Gut Microbiota Modulation of Chemotherapy Efficacy and Toxicity

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Role of Earthworm Gut-Associated Microorganisms in the Fate of Prions in Soil

THE ROLE OF EARTHWORM GUT-ASSOCIATED MICROORGANISMS IN THE FATE OF PRIONS IN SOIL Von der Fakultät für Lebenswissenschaften der Technischen Universität Carolo-Wilhelmina zu Braunschweig zur Erlangung des Grades eines Doktors der Naturwissenschaften (Dr. rer. nat.) genehmigte D i s s e r t a t i o n von Taras Jur’evič Nechitaylo aus Krasnodar, Russland 2 Acknowledgement I would like to thank Prof. Dr. Kenneth N. Timmis for his guidance in the work and help. I thank Peter N. Golyshin for patience and strong support on this way. Many thanks to my other colleagues, which also taught me and made the life in the lab and studies easy: Manuel Ferrer, Alex Neef, Angelika Arnscheidt, Olga Golyshina, Tanja Chernikova, Christoph Gertler, Agnes Waliczek, Britta Scheithauer, Julia Sabirova, Oleg Kotsurbenko, and other wonderful labmates. I am also grateful to Michail Yakimov and Vitor Martins dos Santos for useful discussions and suggestions. I am very obliged to my family: my parents and my brother, my parents on low and of course to my wife, which made all of their best to support me. 3 Summary.....................................................………………………………………………... 5 1. Introduction...........................................................................................................……... 7 Prion diseases: early hypotheses...………...………………..........…......…......……….. 7 The basics of the prion concept………………………………………………….……... 8 Putative prion dissemination pathways………………………………………….……... 10 Earthworms: a putative factor of the dissemination of TSE infectivity in soil?.………. 11 Objectives of the study…………………………………………………………………. 16 2. Materials and Methods.............................…......................................................……….. 17 2.1 Sampling and general experimental design..................................................………. 17 2.2 Fluorescence in situ Hybridization (FISH)………..……………………….………. 18 2.2.1 FISH with soil, intestine, and casts samples…………………………….……... 18 Isolation of cells from environmental samples…………………………….………. -

Pharmacomicrobiomics: a Novel Route Towards Personalized Medicine?

Protein Cell 2018, 9(5):432–445 https://doi.org/10.1007/s13238-018-0547-2 Protein & Cell REVIEW Pharmacomicrobiomics: a novel route towards personalized medicine? Marwah Doestzada1,2, Arnau Vich Vila1,3, Alexandra Zhernakova1, Debby P. Y. Koonen2, Rinse K. Weersma3, Daan J. Touw4, Folkert Kuipers2,5, Cisca Wijmenga1,6, Jingyuan Fu1,2& 1 Departments of Genetics, University Medical Center Groningen, PO Box 30001, 9700 RB Groningen, The Netherlands 2 Departments of Paediatrics, University Medical Center Groningen, PO Box 30001, 9700 RB Groningen, The Netherlands 3 Departments of Gastroenterology & Hepatology, University Medical Center Groningen, PO Box 30001, 9700 RB Groningen, The Netherlands 4 Departments of Clinical Pharmacy & Pharmacology, University Medical Center Groningen, PO Box 30001, 9700 RB Groningen, The Netherlands Cell 5 Departments of Laboratory Medicine, University Medical Center Groningen, PO Box 30001, 9700 RB Groningen, & The Netherlands 6 K.G. Jebsen Coeliac Disease Research Centre, Department of Immunology, University of Oslo, P.O. Box 1072, Blindern, 0316 Oslo, Norway & Correspondence: [email protected] (J. Fu) Received March 5, 2018 Accepted April 16, 2018 Protein ABSTRACT INTRODUCTION Inter-individual heterogeneity in drug response is a Individual responses to a specific drug vary greatly in terms serious problem that affects the patient’s wellbeing and of both efficacy and toxicity. It has been reported that poses enormous clinical and financial burdens on a response rates to common drugs for the treatment of a wide societal level. Pharmacogenomics has been at the variety of diseases fall typically in the range of 50%–75%, forefront of research into the impact of individual indicating that up to half of patients are seeing no benefit genetic background on drug response variability or drug (Spear et al., 2001). -

Species Determination – What's in My Sample?

