Never Let You Go Titled

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Songs by Artist

Reil Entertainment Songs by Artist Karaoke by Artist Title Title &, Caitlin Will 12 Gauge Address In The Stars Dunkie Butt 10 Cc 12 Stones Donna We Are One Dreadlock Holiday 19 Somethin' Im Mandy Fly Me Mark Wills I'm Not In Love 1910 Fruitgum Co Rubber Bullets 1, 2, 3 Redlight Things We Do For Love Simon Says Wall Street Shuffle 1910 Fruitgum Co. 10 Years 1,2,3 Redlight Through The Iris Simon Says Wasteland 1975 10, 000 Maniacs Chocolate These Are The Days City 10,000 Maniacs Love Me Because Of The Night Sex... Because The Night Sex.... More Than This Sound These Are The Days The Sound Trouble Me UGH! 10,000 Maniacs Wvocal 1975, The Because The Night Chocolate 100 Proof Aged In Soul Sex Somebody's Been Sleeping The City 10Cc 1Barenaked Ladies Dreadlock Holiday Be My Yoko Ono I'm Not In Love Brian Wilson (2000 Version) We Do For Love Call And Answer 11) Enid OS Get In Line (Duet Version) 112 Get In Line (Solo Version) Come See Me It's All Been Done Cupid Jane Dance With Me Never Is Enough It's Over Now Old Apartment, The Only You One Week Peaches & Cream Shoe Box Peaches And Cream Straw Hat U Already Know What A Good Boy Song List Generator® Printed 11/21/2017 Page 1 of 486 Licensed to Greg Reil Reil Entertainment Songs by Artist Karaoke by Artist Title Title 1Barenaked Ladies 20 Fingers When I Fall Short Dick Man 1Beatles, The 2AM Club Come Together Not Your Boyfriend Day Tripper 2Pac Good Day Sunshine California Love (Original Version) Help! 3 Degrees I Saw Her Standing There When Will I See You Again Love Me Do Woman In Love Nowhere Man 3 Dog Night P.S. -

Additional Karaoke Listings Updated February 2021! 1

Artist Song Title 1975 Chocolate 1975, The Sincerity is Scary 5 Seconds of Summer Want you back 5 Seconds of Summer Easier ACDC Big Balls Adele All I Ask Adele Cold Shoulder Adele Melt My Heart to Stone Adele Million Years Ago Adele Sweetest Devotion Adele Hello Adele I Can't Make You Love Me Adele Love in The Dark Adele One and Only Adele Send My Love to Your New Lover Adele Take It All Adele When We Were Young Adele Remedy Adele Love Song Afroman Colt 45 AJR Burn the House Down Alabama Angels Among us Alabama Forty Hour Week Alabama Roll on Eighteen Wheeler Alabama Lady down on love Alaina, Lauren Road Less Traveled Alaina, Lauren Wings of an Angel Alaina, Lauren Ladies in the 90s Alaina, Lauren Getting Good Alaina, Lauren Other Side, The Aldean, Jason Tattoos on this town ADDITIONAL KARAOKE LISTINGS UPDATED FEBRUARY 2021! 1 Aldean, Jason Just Getting Started Aldean, Jason Lights Come On Aldean, Jason Little More Summertime, A Aldean, Jason This Plane Don't Go There Aldean, Jason Tonight Looks Good On You Aldean, Jason Gettin Warmed up Aldean, Jason Truth, The Aldean, Jason You make it easy Aldean, Jason Girl Like you Aldean, Jason Camouflage Hat Aldean, Jason We Back Aldean, Jason Rearview Town Aldean, Jason & Miranda Lambert Drowns The Whiskey Alice in Chains Man In The Box Alice in Chains No Excuses Alice in Chains Your Decision Alice in Chains Nutshell Alice in Chains Rooster Allan, Gary Every Storm (Runs Out of Rain) Allan, Gary Runaway Allen, Jimmie Best shot Anderson, John Swingin' Andress, Ingrid Lady Like Andress, Ingrid More Hearts Than Mine Angels and Airwaves Kiss & Tell Angston, Jon When it comes to loving you Animals, The Bring It On Home To Me Arctic Monkeys Do I Wanna Know Ariana Grande Breathin Arthur, James Say You Won't Let Go Arthur, James Naked Arthur, James Empty Space ADDITIONAL KARAOKE LISTINGS UPDATED FEBRUARY 2021! 2 Arthur, James Falling like the stars Arthur, James & Anne Marie Rewrite the Stars Arthur, James & Anne Marie Rewrite The Stars Ashanti Happy Ashanti Helpless (ft. -

