1916 - 22nd January Publishing Guide 2009: 'An Unusual Communist' Recent articles by anarchaeologist Featured Stories international | miscellaneous | feature Friday January 23, 2009 23:37 Up to 600 take to the streets of Open Newswire by anarchaeologist Dublin to say farewell to Bob Doyle 11 comments Latest News The death has Opinion and Analysis Cheap winter goodies, mulled wine Press Releases occurred in London and seasonal scoff... 0 comments Event Calendar of Bob Doyle, the Other Press last surviving Irish Images of Spanish Civil War Latest Comments soldier of the XV volunteers now on line 4 comments International Photo Gallery Recent Articles about International Brigade of the Miscellaneous News Archives Spanish Hidden Articles Republican Army. The revolution delayed: 10 years of Hugo List Bob, whose health Chávezʼs rule Feb 21 09 by El Libertario, had been failing for Venezuela Videos some time had Autonomous Republic Declared in Dublin survived a recent Feb 20 09 by Citizen of the Autonomous double heart Republic of Creative Practitio attack, before Why BC performed best behind closed passing peacefully doors Feb 10 09 by Paul O' Sullivan about us | help us last night surrounded by his Upcoming Events family. He was a few weeks short of International | Miscellaneous his 93rd birthday. Apr 09 Bring back Bob's career as an APSO...for one night political activist has only! been recorded in his book Jun 14 The Brigadista, which Palestinian Summer recounted his early Celebration 2009 life in Dublin as a Republican volunteer and later New Events as a member of the Bob Doyle International Republican Congress, prior to his abortive first attempt to fight against Franco in July 1937, which saw him stow away on a 06 Mar International ship to Valencia. -

The Real 007 Used Fake News to Get the U.S. Into World War II About:Reader?Url=

The Real 007 Used Fake News to Get the U.S. into World War II about:reader?url=http://www.thedailybeast.com/articles/2017/01/29/the-r... thedailybeast.com Marc Wortman01.28.17 10:00 PM ET Photo Illustration by Elizabeth Brockway/The Daily Beast CLOAK & DAGGER The British ran a massive and illegal propaganda operation on American soil during World War II—and the White House helped. In the spring of 1940, British Prime Minister Winston S. Churchill was certain of one thing for his nation caught up in a fight to the death with Nazi Germany: Without American support his 1 of 11 3/20/2017 4:45 PM The Real 007 Used Fake News to Get the U.S. into World War II about:reader?url=http://www.thedailybeast.com/articles/2017/01/29/the-r... nation might not survive. But the vast majority of Americans—better than 80 percent by some polls—opposed joining the fight to stop Hitler. Many were even against sending any munitions, ships or weapons to the United Kingdom at all. To save his country, Churchill had not only to battle the Nazis in Europe, he had to win the war for public opinion among Americans. He knew just the man for the job. In May 1940, as defeated British forces were being pushed off the European continent at Dunkirk, Churchill dispatched a soft-spoken, forty-three-year-old Canadian multimillionaire entrepreneur to the United States. William Stephenson traveled under false diplomatic passport. MI6—the British secret intelligence service—directed Stephenson to establish himself as a liaison to American intelligence. -

Spain in Our Hearts: Americans in the Spanish Civil War, 1936Ndash;1939 Online

A9XVt [Free download] Spain in Our Hearts: Americans in the Spanish Civil War, 1936ndash;1939 Online [A9XVt.ebook] Spain in Our Hearts: Americans in the Spanish Civil War, 1936ndash;1939 Pdf Free Adam Hochschild ebooks | Download PDF | *ePub | DOC | audiobook #86213 in Books 2016-03-29 2016-03-29Original language:EnglishPDF # 1 9.00 x 1.48 x 6.00l, #File Name: 0547973187464 pages | File size: 72.Mb Adam Hochschild : Spain in Our Hearts: Americans in the Spanish Civil War, 1936ndash;1939 before purchasing it in order to gage whether or not it would be worth my time, and all praised Spain in Our Hearts: Americans in the Spanish Civil War, 1936ndash;1939: 2 of 2 people found the following review helpful. RivetingBy Alan C. JasperA story that needed to be told this well, written with a clarity of both language and intent. The narrative follows a timeline and pays respect to, without blindly fawning over the idealism of the Lincoln Brigade. At the same time, it frankly acknowledges the snakes in the garden of Stalin's international communism, though the author does not delve into its political theory or elucidate its "road to serfdom." The perfidy of Franco, of the Nationalist fascists and of their civilian, ecclesiastic and foreign supporters is on the other hand well described.0 of 0 people found the following review helpful. A compelling work of literatureBy Jack WendelkenI knew very little about the Spanish Civil war. Although I had read many books about World War One and Two,I'll admit to being somewhat clueless about this war. -

