Lyjournal II, No

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

10U/111121 (To Bejilled up by the Candidate by Blue/Black Ball-Point Pen)

Question Booklet No. 10U/111121 (To bejilled up by the candidate by blue/black ball-point pen) Roll No. LI_..L._.L..._L.-..JL--'_....l._....L_.J Roll No. (Write the digits in words) ............................................................................................... .. Serial No. of Answer Sheet .............................................. D~'y and Date ................................................................... ( Signature of Invigilator) INSTRUCTIONS TO CANDIDATES (Use only bluelblack ball-point pen in the space above and on both sides of the Answer Sheet) 1. Within 10 minutes of the issue of the Question Booklet, check the Question Booklet to ensure that it contains all the pages in correct sequence and that no page/question is missing. In case of faulty Question Booklet bring it to the notice oflhe Superintendentllnvigilators immediately to obtain a fresh Question Booklet. 2. Do not bring any loose paper, written or blank, inside the Examination Hall except the Admit Card without its envelope, .\. A separate Answer Sheet b,' given. It !J'hould not he folded or mutilated A second Answer Sheet shall not be provided. Only the Answer Sheet will be evaluated 4. Write your Roll Number and Serial Number oflhe Answer Sheet by pen in the space prvided above. 5. On the front page ofthe Answer Sheet, write hy pen your Roll Numher in the space provided at the top and hy darkening the circles at the bottom. AI!J'o, wherever applicahle, write the Question Booklet Numher and the Set Numher in appropriate places. 6. No overwriting is allowed in the entries of Roll No., Question Booklet no. and Set no. (if any) on OMR sheet and Roll No. -

Bharata Natyam Is a Traditional Female Solo Dance Form in Tamil Nadu, Southeast India

=Wor d of Dance< Asian Dance SECOND EDITION WoD-Asian dummy.indd 1 12/11/09 3:16:42 PM World of Dance African Dance, Second Edition Asian Dance, Second Edition Ballet, Second Edition European Dance: Ireland, Poland, Spain, and Greece, Second Edition Latin and Caribbean Dance Middle Eastern Dance, Second Edition Modern Dance, Second Edition Popular Dance: From Ballroom to Hip-Hop WoD-Asian dummy.indd 2 12/11/09 3:16:43 PM =Wor d of Dance< Asian Dance SECOND EDITION Janet W. Descutner Consulting editor: Elizabeth A. Hanley, Associate Professor Emerita of Kinesiology, Penn State University Foreword by Jacques D’Amboise, Founder of the National Dance Institute WoD-Asian dummy.indd 3 12/11/09 3:16:44 PM World of Dance: Asian Dance, Second Edition Copyright © 2010 by Infobase Publishing All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage or retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher. For information, contact: Chelsea House An imprint of Infobase Publishing 132 West 31st Street New York NY 10001 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Descutner, Janet. Asian dance / by Janet W. Descutner. — 2nd ed. p. cm. — (World of dance) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-1-60413-478-0 (hardcover) ISBN 978-1-4381-3078-1 (e-book) 1. Dance—Asia. I. Title. II. Series. GV1689.D47 2010 793.3195—dc22 2009019582 Chelsea House books are available at special discounts when purchased in bulk quantities for businesses, associations, institutions, or sales promotions. -

Pune Dance Season 2019 Pune Dance Season 2019

Magazine for the classical dance community Pune Dance Season 2019 Pune Dance Season 2019 Shastriya Nrutya Sanvardhan Sanstha (SNSS) is an organization of the dancers, for the dancers, by the dancers. Sucheta Chapekar, Shama Bhate and Maneesha Sathe are the founder members of this organization which was started in Pune last year. The organization aims at creating a platform for the young talent of the city and promoting the Pune dancers on a global level. SNSS has already successfully conducted performance avenues and opportunities in the short span of its formation. The organization spreading its wings fast, hosted the first ever Dance Season in Pune from 20th to 30th April 2019, to celebrate the International Dance day. These 10 days saw Pune dancers from 7 to 40 yrs dive in the activities organized by different dancers under the auspicies of SNSS. It was a full spectrum with performances, competitions, art exhibitions, elocution, essay writing, workshops, interaction sessions which led to the grand finale on 30th where more than 25 groups performed ending the season with a bang! Giving you all a gist of all the events… # Workshop focusing on Psychological Aspect & Personality Development through dance. As per renowned Marathi writer, Pu La Deshpande, education can help an individual bring in money which is required for survival. However, it is only due to one’s connection with some or the other form of art that makes one’s life livable. Focusing and enlightening on this topic a workshop was organized by Manasi which focused on the psychology of students and their parents. -

