Brilliant Beacons

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Research to Support Carrying Capacity Analysis at Boston Harbor Islands National Park Area

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Northeast Region Boston, Massachusetts Research to Support Carrying Capacity Analysis at Boston Harbor Islands National Park Area Technical Report NPS/NER/NRTR-2006/064 ON THE COVER Little Brewster Island Light Photograph by: William Valliere Research to Support Carrying Capacity Analysis at Boston Harbor Islands National Park Area Technical Report NPS/NER/NRTR-2006/064 Robert Manning Megha Budruk The University of Vermont Rubenstein School of Environment and Natural Resources Burlington, Vermont 05405 October 2006 U.S. Department of the Interior National Park Service Northeast Region Boston, Massachusetts The Northeast Region of the National Park Service (NPS) comprises national parks and related areas in 13 New England and Mid-Atlantic states. The diversity of parks and their resources are reflected in their designations as national parks, seashores, historic sites, recreation areas, military parks, memorials, and rivers and trails. Biological, physical, and social science research results, natural resource inventory and monitoring data, scientific literature reviews, bibliographies, and proceedings of technical workshops and conferences related to these park units are disseminated through the NPS/NER Technical Report (NRTR) and Natural Resources Report (NRR) series. The reports are a continuation of series with previous acronyms of NPS/PHSO, NPS/MAR, NPS/BSO-RNR and NPS/NERBOST. Individual parks may also disseminate information through their own report series. Natural Resources -

Historically Famous Lighthouses

HISTORICALLY FAMOUS LIGHTHOUSES CG-232 CONTENTS Foreword ALASKA Cape Sarichef Lighthouse, Unimak Island Cape Spencer Lighthouse Scotch Cap Lighthouse, Unimak Island CALIFORNIA Farallon Lighthouse Mile Rocks Lighthouse Pigeon Point Lighthouse St. George Reef Lighthouse Trinidad Head Lighthouse CONNECTICUT New London Harbor Lighthouse DELAWARE Cape Henlopen Lighthouse Fenwick Island Lighthouse FLORIDA American Shoal Lighthouse Cape Florida Lighthouse Cape San Blas Lighthouse GEORGIA Tybee Lighthouse, Tybee Island, Savannah River HAWAII Kilauea Point Lighthouse Makapuu Point Lighthouse. LOUISIANA Timbalier Lighthouse MAINE Boon Island Lighthouse Cape Elizabeth Lighthouse Dice Head Lighthouse Portland Head Lighthouse Saddleback Ledge Lighthouse MASSACHUSETTS Boston Lighthouse, Little Brewster Island Brant Point Lighthouse Buzzards Bay Lighthouse Cape Ann Lighthouse, Thatcher’s Island. Dumpling Rock Lighthouse, New Bedford Harbor Eastern Point Lighthouse Minots Ledge Lighthouse Nantucket (Great Point) Lighthouse Newburyport Harbor Lighthouse, Plum Island. Plymouth (Gurnet) Lighthouse MICHIGAN Little Sable Lighthouse Spectacle Reef Lighthouse Standard Rock Lighthouse, Lake Superior MINNESOTA Split Rock Lighthouse NEW HAMPSHIRE Isle of Shoals Lighthouse Portsmouth Harbor Lighthouse NEW JERSEY Navesink Lighthouse Sandy Hook Lighthouse NEW YORK Crown Point Memorial, Lake Champlain Portland Harbor (Barcelona) Lighthouse, Lake Erie Race Rock Lighthouse NORTH CAROLINA Cape Fear Lighthouse "Bald Head Light’ Cape Hatteras Lighthouse Cape Lookout Lighthouse. Ocracoke Lighthouse.. OREGON Tillamook Rock Lighthouse... RHODE ISLAND Beavertail Lighthouse. Prudence Island Lighthouse SOUTH CAROLINA Charleston Lighthouse, Morris Island TEXAS Point Isabel Lighthouse VIRGINIA Cape Charles Lighthouse Cape Henry Lighthouse WASHINGTON Cape Flattery Lighthouse Foreword Under the supervision of the United States Coast Guard, there is only one manned lighthouses in the entire nation. There are hundreds of other lights of varied description that are operated automatically. -

