Press Release Chris Killip Trabajo/Work

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

TPG Exhibition List

Exhibition History 1971 - present The following list is a record of exhibitions held at The Photographers' Gallery, London since its opening in January 1971. Exhibitions and a selection of other activities and events organised by the Print Sales, the Education Department and the Digital Programme (including the Media Wall) are listed. Please note: The archive collection is continually being catalogued and new material is discovered. This list will be updated intermittently to reflect this. It is for this reason that some exhibitions have more detail than others. Exhibitions listed as archival may contain uncredited worKs and artists. With this in mind, please be aware of the following when using the list for research purposes: – Foyer exhibitions were usually mounted last minute, and therefore there are no complete records of these brief exhibitions, where records exist they have been included in this list – The Bookstall Gallery was a small space in the bookshop, it went on to become the Print Room, and is also listed as Print Room Sales – VideoSpin was a brief series of worKs by video artists exhibited in the bookshop beginning in December 1999 – Gaps in exhibitions coincide with building and development worKs – Where beginning and end dates are the same, the exact dates have yet to be confirmed as the information is not currently available For complete accuracy, information should be verified against primary source documents in the Archive at the Photographers' Gallery. For more information, please contact the Archive at [email protected] -

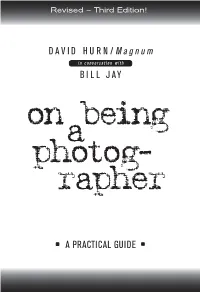

On Being a Photographer, 3Rd Edition

Photography/Photojournalism $12.95 USD Revised – Third Edition! “A photographer might forget his camera and live to tell the ON BEING A PHOTOGRAPHER tale. But no photographer who survives has ever forgotten the lessons in this book. It is not just essential reading, it’s compulsory.” DAVID HURN/Magnum Daniel Meadows Head of Photojournalism, Center for Journalism Studies, in conversation with University of Wales “A very useful book. It discusses issues which will benefit all BILL JAY photographers irrespective of type, age or experience – and it does so in a clear and interesting manner. I recommend it.” Van Deren Coke past Director of the International Museum of Photography and author of The Painter and the Photograph “I read On Being a Photographer in one sitting. This is an invaluable book for its historical and aesthetic references as well as David’s words, which go to the heart of every committed David Hurn/ on being photographer – from the heart of a great photographer. It is inspiring.” Frank Hoy Associate Professor, Visual Journalism, The Walter Cronkite School Magnum a of Journalism and Telecommunication, Arizona State University “We all take photographs but few of us are photographers. On Being a Photographer talks clearly and cogently about the difference … and Bill Jay photog- the book is rich in practical detail about how to practice as a photographer and to create worthwhile pictures.” Barry Lane past-Director of Photography at the Arts Council of Great Britain and presently Secretary-General rapher of The Royal Photographic -

Coversheet for Thesis in Sussex Research Online

A University of Sussex PhD thesis Available online via Sussex Research Online: http://sro.sussex.ac.uk/ This thesis is protected by copyright which belongs to the author. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the Author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the Author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Please visit Sussex Research Online for more information and further details 1 UNIVERSITY OF SUSSEX Alice Compton Ph.D Waste of a Nation: Photography, Abjection and Crisis in Thatcher’s Britain May 2016 2 ABSTRACT This examination of photography in Thatcher’s Britain explores the abject photographic responses to the discursive construction of ‘sick Britain’ promoted by the Conservative Party during the years of crisis from the late 1970s onwards. Through close visual analyses of photojournalist, press, and social documentary photographs, this Ph.D examines the visual responses to the Government’s advocation of a ‘healthy’ society and its programme of social and economic ‘waste-saving’. Drawing Imogen Tyler’s interpretation of ‘social abjection’ (the discursive mediation of subjects through exclusionary modes of ‘revolting aesthetics’) into the visual field, this Ph.D explores photography’s implication in bolstering the abject and exclusionary discourses of the era. Exploring the contexts in which photographs were created, utilised and disseminated to visually convey ‘waste’ as an expression of social abjection, this Ph.D exposes how the Right’s successful establishment of a neoliberal political economy was supported by an accelerated use and deployment of revolting photographic aesthetics. -

