Librarytrendsv12i1 Opt.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

LIBRARY DESIGN SHOWCASE P

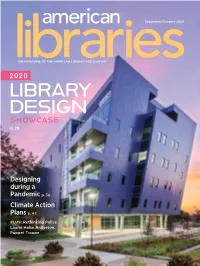

September/October 2020 THE MAGAZINE OF THE AMERICAN LIBRARY ASSOCIATION 2020 LIBRARY DESIGN SHOWCASE p. 28 Designing during a Pandemic p. 36 Climate Action Plans p. 42 PLUS: Rethinking Police, Laurie Halse Anderson, Puppet Troupe PLA 2020 VIRTUAL STREAM NOW ON-DEMAND Educational programs from the PLA 2020 Virtual Conference are now available on-demand*, including: Bringing Technology and Arts Programming to Senior Adults Creating a Diverse, Patron-Driven Collection Decreasing Barriers to Library Use Going Fearlessly Fine-Free Intentional Inclusion: Disrupting Middle Class Bias in Library Programming Leading from the Middle Part Playground, Part Laboratory: Building New Ideas at Your Library Programming for All Abilities Training Staff to Serve Patrons Experiencing Homelessness in the Suburbs We're All Tech Librarians Now Cost: for PLA members for Nonmembers for Groups *Programs are sold separately. www.ala.org/pla/education/onlinelearning/pla2020/ondemand September/October 2020 American Libraries | Volume 51 #9/10 | ISSN 0002-9769 2020 LIBRARY DESIGN SHOWCASE The year’s most impressive new and renovated spaces | p. 28 BY Phil Morehart 22 FEATURES 22 2020 ALA Award Winners Honoring excellence and 42 leadership in the profession 36 Virus-Responsive Design In the age of COVID-19, architects merge future-facing innovations with present-day needs BY Lara Ewen 50 42 Ready for Action As cities undertake climate action plans, libraries emerge as partners BY Mark Lawton 46 Rethinking Police Presence Libraries consider divesting from law enforcement BY Cass Balzer 50 Encoding Space Shaping learning environments that unlock human potential BY Brian Mathews and Leigh Ann Soistmann ON THE COVER: Library Learning Center at Texas Southern University in Houston. -

Downloading—Marquee and the More You Teach Copyright, the More Students Will Punishment Typically Does Not Have a Deterrent Effect

June 2020 THE MAGAZINE OF THE AMERICAN LIBRARY ASSOCIATION COPING in the Time of COVID-19 p. 20 Sanitizing Collections p. 10 Rainbow Round Table at 50 p. 26 PLUS: Stacey Abrams, Future Library Trends, 3D-Printing PPE Thank you for keeping us connected even when we’re apart. Libraries have always been places where communities connect. During the COVID19 pandemic, we’re seeing library workers excel in supporting this mission, even as we stay physically apart to keep the people in our communities healthy and safe. Libraries are 3D-printing masks and face shields. They’re hosting virtual storytimes, cultural events, and exhibitions. They’re doing more virtual reference than ever before and inding new ways to deliver additional e-resources. And through this di icult time, library workers are staying positive while holding the line as vital providers of factual sources for health information and news. OCLC is proud to support libraries in these e orts. Together, we’re inding new ways to serve our communities. For more information and resources about providing remote access to your collections, optimizing OCLC services, and how to connect and collaborate with other libraries during this crisis, visit: oc.lc/covid19-info June 2020 American Libraries | Volume 51 #6 | ISSN 0002-9769 COVER STORY 20 Coping in the Time of COVID-19 Librarians and health professionals discuss experiences and best practices 42 26 The Rainbow’s Arc ALA’s Rainbow Round Table celebrates 50 years of pride BY Anne Ford 32 What the Future Holds Library thinkers on the 38 most -

The Newberry Annual Report 2016 – 17

The Newberry A nnua l Repor t 2016 – 17 Letter from the Chair and the President hat a big and exciting year the Newberry had in 2016-17! As Wan institution, we have been very much on the move, and on behalf of the Board of Trustees and Staff we are delighted to offer you this summary of the destinations we reached last year and our plans for moving forward in 2017-18. Financially, the Newberry enjoyed much success in the past year. Excellent performance by the institution’s investments, up 13.2 percent overall, put us well ahead of the performance of such bellwether endowments as those of Harvard and Yale. Our drawdown on investments for operating expenses was a modest 3.8 percent, well Chair of the Board of Trustees Victoria J. Herget and below the traditional target of 5.0 percent. In fact, of total operating Newberry President David Spadafora expenses only 22.9 percent had to be funded through spending from the endowment—a reduction by more than half of our level of reliance on endowment a decade ago. Partly this change has resulted from improvement in Annual Fund giving: in 2016-17 we achieved the greatest-ever single- year tally of new gifts for unrestricted operating expenses, $1.75 million, some 42 percent higher than just before the economic crisis 10 years ago. Funding for restricted purposes also grew last year, with generous gifts from foundations and individuals for specific programs and projects. Partly, too, our good financial results are owing to continued judicious control of expenses, exemplified by the fact that total staffing levels were 2.7 percent lower in 2016-17 than in 2006-07. -