Species determination – what’s in my sample? What is my sample? • When might you not know what your sample is? • One species • You have a malaria sample but don’t know which species • Misidentification or no identification from culture/MALDI-TOF • Metagenomic samples • Contamination Taxonomic Classifiers • Compare sequence reads against a database and determine the species • BLAST works for a single sequence, too slow for a whole run • Classifiers use database indexing and k-mer searching • Similar accuracy to BLAST but much much faster Wood and Salzberg Genome Biology 2014, 15:R46 Page 3 of 12 http://genomebiology.com/2014/15/3/R46 Kraken taxonomic classifier Figure 1 The Kraken sequence classification algorithm. To classify a sequence, each k-mer in the sequence is mapped to the lowest common ancestor (LCA) of the genomes that contain that k-mer in a database. The taxa associated with the sequence’s k-mers, as well as the taxa’s ancestors, form a pruned subtree of the general taxonomy tree, which is used for classification. In the classification tree, each node has a 15 weight equal to the number of k-mersWood in the and sequence Salzberg associatedGenome with the Biology node’s taxon. 2014 Each root-to-leaf:R46 (RTL) path in the classification tree is scored by adding all weights in the path, and the maximal RTL path in the classification tree is the classification path (nodes highlighted in yellow). The leaf of this classification path (the orange, leftmost leaf in the classification tree) is the classification used for the query sequence. -

The Mysterious Orphans of Mycoplasmataceae

The mysterious orphans of Mycoplasmataceae Tatiana V. Tatarinova1,2*, Inna Lysnyansky3, Yuri V. Nikolsky4,5,6, and Alexander Bolshoy7* 1 Children’s Hospital Los Angeles, Keck School of Medicine, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, 90027, California, USA 2 Spatial Science Institute, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, 90089, California, USA 3 Mycoplasma Unit, Division of Avian and Aquatic Diseases, Kimron Veterinary Institute, POB 12, Beit Dagan, 50250, Israel 4 School of Systems Biology, George Mason University, 10900 University Blvd, MSN 5B3, Manassas, VA 20110, USA 5 Biomedical Cluster, Skolkovo Foundation, 4 Lugovaya str., Skolkovo Innovation Centre, Mozhajskij region, Moscow, 143026, Russian Federation 6 Vavilov Institute of General Genetics, Moscow, Russian Federation 7 Department of Evolutionary and Environmental Biology and Institute of Evolution, University of Haifa, Israel 1,2 [email protected] 3 [email protected] 4-6 [email protected] 7 [email protected] 1 Abstract Background: The length of a protein sequence is largely determined by its function, i.e. each functional group is associated with an optimal size. However, comparative genomics revealed that proteins’ length may be affected by additional factors. In 2002 it was shown that in bacterium Escherichia coli and the archaeon Archaeoglobus fulgidus, protein sequences with no homologs are, on average, shorter than those with homologs [1]. Most experts now agree that the length distributions are distinctly different between protein sequences with and without homologs in bacterial and archaeal genomes. In this study, we examine this postulate by a comprehensive analysis of all annotated prokaryotic genomes and focusing on certain exceptions. -

MIB–MIP Is a Mycoplasma System That Captures and Cleaves Immunoglobulin G

MIB–MIP is a mycoplasma system that captures and cleaves immunoglobulin G Yonathan Arfia,b,1, Laetitia Minderc,d, Carmelo Di Primoe,f,g, Aline Le Royh,i,j, Christine Ebelh,i,j, Laurent Coquetk, Stephane Claveroll, Sanjay Vasheem, Joerg Joresn,o, Alain Blancharda,b, and Pascal Sirand-Pugneta,b aINRA (Institut National de la Recherche Agronomique), UMR 1332 Biologie du Fruit et Pathologie, F-33882 Villenave d’Ornon, France; bUniversity of Bordeaux, UMR 1332 Biologie du Fruit et Pathologie, F-33882 Villenave d’Ornon, France; cInstitut Européen de Chimie et Biologie, UMS 3033, University of Bordeaux, 33607 Pessac, France; dInstitut Bergonié, SIRIC BRIO, 33076 Bordeaux, France; eINSERM U1212, ARN Regulation Naturelle et Artificielle, 33607 Pessac, France; fCNRS UMR 5320, ARN Regulation Naturelle et Artificielle, 33607 Pessac, France; gInstitut Européen de Chimie et Biologie, University of Bordeaux, 33607 Pessac, France; hInstitut de Biologie Structurale, University of Grenoble Alpes, F-38044 Grenoble, France; iCNRS, Institut de Biologie Structurale, F-38044 Grenoble, France; jCEA, Institut de Biologie Structurale, F-38044 Grenoble, France; kCNRS UMR 6270, Plateforme PISSARO, Institute for Research and Innovation in Biomedicine - Normandie Rouen, Normandie Université, F-76821 Mont-Saint-Aignan, France; lProteome Platform, Functional Genomic Center of Bordeaux, University of Bordeaux, F-33076 Bordeaux Cedex, France; mJ. Craig Venter Institute, Rockville, MD 20850; nInternational Livestock Research Institute, 00100 Nairobi, Kenya; and oInstitute of Veterinary Bacteriology, University of Bern, CH-3001 Bern, Switzerland Edited by Roy Curtiss III, University of Florida, Gainesville, FL, and approved March 30, 2016 (received for review January 12, 2016) Mycoplasmas are “minimal” bacteria able to infect humans, wildlife, introduced into naive herds (8). -

