Arxiv:Astro-Ph/9905187V1 14 May 1999 Aacnrc a 5-26555

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mathématiques Et Espace

Atelier disciplinaire AD 5 Mathématiques et Espace Anne-Cécile DHERS, Education Nationale (mathématiques) Peggy THILLET, Education Nationale (mathématiques) Yann BARSAMIAN, Education Nationale (mathématiques) Olivier BONNETON, Sciences - U (mathématiques) Cahier d'activités Activité 1 : L'HORIZON TERRESTRE ET SPATIAL Activité 2 : DENOMBREMENT D'ETOILES DANS LE CIEL ET L'UNIVERS Activité 3 : D'HIPPARCOS A BENFORD Activité 4 : OBSERVATION STATISTIQUE DES CRATERES LUNAIRES Activité 5 : DIAMETRE DES CRATERES D'IMPACT Activité 6 : LOI DE TITIUS-BODE Activité 7 : MODELISER UNE CONSTELLATION EN 3D Crédits photo : NASA / CNES L'HORIZON TERRESTRE ET SPATIAL (3 ème / 2 nde ) __________________________________________________ OBJECTIF : Détermination de la ligne d'horizon à une altitude donnée. COMPETENCES : ● Utilisation du théorème de Pythagore ● Utilisation de Google Earth pour évaluer des distances à vol d'oiseau ● Recherche personnelle de données REALISATION : Il s'agit ici de mettre en application le théorème de Pythagore mais avec une vision terrestre dans un premier temps suite à un questionnement de l'élève puis dans un second temps de réutiliser la même démarche dans le cadre spatial de la visibilité d'un satellite. Fiche élève ____________________________________________________________________________ 1. Victor Hugo a écrit dans Les Châtiments : "Les horizons aux horizons succèdent […] : on avance toujours, on n’arrive jamais ". Face à la mer, vous voyez l'horizon à perte de vue. Mais "est-ce loin, l'horizon ?". D'après toi, jusqu'à quelle distance peux-tu voir si le temps est clair ? Réponse 1 : " Sans instrument, je peux voir jusqu'à .................. km " Réponse 2 : " Avec une paire de jumelles, je peux voir jusqu'à ............... km " 2. Nous allons maintenant calculer à l'aide du théorème de Pythagore la ligne d'horizon pour une hauteur H donnée. -

IRS Form 990PF for Vertex Foundation

2949115321712 8 7. Return of Private Foundation m- or Section 4947(a)(1) Trust Treated as Private Foundation De anmem ofme Treasury > Do not enter socIal securIty numbers on this form as It may be made publIc. Mirna, Revenue Senna; D Go to www.irs.gov/Form990PF for instructions and the latest information. I pen 0 u .5 n5 EC .0" For calendaryear 2017 or taxyear beginning OCT 11 , 2017 ,and ending DEC 31 , 2017 Name of loundaIIon A Employer identification number THE VERTEX FOUNDATION, INC. 82-3101518 Number and street (or P 0 box number It mall Is not delIvered to street address) Room/sune B Telephone number 50 NORTHERN AVENUE 617-961-5104 City or town, state or provmce, country, and ZIP 0f forelgn postal code c If exemptIon applIcatIon Is pendrng. check here > D U BOSTON, MA 02210 6 Check all that apply. lnItIal return I3 lnItIal return of a former pubIIc charIty D 1. ForeIgn organIzatIons, check here DE E] FInaI return E Amended return I3 Address change III Name change 2' SELEEggggggigiTngRngML >E] H Check type of organIzatIonz SectIon 501(c)(3) exempt prIvate foundatIon q E If prIvate toundatIon status was termInated [Z] SectIon 4947(a)(1) nonexempt charItable trust C] Other taxable prIvate foundatIon C under sectIon 507(b)(1)(A), check here D I I FaIr market value of all assets at end of year J AccountIng methodi El Cash Accrual F If the foundatIon IS In a 60-month termInatIon i (from Part II, col. (c), We 16) El Other (speCIfy) under sectIon 507(b)(1)(B), check here D b $ 6 2 4 , 6 0 2 . -

