Macroprudential Policy, Countercyclical Bank Capital Buffers

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Growth of Central Banking: the Societe Generale Des Pays-Bas And

Growth of Central Banking: The Soci•t• Ge•e•rale des Pays-Bas and the Impact of the Function of General State Cashier on Belgium's Monetary System (1822-1830) Julienne M. Laureyssens University of Manitoba I intend to reexamine in this paper the creation and the first ten odd years of operation of Belgium's first corporate bank, the SocaeteG(n•rale des Pays-Bas,with special regard to its function as General State Cashier. The bank was founded in 1822 by King William I of the United Kingdom of the Netherlands. It was the only corporate bank in the southern part of the Netherlands until 1835. During the Dutch period, which lasted until September 1830 and up to the creation of the National Bank of Belgium in 1850, it carried out some of the functions of a central bank. King William I had an extensive knowledge of financial affairs, in fact, they were his private passion. According to Demoulin, he consideredbanks to be "des creatmns para-•'ta- tiques," institutions that are the state's "helpmates" whether they are owned and managed privately or not. The bank's particular function within the spectrum of the state's tasks were to mobilize BUSINESS AND ECONOMIC HISTORY., Second Series, Volume Fourteen, 1985. Copyright (c) 1985 by the Board of Trustees of the University of Illinois. Library of Congress Catalog No. 85-072859. 125 126 capital and to extend the benefits of credit. William I was a firm believer in paper money, in the beneficial use of a wide variety of paper debt instruments, and in low interest rates. -

Monetary Policy and Bank Risk-Taking: Evidence from the Corporate Loan Market

Monetary Policy and Bank Risk-Taking: Evidence from the Corporate Loan Market Teodora Paligorova∗ Bank of Canada E-mail: [email protected] Jo~aoA. C. Santos∗ Federal Reserve Bank of New York and Nova School of Business and Economics E-mail: [email protected] November 22, 2012 Abstract Our investigation of banks' corporate loan pricing policies in the United States over the past two decades finds that monetary policy is an important driver of banks' risk-taking incentives. We show that banks charge riskier borrowers (relative to safer borrowers) lower premiums in periods of easy monetary policy than in periods of tight monetary policy. This interest rate discount is robust to borrower-, loan-, and bank-specific factors, macroe- conomic factors and various types of unobserved heterogeneity at the bank and firm levels. Using individual bank information about lending standards from the Senior Loan Officers Opinion Survey (SLOOS), we unveil evidence that the interest rate discount for riskier borrowers in periods of easy monetary policy is prevalent among banks with greater risk appetite. This finding confirms that the loan pricing discount we observe is indeed driven by the bank risk-taking channel of monetary policy. JEL classification: G21 Key words: Monetary policy, risk-taking channel, loan spreads ∗The authors thank Jose Berrospide, Christa Bouwman, Daniel Carvalho, Scott Hendry, Kim Huynh, David Martinez-Miera and seminar participants at Nova School of Business and Economics, SFU Beedie School of Business, the 2012 FIRS Meeting in Minneapolis, and the 2012 Bank of Spain and Bank of Canada \International Financial Markets" Workshop for useful comments. -

List of Certain Foreign Institutions Classified As Official for Purposes of Reporting on the Treasury International Capital (TIC) Forms

NOT FOR PUBLICATION DEPARTMENT OF THE TREASURY JANUARY 2001 Revised Aug. 2002, May 2004, May 2005, May/July 2006, June 2007 List of Certain Foreign Institutions classified as Official for Purposes of Reporting on the Treasury International Capital (TIC) Forms The attached list of foreign institutions, which conform to the definition of foreign official institutions on the Treasury International Capital (TIC) Forms, supersedes all previous lists. The definition of foreign official institutions is: "FOREIGN OFFICIAL INSTITUTIONS (FOI) include the following: 1. Treasuries, including ministries of finance, or corresponding departments of national governments; central banks, including all departments thereof; stabilization funds, including official exchange control offices or other government exchange authorities; and diplomatic and consular establishments and other departments and agencies of national governments. 2. International and regional organizations. 3. Banks, corporations, or other agencies (including development banks and other institutions that are majority-owned by central governments) that are fiscal agents of national governments and perform activities similar to those of a treasury, central bank, stabilization fund, or exchange control authority." Although the attached list includes the major foreign official institutions which have come to the attention of the Federal Reserve Banks and the Department of the Treasury, it does not purport to be exhaustive. Whenever a question arises whether or not an institution should, in accordance with the instructions on the TIC forms, be classified as official, the Federal Reserve Bank with which you file reports should be consulted. It should be noted that the list does not in every case include all alternative names applying to the same institution. -