2019 ALA Impact Report

FIND THE LIBRARY AT YOUR PLACE 2019 IMPACT REPORT THIS REPORT HIGHLIGHTS ALA’S 2019 FISCAL YEAR, which ended August 31, 2019. In order to provide an up-to-date picture of the Association, it also includes information on major initiatives and, where available, updated data through spring 2020. MISSION The mission of the American Library Association is to provide leadership for the development, promotion, and improvement of library and information services and the profession of librarianship in order to enhance learning and ensure access to information for all. MEMBERSHIP ALA has more than 58,000 members, including librarians, library workers, library trustees, and other interested people from every state and many nations. The Association services public, state, school, and academic libraries, as well as special libraries for people working in government, commerce and industry, the arts, and the armed services, or in hospitals, prisons, and other institutions. Dear Colleagues and Friends, 2019 brought the seeds of change to the American Library Association as it looked for new headquarters, searched for an executive director, and deeply examined how it can better serve its members and the public. We are excited to give you a glimpse into this momentous year for ALA as we continue to work at being a leading voice for information access, equity and inclusion, and social justice within the profession and in the broader world. In this Impact Report, you will find highlights from 2019, including updates on activities related to ALA’s Strategic Directions: • Advocacy • Information Policy • Equity, Diversity, and Inclusion • Professional & Leadership Development We are excited to share stories about our national campaigns and conferences, the expansion of our digital footprint, and the success of our work to #FundLibraries. -

The Newberry Annual Report 2019–20

The Newberry A nnua l Repor t 2019–20 30 Fall/Winter 2020 Letter from the Chair and the President Dear Friends and Supporters of the Newberry, The Newberry’s 133rd year began with sweeping changes in library leadership when Daniel Greene was appointed President and Librarian in August 2019. The year concluded in the midst of a global pandemic which mandated the closure of our building. As the Newberry staff adjusted to the abrupt change of working from home in mid-March, we quickly found innovative ways to continue engaging with our many audiences while making Chair of the Board of Trustees President and Librarian plans to safely reopen the building. The Newberry David C. Hilliard Daniel Greene responded both to the pandemic and to the civil unrest in Chicago and nationwide with creativity, energy, and dedication to advancing the library’s mission in a changed world. Our work at the Newberry relies on gathering people together to think deeply about the humanities. Our community—including readers, scholars, students, exhibition visitors, program attendees, volunteers, and donors—brings the library’s collection to life through research and collaboration. After in-person gatherings became impossible, we joined together in new ways, connecting with our community online. Our popular Adult Education Seminars, for example, offered a full array of classes over Zoom this summer, and our public programs also went online. In both cases, attendance skyrocketed, and we were able to significantly expand our geographic reach. With the Reading Rooms closed, library staff responded to more than 450 research questions over email while working from home. -

A Narrative of Augusta Baker's Early Life and Her Work As a Children's Librarian Within the New York Public Library System B

A NARRATIVE OF AUGUSTA BAKER’S EARLY LIFE AND HER WORK AS A CHILDREN’S LIBRARIAN WITHIN THE NEW YORK PUBLIC LIBRARY SYSTEM BY REGINA SIERRA CARTER DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Educational Policy Studies in the Graduate College of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 2016 Urbana, Illinois Doctoral Committee: Professor James Anderson, Chair Professor Anne Dyson Professor Violet Harris Associate Professor Yoon Pak ABSTRACT Augusta Braxston Baker (1911-1998) was a Black American librarian whose tenure within the New York Public Library (NYPL) system lasted for more than thirty years. This study seeks to shed light upon Baker’s educational trajectory, her career as a children’s librarian at NYPL’s 135th Street Branch, her work with Black children’s literature, and her enduring legacy. Baker’s narrative is constructed through the use of primary source materials, secondary source materials, and oral history interviews. The research questions which guide this study include: 1) How did Baker use what Yosso described as “community cultural wealth” throughout her educational trajectory and time within the NYPL system? 2) Why was Baker’s bibliography on Black children’s books significant? and 3) What is her lasting legacy? This study uses historical research to elucidate how Baker successfully navigated within the predominantly White world of librarianship and established criteria for identifying non-stereotypical children’s literature about Blacks and Black experiences. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Philippians 4:13 New Living Translation (NLT) ”For I can do everything through Christ,[a] who gives me strength.” I thank GOD who is my Everything. -