The Brightest Stars Seite 1 Von 9

The Brightest Stars Seite 1 von 9 The Brightest Stars This is a list of the 300 brightest stars made using data from the Hipparcos catalogue. The stellar distances are only fairly accurate for stars well within 1000 light years. 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 No. Star Names Equatorial Galactic Spectral Vis Abs Prllx Err Dist Coordinates Coordinates Type Mag Mag ly RA Dec l° b° 1. Alpha Canis Majoris Sirius 06 45 -16.7 227.2 -8.9 A1V -1.44 1.45 379.21 1.58 9 2. Alpha Carinae Canopus 06 24 -52.7 261.2 -25.3 F0Ib -0.62 -5.53 10.43 0.53 310 3. Alpha Centauri Rigil Kentaurus 14 40 -60.8 315.8 -0.7 G2V+K1V -0.27 4.08 742.12 1.40 4 4. Alpha Boötis Arcturus 14 16 +19.2 15.2 +69.0 K2III -0.05 -0.31 88.85 0.74 37 5. Alpha Lyrae Vega 18 37 +38.8 67.5 +19.2 A0V 0.03 0.58 128.93 0.55 25 6. Alpha Aurigae Capella 05 17 +46.0 162.6 +4.6 G5III+G0III 0.08 -0.48 77.29 0.89 42 7. Beta Orionis Rigel 05 15 -8.2 209.3 -25.1 B8Ia 0.18 -6.69 4.22 0.81 770 8. Alpha Canis Minoris Procyon 07 39 +5.2 213.7 +13.0 F5IV-V 0.40 2.68 285.93 0.88 11 9. Alpha Eridani Achernar 01 38 -57.2 290.7 -58.8 B3V 0.45 -2.77 22.68 0.57 144 10. -

GTO Keypad Manual, V5.001

ASTRO-PHYSICS GTO KEYPAD Version v5.xxx Please read the manual even if you are familiar with previous keypad versions Flash RAM Updates Keypad Java updates can be accomplished through the Internet. Check our web site www.astro-physics.com/software-updates/ November 11, 2020 ASTRO-PHYSICS KEYPAD MANUAL FOR MACH2GTO Version 5.xxx November 11, 2020 ABOUT THIS MANUAL 4 REQUIREMENTS 5 What Mount Control Box Do I Need? 5 Can I Upgrade My Present Keypad? 5 GTO KEYPAD 6 Layout and Buttons of the Keypad 6 Vacuum Fluorescent Display 6 N-S-E-W Directional Buttons 6 STOP Button 6 <PREV and NEXT> Buttons 7 Number Buttons 7 GOTO Button 7 ± Button 7 MENU / ESC Button 7 RECAL and NEXT> Buttons Pressed Simultaneously 7 ENT Button 7 Retractable Hanger 7 Keypad Protector 8 Keypad Care and Warranty 8 Warranty 8 Keypad Battery for 512K Memory Boards 8 Cleaning Red Keypad Display 8 Temperature Ratings 8 Environmental Recommendation 8 GETTING STARTED – DO THIS AT HOME, IF POSSIBLE 9 Set Up your Mount and Cable Connections 9 Gather Basic Information 9 Enter Your Location, Time and Date 9 Set Up Your Mount in the Field 10 Polar Alignment 10 Mach2GTO Daytime Alignment Routine 10 KEYPAD START UP SEQUENCE FOR NEW SETUPS OR SETUP IN NEW LOCATION 11 Assemble Your Mount 11 Startup Sequence 11 Location 11 Select Existing Location 11 Set Up New Location 11 Date and Time 12 Additional Information 12 KEYPAD START UP SEQUENCE FOR MOUNTS USED AT THE SAME LOCATION WITHOUT A COMPUTER 13 KEYPAD START UP SEQUENCE FOR COMPUTER CONTROLLED MOUNTS 14 1 OBJECTS MENU – HAVE SOME FUN! -