SANGEET MELA 2015 2Nd Annual Indian Classical Music & Dance Festival Saturday 19Th September Queensland Multicultural Centre Brisbane, Australia Programme

SANGEET MELA 2015 2nd Annual Indian Classical Music & Dance Festival Saturday 19th September Queensland Multicultural Centre Brisbane, Australia Programme Afternoon Session: 2pm to 4:30pm 1. SANGEET PREMI RISING STAR AWARD WINNERS: a) BHARAT NATYAM DANCE – Ku Mathuja Bavanendrakumar b) TABLA SOLO – Sri Sanjey Sivaananthan c) VOCAL (Hindustani) – Sri Manbir Singh (Sydney) d) VOCAL (Carnatic) and MRIDANGAM – Ku Roshini Sriram and Sri Arthavan Selvanathan 2. SITAR – Dr Indranil Chatterjee ~ Interval ~ Sunset Session: 4:50pm to 7pm 1. BHARAT NATYAM DANCE – Ku Janani Ganapathi (Switzerland) 2. TABLA SOLO – Pt Pooran Maharaj (Varanasi) 3. FLUTE (Carnatic) – Sri Sridhar Chari (Melbourne) 4. VOCAL (Hindustani) – Dr Mansey Kinarivala ~ Interval ~ Late Session: 7:45pm to 10:30pm 1. KATHAK DANCE – Dr Helena Joshi with live ensemble 2. VOCAL (Hindustani) – Kumar Gaurav Kohli (Jalandhar) 3. VOCAL (Carnatic) – Smt Manda Sudharani (Vizag) Please enjoy delicious refreshments in the lobby, supplied by Sitar Restaurant. No food to be brought into the auditorium. Please be seated in timely fashion and be considerate of fellow listeners. Due to the extent of the programme we must run on time. Please enter and leave the auditorium between items. From the Festival Organisers Festival Director Shen Flindell (EthnoSuperLounge) The oral tradition of Indian classical music (guru-shishya parampara) connects us directly back through the ages to the timeless wisdom of the Vedas, which tell us that music is the most direct path to “God”. I really believe that no matter what your religion nor which part of India or the world you come from, Indian classical music is something we can all be really proud of. -