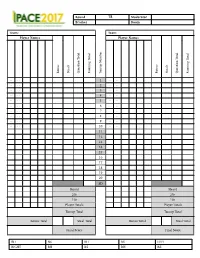

Round Moderator Bracket Room Team

Round 18 Moderator Bracket Room Team: Team: Player Names Player Names Steals Bonus Steals Question Total Running Total Bonus Running Total Tossup Number Question Total .. .. 1 .. .. .. .. 2 .. .. .. .. 3 .. .. .. .. 4 .. .. .. .. 5 .. .. .. .. 6 .. .. .. .. 7 .. .. .. .. 8 .. .. .. .. 9 .. .. .. .. 10 .. .. 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 SD Heard Heard 20s 20s 10s 10s Player Totals Player Totals Tossup Total Tossup Total Bonus Total Steal Total Bonus Total Steal Total Final Score Final Score RH RS BH BS LEFT RIGHT BH BS RH RS PACE NSC 2017 - Round 18 - Tossups 1. A small sculpture by this man depicts a winged putto with a faun's tail wearing what look like chaps, exposing his rear end and genitals. Padua's Piazza del Santo is home to a sculpture by this man in which one figure rests a hoof on a small sphere representing the world. His Atys is currently held in the Bargello along with his depiction of St. George, which like his St. Mark was originally sculpted for a niche of the (*) Orsanmichele. The equestrian statue of Marcus Aurelius inspired this man's depiction of Erasmo da Narni. The central figure holds a large sword and rests his foot on a helmeted head in a sculpture by this artist that was the first freestanding male nude produced since antiquity. For 10 points, name this Florentine sculptor of Gattamelata and that bronze David. ANSWER: Donatello [or Donatello Niccolò di Betto Bardi] <Carson> 2. Minnesota Congressman John T. Bernard cast the only dissenting vote against a law banning US intervention in this conflict. Torkild Rieber of Texaco supplied massive quantities of oil to the winning side in this war. -

Hispanic-Americans and the Spanish Civil War (1936-1939)

Southern Methodist University SMU Scholar History Theses and Dissertations History Spring 2020 INTERNATIONALISM IN THE BARRIOS: HISPANIC-AMERICANS AND THE SPANISH CIVIL WAR (1936-1939) Carlos Nava [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.smu.edu/hum_sci_history_etds Recommended Citation Nava, Carlos, "INTERNATIONALISM IN THE BARRIOS: HISPANIC-AMERICANS AND THE SPANISH CIVIL WAR (1936-1939)" (2020). History Theses and Dissertations. 11. https://scholar.smu.edu/hum_sci_history_etds/11 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the History at SMU Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in History Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of SMU Scholar. For more information, please visit http://digitalrepository.smu.edu. INTERNATIONALISM IN THE BARRIOS: HISPANIC-AMERICANS AND THE SPANISH CIVIL WAR (1936-1939) Approved by: ______________________________________ Prof. Neil Foley Professor of History ___________________________________ Prof. John R. Chávez Professor of History ___________________________________ Prof. Crista J. DeLuzio Associate Professor of History INTERNATIONALISM IN THE BARRIOS: HISPANIC-AMERICANS AND THE SPANISH CIVIL WAR (1936-1939) A Thesis Presented to the Graduate Faculty of Dedman College Southern Methodist University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Master of Arts with a Major in History by Carlos Nava B.A. Southern Methodist University May 16, 2020 Nava, Carlos B.A., Southern Methodist University Internationalism in the Barrios: Hispanic-Americans in the Spanish Civil War (1936-1939) Advisor: Professor Neil Foley Master of Art Conferred May 16, 2020 Thesis Completed February 20, 2020 The ripples of the Spanish Civil War (1936-1939) had a far-reaching effect that touched Spanish speaking people outside of Spain. -