Literature, CO Dime Novels

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 068 991 CS 200 241 AUTHOR Donelson, Ken, Ed. TITLE Adolescent Literature, Adolescent Reading and the English Class. INSTITUTION Arizona English Teachers Association, Tempe. PUB DATE Apr 72 NOTE 147p. AVAILABLE FROMNational Council of Teachers of English, 1111 Kenyon Road, Urbana, Ill. 61801 (Stock No. 33813, $1.75 non-member, $1.65 member) JOURNAL CIT Arizona English Bulletin; v14 n3 Apr 1972 EDRS PRICE MF-$0.65 HC-$6.58 DESCRIPTORS *Adolescents; *English; English Curriculum; English Programs; Fiction; *Literature; *Reading Interests; Reading Material Selection; *Secondary Education; Teaching; Teenagers ABSTRACT This issue of the Arizona English Bulletin contains articles discussing literature that adolescents read and literature that they might be encouragedto read. Thus there are discussions both of literature specifically written for adolescents and the literature adolescents choose to read. The term adolescent is understood to include young people in grades five or six through ten or eleven. The articles are written by high school, college, and university teachers and discuss adolescent literature in general (e.g., Geraldine E. LaRoque's "A Bright and Promising Future for Adolescent Literature"), particular types of this literature (e.g., Nicholas J. Karolides' "Focus on Black Adolescents"), and particular books, (e.g., Beverly Haley's "'The Pigman'- -Use It1"). Also included is an extensive list of current books and articles on adolescent literature, adolescents' reading interests, and how these books relate to the teaching of English..The bibliography is divided into (1) general bibliographies,(2) histories and criticism of adolescent literature, CO dime novels, (4) adolescent literature before 1940, (5) reading interest studies, (6) modern adolescent literature, (7) adolescent books in the schools, and (8) comments about young people's reading. -

A Concise Annotated Bibliography of Library Services to Children and Young Adults: 1930-1939

Abbie Anderson L535: Spring, 2003 1 of 8 A Concise Annotated Bibliography of Library Services to Children and Young Adults: 1930-1939 Alexander, Margaret [later Edwards]. “Introducing Books to Young Readers.” Bulletin of the American Library Association 32.10 (Oct 1938): 685-90, 734. Offers pointers for getting to know individual teen readers and their tastes, encouraging librarians to be flexible in their approach and to respect teen’s frank opinions and intelligence about their own needs. Firm proponent of necessity for wide variety in reading material (both for teens and librarians), with no censorship. Batchelder, Mildred. “The Leadership Network in Children’s Librarianship: A Remembrance.” Stepping Away from Tradition: Children’s Books of the Twenties and Thirties . Ed. Sybille A. Jagusch. Washington, D.C.: Library of Congress, 1988. 70-120. History of children’s librarianship in first half of twentieth century, with detailed recollections of prominent librarians and children’s book editors from 1920’s through 1940’s. Brainard, Jessie F. “The Use of Pictures in the School Library.” Library Journal 55 (Sep 15, 1930): 728-29. Describes experiment at Horace Mann School for Boys in New York. Corridor- length bulletin board in hallway serves as rotating display of art prints, tourism posters (colorful and easy and cheap to get), objects such as pottery and stained glass, and even an exhibition by a local artist. Great success in presenting art and stimulating interest in art, lacking space for a proper art room; also stimulated organization of art library for use in classrooms. Dickson, Paul. “The Thirties—Bread Lines of the Spirit.” The Library in America: A Celebration in Words and Pictures . -

COLLEGE and RESEARCH LIBRARIES News from the Field

ACRL Subject Specialists Section Law and Political Science Subsection Bylaws Adopted at a meeting of the subsection in Montreal, June 20, 1960. ARTICLE I. NAME The name of this organization is the Law and Political Science Subsection of the ACRL Subject Specialists Section. ARTICLE II. OBJECT The Subsection represents in the American Library Association specialists in the field of law and political science and librarians working in this subject area. It acts for the ACRL Subject Specialists Section, in cooperation with other professional groups, in regard to those aspects of library service that require special knowledge of law and political science. ARTICLE III. MEMBERSHIP Any member of the ACRL Subject Specialists Section may elect membership in this Sub section upon payment of his dues to the American Library Association and any such addi tional dues as may be required for such membership. Every member has the right to vote. Any personal member is eligible to hold office. ARTICLE IV. MEETINGS Ten members constitute a quorum for any meeting of the Subsection. ARTICLE V. COMMITTEES The Executive Committee consists of the chairman, the chairman-elect, the immediate past chairman, the secretary, and one member-at-large. The members of the Executive Com mittee shall be selected so as to assure approxmiately equal representation to the areas of law and of political science. The Executive Committee shall serve as the Program Committee. The chairman may ap point two additional members to the Program Committee from the membership at large for one year. ARTICLE VI. GENERAL PROVISIONS Wherever these Bylaws make no specific provisions, the organization of, and procedure in, the Subsection shall correspond to that set forth in the Bylaws of the ACRL Subject Specialists Section. -