Annual Report 1990 .. 91

SANGEET NAT~AKADEMI . ANNUAL REPORT 1990 ..91 Emblem; Akademi A wards 1990. Contents Appendices INTRODUCTION 0 2 Appendix I : MEMORANDUM OF ASSOCIATION (EXCERPTS) 0 53 ORGANIZATIONAL SET-UP 05 AKADEMI FELLOWSHIPS/ AWARDS Appendix II : CALENDAR OF 19900 6 EVENTS 0 54 Appendix III : GENERAL COUNCIL, FESTIVALS 0 10 EXECUTIVE BOARD, AND THE ASSISTANCE TO YOUNG THEATRE COMMITTEES OF THE WORKERS 0 28 AKADEMID 55 PROMOTION AND PRESERVATION Appendix IV: NEW AUDIO/ VIDEO OF RARE FORMS OF TRADITIONAL RECORDINGS 0 57 PERFORMING ARTS 0 32 Appendix V : BOOKS IN PRINT 0 63 CULTURAL EXCHANGE Appendix VI : GRANTS TO PROGRAMMES 0 33 INSTITUTIONS 1990-91 064 PUBLICATIONS 0 37 Appendix VII: DISCRETIONARY DOCUMENTATION / GRANTS 1990-91 071 DISSEMINATION 0 38 Appendix VIll : CONSOLIDATED MUSEUM OF MUSICAL BALANCE SHEET 1990-91 0 72 INSTRUMENTS 0 39 Appendix IX : CONSOLIDATED FINANCIAL ASSISTANCE TO SCHEDULE OF FIXED CULTURAL INSTITUTIONS 0 41 ASSETS 1990-91 0 74 LIBRARY AND LISTENING Appendix X : PROVIDENT FUND ROOMD41 BALANCE SHEET 1990-91 078 BUDGET AND ACCOUNTS 0 41 Appendix Xl : CONSOLIDATED INCOME & EXPENDITURE IN MEMORIAM 0 42 ACCOUNT 1990-91 KA THAK KENDRA: DELHI 0 44 (NON-PLAN & PLAN) 0 80 JA WAHARLAL NEHRU MANIPUR Appendix XII : CONSOLIDATED DANCE ACADEMY: IMPHAL 0 50 INCOME & EXPENDITURE ACCOUNT 1990-91 (NON-PLAN) 0 86 Appendix Xlll : CONSOLIDATED INCOME & EXPENDITURE ACCOUNT 1990-91 (PLAN) 0 88 Appendix XIV : CONSOLIDATED RECEIPTS & PAYMENTS ACCOUNT 1990-91 (NON-PLAN & PLAN) 0 94 Appendix XV : CONSOLIDATED RECEIPTS & PAYMENTS ACCOUNT 1990-91 (NON-PLAN) 0 104 Appendix XVI : CONSOLIDATED RECEIPTS & PAYMENTS ACCOUNT 1990-91 (PLAN) 0 110 Introduction Apart from the ongoing schemes and programmes, the Sangeet Natak Akademi-the period was marked by two major National Academy of Music, international festivals presented Dance, and Drama-was founded by the Akademi in association in 1953 for the furtherance of with the Indian Council for the performing arts of India, a Cultural Relations. -

Sankeet Natak Akademy Awards from 1952 to 2016

All Sankeet Natak Akademy Awards from 1952 to 2016 Yea Sub Artist Name Field Category r Category Prabhakar Karekar - 201 Music Hindustani Vocal Akademi 6 Awardee Padma Talwalkar - 201 Music Hindustani Vocal Akademi 6 Awardee Koushik Aithal - 201 Music Hindustani Vocal Yuva Puraskar 6 Yashasvi 201 Sirpotkar - Yuva Music Hindustani Vocal 6 Puraskar Arvind Mulgaonkar - 201 Music Hindustani Tabla Akademi 6 Awardee Yashwant 201 Vaishnav - Yuva Music Hindustani Tabla 6 Puraskar Arvind Parikh - 201 Music Hindustani Sitar Akademi Fellow 6 Abir hussain - 201 Music Hindustani Sarod Yuva Puraskar 6 Kala Ramnath - 201 Akademi Music Hindustani Violin 6 Awardee R. Vedavalli - 201 Music Carnatic Vocal Akademi Fellow 6 K. Omanakutty - 201 Akademi Music Carnatic Vocal 6 Awardee Neela Ramgopal - 201 Akademi Music Carnatic Vocal 6 Awardee Srikrishna Mohan & Ram Mohan 201 (Joint Award) Music Carnatic Vocal 6 (Trichur Brothers) - Yuva Puraskar Ashwin Anand - 201 Music Carnatic Veena Yuva Puraskar 6 Mysore M Manjunath - 201 Music Carnatic Violin Akademi 6 Awardee J. Vaidyanathan - 201 Akademi Music Carnatic Mridangam 6 Awardee Sai Giridhar - 201 Akademi Music Carnatic Mridangam 6 Awardee B Shree Sundar 201 Kumar - Yuva Music Carnatic Kanjeera 6 Puraskar Ningthoujam Nata Shyamchand 201 Other Major Music Sankirtana Singh - Akademi 6 Traditions of Music of Manipur Awardee Ahmed Hussain & Mohd. Hussain (Joint Award) 201 Other Major Sugam (Hussain Music 6 Traditions of Music Sangeet Brothers) - Akademi Awardee Ratnamala Prakash - 201 Other Major Sugam Music Akademi -