John Lehmann and the Acclimatisation of Modernism in Britain

JOHN LEHMANN AND THE ACCLIMATISATION OF MODERNISM A.T. Tolley It is easy to see the cultural history of modernism in terms of key volumes, such as Auden’s Poems of 1930, and to see their reception in the light of significant reviews by writers who themselves have come to have a regarded place in the history of twentieth-century literature. Yet this is deceptive and does not give an accurate impression of the reaction of most readers. W.B. Yeats, in a broadcast on “Modern Poetry” in 1936 could say of T.S. Eliot: “Tristam and Iseult were not a more suitable theme than Paddington Railway Station.”1 Yeats was then an old man; but most of Yeats’s listeners would have shared the hostility. Yet, in the coming years, acclimatisation had taken place. Eliot’s Little Gidding, published separately as a pamphlet in December 1942, sold 16,775 copies – a remarkable number for poetry, even in those wartime years when poetry had such impact. John Lehmann had a good deal to do with the acclimatisation of modernist idiom, most notably through his editing of New Writing, New Writing & Daylight and The Penguin New Writing, the last of which had had at its most popular a readership of about 100,000. The cultural impact of modernism came slowly in Britain, most notably through the work of Eliot and Virginia Woolf. The triumph of modernism came with its second generation, through the work of Auden, MacNeice and Dylan Thomas in poetry, and less markedly through the work of Isherwood and Henry Green in prose. -

The Treason of Rockefeller Standard Oil (Exxon) During World War II

The Treason Of Rockefeller Standard Oil (Exxon) During World War II By The American Chronicle February 4, 2012 We have reported on Wall Street’s financing of Hitler and Nazi programs prior to World War 2 but we have not given as much attention to its treasonous acts during the war. The depths to which these men of fabled wealth sent Americans to their deaths is one of the great untold stories of the war. John Rockefeller, Jr. appointed William Farish chairman of Standard Oil of New Jersey which was later rechristened Exxon. Farish lead a close partnership with his company and I. G. Farben, the German pharmaceutical giant whose primary raison d'etre was to occlude ownership of assets and financial transactions between the two companies, especially in the event of war between the companies' respective nations. This combine opened the Auschwitz prison camp on June 14, 1940 to produce artificial rubber and gasoline from coal using proprietary patents rights granted by Standard. Standard Oil and I. G. Farben provided the capital and technology while Hitler supplied the labor consisting of political enemies and Jews. Standard withheld these patents from US military and industry but supplied them freely to the Nazis. Farish plead “no contest” to criminal conspiracy with the Nazis. A term of the plea stipulated that Standard would provide the US government the patent rights to produce artificial rubber from Standard technology while Farish paid a nominal 5,000 USD fine Frank Howard, a vice president at Standard Oil NJ, wrote Farish shortly after war broke out in Europe that he had renewed the business relationship described above with Farben using Royal Dutch Shell mediation top provide an additional layer of opacity. -