Educational Directory 1°30

UNITED STATESDEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR RAY LYMAN WILBUR. Secretary s. OFFICE OF EDUCATION WILLIAM JOHN COOPER. Commissioner BULLETIN, 1930, No. 1 EDUCATIONAL DIRECTORY 1°30 1 --"16. ,0 DANIA el 9-111911,- , Al.. s."2:1,_ 111 %. a a. Al. UNITED STATES GOVEANNIENT PRINTING OFFICE WASHINGTON:1930 - bes oh by the Swerintendept ofDocuments, Yashington, D. C. e . Price 30 casts o ) ..:41 1\1 456391 g. JUrl-71118 AC4 1,69 \ '30 ,1101141117111.... swim r-" R :7) - - -.40- - t .1.111= CONTENTS I 1 Page I. United StatesOffice ofEducation___ _ _ 1 II. PrincipalState schoolofficers .. ______ .. ... s .;2 III. Countyand other localsuperintendents of schools'_ _...... _ .............. 16 Iv. Superintendentsof public schoolsin cities andtowns 40 I V. Public-schoolbusiness managers_______- ____---.--..... --- 57, VI. Presidentsof tiniversitiesand colleges 58 VII. Presidents of juniorcolleges _ , 65 VIII. Headsof departmentsof education_ 68 "P r Ix. Presidentsor WM OW .N. deans of sehoolsof theology__ m =0 MMM .. ../ Mt o. w l0 X. Presidentsordeans of schools oflaw _ 78 XI. Presidentsor deans of schools of medicinP M Mo". wt. MP OM mm .. 80 XII. Presidentsordeans of schoolsof dentistry__.---- ___--- - 82 XIII. Prusidentsordeans of dchoolsof pharmacy_____ .. 82 XIV. PNsidentsofrschools ofosteopathy : 84 XV. Deansof schools ofveterinary medicine . 84 XVI. Deansof collegiateschools ofcommerce 84 XVII. Schools, colleges,ordepartments ofengineering _ 86 XVIII. Presidents,etc., of institutions forthetraini;igof teachers: , (1) Presidents ofteachers colleges__:__aft do am IND . _ . _ 89 (2) Principals of Statenormal schools_______ _ N.M4, 91 (3) Principals ofcity public normalschools___ __ _ 92 (4) Principals ofprivate physicaltraining schoolss.,__ _ 92 (5) Prinoipals ofprivatenursery,kindergarten, andprimary training schools 93 (6) Principals of privategeneral training schools 93 XIX. -

Abstract Bookletbooklet

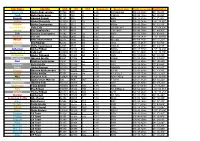

ABSTRACTABSTRACT BOOKLETBOOKLET PlanetPlanet FormationFormation && EvolutionEvolution 20142014 Kiel University, September 8 - 10, 2014 Scientific Rationale The goal of this workshop is to provide a common platform for scientists working in the fields of star and planet formation, exo-planets, astrobiology, and planetary research in general. Most importantly, this workshop aims to stimulate and intensify the dialogue between researchers using various approaches - observations, theory, and laboratory studies. Students and Postdocs are particularly encouraged to present their results and to use the opportunity to learn more about the main questions and most recent results in adjacent fields. www.astrophysik.uni-kiel.de/kiel2014 Contact: [email protected] Foto/Copyright: Czeslaw Martysz Planet Formation & Evolution 2014 8 - 10 September 2014 { Kiel Abstracts [updated: August 25, 2014] Scientific Organization Committee Local Organization Committee Sebastian Wolf (Chair, Universit¨atKiel) Jan Philipp Ruge (Chair) J¨urgenBlum (Universit¨atBraunschweig) Gesa Bertrang Stephan Dreizler (Universit¨atG¨ottingen) Robert Brunngr¨aber Barbara Ercolano (Universit¨atM¨unchen) Florian Kirchschlager Artie Hatzes (Th¨uringerLandessternwarte, Tautenburg) Brigitte Kuhr Willy Kley (Universit¨atT¨ubingen) Florian Ober Thomas Preibisch (Universit¨atM¨unchen) Stefan Reißl Heike Rauer (DLR, Berlin) Peter Scicluna Mario Trieloff (Universit¨atHeidelberg) Sebastian Wolf Robert Wimmer-Schweingruber (Universit¨atKiel) Gerhard Wurm (Universit¨atDuisburg) -