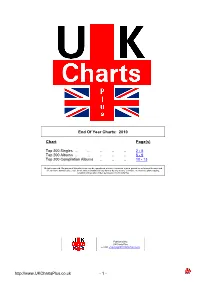

End of Year Charts: 2010

End Of Year Charts: 2010 Chart Page(s) Top 200 Singles .. .. .. .. .. 2 - 5 Top 200 Albums .. .. .. .. .. 6 - 9 Top 200 Compilation Albums .. .. .. 10 - 13 All rights reserved. No portion of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, posted on an Internet/Intranet web site or forum, forwarded by email, or otherwise transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording without prior written permission of UKChartsPlus Published by: UKChartsPlus e-mail: [email protected] http://www.UKChartsPlus.co.uk - 1 - Symbols: Platinum (600,000) Gold (400,000) Silver (200,000) 12” Vinyl only 2010 7” Vinyl only Download only Entry Date 2010 2009 2008 2007 Title - Artist Label (Cat. No.) (w/e) High Wks 1 -- -- -- LOVE THE WAY YOU LIE - Eminem featuring Rihanna Interscope (2748233) 03/07/2010 2 28 2 -- -- -- WHEN WE COLLIDE - Matt Cardle Syco (88697837092) 25/12/2010 13 3 3 -- -- -- JUST THE WAY YOU ARE (AMAZING) - Bruno Mars Elektra ( USAT21001269) 02/10/2010 12 15 4 -- -- -- ONLY GIRL (IN THE WORLD) - Rihanna Def Jam (2755511) 06/11/2010 12 10 5 -- -- -- OMG - Usher featuring will.i.am LaFace ( USLF20900103) 03/04/2010 1 41 6 -- -- -- FIREFLIES - Owl City Island ( USUM70916628) 16/01/2010 13 51 7 -- -- -- AIRPLANES - B.o.B featuring Hayley Williams Atlantic (AT0353CD) 12/06/2010 1 31 8 -- -- -- CALIFORNIA GURLS - Katy Perry featuring Snoop Dogg Virgin (VSCDT2013) 03/07/2010 12 28 WE NO SPEAK AMERICANO - Yolanda Be Cool vs D Cup 9 -- -- -- 17/07/2010 1 26 All Around The World/Universal -

Read the I Wish I Was a Mountain Book

On the day of the famous annual fair, the town of Faldum receives an unexpected visit. A wanderer offers to grant a wish to anyone who wants one. Before long, the city is transformed. Mansions stand where mud huts once squatted, and beggars ride around in horse drawn carriages. And one man wishes to be turned into a mountain. Written by former Glastonbury Poetry Slam Champion Toby Thompson, I Wish I Was A Mountain uses rhyme, rhythm, and just a smattering of metaphysical philosophy to boldly reimagine Hermann Hesse’s classic fairytale. Do we really need the things that we long for? What do mountains feel? How did time begin? Ideal for reading aloud and sharing with children and family, this soul-enhancing book is the perfect read, whose words will stay with you for a lifetime. Experience a little bit of magic on every page, straight from the stage at the egg Theatre. This is a fairytale that doesn’t so much end happily ever after as ask us how the “ever after” affects our daily lives…a short but profound show… which reveals Thompson as a star in the making. ★ ★ ★ ★ Chris Wiegland, The Guardian I Wish I Was A Mountain is a show that combines simplicity and profundity in so appealing a manner that it simply should not be missed. Christopher Hoile, Stage Door He shares this world so generously that it will be yours as soon as you hear it. Gill Kirk, B 24/7 Text © Toby Thompson 2018 Cover Art and Design by B. Mure Toby Thompson has asserted his right under the Copyright, Design and Patents Act 1988, to be identified as the author of this work. -