635301449163371226 IIC ANNUAL REPORT 2013-14 5-3-2014.Pdf

2013-2014 2013 -2014 Annual Report IND I A INTERNAT I ONAL CENTRE 2013-2014 IND I A INTERNAT I ONAL CENTRE New Delhi Board of Trustees Mr. Soli J. Sorabjee, President Justice (Retd.) B.N. Srikrishna Professor M.G.K. Menon Mr. L.K. Joshi Dr. (Smt.) Kapila Vatsyayan Dr. Kavita A. Sharma, Director Mr. N. N. Vohra Executive Members Dr. Kavita A. Sharma, Director Professor Dinesh Singh Mr. K. Raghunath Dr. Biswajit Dhar Dr. (Ms) Sukrita Paul Kumar Cmde.(Retd.) Ravinder Datta, Secretary Cmde.(Retd.) C. Uday Bhaskar Mr. P.R. Sivasubramanian, Hony. Treasurer Mrs. Meera Bhatia Finance Committee Justice (Retd.) B.N. Srikrishna, Dr. Kavita A. Sharma, Director Chairman Mr. P.R. Sivasubramanian, Hony. Treasurer Mr. M. Damodaran Cmde. (Retd.) Ravinder Datta, Secretary Cmde.(Retd.) C. Uday Bhaskar Mr. Ashok K. Chopra, Chief Finance Officer Medical Consultants Dr. K.P. Mathur Dr. Rita Mohan Dr. K.A. Ramachandran Dr. Gita Prakash Dr. Mohammad Qasim IIC Senior Staff Ms Omita Goyal, Chief Editor Mr. A.L. Rawal, Dy. General Manager Dr. S. Majumdar, Chief Librarian Mr. Vijay Kumar, Executive Chef Ms Premola Ghose, Chief, Programme Division Mr. Inder Butalia, Sr. Finance and Accounts Officer Mr. Arun Potdar, Chief, Maintenance Division Ms Hema Gusain, Purchase Officer Mr. Amod K. Dalela, Administration Officer Ms Seema Kohli, Membership Officer Annual Report 2013-2014 It is a privilege to present the 53rd Annual Report of the India International Centre for the period 1 February 2013 to 31 January 2014. The Board of Trustees reconstituted the Finance Committee for the two-year period April 2013 to March 2015 with Justice B.N. -

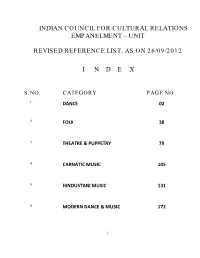

Unit Revised Reference List, As on 26/09/2012 I

INDIAN COUNCIL FOR CULTURAL RELATIONS EMPANELMENT – UNIT REVISED REFERENCE LIST, AS ON 26/09/2012 I N D E X S.NO. CATEGORY PAGE NO 1. DANCE 02 2. FOLK 38 3. THEATRE & PUPPETRY 79 4. CARNATIC MUSIC 105 5. HINDUSTANI MUSIC 131 6. MODERN DANCE & MUSIC 172 1 INDIAN COUNCIL FOR CULTURAL RELATIONS EMPANELMEMT SECTION REVISED REFERENCE LIST FOR DANCE - AS ON 26/09/2012 S.NO. CATEGORY PAGE NO 1. BHARATANATYAM 3 – 11 2. CHHAU 12 – 13 3. KATHAK 14 – 19 4. KATHAKALI 20 – 21 5. KRISHNANATTAM 22 6. KUCHIPUDI 23 – 25 7. KUDIYATTAM 26 8. MANIPURI 27 – 28 9. MOHINIATTAM 29 – 30 10. ODISSI 31 – 35 11. SATTRIYA 36 12. YAKSHAGANA 37 2 REVISED REFERENCE LIST FOR DANCE AS ON 26/09/2012 BHARATANATYAM OUTSTANDING 1. Ananda Shankar Jayant (Also Kuchipudi) (Up) 2007 2. Bali Vyjayantimala 3. Bhide Sucheta 4. Chandershekar C.V. 03.05.1998 5. Chandran Geeta (NCR) 28.10.1994 (Up) August 2005 6. Devi Rita 7. Dhananjayan V.P. & Shanta 8. Eshwar Jayalakshmi (Up) 28.10.1994 9. Govind (Gopalan) Priyadarshini 03.05.1998 10. Kamala (Migrated) 11. Krishnamurthy Yamini 12. Malini Hema 13. Mansingh Sonal (Also Odissi) 14. Narasimhachari & Vasanthalakshmi 03.05.1998 15. Narayanan Kalanidhi 16. Pratibha Prahlad (Approved by D.G March 2004) Bangaluru 17. Raghupathy Sudharani 18. Samson Leela 19. Sarabhai Mallika (Up) 28.10.1994 20. Sarabhai Mrinalini 21. Saroja M K 22. Sarukkai Malavika 23. Sathyanarayanan Urmila (Chennai) 28.10.94 (Up)3.05.1998 24. Sehgal Kiran (Also Odissi) 25. Srinivasan Kanaka 26. Subramanyam Padma 27. -