Great & Little Brewster

BOHA Terrestrial Vegetation and Intertidal Assemblages - DDRRAAFFTT Great Brewster Island and Little Brewster Island Green Island Mixed Brown Algae/Mytilus Reef Maritime Erosional Cliffs Outer Brewster Great Brewster Island Mixed Brown Algae/Semibalanus Calf Island Island Mixed Brown Algae/Semibalanus Tide Pool Middle Greater Brewster Island Brewster Island Recreational Little Brewster Mixed Assemblage MAP EXTENT Island Boston Harbor Staghorn Sumac Scrub Forest Early Successional Eastern Reed Marsh Woodland/Forest Other Urban Beach Strand or Build-up Mixed Brown Algae/ Northeastern Semibalanus/Green Algae Old Field High Intertidal Green Algae Overwash Dune Grassland Mixed Assemblage Beach High Intertidal Green Algae Green Crust Beach Tide Pool Semibalanus Mixed Brown Algae/Mytilus Reef No macrobiota Little Green Algae Other Urban Brewster Mixed Brown or Build-up Algae/Semibalanus/ Transition Zone Island Mytilus Reef Mytilus Reef Mixed Brown Mixed Assemblage Rock Algae/Mytilus Reef Green Crust Semibalanus Mixed Brown Mytilus Reef Mixed Assemblage Rock/Boulder - Algae/Semibalanus Mixed Zonation Beach Semibalanus Rock Maritime Rock Cliffs & Outcrops New England Rocky Intertidal Community Rock/Boulder - Mixed, No Zonation Rock/Boulder - Mixed Zonation Mixed Assemblage Beach 0 100 200 Meters $ Data Sources: NatureServe. 2009. Draft National Vegetation Classification Data (labeled in black); Bell, R.. 2003. BOHA Intertidal and Terrestrial Area Assessment (labeled in blue) Produced by the NPS FTSC at the University of Rhode Island 02 2010. -

Boston Harbor Islands National Park Area

Boston Harbor Islands National Park Area PHOTO: KEN MALLORY PHOTO: KEN MALLORY PHOTO: KEN MALLORY Peddocks Island Boston Harbor Boston Light looking toward Boston Harbor Over Hull and Worlds End looking back to Islands National Park Area Boston Harbor ollowing Professor E.O. Wilson’s March address to the Three rivers — the Charles, the Mystic, and the Neponset Massachusetts Land Trust meeting that drew attention — arranged like spokes on a wheel, feed into the harbor. Fto National Parks as corridors for preservation of The result: a network of urban estuaries where wildlife plant and animal species, a brief introduction to the Boston thrives, despite its proximity to one of the nation’s most Harbor National Park area seems all the more pertinent to populated metropolitan regions. Newton Conservators and their mandate to preserve open spaces. As the park opened for visitation this spring beginning May 13, ferryboats to Spectacle and Georges Island offered Designated a national park by an act of Congress in 1996, a first look at some of the harbor’s large variety of wildlife the 34 islands range in size from including migrating and resident less than one acre — Nixes Mate, birds. Then beginning in late The Graves, Shag Rocks, and June and running to Labor Day, Hangman — to Long Island’s 274 additional ferry service is available acres. All of the islands lie within to Bumpkin, Grape, Lovells, the large “C” shape of Boston and Peddocks, where overnight Harbor. The farthest island out, camping facilities are available. The Graves, sits 11 miles from shore. According to the park’s web site, the Massachusetts Natural Once an expanse of marshy plains Heritage Program lists six rare and elongated, gently sloping species known to exist within hills called drumlins, the basin PHOTO: KEN MALLORY the park, including two species containing the Boston Harbor listed as threatened and four Great Egret chicks on one of the harbor islands Islands National Park Area was of special concern. -

Add Boston Harbor Islands to Your (Beach) Search Bucket List This Summer ARCHIVES