Financial Stability Report 2019

2019 Report Financial Stability National Bank of Belgium FINANCIAL STABILITY REPORT 2019 Financial Stability Report 2019 © National Bank of Belgium All rights reserved. Reproduction of all or part of this publication for educational and non‑commercial purposes is permitted provided that the source is acknowledged. Contents Executive summary 7 Macroprudential Report 9 A. Introduction 9 B. Main risks and points for attention and prudential measures adopted 10 Financial Stability Overview 43 Banking sector 43 Insurance sector 68 Additional charts and tables for the banking and insurance sector 80 Thematic articles 89 Transaction-level data sets and monitoring of systemic risk : an illustration with Securities Holding Statistics 91 Climate-related risks and sustainable finance. Results and conclusions from a sector survey 107 A risk dashboard for detecting and monitoring systemic risk in Belgium 129 Statistical Annex 149 5 Executive summary 1. In the current macro-financial context, monitoring financial stability risks continues to be of great importance. In addition to the growing relevance for financial stability of a range of structural trends and risks – such as the intensive digitisation of the financial sector or risks related to climate change – the macro-financial impact of a persistent low interest rate environment is becoming increasingly apparent. Although a highly accommodative monetary policy on the part of the ECB is justified, given the current macroeconomic situation, the acceleration of the credit cycle in many EU countries, including Belgium, is an important warning that such a policy can also have adverse spillover effects and present potential risks to financial stability. The build‑up of vulnerabilities in Belgium in the form of an increasing debt ratio of households and companies or rising exposure of the financial sector to undervalued or under-priced financial risks may, in the long term, affect the resilience and absorption capacity of the Belgian economy in the event of major shocks. -

Tax Relief Country: Italy Security: Intesa Sanpaolo S.P.A

Important Notice The Depository Trust Company B #: 15497-21 Date: August 24, 2021 To: All Participants Category: Tax Relief, Distributions From: International Services Attention: Operations, Reorg & Dividend Managers, Partners & Cashiers Tax Relief Country: Italy Security: Intesa Sanpaolo S.p.A. CUSIPs: 46115HAU1 Subject: Record Date: 9/2/2021 Payable Date: 9/17/2021 CA Web Instruction Deadline: 9/16/2021 8:00 PM (E.T.) Participants can use DTC’s Corporate Actions Web (CA Web) service to certify all or a portion of their position entitled to the applicable withholding tax rate. Participants are urged to consult TaxInfo before certifying their instructions over CA Web. Important: Prior to certifying tax withholding instructions, participants are urged to read, understand and comply with the information in the Legal Conditions category found on TaxInfo over the CA Web. ***Please read this Important Notice fully to ensure that the self-certification document is sent to the agent by the indicated deadline*** Questions regarding this Important Notice may be directed to Acupay at +1 212-422-1222. Important Legal Information: The Depository Trust Company (“DTC”) does not represent or warrant the accuracy, adequacy, timeliness, completeness or fitness for any particular purpose of the information contained in this communication, which is based in part on information obtained from third parties and not independently verified by DTC and which is provided as is. The information contained in this communication is not intended to be a substitute for obtaining tax advice from an appropriate professional advisor. In providing this communication, DTC shall not be liable for (1) any loss resulting directly or indirectly from mistakes, errors, omissions, interruptions, delays or defects in such communication, unless caused directly by gross negligence or willful misconduct on the part of DTC, and (2) any special, consequential, exemplary, incidental or punitive damages. -