Pharmacogenetic Testing: a Tool for Personalized Drug Therapy Optimization

pharmaceutics Review Pharmacogenetic Testing: A Tool for Personalized Drug Therapy Optimization Kristina A. Malsagova 1,* , Tatyana V. Butkova 1 , Arthur T. Kopylov 1 , Alexander A. Izotov 1, Natalia V. Potoldykova 2, Dmitry V. Enikeev 2, Vagarshak Grigoryan 2, Alexander Tarasov 3, Alexander A. Stepanov 1 and Anna L. Kaysheva 1 1 Biobanking Group, Branch of Institute of Biomedical Chemistry “Scientific and Education Center”, 109028 Moscow, Russia; [email protected] (T.V.B.); [email protected] (A.T.K.); [email protected] (A.A.I.); [email protected] (A.A.S.); [email protected] (A.L.K.) 2 Institute of Urology and Reproductive Health, Sechenov University, 119992 Moscow, Russia; [email protected] (N.V.P.); [email protected] (D.V.E.); [email protected] (V.G.) 3 Institute of Linguistics and Intercultural Communication, Sechenov University, 119992 Moscow, Russia; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +7-499-764-9878 Received: 2 November 2020; Accepted: 17 December 2020; Published: 19 December 2020 Abstract: Pharmacogenomics is a study of how the genome background is associated with drug resistance and how therapy strategy can be modified for a certain person to achieve benefit. The pharmacogenomics (PGx) testing becomes of great opportunity for physicians to make the proper decision regarding each non-trivial patient that does not respond to therapy. Although pharmacogenomics has become of growing interest to the healthcare market during the past five to ten years the exact mechanisms linking the genetic polymorphisms and observable responses to drug therapy are not always clear. Therefore, the success of PGx testing depends on the physician’s ability to understand the obtained results in a standardized way for each particular patient. -

Genomic Islands in Mycoplasmas

G C A T T A C G G C A T genes Review Genomic Islands in Mycoplasmas Christine Citti * , Eric Baranowski * , Emilie Dordet-Frisoni, Marion Faucher and Laurent-Xavier Nouvel Interactions Hôtes-Agents Pathogènes (IHAP), Université de Toulouse, INRAE, ENVT, 31300 Toulouse, France; [email protected] (E.D.-F.); [email protected] (M.F.); [email protected] (L.-X.N.) * Correspondence: [email protected] (C.C.); [email protected] (E.B.) Received: 30 June 2020; Accepted: 20 July 2020; Published: 22 July 2020 Abstract: Bacteria of the Mycoplasma genus are characterized by the lack of a cell-wall, the use of UGA as tryptophan codon instead of a universal stop, and their simplified metabolic pathways. Most of these features are due to the small-size and limited-content of their genomes (580–1840 Kbp; 482–2050 CDS). Yet, the Mycoplasma genus encompasses over 200 species living in close contact with a wide range of animal hosts and man. These include pathogens, pathobionts, or commensals that have retained the full capacity to synthesize DNA, RNA, and all proteins required to sustain a parasitic life-style, with most being able to grow under laboratory conditions without host cells. Over the last 10 years, comparative genome analyses of multiple species and strains unveiled some of the dynamics of mycoplasma genomes. This review summarizes our current knowledge of genomic islands (GIs) found in mycoplasmas, with a focus on pathogenicity islands, integrative and conjugative elements (ICEs), and prophages. Here, we discuss how GIs contribute to the dynamics of mycoplasma genomes and how they participate in the evolution of these minimal organisms. -

Characterization of the Bacterial Communities of the Tonsil of the Soft Palate of Swine