FROM HERE to HIROSHIMA by Sunniva Lye Axelsen

1 FROM HERE TO HIROSHIMA by Sunniva Lye Axelsen Published by Tiden Norsk Forlag, 2019 An English Sample Translation Translated from the Norwegian by David M. Smith Foreign Rights Gyldendal Agency P.O. Box 6860 St. Olavs plass NO-0130 Oslo Tel: +47 957 81 640 [email protected] http://eng.gyldendal.no Pages 9-23: We get to know Ingrid and her job When the social educator caught fire, I was at home brushing my teeth. I mashed the brush hard against the gums so as to get rid of the rib residue and regretted having accepted the invite. I’d taken off the white blouse and kicked off the black trainers. I was about to leave the blouse on the floor, but since that simply isn’t done, I picked it up and put it in the dirty clothes bin. I kept on regretting, the edges of my mouth specked with white foam. I pressed my nails into my left palm. No matter how hard I brushed, the smell wouldn’t go away, lingering between me and the mirror like the smoke from a grill, a cloud of pork rinds and gløgg and fire as the scorching hot water cascaded down the drain. As usual, the health and welfare office had pulled out all the stops. Every Christmas, they book the local pub by the roundabout, set out torches in the car park, and give each of us rib, lukewarm pork patties, pickles, two glasses of red wine and a thimbleful of aquavit. If we want 2 more drinks, we have to buy them ourselves, even though I’ve often observed the admin team surreptitiously using vouchers. -

From the Outside in the Secret to Automatic Language Growth

From the Outside In The Secret to Automatic Language Growth J. Marvin Brown Copyright 2003, ALG World Co., Ltd. 4 Preface I’ve been trying to learn languages and teach them all my life. I spent the war trying to learn Chinese, and I spent the next 50 years trying to learn 20 more languages and trying to teach two. All this time I was aware, of course, that the only language I really learned was the one I didn’t try to learn. In an educational system where trying is king, how could we ever hope to find out that trying was the villain? It took me a lifetime to see this, and the purpose of this book is to tell you about that lifetime. There are three great scholars, especially, who contributed to my ideas. Their books will help to show where I’m coming from, and their bibliographies will serve to connect my thinking to the relevant literature. William T. Powers. Behavior: The Control of Perception (1973), Aldine Publishing Company. Living Control Systems (1989) and Living Control Systems II (1992). The Control Systems Group, Inc., Gravel Switch, Kentucky. Stephen D. Krashen. The Input Hypothesis (1985). Longman, New York. Gary Cziko. The Things We Do (2000). The MIT Press, Cambridge, Mass. Cascades – The Secret to Automatic Language Growth 5 Contents Introduction page 6 1. Growing Up: Age 3-20 page 8 2. The Three Veils: Age 3-20 page 11 3. The Professional Student: Age 20-37 page 16 4. The Linguist: Age 37-55 page 22 5. -

Karaoke Mietsystem Songlist

Karaoke Mietsystem Songlist Ein Karaokesystem der Firma Showtronic Solutions AG in Zusammenarbeit mit Karafun. Karaoke-Katalog Update vom: 13/10/2020 Singen Sie online auf www.karafun.de Gesamter Katalog TOP 50 Shallow - A Star is Born Take Me Home, Country Roads - John Denver Skandal im Sperrbezirk - Spider Murphy Gang Griechischer Wein - Udo Jürgens Verdammt, Ich Lieb' Dich - Matthias Reim Dancing Queen - ABBA Dance Monkey - Tones and I Breaking Free - High School Musical In The Ghetto - Elvis Presley Angels - Robbie Williams Hulapalu - Andreas Gabalier Someone Like You - Adele 99 Luftballons - Nena Tage wie diese - Die Toten Hosen Ring of Fire - Johnny Cash Lemon Tree - Fool's Garden Ohne Dich (schlaf' ich heut' nacht nicht ein) - You Are the Reason - Calum Scott Perfect - Ed Sheeran Münchener Freiheit Stand by Me - Ben E. King Im Wagen Vor Mir - Henry Valentino And Uschi Let It Go - Idina Menzel Can You Feel The Love Tonight - The Lion King Atemlos durch die Nacht - Helene Fischer Roller - Apache 207 Someone You Loved - Lewis Capaldi I Want It That Way - Backstreet Boys Über Sieben Brücken Musst Du Gehn - Peter Maffay Summer Of '69 - Bryan Adams Cordula grün - Die Draufgänger Tequila - The Champs ...Baby One More Time - Britney Spears All of Me - John Legend Barbie Girl - Aqua Chasing Cars - Snow Patrol My Way - Frank Sinatra Hallelujah - Alexandra Burke Aber Bitte Mit Sahne - Udo Jürgens Bohemian Rhapsody - Queen Wannabe - Spice Girls Schrei nach Liebe - Die Ärzte Can't Help Falling In Love - Elvis Presley Country Roads - Hermes House Band Westerland - Die Ärzte Warum hast du nicht nein gesagt - Roland Kaiser Ich war noch niemals in New York - Ich War Noch Marmor, Stein Und Eisen Bricht - Drafi Deutscher Zombie - The Cranberries Niemals In New York Ich wollte nie erwachsen sein (Nessajas Lied) - Don't Stop Believing - Journey EXPLICIT Kann Texte enthalten, die nicht für Kinder und Jugendliche geeignet sind. -