1455189355674.Pdf

THE STORYTeller’S THESAURUS FANTASY, HISTORY, AND HORROR JAMES M. WARD AND ANNE K. BROWN Cover by: Peter Bradley LEGAL PAGE: Every effort has been made not to make use of proprietary or copyrighted materi- al. Any mention of actual commercial products in this book does not constitute an endorsement. www.trolllord.com www.chenaultandgraypublishing.com Email:[email protected] Printed in U.S.A © 2013 Chenault & Gray Publishing, LLC. All Rights Reserved. Storyteller’s Thesaurus Trademark of Cheanult & Gray Publishing. All Rights Reserved. Chenault & Gray Publishing, Troll Lord Games logos are Trademark of Chenault & Gray Publishing. All Rights Reserved. TABLE OF CONTENTS THE STORYTeller’S THESAURUS 1 FANTASY, HISTORY, AND HORROR 1 JAMES M. WARD AND ANNE K. BROWN 1 INTRODUCTION 8 WHAT MAKES THIS BOOK DIFFERENT 8 THE STORYTeller’s RESPONSIBILITY: RESEARCH 9 WHAT THIS BOOK DOES NOT CONTAIN 9 A WHISPER OF ENCOURAGEMENT 10 CHAPTER 1: CHARACTER BUILDING 11 GENDER 11 AGE 11 PHYSICAL AttRIBUTES 11 SIZE AND BODY TYPE 11 FACIAL FEATURES 12 HAIR 13 SPECIES 13 PERSONALITY 14 PHOBIAS 15 OCCUPATIONS 17 ADVENTURERS 17 CIVILIANS 18 ORGANIZATIONS 21 CHAPTER 2: CLOTHING 22 STYLES OF DRESS 22 CLOTHING PIECES 22 CLOTHING CONSTRUCTION 24 CHAPTER 3: ARCHITECTURE AND PROPERTY 25 ARCHITECTURAL STYLES AND ELEMENTS 25 BUILDING MATERIALS 26 PROPERTY TYPES 26 SPECIALTY ANATOMY 29 CHAPTER 4: FURNISHINGS 30 CHAPTER 5: EQUIPMENT AND TOOLS 31 ADVENTurer’S GEAR 31 GENERAL EQUIPMENT AND TOOLS 31 2 THE STORYTeller’s Thesaurus KITCHEN EQUIPMENT 35 LINENS 36 MUSICAL INSTRUMENTS -

Star Name Identity SAO HD FK5 Magnitude Spectral Class Right Ascension Declination Alpheratz Alpha Andromedae 73765 358 1 2,06 B