Characterization of the Bacterial Communities of the Tonsil of the Soft Palate of Swine by Shaun Kernaghan A Thesis Presented to The University of Guelph In partial fulfilment of requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Pathobiology Guelph, Ontario, Canada © Shaun Kernaghan, December, 2013 ABSTRACT CHARACTERIZATION OF THE BACTERIAL COMMUNITIES OF THE TONSIL OF THE SOFT PALATE OF SWINE Shaun Kernaghan Advisor: University of Guelph, 2013 Professor Janet I. MacInnes Terminal restriction fragment length polymorphism (T-RFLP) analysis and pyrosequencing were used to characterize the microbiota of the tonsil of the soft palate of 126 unfit and 18 healthy pigs. The T-RFLP analysis method was first optimized for the study of the pig tonsil microbiota and the data compared with culture-based identification of common pig pathogens. Putative identifications of the members of the microbiota revealed that the phyla Firmicutes, Proteobacteria and Bacteroidetes were the most prevalent. A comparison of the T-RFLP analysis results grouped into clusters to clinical conditions revealed paleness, abscess, PRRS virus, and Mycoplasma hyopneumoniae to be significantly associated with cluster membership. T-RFLP analysis was also used to select representative tonsil samples for pyrosequencing. These studies confirmed Actinobacteria, Bacteroidetes, Firmicutes, Fusobacteria, and Proteobacteria to be the core phyla of the microbiota of the tonsil of the soft palate of pigs. Acknowledgements I would like to thank my advisor Janet MacInnes for her support and endless patience during this project. I would like to thank my committee, Patrick Boerlin and Emma Allen-Vercoe, for their insights and support, as well as Zvoninir Poljak for his help through this project. -

Effectors of Mycoplasmal Virulence 1 2 Virulence Effectors of Pathogenic Mycoplasmas 3 4 Meghan A. May1 And

Preprints (www.preprints.org) | NOT PEER-REVIEWED | Posted: 27 September 2018 doi:10.20944/preprints201809.0533.v1 1 Running title: Effectors of mycoplasmal virulence 2 3 Virulence Effectors of Pathogenic Mycoplasmas 4 5 Meghan A. May1 and Daniel R. Brown2 6 7 1Department of Biomedical Sciences, College of Osteopathic Medicine, University of New 8 England, Biddeford ME, USA; 2Department of Infectious Diseases and Immunology, College 9 of Veterinary Medicine, University of Florida, Gainesville FL, USA 10 11 Corresponding author: 12 Daniel R. Brown 13 Department of Infectious Diseases and Immunology, College of Veterinary Medicine, 14 University of Florida, Gainesville FL, USA 15 Tel: +1 352 294 4004 16 Email: [email protected] 1 © 2018 by the author(s). Distributed under a Creative Commons CC BY license. Preprints (www.preprints.org) | NOT PEER-REVIEWED | Posted: 27 September 2018 doi:10.20944/preprints201809.0533.v1 17 Abstract 18 Members of the genus Mycoplasma and related organisms impose a substantial burden of 19 infectious diseases on humans and animals, but the last comprehensive review of 20 mycoplasmal pathogenicity was published 20 years ago. Post-genomic analyses have now 21 begun to support the discovery and detailed molecular biological characterization of a 22 number of specific mycoplasmal virulence factors. This review covers three categories of 23 defined mycoplasmal virulence effectors: 1) specific macromolecules including the 24 superantigen MAM, the ADP-ribosylating CARDS toxin, sialidase, cytotoxic nucleases, cell- 25 activating diacylated lipopeptides, and phosphocholine-containing glycoglycerolipids; 2) 26 the small molecule effectors hydrogen peroxide, hydrogen sulfide, and ammonia; and 3) 27 several putative mycoplasmal orthologs of virulence effectors documented in other 28 bacteria. -

1.11 Antidepressants and the Gut Microbiota

UCC Library and UCC researchers have made this item openly available. Please let us know how this has helped you. Thanks! Title Effects of psychotropic drugs on the microbiota-gut-liver-brain axis Author(s) Cussotto, Sofia Publication date 2019 Original citation Cussotto, S. 2019. Effects of psychotropic drugs on the microbiota-gut- liver-brain axis. PhD Thesis, University College Cork. Type of publication Doctoral thesis Rights © 2019, Sofia Cussotto. http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/ Item downloaded http://hdl.handle.net/10468/9468 from Downloaded on 2021-09-23T15:30:09Z Ollscoil na hÉireann, Corcaigh National University of Ireland, Cork Department of Anatomy and Neuroscience Head of Dept. John F. Cryan Effects of Psychotropic Drugs on the Microbiota-Gut-Liver-Brain Axis Thesis presented by Sofia Cussotto, MPharm Under the supervision of Prof. John F. Cryan Prof. Timothy G. Dinan For the degree of Doctor of Philosophy June 2019 Table of Contents Declaration ......................................................................................................... IV Author Contributions .......................................................................................... IV Acknowledgments ............................................................................................... V Publications and presentations ........................................................................... VI Abstract ............................................................................................................ VIII -