7.10 Nov 2019 Grand Palais

PRESS KIT COURTESY OF THE ARTIST, YANCEY RICHARDSON, NEW YORK, AND STEVENSON CAPE TOWN/JOHANNESBURG CAPE AND STEVENSON NEW YORK, RICHARDSON, YANCEY OF THE ARTIST, COURTESY © ZANELE MUHOLI. © ZANELE 7.10 NOV 2019 GRAND PALAIS Official Partners With the patronage of the Ministry of Culture Under the High Patronage of Mr Emmanuel MACRON President of the French Republic [email protected] - London: Katie Campbell +44 (0) 7392 871272 - Paris: Pierre-Édouard MOUTIN +33 (0)6 26 25 51 57 Marina DAVID +33 (0)6 86 72 24 21 Andréa AZÉMA +33 (0)7 76 80 75 03 Reed Expositions France 52-54 quai de Dion-Bouton 92806 Puteaux cedex [email protected] / www.parisphoto.com - Tel. +33 (0)1 47 56 64 69 www.parisphoto.com Press information of images available to the press are regularly updated at press.parisphoto.com Press kit – Paris Photo 2019 – 31.10.2019 INTRODUCTION - FAIR DIRECTORS FLORENCE BOURGEOIS, DIRECTOR CHRISTOPH WIESNER, ARTISTIC DIRECTOR - OFFICIAL FAIR IMAGE EXHIBITORS - GALERIES (SECTORS PRINCIPAL/PRISMES/CURIOSA/FILM) - PUBLISHERS/ART BOOK DEALERS (BOOK SECTOR) - KEY FIGURES EXHIBITOR PROJECTS - PRINCIPAL SECTOR - SOLO & DUO SHOWS - GROUP SHOWS - PRISMES SECTOR - CURIOSA SECTOR - FILM SECTEUR - BOOK SECTOR : BOOK SIGNING PROGRAM PUBLIC PROGRAMMING – EXHIBITIONS / AWARDS FONDATION A STICHTING – BRUSSELS – PRIVATE COLLECTION EXHIBITION PARIS PHOTO – APERTURE FOUNDATION PHOTOBOOKS AWARDS CARTE BLANCHE STUDENTS 2019 – A PLATFORM FOR EMERGING PHOTOGRAPHY IN EUROPE ROBERT FRANK TRIBUTE JPMORGAN CHASE ART COLLECTION - COLLECTIVE IDENTITY -

Martin Parr / April 2019 Solo Shows – Current and Upcoming

Martin Parr / April 2019 Solo Shows – Current and Upcoming Only Human: Martin Parr Wolfson and Lerner Galleries, National Portrait Gallery, London, UK 7 Mar to 27 May 2019 Further details here The National Portrait Gallery celebrates a major new exhibition of works by Martin Parr, one of Britain’s best-known and most widely celebrated photographers. Only Human: Martin Parr, brings together some of Parr’s best known photographs with new work by Parr never exhibited before, to focus on one of his most engaging subjects – people. Featuring portraits of people from around the world, the exhibition examines national identity today, both in the UK and abroad with a special focus on Parr’s wry observations of Britishness. Britain in the time of Brexit will be the focus of one section, featuring new works, which reveal Parr’s take on the social climate in the aftermath of the EU referendum. The exhibition will also focus on the British Abroad, including photographs made in British Army camps overseas, and Parr’s long term study of the British ‘Establishment’ including recent photographs taken at Christ’s Hospital school in Sussex, Oxford and Cambridge Universities and the City of London, revealing the obscure rituals and ceremonies of British life. Although best known for capturing ordinary people, Parr has also photographed celebrities throughout his career. For the first time Only Human: Martin Parr will reveal a selection of portraits of renowned personalities, most of which have never been exhibited before, including British fashion legends Vivienne Westwood and Paul Smith, contemporary artists Tracey Emin and Grayson Perry and world-renowned football player Pelé. -

Ends in 67 Days Closed Today (Tuesday)

Ends in 67 days Closed Today (Tuesday) L. Parker Stephenson Photographs celebrates its representation of John Davies (b. 1949) with the first solo exhibition of his work in the United States. Nominated for the Deutsche Börse prize in 2008, Davies is best known for his 1980s photographs documenting the broad, complex and changing topography of industrial and post- industrial Britain. Over a dozen large vintage and modern gelatin silver prints have been selected for presentation from his series The British Landscape (published in book format by Chris Boot, 2006). John Davies’ engagement with documentary photography emerged as a response to the economic and social upheavals taking place in the UK in the late 1970s and 80s. This important transitional era was examined in the Museum of Modern Art New York’s 1991 exhibition and accompanying catalog, British Photography from the Thatcher Years, which presented the work of John Davies, Paul Graham, Chris Killip, Martin Parr and Graham Smith. Davies’ exhibited images from A Green and Pleasant Land examined changes to the environment wrought on it by industrialization and urbanization. This 1986 title was the first book published by Dewi Lewis while he was Director of the Cornerhouse art center. Working through long-standing British traditions of painterly and literary scenes, Davies utilizes the sharp descriptive power of large format photography for his fine gelatin silver prints to include a range of details that exceeds a complacent reading of the terrain, emphasizing instead its flux. He honors and preserves the layers of cultural history while the past is regularly erased and replaced. -