INSIDE Aekalavya Awardees Lasyakala & Artists Guru Deba Prasad Nrutyadhara & Artists a Vista of Indian Art, Culture

1st Edition of A Vista of Indian Art, Culture and Dance INSIDE Aekalavya Awardees Lasyakala & Artists Guru Deba Prasad Nrutyadhara & Artists Channel Partners Transactions Per Month Employees Developer Clients Happy Customers Monthly Website Visitors Worth of Property Sold India Presence : Ahmedabad | Bengaluru | Chennai | Gurugram| Hyderabad | Jaipur Kolkata | Lucknow | Mumbai | Navi Mumbai | New Delhi | Noida | Pune | Thane | Vishakhapatnam | Vijayawada Global Presence : Abu Dhabi | Bahrain| Doha | Dubai | Hong Kong | Kuwait | Muscat | Melbourne | Sharjah Singapore | Sydney | Toronto WWW.SQUAREYARDS.COM SY Solutions PTE Limited, 1 Raffles Place, Level 19-61, One Raffles Place, Tower 2, Singapore - 048616 Message J P Jaiswal, Chairman & Managing Director, Peakmore International Pte Ltd Past Director, Singapore Indian Chamber of Commerce & Industry (2014-2018) Dear Friends, It gives me immense pleasure to congratulate Guru Deba Prasad Nrutyadhara, Singapore and the organizers for bringing the popular production Aekalavya Season 11. Congratulations to the esteemed team of Lasyakala for co-producing this beautiful act in classical dance form. It’s also a matter of joy that Padmabibhushan Shilpiguru Mr Raghunath Mohapatra shall grace the program as Chief Guest. I also congratulate to all Aekalavya Season-11 Awardees and extend my best wishes to all the performers. My heartfelt best wishes for a successful performance and wish a joyful evening to all audience. Finally, once again, I thank the organizers for all the effort -

'Dqr'+

I ~: e ~n 1 1 E>:>{ (? cut "i ve Boar rJ 2 ") Dece mber 19'53 Annual Er.'DQr'+: of (3 ang e ?t I' a t rJ~ .'\ ', ade< f or t he yea r 1 c 82- 83 1" cop y of th (:" A ~Tll:al R?;,'")rt of :3a ~1g e ':' t N.s t :-iV -D. )~a d2m L for the yea r 195 2 - 8 3 ;. 3 0 L:~ ',c:>ri L(Jr consic: ' '( :l+: :' , ,' an~ a p pr ov a l of the Executive Boa rd. ·T."" \ A N 1 : U ..r'l 1 T:: n f 'l R J:J p \.) R J.. ~ 0 I 0 '4 1" 9 8 2 - .~ U J 'll ~ S A N G E E Tl :rT _4 A K -t1. K D E t":I 1. IT E Vi D E L II I tion y """as set up by Goverrr11e :n; of the prorIlOtion of perfor:-;-, ing arts. 'L':i 8 L's.d ern:i. c _- ~ ~':J . at th e na tional level for the 1J r::Hrc tion cld :cu Ii ., , Indian music; dance and drama; fn:!:' ma:Lntpn8J::o ~ standards of train ing i n the p erio rming ::;.:::..~t3; 1 '-':;::' revivaly pr2servation, documentation anq dis,:;su. 8:" tion of materials relating to various fOLl l' ~- !, :~." __ .'cA./J- .. ing folk and t:rib~:3.1) of music, dCCl.nce and dra!T 8. ?.nd for the recogn i tion and inst i tut iOll 0 f a'l"lards t C'1 on t standing artistes. -