Curriculum Vital February 2017 GABRIEL

Curriculum Vital February 2017 GABRIEL JIMÉNEZ ZAMBRANO Bank of Spain Directorate General of Financial Stability and Resolution Financial Stability Department Alcalá, 50 28014 Madrid, Spain Phone: + 34 91 338 57 10 e-mail: [email protected] EDUCATION Abril 2013 ESADE: Executive MBA on Leadership Development, June 2001 CEMFI (Bank of Spain): MSc in Economics and Finance. June 1999 University Complutense of Madrid: Bachelor of Arts Degree in Mathematics (Special Prize) WORK EXPERIENCE Since May 2015 Head of the Regulatory Impact Assessment Unit, Directorate General Financial Stability and Resolution, Financial Stability Department, Banco de España. Dec. 2007-April 2015 Head of the Banking Sector Analysis Unit, Directorate General Regulation, Financial Stability Department, Banco de España. Sept. 01-Nov. 07 Economist, Directorate General Regulation, Financial Stability Department, Banco de España. PRIZES 2015 Jaime Fernández de Araoz on Corporate Finance PUBLICATIONS (in chronological order) When Credit Dries Up: Job Losses in the Great Recession (with S. Bentolila and M. Jansen) Journal of the European Economic Association, forthcoming, 2017. Macroprudential Policy, Countercyclical Bank Capital Buffers and Credit Supply: Evidence from the Spanish Dynamic Provisioning Experiments (with S. Ongena, J. L. Peydró and J. Saurina) Journal of Political Economy, forthcoming, 2017. 1 Hazardous Times for Monetary Policy: What do Twenty-Three Million Bank Loans say About the Effects of Monetary Policy on Credit Risk-Taking? (with S. Ongena, J. L. Peydró and J. Saurina) Econometrica, 82 (2), 463-505, 2014. How Does Competition Impact Bank Risk Taking? (with J. A. López and J. Saurina) Journal of Financial Stability, 9, 185-195, 2013. Credit Supply and Monetary Policy: Identifying the Bank Balance-Sheet Channel with Loan Applications (with S. -

Download (PDF)

Review essay : Central banking through the centuries Working Paper Research by Ivo Maes October 2018 No 345 Editor Jan Smets, Governor of the National Bank of Belgium Statement of purpose: The purpose of these working papers is to promote the circulation of research results (Research Series) and analytical studies (Documents Series) made within the National Bank of Belgium or presented by external economists in seminars, conferences and conventions organised by the Bank. The aim is therefore to provide a platform for discussion. The opinions expressed are strictly those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Bank of Belgium. Orders For orders and information on subscriptions and reductions: National Bank of Belgium, Documentation - Publications service, boulevard de Berlaimont 14, 1000 Brussels Tel +32 2 221 20 33 - Fax +32 2 21 30 42 The Working Papers are available on the website of the Bank: http://www.nbb.be © National Bank of Belgium, Brussels All rights reserved. Reproduction for educational and non-commercial purposes is permitted provided that the source is acknowledged. ISSN: 1375-680X (print) ISSN: 1784-2476 (online) NBB WORKING PAPER No. 345 – OCTOBER 2018 Abstract Anniversaries are occasions for remembrance and reflections on one’s history. Many central banks take the occasion of an anniversary to publish books on their history. In this essay we discuss five recent books on the history of central banking and monetary policy. In these volumes, the Great Financial Crisis and the way which it obliged central banks to reinvent themselves occupies an important place. Although this was certainly not the first time in the history of central banking, the magnitude of the modern episode is remarkable. -

The Conduct of Monetary Policy in the Face of Technological Change: Theory and Postwar U.S

BANCO DE MÉXICO 407 The Conduct of Monetary Policy in the Face of Technological Change: Theory and Postwar U.S. Evidence Jordi Gali* Abstract The present paper analyzes the implications of technological change for the design and conduct of monetary policy, using an optimizing sticky price model as a reference framework. I show how the optimal policy seeks to insulate the price level from the effects of changes in productivity. I provide some evidence that suggests that the Federal Reserve has responded to technological change in a way consistent with that rule in the Volcker-Greenspan era, but not during the pre-Volcker period. The second part of the paper discusses the conceptual difference between the notion of output gap arising in the new sticky price para- digm, and conventional measures of that variable. I also provide some evidence, based on postwar U.S. data, of the quantitative significance of that discrepancy. Finally, I perform a simple exercise to illustrate how a well intentioned monetary policy designed to stabilize inflation and the output gap could lead to unnecessary instability in both vari- ables if a conventional (but incorrect) measure of the output gap was used. ∗Prepared for the conference on Stabilization and Monetary Policy: the International Experience hosted by the Banco de México, November 14-15, 2000. Parts of the paper draw on past and ongoing work in collaboration with Mark Gertler, David Lopez- Salido, and Javier Valles They do not share responsibility for any errors or misinterpretation contained in the present paper. 408 STABILIZATION AND MONETARY POLICY I. Introduction A number of developments taking place in recent years have brought technological change to the forefront of the economic policy debate. -