The Troublesome Document

Virginia Commonwealth University VCU Scholars Compass Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 2014 The Troublesome Document Stanley Wolukau-Wanambwa Virginia Commonwealth University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/etd Part of the Photography Commons © The Author Downloaded from https://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/etd/3475 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at VCU Scholars Compass. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of VCU Scholars Compass. For more information, please contact [email protected]. © Stanley Wolukau-Wanambwa - 2014 All Rights Reserved The Troublesome Document A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Fine Arts in Photography & Film at Virginia Commonwealth University. by Stanley Wolukau-Wanambwa BA Double Hons. Oxford University, 2002 Director: Brian Ulrich, Associate Professor, Department of Photography & Film Virginia Commonwealth University Richmond, Virginia, April 2014 ii Table of Contents Abstract…………………………………………………………………………………...iv Section I. The Problematic Document…………………………………………………….1 Section II. A Period of Transition: From Picture Press to Photobook…………………...18 Section III. The Virtues of Documentary Photography………………………………….40 Section IV. Illustrations………………………………………………………………….45 iii Abstract THE TROUBLESOME DOCUMENT By Stanley Wolukau-Wanambwa, BA Double Hons A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Fine Arts in Photography & Film at Virginia Commonwealth University. Virginia Commonwealth University, 2014. Director: Brian Ulrich, Associate Professor, Department of Photography & Film Virginia Commonwealth University Richmond, Virginia, April 2014 An essay concerning the development of documentary photography, its relationship to political norms, conventions of realism in visual culture, and the form of the photographic book. -

Exhibition History, 1971 - Present

EXHIBITION HISTORY, 1971 - PRESENT The following list is a record of exhibitions held at The Photographers' Gallery, London since its opening in January 1971. Exhibitions and events organised by the Print Sales, the Education Department and the Digital Programme (Wall) are included. Please note: The archive collection is continually being catalogued and new material is discovered. This list will be updated intermittently to reflect this. It is for this reason that some exhibitions have more detail than others. Exhibitions listed as archival may contain uncredited works and artists. With this in mind, please be aware of the following when using the list for research purposes: – Foyer exhibitions were usually mounted last minute, and therefore there are no complete records of these brief exhibitions, where records exists they have been included in this list – The Bookstall Gallery was a small space in the bookshop, it went on to become the Print Room, and is also listed as Print Room Sales – VideoSpin was a brief series of works by video artists exhibited in the bookshop beginning in December 1999 – Gaps in exhibitions coincide with building and development works – Where beginning and end dates are the same, the exact dates have yet to be confirmed as the information is not currently available For complete accuracy, information should be verified against primary source documents in the Archive Room at the Photographers' Gallery. For more information, please contact the archive at [email protected] 1970s Group Exhibition Date: 13/01/1971 -

Seeing Colonially: Martin Parr, John Thomson and the British Photographic Imagination

Seeing Colonially: Martin Parr, John Thomson And The British Photographic Imagination by Cammie Jo Tipton-Amini A thesis submitted to the Kathrine G. McGovern College of the Arts in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Art History Chair of Committee: Natilee Harren Committee Member: Roberto Tejada Committee Member: Sandra Zalman University of Houston May 2021 DEDICATION To my grandmother Ruby Anna Wilson and my husband Farhang Amini. ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to thank the following people for their help and support throughout this project. Special thanks to Dr. Harren for the continued support and challenges, equally. Thank you Dr. Tejada and Dr. Zalman for your thoughtful edits, suggestions, recommendations and support. Heartfelt gratitude goes to Dr. Ari for introducing me to postcolonial studies and nineteenth century photography and for taking the time to make me a better writer. Lastly, big respect goes to each in my cohort, Ana, Chesli, Lindsey and Sheri, as we labored through a pandemic, Zoom-school, and local and global catastrophes, to accomplish what we came for. iii ABSTRACT The British contemporary photographer Martin Parr’s collection 7 Colonial Still Lifes (2005) delivers banal and benign images of remnants of British colonization in Sri Lanka. Parr’s early collection The Last Resort (1986) was harshly critiqued for its judgmental lens of the working-class British, with some identifying a contemporary “othering” in Parr’s imagery, yet this line of reasoning was never explored fully. I form a postcolonial reading to argue that what Parr’s critics sensed was the historical legacy of British colonial photography. -