Star Name Identity SAO HD FK5 Magnitude Spectral class Right ascension Declination Alpheratz Alpha Andromedae 73765 358 1 2,06 B8IVpMnHg 00h 08,388m 29° 05,433' Caph Beta Cassiopeiae 21133 432 2 2,27 F2III-IV 00h 09,178m 59° 08,983' Algenib Gamma Pegasi 91781 886 7 2,83 B2IV 00h 13,237m 15° 11,017' Ankaa Alpha Phoenicis 215093 2261 12 2,39 K0III 00h 26,283m - 42° 18,367' Schedar Alpha Cassiopeiae 21609 3712 21 2,23 K0IIIa 00h 40,508m 56° 32,233' Deneb Kaitos Beta Ceti 147420 4128 22 2,04 G9.5IIICH-1 00h 43,590m - 17° 59,200' Achird Eta Cassiopeiae 21732 4614 3,44 F9V+dM0 00h 49,100m 57° 48,950' Tsih Gamma Cassiopeiae 11482 5394 32 2,47 B0IVe 00h 56,708m 60° 43,000' Haratan Eta ceti 147632 6805 40 3,45 K1 01h 08,583m - 10° 10,933' Mirach Beta Andromedae 54471 6860 42 2,06 M0+IIIa 01h 09,732m 35° 37,233' Alpherg Eta Piscium 92484 9270 50 3,62 G8III 01h 13,483m 15° 20,750' Rukbah Delta Cassiopeiae 22268 8538 48 2,66 A5III-IV 01h 25,817m 60° 14,117' Achernar Alpha Eridani 232481 10144 54 0,46 B3Vpe 01h 37,715m - 57° 14,200' Baten Kaitos Zeta Ceti 148059 11353 62 3,74 K0IIIBa0.1 01h 51,460m - 10° 20,100' Mothallah Alpha Trianguli 74996 11443 64 3,41 F6IV 01h 53,082m 29° 34,733' Mesarthim Gamma Arietis 92681 11502 3,88 A1pSi 01h 53,530m 19° 17,617' Navi Epsilon Cassiopeiae 12031 11415 63 3,38 B3III 01h 54,395m 63° 40,200' Sheratan Beta Arietis 75012 11636 66 2,64 A5V 01h 54,640m 20° 48,483' Risha Alpha Piscium 110291 12447 3,79 A0pSiSr 02h 02,047m 02° 45,817' Almach Gamma Andromedae 37734 12533 73 2,26 K3-IIb 02h 03,900m 42° 19,783' Hamal Alpha -

DUMMY EGGS by Mick Bassett (Germany)

VARIOUS February 2015 Part 1b For next or previous screen: use the mouse wheel, or Pg Up and Pg Dn or ↑ and ↓ on your keyboard. CONSTELLATION COLUMBA Did you know there is also a constellation named Columba, which name is Latin for dove? Columba is a small, faint constellation created in the late sixteenth century. It is located just south of Canis Major and Lepus. Columba was created in 1592 by the Flemish astronomer Petrus Plancius, who was also cartographer, one of the founders of the Dutch East India Company and clergyman. He named the constellation Columba Noachi (Noah's Dove), referring to the dove that gave Noah the information that the Great Flood was receding. The names of Plancius's constellations are mostly referring to animals and subjects described in natural history books and travellers' journals of his day. Columba was first shown as a separate constellation in 1592 on a celestial hemisphere that Plancius tucked into the corner of his first great terrestrial map. It flies behind Argo Navis, the ship. To complete this Biblical tableau, Plancius even renamed Argo as Noah’s Ark on a globe of 1613. However, those familiar with the story of Argo might instead think of Columba as the dove sent by the Argonauts between the sliding doors of the Clashing Rocks to ensure their safe passage. The constellation’s brightest s t a r, third- magnitude Alpha Columbae, is called Phact, from an Arabic name meaning ‘ring dove’. With our thanks to Ian Ridpath, Startales, http://www.ianridpath.com/ Illustration: Columba with an olive branch in its beak as shown in the Uranographia of Johann Bode (1801). -

Brightest Stars : Discovering the Universe Through the Sky's Most Brilliant Stars / Fred Schaaf

ffirs.qxd 3/5/08 6:26 AM Page i THE BRIGHTEST STARS DISCOVERING THE UNIVERSE THROUGH THE SKY’S MOST BRILLIANT STARS Fred Schaaf John Wiley & Sons, Inc. flast.qxd 3/5/08 6:28 AM Page vi ffirs.qxd 3/5/08 6:26 AM Page i THE BRIGHTEST STARS DISCOVERING THE UNIVERSE THROUGH THE SKY’S MOST BRILLIANT STARS Fred Schaaf John Wiley & Sons, Inc. ffirs.qxd 3/5/08 6:26 AM Page ii This book is dedicated to my wife, Mamie, who has been the Sirius of my life. This book is printed on acid-free paper. Copyright © 2008 by Fred Schaaf. All rights reserved Published by John Wiley & Sons, Inc., Hoboken, New Jersey Published simultaneously in Canada Illustration credits appear on page 272. Design and composition by Navta Associates, Inc. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, scanning, or otherwise, except as permitted under Section 107 or 108 of the 1976 United States Copyright Act, without either the prior written permission of the Publisher, or authorization through payment of the appropriate per-copy fee to the Copyright Clearance Center, 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923, (978) 750-8400, fax (978) 646-8600, or on the web at www.copy- right.com. Requests to the Publisher for permission should be addressed to the Permissions Department, John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 111 River Street, Hoboken, NJ 07030, (201) 748-6011, fax (201) 748-6008, or online at http://www.wiley.com/go/permissions. -