Of Nightingales, Newberies, Realism, and the Right Books, 1937-1945

Women of ALA Youth Services and Professional Jurisdiction: Of Nightingales, Newberies, Realism, and the Right Books, 1937-1945 CHRISTINEA. JENKINS ABSTRACT YOUTHSERVICES LIBRARIANSHIP-work with young people in school and pub- lic libraries-has always been a female-intensive specialization. The or- ganization of youth services librarians within the American Library Asso- ciation (ALA) has been a powerful professional force since the turn of the century, with the evaluation and promotion of “the right book for the right child holding a central position in their professional jurisdiction. However, during the late 1930s and early 1940s, this jurisdiction over the selection of the best books for young readers was strongly challenged on the basis of gender. An examination of these confrontations reveals con- sistent patterns in both the attacks and the defenses, as well as gender- based assumptions, that ALA youth services leaders confronted in their ultimately successful effort to defend their jurisdiction over the Newbery Medal (awarded yearly to “the most distinguished contribution to litera- ture for children”), while at the same time broadening the profession’s criteria for “the right book to include realistic fiction that dealt with contemporary social issues. INTRODUCTION Youth services librarianship, like teaching, social work, and public health nursing, was one of the child welfare professions that grew up in the United States during the Progressive Era. In the final decades of the nineteenth century, the rapid growth of industrialization and urbaniza- tion, the influx of enormous numbers of immigrants to the United States, and an economic depression stimulated a host of reform activities and Christine A.Jenkins, Graduate School of Library and Information Science, 501 E. -

Annual Report of the Librarian of Congress. 1966

I L.C. Card 6-6273 I The design on the couer and title page of the paperbound copies of this report and on the flyleaf and title page of the hardbound copies is from a woodblock print of the Library of Congress by Un'ichi Haratsuka, reproduced by permission of the artist. , . UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE WASHINGTON : 1967 For sale by the Sul)rrintentlent of Documrnts. U.S. Gorernnient Printing Oficc* Washington, D.C. 20402 - Price $2.50 (cloth) Contents Joint Committee on the Library .................................... Library of Congress Trust Fund Board ............................... Forms of Gifts or Bequests to the Library of Congress .................. Officers of the Library ............................................ Consultants of the Library ......................................... Librarian's Liaison Committees ..................................... Organization Chart ............................................... Letter of Transmittal ............................................. Introduction ..................................................... 1 The Processing Department ..................................... 2 The Legislative Reference Service ................................ 3 The Reference Department ..................................... 4 The Law Library .............................................. 5 The Administrative Department ................................. 6 The Copyright Office .......................................... - Appendixes .4 1 Library of Congress Trust Fund Board. Summary of Annual -

7 4Th Annual Conf Ere Nee Proceedings

Di AMERICAN LIBRARY ASSOCIATION 7 4th Annual Confere nee Proceedings of the American Library Association At Philadelphia, Pennsylvania July 3-9, 1955 AMERICA LIBRARY ASSOCIATION 50 EAST HUROl'I STREET CHICAGO 11, ILLINOIS AMERICAN LIBRARY ASSOCIATION 74th Annual Con£ erence Proceedings of the American Library Association Philadelphia, Pennsylvania July 3-9, 1955 • AMERICAN LIBRARY ASSOCIATION 50 EAST HURON STREET CHICAGO 11, ILLINOIS 1955 ALA Conference Proceedings Philadelphia, Pennsylvania PRE-CONFERENCE INSTITUTES Audio-Visual Institute .................••.•••.............•....................• 1 Book Selection Work Conference ..••..•.•.•........................•....•........ 1 Board on Personnel Administration ..............................................• 2 Production and Promotion of Children's Books 3 GENERAL SESSIONS First General Session 4 Second General Session ...............•.•....................................... 5 Third General Session .............•.........•.•.•.......•..•..•........•.•.••.• 6 COUNCIL SESSIONS First Council Session .•.....•••.•••....••••••••.•..•..••.•••..•..•.•.•.••.•.•.••. 7 Second Council Session ................••.....................•................• 8 Third Council Session .......................................................... 23 DIVISIONS American Association of School Librarians . • . • . • . • . • • . • • . • . • 26 Association of College and Reference Libraries . • . • . • . • • • . • . • . 30 Cataloging and Classification, Division of • . • • . • . • • . • . • 34 Hospital Libraries Division.