SEARCH BUSINESS EAT & DRINK SPORTS THEATER & ARTS URBAN LIVING Add Boston Harbor Islands to Your (Beach) Search Bucket List this Summer ARCHIVES Tweet Posted May 19, 2015 by Cheryl Fenton in Downtown Boston April 2016 March 2016 When you think “island” in the summer, Martha’s February 2016 Like Vineyard and Nantucket come to mind. Then the January 2016 thought of Route 3 traffic quite literally stops you December 2015 in your tracks. What’s a sea lover to do? November 2015 There are plenty of water adventures to be had October 2015 closer to home. Enter the Boston Harbor Islands. September 2015 As the largest recreational open space in Eastern August 2015 Sunset over Boston from Lovells Island. Massachusetts, this system is made up of 34 July 2015 Photograph by Michael Greene islands and mainland parks. A half million of your June 2015 closest friends visit these islands every summer, May 2015 while a vast number of wildlife make it their year-round home. You can reach eight of these islands by Use our professional PDF creation service at http://www.htm2pdf.co.uk! seasonal ferryboat service (thank you, Boston Harbor Cruises), while 19 islands are accessed only by private boat or specialty charter. Three islands are a no-no for public visits. That’s OK. We didn’t want to visit those anyway. CATEGORIES The most well known of the Harbor Island is Georges Island, mostly due to it being the site of fort Warren, a Development & Real Estate historic battlement from the Civil War. The fort is said to be haunted by the Lady in Black. -

Sculptors Gallery Proudly Hosts “34,” a Group Exhibition Curated by Liz Devlin of FLUX

!"#$"% #&'()$"*# +,((-*. !"#$%&'"(!) *++, 486 Harrison Ave, Boston,."t ! XXXCPTUPOTDVMQUPSTDPNtCPTUPOTDVMQUPST!ZBIPPDPN FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE July 7, 2015 Exhibition Title: 34 Exhibition Dates: July 22 – August 16, 2015 Artists’ Reception: July 26 from 3 – 5 pm SOWA First Friday Reception: August 7 from 5 – 8 pm Gallery Hours: Wed. – Sun. from 12 – 6 pm (Boston, MA): As a part of the Isles Arts Initiative, a summer long public art series on the Boston Harbor Islands and in venues across Boston, the Boston Sculptors Gallery proudly hosts “34,” a group exhibition curated by Liz Devlin of FLUX. Boston Sculptors Gallery will showcase work inspired by the intrinsic beauty and divergent tales of the Boston Harbor Islands National and State Park. “34” is a group exhibition that includes 34 regional artists each responding to one of the 34 Boston Harbor Islands. Each imaginative work will be accompanied by a placard, featuring text from Chris Klein’s Discovering the Boston Harbor Islands, which outlines a brief history of the particular island and will provide additional context for the work itself. The exhibition serves as a physical beacon on land that will be in conversation with the artwork on the harbor. Artists’ work will educate and inspire visitors, sharing unique perspectives and visionary iconography that will demonstrate why the islands’ history is among the most fascinating in our region. About Boston Sculptors: Founded in 1992, Boston Sculptors Gallery is an artist-run organization that presents and promotes innovative, challenging sculpture and installations. It is the only sculptors organization in the United States that maintains its own exhibition space. The organization has presented exhibitions of its sculptors in other venues and countries and occasionally invites Curators to present exhibitions in its gallery in Boston’s South End. -

National Historic Lighthouse Preservation Act 2014 PROGRAM HIGHLIGHTS REPORT EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

GSA Office of Real Property Utilization and Disposal National Historic Lighthouse Preservation Act 2014 PROGRAM HIGHLIGHTS REPORT EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Lighthouses play an important role in America’s cultural For More Information: history, serving as aids to navigation (ATONs) for Information about specific lights in the NHLPA program is maritime vessels since before America’s founding. As a available at the following websites: way to preserve these pieces of our national heritage, Congress passed the National Historic Lighthouse National Park Service Lighthouse Heritage: Preservation Act (NHLPA) in 2000. The NHLPA http://www.nps.gov/maritime/nhlpa/intro.htm recognizes the importance of lighthouses and light General Services Administration Property Sales: stations (collectively called “lights”) to maritime traffic www.realestatesales.gov and the historical, cultural, recreational, and educational value of these iconic properties, especially for coastal communities and nonprofit organizations that serve as stewards who are dedicated to their continued Purpose of the Report: preservation. Through the NHLPA, Federal agencies, state and local governments, and not-for-profit This report outlines: organizations (non-profits) can obtain historic lights at no 1) The history of the NHLPA program; cost through stewardship transfers. If suitable public stewards are not found for a light, GSA will sell the light 2) The roles and responsibilities of the three Federal in a public auction (i.e., a public sale). Transfer deeds partner agencies executing the program; include covenants in the conveyance document to 3) Calendar Year1 2014 highlights and historical protect the light’s historic features and/or preserve disposal trends of the program; accessibility for the public. -