The COLOUR of CREATION Observing and Astrophotography Targets “At a Glance” Guide

The COLOUR of CREATION observing and astrophotography targets “at a glance” guide. (Naked eye, binoculars, small and “monster” scopes) Dear fellow amateur astronomer. Please note - this is a work in progress – compiled from several sources - and undoubtedly WILL contain inaccuracies. It would therefor be HIGHLY appreciated if readers would be so kind as to forward ANY corrections and/ or additions (as the document is still obviously incomplete) to: [email protected]. The document will be updated/ revised/ expanded* on a regular basis, replacing the existing document on the ASSA Pretoria website, as well as on the website: coloursofcreation.co.za . This is by no means intended to be a complete nor an exhaustive listing, but rather an “at a glance guide” (2nd column), that will hopefully assist in choosing or eliminating certain objects in a specific constellation for further research, to determine suitability for observation or astrophotography. There is NO copy right - download at will. Warm regards. JohanM. *Edition 1: June 2016 (“Pre-Karoo Star Party version”). “To me, one of the wonders and lures of astronomy is observing a galaxy… realizing you are detecting ancient photons, emitted by billions of stars, reduced to a magnitude below naked eye detection…lying at a distance beyond comprehension...” ASSA 100. (Auke Slotegraaf). Messier objects. Apparent size: degrees, arc minutes, arc seconds. Interesting info. AKA’s. Emphasis, correction. Coordinates, location. Stars, star groups, etc. Variable stars. Double stars. (Only a small number included. “Colourful Ds. descriptions” taken from the book by Sissy Haas). Carbon star. C Asterisma. (Including many “Streicher” objects, taken from Asterism. -

INDIAN INSTITUTE of ASTROPHYSICS Annual Report 1989-90

INDIAN INSTITUTE OF ASTROPHYSICS Annual Report 1989-90 Front Cover (inset) : Aerial view of IIA, Bangalore Cover photo & design : Pankaj Shah Edited by M. Parthasarathy & S. S. Hasan Produced by S. S. Hasan Printed at Vykat Prints, Bangalore-560 017 Contents Page Governing Council ....................................... ..- .......... v The Year in Review 1 Research Highlights 3 Solar Physics 5 Velocity fields 5 Chromosphere 9 Corona 9 Magnetic fields 10 Miscellaneous 14 Solar System 17 Comets 17 Asteroids 17 Planets and Satellites 18 Star/Solar system formation ................................. 19 Stellar Physics ............................................... 21 Novae and Supernovae ..................................... 21 Be Stars .................................................. 21 General 22 Supergiants 25 Star clusters 29 Radiative transfer and Scattering ............................. 30 Interstellar Medium and Planetary Nebulae ........................ 35 Pulsars 35 Symbiotic stars and Planetary nebulae ......................... 35 Galaxies, High Energy Astrophysics and Cosmology ............... 37 Galaxies 37 Quasars 38 Solar Terrestrial Physics Ionosphere . 43 Geomagnetic phenomena 45 Instrumentation 47 Computer facility .......................................... 47 CCD system .......................................... , ... 47 Data acquisition/processing system ............................ 47 System performance of the telescopes ......................... 49 Radio telescopes 49 Auxiliary instruments 50 Optics division 51 Mechanical