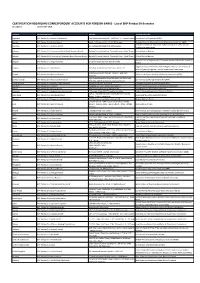

CERTIFICATION REGARDING CORRESPONDENT ACCOUNTS for FOREIGN BANKS - List of BNP Paribas SA Branches Last Update: 11 December 2018

CERTIFICATION REGARDING CORRESPONDENT ACCOUNTS FOR FOREIGN BANKS - List of BNP Paribas SA Branches Last update: 11 December 2018 Country Name of the entity Address Banking authority Argentina BNP Paribas S.A. Buenos Aires Branch Casa Central Bouchard 547, PISOS 26 Y 27 - Capital Federal Central Bank of Argentina (BCRA) Austria BNP Paribas S.A. Austria Branch Vordere Zollamtsstraße 13, A-1030 Vienna Austrian Financial Market Authority (Finanzmarktaufsicht - FMA) Australian Prudential Regulation Authority/Australian Securites and Australia BNP Paribas S.A. Australia Branch 60 Castlereagh Street NSW 2000 Sydney Investments commission Bahrain BNP Paribas S.A. Conventional Retail Bank Manama Branch Barhain Financial Harbour, Financial Center - West Tower Central Bank of Bahrain Bahrain BNP Paribas S.A. Conventional Wholesale Bank Manama Branch Barhain Financial Harbour, Financial Center - West Tower Central Bank of Bahrain National Bank of Belgium (NBB)/Financial Services and Market Authority Belgium BNP Paribas S.A. Belgium Branch 3 rue Montagne du Parc, 1000 Bruxelles (FSMA) Bulgarian National Bank/Financial Intelligence Directorate of National Bulgaria BNP Paribas S.A. Sofia Branch 2 Blv Tzar Osvoboditel, 1000 Sofia - PO Box 11 Security Agency/Bulgarian Financial Supervision Commission 1981 Avenue McGill College - Quebec - H3A 2W8 Canada BNP Paribas S.A. Montreal Branch Office of the Superintendent of Financial Institutions (OFSI) Montréal Elgin Avenue Picadilly Centre 4th floor, PO BOX 10632 Cayman Islands BNP Paribas S.A. Grand Cayman Branch Cayman Islands Monetary Authority (CIMA) APO, KY1-1006 Gran Cayman, Cayman Islands Czech Republic BNP Paribas S.A. pobočka Česká Republika Ovocný trh 8 - 117 19 Praha 1 Czech National Bank (Česká národní banka) Denmark BNP Paribas S.A. -

Monetary Policy Rules in the Pre-Emu Era Is There a Common Rule?1

WORKING PAPER SERIES NO 659 / JULY 2006 MONETARY POLICY RULES IN THE PRE-EMU ERA IS THERE A COMMON RULE? ISSN 1561081-0 by Maria Eleftheriou, Dieter Gerdesmeier 9 771561 081005 and Barbara Roffia WORKING PAPER SERIES NO 659 / JULY 2006 MONETARY POLICY RULES IN THE PRE-EMU ERA IS THERE A COMMON RULE?1 by Maria Eleftheriou 2, Dieter Gerdesmeier and Barbara Roffia 3 In 2006 all ECB publications will feature This paper can be downloaded without charge from a motif taken http://www.ecb.int or from the Social Science Research Network from the €5 banknote. electronic library at http://ssrn.com/abstract_id=913334 1 The paper does not necessarily reflect views of either the European Central Bank or the European University Institute. 2 European University Institute, Economics Department, e-mail: [email protected]. Supervision and support by Professor Helmut Lütkepohl and Professor Michael J. Artis are gratefully acknowledged. 3 European Central Bank, Kaiserstrasse 29, 60311 Frankfurt am Main, Germany; fax: 0049-69-13445757; e-mail: [email protected] and e-mail: [email protected] Very useful comments by F. Smets and an anonymous referee are gratefully acknowledged. © European Central Bank, 2006 Address Kaiserstrasse 29 60311 Frankfurt am Main, Germany Postal address Postfach 16 03 19 60066 Frankfurt am Main, Germany Telephone +49 69 1344 0 Internet http://www.ecb.int Fax +49 69 1344 6000 Telex 411 144 ecb d All rights reserved. Any reproduction, publication and reprint in the form of a different publication, whether printed or produced electronically, in whole or in part, is permitted only with the explicit written authorisation of the ECB or the author(s). -