Celebrating 30 Years

VOLUME XXX NUMBER FOUR, 2014 Celebrating 30 Years •History of the U.S. Lighthouse Society •History of Fog Signals The•History Keeper’s of Log—Fall the U.S. 2014 Lighthouse Service •History of the Life-Saving Service 1 THE KEEPER’S LOG CELEBRATING 30 YEARS VOL. XXX NO. FOUR History of the United States Lighthouse Society 2 November 2014 The Founder’s Story 8 The Official Publication of the Thirty Beacons of Light 12 United States Lighthouse Society, A Nonprofit Historical & AMERICAN LIGHTHOUSE Educational Organization The History of the Administration of the USLH Service 23 <www.USLHS.org> By Wayne Wheeler The Keeper’s Log(ISSN 0883-0061) is the membership journal of the U.S. CLOCKWORKS Lighthouse Society, a resource manage- The Keeper’s New Clothes 36 ment and information service for people By Wayne Wheeler who care deeply about the restoration and The History of Fog Signals 42 preservation of the country’s lighthouses By Wayne Wheeler and lightships. Finicky Fog Bells 52 By Jeremy D’Entremont Jeffrey S. Gales – Executive Director The Light from the Whale 54 BOARD OF COMMISSIONERS By Mike Vogel Wayne C. Wheeler President Henry Gonzalez Vice-President OUR SISTER SERVICE RADM Bill Merlin Treasurer Through Howling Gale and Raging Surf 61 Mike Vogel Secretary By Dennis L. Noble Brian Deans Member U.S. LIGHTHOUSE SOCIETY DEPARTMENTS Tim Blackwood Member Ralph Eshelman Member Notice to Keepers 68 Ken Smith Member Thomas A. Tag Member THE KEEPER’S LOG STAFF Head Keep’—Wayne C. Wheeler Editor—Jeffrey S. Gales Production Editor and Graphic Design—Marie Vincent Copy Editor—Dick Richardson Technical Advisor—Thomas Tag The Keeper’s Log (ISSN 0883-0061) is published quarterly for $40 per year by the U.S. -

Junior Ranger Program Booklet (Camping Islands)

Boston Harbor Islands National Park Area Bumpkin Island Green Island Nixes Mate Sheep Island Button Island Hangman Island Nut Island Slate Island Calf Island Langlee Island Outer Brewster Island Snake Island Deer Island Little Brewster Island Peddocks Island Spectacle Island Gallops Island Little Calf Island Raccoon Island Thompson Island Georges Island Long Island Ragged Island Webb Memorial Park Grape Island Lovells Island Rainsford Island Worlds End The Graves Middle Brewster Island Sarah Island Great Brewster Island Moon Island Shag Rocks Can’t turn in this booklet in person? Make a copy of your Junior Ranger Program Booklet completed booklet and send it with your name and address to: Boston Harbor Islands Junior Ranger Program 15 State St. Suite 1100 Camping Islands Boston, MA 02109 Activities created by Elisabeth Colby Designed and illustrated by Liz Cook Union Park Press, proud supporters of the Boston Harbor Islands National Park and publishers of Discovering the Boston Harbor Islands: A Guide to the City's Hidden Shores. A of Map Boston Harbor JUNIORJUNIOR RANGERRANGER NATIONAL PARK AREA N H O A T R EAST BOSTON B S O O R B SNAKE ISLAND THE GRAVES DEER ISLAND I GREEN ISLAND S S L A N D BOSTON LITTLE CALF ISLAND OUTER BREWSTER ISLAND CALF ISLAND MIDDLE BREWSTER ISLAND NIXES MATE GREAT BREWSTER ISLAND LOVELLS ISLAND SHAG ROCKS LITTLE BREWSTER ISLAND As a SPECTACLE ISLAND GALLOPS ISLAND LONG ISLAND Junior Ranger, THOMPSON ISLAND GEORGES ISLAND RAINSFORD ISLAND I pledge to: MOON ISLAND PEDDOCKS ISLAND • Continue learning about the -