Anti-Fascism, Anti-Communism, and Memorial Cultures: a Global

ANTI-FASCISM, ANTI-COMMUNISM, AND MEMORIAL CULTURES: A GLOBAL STUDY OF INTERNATIONAL BRIGADE VETERANS by Jacob Todd Bernhardt A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in History Boise State University May 2021 © 2021 Jacob Todd Bernhardt ALL RIGHTS RESERVED BOISE STATE UNIVERSITY GRADUATE COLLEGE DEFENSE COMMITTEE AND FINAL READING APPROVALS of the thesis submitted by Jacob Todd Bernhardt Thesis Title: Anti-Fascism, Anti-Communism, and Memorial Cultures: A Global Study of International Brigade Veterans Date of Final Oral Examination: 08 March 2021 The following individuals read and discussed the thesis submitted by student Jacob Todd Bernhardt, and they evaluated the student’s presentation and response to questions during the final oral examination. They found that the student passed the final oral examination. John P. Bieter, Ph.D. Chair, Supervisory Committee Shaun S. Nichols, Ph.D. Member, Supervisory Committee Peter N. Carroll, Ph.D. Member, Supervisory Committee The final reading approval of the thesis was granted by John P. Bieter, Ph.D., Chair of the Supervisory Committee. The thesis was approved by the Graduate College. DEDICATION For my dear Libby, who believed in me every step of the way. iv ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Throughout the writing of this thesis, I have received a great deal of support and assistance. I would first like to thank my Committee Chair, Professor John Bieter, whose advice was invaluable in broadening the scope of my research. Your insightful feedback pushed me to sharpen my thinking and brought my work to a higher level. I would like to thank Professor Shaun Nichols, whose suggestions helped me improve the organization of my thesis and the power of my argument. -

El English Captain De Thomas Wintringham (1939)

EL ENGLISH CAPTAIN DE THOMAS WINTRINGHAM (1939). MEMORIA Y OLVIDO DE UN BRIGADISTA BRITÁNICO English Captain by Thomas Wintringham (1939). Memory and oblivion of a British volunteer Luis ARIAS GONZÁLEZ Fecha de aceptación definitiva: 15-09-2009 RESUMEN: Thomas Wintringham llegó a ser jefe del Batallón Británico de las Brigadas Internacionales en la batalla del Jarama; sobre su experiencia en la Guerra Civil española, escribió un libro que es mucho más que unas memorias al uso al ofrecer aspectos originales de análisis e interpretación de la misma y un reflejo de su compleja personalidad. Tanto su agitada vida como su trayectoria política de izquier- das —que fue desde el comunismo más estricto al laborismo— quedarían marca- das para siempre por su intervención en España y este hecho y esta obra le convertirían en uno de los mayores expertos teóricos militares ingleses de todos los tiempos. Palabras clave: Thomas Wintringham, Brigadas Internacionales, Guerra Civil, memorias, expertos teóricos militares. ABSTRACT: Thomas Wintringham became the commanding officer of the Bri- tish Battalion in the International Brigades during the Battle of Jarama; he wrote a book about his experiences in the Spanish Civil War which is more than memories are usual because it offers original points of view about it and a real image of his complex personality. His very hectic life was affected by this experience such as his © Ediciones Universidad de Salamanca Stud. hist., H.ª cont., 26, 2008, pp. 273-303 LUIS ARIAS GONZÁLEZ 274 EL ENGLISH CAPTAIN DE THOMAS WINTRINGHAM (1939). MEMORIA Y OLVIDO DE UN BRIGADISTA BRITÁNICO left-wing political belief —from dogmatic communism to Labour Party—. -

Cómo Citar El Artículo Número Completo Más Información Del

Revista de Economía Institucional ISSN: 0124-5996 Universidad Externado de Colombia Braden, Spruille EL EMBAJADOR SPRUILLE BRADEN EN COLOMBIA, 1939-1941 Revista de Economía Institucional, vol. 19, núm. 37, 2017, Julio-Diciembre, pp. 265-313 Universidad Externado de Colombia DOI: https://doi.org/10.18601/01245996.v19n37.13 Disponible en: https://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=41956426013 Cómo citar el artículo Número completo Sistema de Información Científica Redalyc Más información del artículo Red de Revistas Científicas de América Latina y el Caribe, España y Portugal Página de la revista en redalyc.org Proyecto académico sin fines de lucro, desarrollado bajo la iniciativa de acceso abierto EL EMBAJADOR SPRUILLE BRADEN EN COLOMBIA, 1939-1941 Spruille Braden* * * * pruille Braden (1894-1978) fue embajador en Colombia entre 1939 y 1942, durante la presidencia de Eduardo Santos. Aprendió el español desdeS niño y conocía bien la cultura latinoamericana. Nació en Elkhor, Montana, pero pasó su infancia en una mina de cobre chilena, de pro- piedad de su padre, ingeniero de grandes dotes empresariales. Regresó a Estados Unidos para cursar su enseñanza secundaria. Estudió en la Universidad de Yale donde, siguiendo el ejemplo paterno, se graduó como ingeniero de minas. Regresó a Chile, trabajó con su padre en proyectos mineros y se casó con una chilena de clase alta. Durante su estadía sura- mericana no descuidó los vínculos políticos con Washington. Participó en la Conferencia de Paz del Chaco, realizada en Buenos Aires (1935-1936), y pasó al mundo de la diplomacia estadounidense, con embajadas en Colombia y en Cuba (1942-1945), donde estrechó lazos con el dictador Fulgencio Batista. -