It's All in the Mix: How Monetary and Fiscal Policies Can Work Or Fail

GENEVA REPORTS ON THE WORLD ECONOMY 23 Elga Bartsch, Agnès Bénassy-Quéré, Giancarlo Corsetti and Xavier Debrun IT’S ALL IN THE MIX HOW MONETARY AND FISCAL POLICIES CAN WORK OR FAIL TOGETHER ICMB INTERNATIONAL CENTER FOR MONETARY AND BANKING STUDIES CIMB CENTRE INTERNATIONAL D’ETUDES MONETAIRES ET BANCAIRES IT’S ALL IN THE MIX HOW MONETARY AND FISCAL POLICIES CAN WORK OR FAIL TOGETHER Geneva Reports on the World Economy 23 INTERNATIONAL CENTER FOR MONETARY AND BANKING STUDIES (ICMB) International Center for Monetary and Banking Studies 2, Chemin Eugène-Rigot 1202 Geneva Switzerland Tel: (41 22) 734 9548 Fax: (41 22) 733 3853 Web: www.icmb.ch © 2020 International Center for Monetary and Banking Studies CENTRE FOR ECONOMIC POLICY RESEARCH Centre for Economic Policy Research 33 Great Sutton Street London EC1V 0DX UK Tel: +44 (20) 7183 8801 Fax: +44 (20) 7183 8820 Email: [email protected] Web: www.cepr.org ISBN: 978-1-912179-39-8 IT’S ALL IN THE MIX HOW MONETARY AND FISCAL POLICIES CAN WORK OR FAIL TOGETHER Geneva Reports on the World Economy 23 Elga Bartsch BlackRock Investment Institute Agnès Bénassy-Quéré University Paris 1 Panthéon-Sorbonne, Paris School of Economics and CEPR Giancarlo Corsetti University of Cambridge and CEPR Xavier Debrun National Bank of Belgium and European Fiscal Board ICMB INTERNATIONAL CENTER FOR MONETARY AND BANKING STUDIES CIMB CENTRE INTERNATIONAL D’ETUDES MONETAIRES ET BANCAIRES THE INTERNATIONAL CENTER FOR MONETARY AND BANKING STUDIES (ICMB) The International Center for Monetary and Banking Studies (ICMB) was created in 1973 as an independent, non-profit foundation. -

Annual Performance Report 2019, June 2020

Annual Performance Report 2019 June 2020 B O A R D O F G O V E R N O R S O F T H E F E D E R A L R E S E R V E S YSTEM Annual Performance Report 2019 June 2020 B O A R D O F G O V E R N O R S O F T H E F E D E R A L R E S E R V E S YSTEM This and other Federal Reserve Board reports and publications are available online at https://www.federalreserve.gov/publications/default.htm. To order copies of Federal Reserve Board publications offered in print, see the Board’s Publication Order Form (https://www.federalreserve.gov/files/orderform.pdf) or contact: Printing and Fulfillment Mail Stop K1-120 Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System Washington, DC 20551 (ph) 202-452-3245 (fax) 202-728-5886 (email) [email protected] iii Preface Congress founded the Federal Reserve System accountable to the general public and the (System) in 1913 as the central bank of the United Congress. States. While established as an independent central • Integrity. The Board adheres to the highest stan- bank, it is subject to oversight by the Congress and dards of integrity in its dealings with the public, must work within the framework of the overall the U.S. government, the financial community, and objectives of economic and financial policy estab- its employees. lished by its enabling statutes. Over time, the Con- gress has expanded the Federal Reserve’s role in the • Excellence.