Kathak Workshop, Delhi, March 24 to 26, 7 9 76. 52

Kathak Workshop, Delhi, March 24 to 26, 7 9 76. Kathak artists are known to be great individualists. When the mystic poet Kabir said : "There are no bags of gems, no flocks of swans; lions do not move about in herds, nor do saints in groups", he might as well have included the Kathaks. Each one of them is an island unto himself. They would rather sit back-to-back than face-to-face. There are many · things that divide them, the most important being the almost fanatic commitment to their gharana-s. But in the month of March this year something happened which bodes well for the future of this very attractive classical dance form. Leading Kathak artists and scholars gathered together in Delhi for three days in a spirit of friendliness. The initiative for this was taken by the Kathak Kendra, Delhi, which organised a Workshop on Kathak from March 24 to 26 . It was a distinguished gathering. It l.ncluded Lachchhu Maharaj from Lucknow, Gauri Shankar, Mohanrao Kallianpurkar and Roshan Kumari from Bombay, Rohini Bhate and Prabha Marathe from Poona, Kumudini Lakhia from Ahmedabad, Sunderlal Gangani from the Sayajirao University, Baroda, P. D . Ashirwatham from the Indira Kala Sangeet Vidyalaya, Khairagarh, and Birju Maharaj, Kundanlal Gangani, Dr. Kapila Vatsyayan, Uma Sharma, Rani Karna, S. K . Saxena, Munna Shukla and Reba Vidyarthi from Delhi. There were a number of observers. The doyen of Kathaks, Lachchhu· Maharaj was the Chairman, and Mohanrao Kallianpurkar acted as the Director. 52 Lachchhu Maharaj demonstrating bhava On all the three days, the Workshop met in two sessions, from 1 0 . -

Annual Report 2009-2010

Annual Report NDIA NTERNATIONAL ENTRE I I I C -2010 ND 2009 I A I NTERNAT I ONAL C ENTRE Annual Report Annual 2009 INDIA INTERNATIONAL CENTRE -2010 40 Max Mueller Marg New Delhi 110 003 INDIA INTERNATIONAL CENTRE New Delhi Annual Report INDIA INTERNATIONAL CENTRE 2009-2010 INDIA INTERNATIONAL CENTRE New Delhi Board of Trustees Professor M.G.K. Menon, President Justice B. N. Srikrishna Dr. Kapila Vatsyayan Mr. L. K. Joshi Mr. Soli J. Sorabjee Professor S.K. Thorat Mr. N. N. Vohra Dr. Kavita A. Sharma Executive Members Dr. Kavita A. Sharma, Director Prof. Rajasekharan Pillai Mr. Kisan Mehta Dr. K.T. Ravindran Mr. Keshav N. Desiraju Mr. M.P. Wadhawan, Hon. Treasurer Lt. Gen. V.R. Raghavan Cmde. (Retd.) Ravinder Datta, Secretary Mr. Vipin Malik Finance Committee Dr. Shankar N. Acharya, Chairman Mr. M.P. Wadhawan, Hon. Treasurer Mr. Pradeep Dinodia, Member Mr. P.R. Sivasubramanian, Chief Finance Officer Lt. Gen. (Retd.) V.R. Raghavan, Member Cmde. (Retd.) Ravinder Datta, Secretary Dr. Kavita A. Sharma, Director Medical Consultants Dr. K.P. Mathur Dr. Rita Mohan Dr. K.A. Ramachandran Dr. B. Chakravorty Dr. Mohammad Qasim IIC Senior Staff Ms. Premola Ghose, Chief Programme Division Mr. A.L. Rawal, Dy. General Manager (C) Mr. Arun Potdar, Chief Maintenance Division Mrs. Shamole Aggarwal, Dy. General Manager (H) Mrs. Ira Pande, Chief Editor Mr. Inder Butalia, Sr. Finance and Accounts Officer Mr. Amod K. Dalela, Administration Officer Mrs. Sushma Zutshi, Librarian Mr. Vijay Kumar Thukral, Executive Chef Mr. K.S. Kutty, Membership Officer -2010 Annual Report 2009 It is my privilege to present the forty-ninth Annual Report of the India International Centre for the year commencing 1 February, 2009 and ending on 31 January, 2010.