Wall Street and the Rise of Hitler

TABLE OF CONTENTS Preface Introduction Unexplored Facets of Naziism PART ONE: Wall Street Builds Nazi Industry Chapter One Wall Street Paves the Way for Hitler 1924: The Dawes Plan 1928: The Young Plan B.I.S. — The Apex of Control Building the German Cartels Chapter Two The Empire of I.G. Farben The Economic Power of I.G. Farben Polishing I.G. Farben's Image The American I.G. Farben Chapter Three General Electric Funds Hitler General Electric in Weimar, Germany General Electric & the Financing of Hitler Technical Cooperation with Krupp A.E.G. Avoids the Bombs in World War II Chapter Four Standard Oil Duels World War II Ethyl Lead for the Wehrmacht Standard Oil and Synthetic Rubber The Deutsche-Amerikanische Petroleum A.G. Chapter Five I.T.T. Works Both Sides of the War Baron Kurt von Schröder and I.T.T. Westrick, Texaco, and I.T.T. I.T.T. in Wartime Germany PART TWO: Wall Street and Funds for Hitler Chapter Six Henry Ford and the Nazis Henry Ford: Hitler's First Foreign Banker Henry Ford Receives a Nazi Medal Ford Assists the German War Effort Chapter Seven Who Financed Adolf Hitler? Some Early Hitler Backers Fritz Thyssen and W.A. Harriman Company Financing Hitler in the March 1933 Elections The 1933 Political Contributions Chapter Eight Putzi: Friend of Hitler and Roosevelt Putzi's Role in the Reichstag Fire Roosevelt's New Deal and Hitler's New Order Chapter Nine Wall Street and the Nazi Inner Circle The S.S. Circle of Friends I.G. Farben and the Keppler Circle Wall Street and the S.S. -

There's a Valley in Spain Called Jarama

There's a valley in Spain called Jarama The development of the commemoration of the British volunteers of the International Brigades and its influences D.G. Tuik Studentno. 1165704 Oudendijk 7 2641 MK Pijnacker Tel.: 015-3698897 / 06-53888115 Email: [email protected] MA Thesis Specialization: Political Culture and National Identities Leiden University ECTS: 30 Supervisor: Dhr Dr. B.S. v.d. Steen 27-06-2016 Image frontpage: photograph taken by South African photographer Vera Elkan, showing four British volunteers of the International Brigades in front of their 'camp', possibly near Albacete. Imperial War Museums, London, Collection Spanish Civil War 1936-1939. 1 Contents Introduction : 3 Chapter One – The Spanish Civil War : 11 1.1. Historical background – The International Brigades : 12 1.2. Historical background – The British volunteers : 14 1.3. Remembering during the Spanish Civil War : 20 1.3.1. Personal accounts : 20 1.3.2. Monuments and memorial services : 25 1.4. Conclusion : 26 Chapter Two – The Second World War, Cold War and Détente : 28 2.1. Historical background – The Second World War : 29 2.2. Historical background – From Cold War to détente : 32 2.3. Remembering between 1939 and 1975 : 36 2.3.1. Personal accounts : 36 2.3.2. Monuments and memorial services : 40 2.4. Conclusion : 41 Chapter Three – Commemoration after Franco : 43 3.1. Historical background – Spain and its path to democracy : 45 3.1.1. The position of the International Brigades in Spain : 46 3.2. Historical background – Developments in Britain : 48 3.2.1. Decline of the Communist Party of Great Britain : 49 3.2.2.