OZ Nashville Oasis Center

28 April 2018 OZ Nashville to benefit Oasis Center Event Chairs Lechelle Moore | Holly Merrell Kelly Mitchell | Lieann O'Brien The Producer The Director $20,000 $15,000 "Presenting" Sponsor Only in Nashville presented by [your company's name] Two Premier tables with seating for up to 20! Logo placement on all event materials and Your guests will enjoy complimentary bar advertisement including exclusive service, dinner, and valet parking! sponsorship on website home page banner Build-A-Bike corporate team activity Three Premier tables with seating for up to 30! Your guests will enjoy complimentary bar Full page color ad inside front cover or inside service, dinner, and valet parking. back cover of event program Build-A-Bike corporate team activity Opportunity to open event with an onstage Premium logo placement in: welcome Print advertisement (NFocus) Live event media Exclusive full page color ad on back cover of Invitations* event program Agency website up until 30 days after the event Premium logo placement in: Social media Print advertisement (NFocus) Live event media Invitations* Agency website up until 30 days after the event Social media Jimmy Robbins - OIN Alum 2014 lori mckenna - OIN Alum 2015 "Sure Be Cool If You Did" Blake Shelton "Humble and Kind" Tim McGraw "Beachin'" Jake Owen "Girl Crush" Little Big Town "We Were Us" Keith Urban & Miranda Lambert "I Want Crazy" Hunter Hayes The Manager The Engineer $10,000 $5,000 One Premier table with seating for 12 guests! One Premier table with seating for 10 guests! Your guests will enjoy -

Molly Lovette - Song List

Molly Lovette - Song List My Church (Maren Morris) Wagon Wheel (Darius Rucker) {C4 G D Em C} Wide Open Spaces (Dixie Chicks) She’s in Love with the Boy (Trisha Yearwood) Whiskey Glasses (Morgan Wallen) Me and Bobby McGee (Janis Joplin) I Wanna Dance with Somebody (Whitney Houston) Delta Dawn (Tanya Tucker) Sweet Child o’ Mine (Guns n’ Roses) Linger (The Cranberries) Crush (Molly Lovette) Before He Cheats (Carrie Underwood) White Liar (Miranda Lambert) Jolene (Dolly Parton) Come Over (Kenny Chesney) Babe (Sugarland) Lovin’ You (Molly Lovette) Tequila (Dan + Shay) I Wish Grandpas Never Died (Riley Green) Baby Girl (Sugarland) You Belong With Me (Taylor Swift) Gunpowder & Lead (Miranda Lambert) Desperate Man (Eric Church) Girl (Maren Morris) Zombie (The Cranberries) Any Man of Mine (Shania Twain) People Are Crazy (Billy Currington) Who Knew (Pink) Travelin’ Soldier (Dixie Chicks) Bohemian Rhapsody (Queen) Bad For You (Molly Lovette) Just to see you Smile (Tim McGraw) Follow Your Arrow (Kacey Musgraves) Strawberry Wine (Deana Carter) Love Story (Taylor Swift) 9 to 5 (Dolly Parton) Believe (Cher) Landslide (Fleetwood Mac) Fastest Girl in Town (Miranda Lambert) Little White Church (Little Big Town) Rich (Maren Morris) Wanted Dead or Alive (Bon Jovi) Folsom Prison Blues (Johnny Cash) Rainbow (Kacey Musgraves) Church Bells (Carrie Underwood) Girl Crush (Little Big Town) Old Time Rock and Roll (Bob Seger) The Dance (Garth Brooks) Pink Houses (John -