Advances in PCR Based Detection of Mycoplasmas Contaminating Cell Cultures

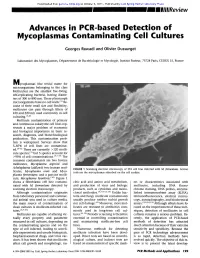

Downloaded from genome.cshlp.org on October 6, 2021 - Published by Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press Advances in PCR based Detection of Mycoplasmas Contaminating Cell Cultures Georges Rawadi and Olivier Dussurget Laboratoire des Mycoplasmes, D~partement de Bact&iologie et Mycologie, Institut Pasteur, 75724 Paris, CEDEX 15, France M ycoplasmas (the trivial name for microorganisms belonging to the class Mollicutes) are the smallest free-living, self-replicating bacteria, having diame- ters of 300 to 800 nm. These pleomorph microorganisms have no cell walls. (1~ Be- cause of their small size and flexibility, mollicutes can pass through filters of 450 and 220 nm used commonly in cell culturing. ~,2) Mollicute contamination of primary and continuous eukaryotic cell lines rep- resents a major problem of economic and biological importance in basic re- search, diagnosis, and biotechnological production. This contamination prob- lem is widespread. Surveys show that 5-87% of cell lines are contaminat- ed. (3-6~ There are currently ~120 molli- cute species, (~ but 5 species account for ~>95% of cell contaminations. (3'7-9~ The common contaminants are two bovine mollicutes, Mycoplasma arginini and Acholeplasma laidlawii; two human mol- FIGURE 1 Scanning electron microscopy of 3T6 cell line infected with M. fermentans. Arrows licutes, Mycoplasma orale and Myco- indicate the mycoplasmas adsorbed on the cell surface. plasma fermentans; and a porcine molli- cute, Mycoplasma hyorhinis. (1~ Figure 1 shows a fibroblastic cell line contami- cleic acid and amino acid metabolism, ers or characteristics associated with nated with M. fermentans detected by and production of virus and biologic mollicutes, including DNA fluoro- scanning electron microscopy. -

Microbiome Species Average Counts (Normalized) Veillonella Parvula

Table S2. Bacteria and virus detected with RN OLP Microbiome Species Average Counts (normalized) Veillonella parvula 3435527.229 Rothia mucilaginosa 1810713.571 Haemophilus parainfluenzae 844236.8342 Fusobacterium nucleatum 825289.7789 Neisseria meningitidis 626843.5897 Achromobacter xylosoxidans 415495.0883 Atopobium parvulum 205918.2297 Campylobacter concisus 159293.9124 Leptotrichia buccalis 123966.9359 Megasphaera elsdenii 87368.48455 Prevotella melaninogenica 82285.23784 Selenomonas sputigena 77508.6755 Haemophilus influenzae 76896.39289 Porphyromonas gingivalis 75766.09645 Rothia dentocariosa 64620.85367 Candidatus Saccharimonas aalborgensis 61728.68147 Aggregatibacter aphrophilus 54899.61834 Prevotella intermedia 37434.48581 Tannerella forsythia 36640.47285 Streptococcus parasanguinis 34865.49274 Selenomonas ruminantium 32825.83925 Streptococcus pneumoniae 23422.9219 Pseudogulbenkiania sp. NH8B 23371.8297 Neisseria lactamica 21815.23198 Streptococcus constellatus 20678.39506 Streptococcus pyogenes 20154.71044 Dichelobacter nodosus 19653.086 Prevotella sp. oral taxon 299 19244.10773 Capnocytophaga ochracea 18866.69759 [Eubacterium] eligens 17926.74096 Streptococcus mitis 17758.73348 Campylobacter curvus 17565.59393 Taylorella equigenitalis 15652.75392 Candidatus Saccharibacteria bacterium RAAC3_TM7_1 15478.8893 Streptococcus oligofermentans 15445.0097 Ruminiclostridium thermocellum 15128.26924 Kocuria rhizophila 14534.55059 [Clostridium] saccharolyticum 13834.76647 Mobiluncus curtisii 12226.83711 Porphyromonas asaccharolytica 11934.89197