National Historic Landmark Nomination Cape Ann Light

NATIONAL HISTORIC LANDMARK NOMINATION NPS Form 10-900 USDI/NPS NRHP Registration Form (Rev. 8-86) OMB No. 1024-0018 CAPE ANN LIGHT STATION (Thacher Island Twin Lights) Page 1 United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form 1. NAME OF PROPERTY Historic Name: Cape Ann Light Station Other Name/Site Number: Thacher Island Twin Lights 2. LOCATION Street & Number: One mile off coast of Rockport, Massachusetts. Not for publication: City/Town: Rockport Vicinity: X State: MA County: Essex Code: 009 Zip Code: 01966 3. CLASSIFICATION Ownership of Property Category of Property Private: Building(s): Public-Local: X District: X Public-State: Site: Public-Federal: Structure: Object: Number of Resources within Property Contributing Noncontributing 4 buildings sites 2 2 structures objects 6 2 Total Number of Contributing Resources Previously Listed in the National Register: 6 Name of Related Multiple Property Listing: n/a (see summary context statement for Lighthouse NHL theme study) NATIONAL HISTORIC LANDMARK NOMINATION NPS Form 10-900 USDI/NPS NRHP Registration Form (Rev. 8-86) OMB No. 1024-0018 CAPE ANN LIGHT STATION (Thacher Island Twin Lights) Page 2 United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form 4. STATE/FEDERAL AGENCY CERTIFICATION As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, as amended, I hereby certify that this ____ nomination ____ request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. -

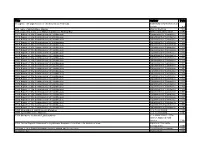

Lighthouse Bibliography.Pdf

Title Author Date 10 Lights: The Lighthouses of the Keweenaw Peninsula Keweenaw County Historical Society n.d. 100 Years of British Glass Making Chance Brothers 1924 137 Steps: The Story of St Mary's Lighthouse Whitley Bay North Tyneside Council 1999 1911 Report of the Commissioner of Lighthouses Department of Commerce 1911 1912 Report of the Commissioner of Lighthouses Department of Commerce 1912 1913 Report of the Commissioner of Lighthouses Department of Commerce 1913 1914 Report of the Commissioner of Lighthouses Department of Commerce 1914 1915 Report of the Commissioner of Lighthouses Department of Commerce 1915 1916 Report of the Commissioner of Lighthouses Department of Commerce 1916 1917 Report of the Commissioner of Lighthouses Department of Commerce 1917 1918 Report of the Commissioner of Lighthouses Department of Commerce 1918 1919 Report of the Commissioner of Lighthouses Department of Commerce 1919 1920 Report of the Commissioner of Lighthouses Department of Commerce 1920 1921 Report of the Commissioner of Lighthouses Department of Commerce 1921 1922 Report of the Commissioner of Lighthouses Department of Commerce 1922 1923 Report of the Commissioner of Lighthouses Department of Commerce 1923 1924 Report of the Commissioner of Lighthouses Department of Commerce 1924 1925 Report of the Commissioner of Lighthouses Department of Commerce 1925 1926 Report of the Commissioner of Lighthouses Department of Commerce 1926 1927 Report of the Commissioner of Lighthouses Department of Commerce 1927 1928 Report of the Commissioner of -

Fort Williams Projects Final Report

Fort Williams Projects Final Report Main Entrance Gate Interpretive Signs at Battery Knoll Bleachers Batteries Goddard Mansion March 26, 2009 35 Pleasant Street Architecture Portland, Maine 04101 Environmental Design 207.773.9699 Exhibit Design Fax 207.773.9599 Graphic Design [email protected] [email protected] To: Fort Williams Advisory Commission From: Richard Renner, Renner|Woodworth Date: March 26, 2009 Re: Fort Williams Projects – Final Report In early 2008, Renner|Woodworth, with its consultants Becker Structural Engineers and Stantec, were selected by the Town of Cape Elizabeth to assist the Fort Williams Advisory Commission with the following projects: Design and coordinate improvements to the main entrance; including new gates, fencing and stonewall reconstruction Design new interpretive/orientation signage to replace an existing panoramic display on Battery Knoll Assess the condition of the bleachers and develop options, and the associated costs for repair, replacement, and/or redevelopment Assess the condition of Goddard Mansion, develop options, and the associated costs for repair, restoration, and additional development Assess the condition of the batteries south of the access drive to Portland Head Light and develop options and the associated costs for repair, restoration, development, and interpretation The new entrance gate has been completed, and the new interpretive signs will be installed this spring, not at Battery Knoll, but at a higher location known as Kitty’s Point. This report focuses on the studies of the bleachers, Goddard Mansion, and the batteries. (Late in 2008, the team was also asked to assess the condition of Battery Keyes and to recommend measures to stabilize the structure and make it safer.