Songs by Title

16,341 (11-2020) (Title-Artist) Songs by Title 16,341 (11-2020) (Title-Artist) Title Artist Title Artist (I Wanna Be) Your Adams, Bryan (Medley) Little Ole Cuddy, Shawn Underwear Wine Drinker Me & (Medley) 70's Estefan, Gloria Welcome Home & 'Moment' (Part 3) Walk Right Back (Medley) Abba 2017 De Toppers, The (Medley) Maggie May Stewart, Rod (Medley) Are You Jackson, Alan & Hot Legs & Da Ya Washed In The Blood Think I'm Sexy & I'll Fly Away (Medley) Pure Love De Toppers, The (Medley) Beatles Darin, Bobby (Medley) Queen (Part De Toppers, The (Live Remix) 2) (Medley) Bohemian Queen (Medley) Rhythm Is Estefan, Gloria & Rhapsody & Killer Gonna Get You & 1- Miami Sound Queen & The March 2-3 Machine Of The Black Queen (Medley) Rick Astley De Toppers, The (Live) (Medley) Secrets Mud (Medley) Burning Survivor That You Keep & Cat Heart & Eye Of The Crept In & Tiger Feet Tiger (Down 3 (Medley) Stand By Wynette, Tammy Semitones) Your Man & D-I-V-O- (Medley) Charley English, Michael R-C-E Pride (Medley) Stars Stars On 45 (Medley) Elton John De Toppers, The Sisters (Andrews (Medley) Full Monty (Duets) Williams, Sisters) Robbie & Tom Jones (Medley) Tainted Pussycat Dolls (Medley) Generation Dalida Love + Where Did 78 (French) Our Love Go (Medley) George De Toppers, The (Medley) Teddy Bear Richard, Cliff Michael, Wham (Live) & Too Much (Medley) Give Me Benson, George (Medley) Trini Lopez De Toppers, The The Night & Never (Live) Give Up On A Good (Medley) We Love De Toppers, The Thing The 90 S (Medley) Gold & Only Spandau Ballet (Medley) Y.M.C.A. -

Music, Dementia, and the Reality of Being Yourself Kayleen M

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2014 Music, Dementia, and the Reality of Being Yourself Kayleen M. Justus Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF MUSIC MUSIC, DEMENTIA, AND THE REALITY OF BEING YOURSELF By KAYLEEN M. JUSTUS A Dissertation submitted to the College of Music in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Degree Awarded: Spring Semester, 2014 Kayleen M. Justus defended this dissertation on on April 28th, 2014. The members of the supervisory committee were: Frank Gunderson Professor Directing Dissertation Alice-Ann Darrow University Representative Michael B. Bakan Committee Member Charles E. Brewer Committee Member The Graduate School has verified and approved the above-named committee members, and certifies that the dissertation has been approved in accordance with university requirements. ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to thank the clients, administrators, staff, and fellow volunteers at the Alzheimer’s Project Tallahassee, Inc., who demonstrate beautifully, and in so many profound ways, what Selflessness actually means. I feel fortunate to have spent so many Fridays singing, playing bingo, sharing memories, laughing, and working together. I would also like to thank my advisor, Frank Gunderson, who has supported my inclination to think differently by preferring not to counter my intuition and curiosity as a scholar. By mentoring me via a “politics of subtraction” in this way, he effectively opened up a space in which I could imagine and construct this project. I am also grateful to the members of my committee, Michael Bakan, Charles Brewer, and Alice-Ann Darrow, for their input and support in this project. -

Shared Stories

Shared Stories Shared by Morgan, 19 I was bullied in elementary school because I was short and different. Kids would spread rumors about me, tease me, and call me names. I told the teachers what was going on but nothing was being done and the bullying got worse. I started to come home from school crying and sometimes I would even be crying when my parents dropped me off at school. So I told my parents what was going on and they did something about it and things got better. No one deserves to be bullied. After experiencing being bullied I am taking a stand against bullying. I am on a mission to stop bullying. Shared by Tan, 20 When I was in high school, I was a very quiet and shy girl. I was afraid of people getting too close to me, as a consequence I did not have any friends I thought I was mysterious in that way. It started with a boy who seated beside me. One day, when I was paying close attention to the teacher I realised that he could not keep his eyes off me. I admit I was delighted because I never had a guy mesmerised by my beauty before and I took it as a big compliment. Besides, I thought he was quite cute! As usual, the classroom teases typical of high school started. Everyone said that this guy had a big crush on a girl in our class, my heart stopped in my chest: I was waiting for him to say my name and admit.