Modern Nature / British Photographs from The

MODERN NATURE / BRITISH PHOTOGRAPHS FROM THE HYMAN COLLECTION 13 July 2018 – 22 April 2019 FREE ADMISSION Daniel Meadows National Portrait (Three Boys and a Pigeon) 1974 ‘From the deep indigo and black scarlets of the industrial heart we sailed through the unimaginable beauty of unspoiled countryside. These conflicting landscapes really shaped, I think, my whole life.’ - Barbara Hepworth on growing up in Wakefield For the first time in human history, more people are living in urban environments than in the countryside, yet the impulse to seek out nature remains as strong as ever. This new exhibition of photographs by leading British photographers such as Shirley Baker, Bill Brandt, Anna Fox, Chris Killip, Martin Parr and Tony Ray-Jones explores our evolving relationship with the natural world and how this shapes individuals and communities. Drawn from the collection of Claire and James Hyman, which comprises more than 3,000 photographs ranging from conceptual compositions to documentary-style works, Modern Nature will include around 60 photographs taken since the end of the Second World War, through the beginnings of de-industrialisation to the present day. It will explore the merging of urban and rural landscapes, the rapid expansion of cities and the increasingly intrusive management of the countryside. A number of photographs on display, including The Caravan Gallery’s quizzical views of urban centres and Chris Shaw’s ‘Weeds of Wallasey’ series (2007–12), capture the ways in which nature infiltrates the city. Others, such as Mark Power’s ‘The Shipping Forecast’ series (1993–6) and Marketa Luskacova’s NE Seaside (1978) images document trips out to the coast and countryside, driven by the sometimes powerful need to escape urban life. -

Nick Blackburn OCA #518937 Expressing Your Vision Final

Nick Blackburn - OCA #518937 - Expressing Your Vision - Final Assessment Submission Nick Blackburn OCA #518937 Expressing your vision Final Assessment Submission Full online text Nick Blackburn - OCA #518937 - Expressing Your Vision - Final Assessment Submission Contents Item Description Date of original 1 Introduction 18Dec19 2 Assignment 1 submission 01Sep18 3 Assignment 1 tutor feedback 15Sep18 4 Assignment 2 submission 01Dec18 5 Assignment 2 tutor feedback 10Dec18 6 Assignment 3 submission 01Mar19 7 Assignment 3 tutor feedback 11Mar19 8 Assignment 3 rework 14Mar19 9 Assignment 4 submission 01Jul19 10 Assignment 4 tutor feedback 08Jul19 11 Assignment 4 rework 13Jul18 12 Assignment 5 submission 01Oct19 13 Assignment 5 tutor feedback 10Oct19 14 Assignment 5 rework 26Oct19 15 Exercise 4.5 29Mar19 16 Exercise 5.2 19Jul19 17 Learning log, Part 1 08Aug18 18 Learning log, Part 2 24Sep18 19 Learning log, Part 3 10Dec18 20 Learning log, Part 4 29Mar19 21 Learning log, Part 5 19Aug19 22 Course Blog, Part 1, 2018 27Dec18 23 Course Blog, Part 2, 2019 18Dec19 Nick Blackburn - OCA #518937 - Expressing Your Vision - Final Assessment Submission 1. Introduction I am a person of age and mostly retired. Having taken photographs for the last 50 years, and finding my images and choices of subjects moribund, I started the degree course in order to expand my subject range and to gain some formal (that is, academic) understanding of what I am doing and why. I have enjoyed Expressing your vision immensely and intend to continue studying. I have found it difficult to determine what this final submission should actually comprise: the Context and Narrative course, in contrast, states the requirements quite explicitly. -

Photographer Report & Presentation

photojournalism basics professor ripka ASSIGNMENT PHOTOGRAPHER REPORT INSTRUCTIONS & PRESENTATION Using the list of photographers, you will create a 3–4 page report and a presentation on a photographer of your choice. HANDING IN: 1. Select a photographer from the provided list of photographers. Look at multiple Submit your report and slide deck to ICON photographers, not just the frst one you fnd. Make sure you like their work. Once you have selected a photographer, notify instructor for approval via email. No two people may do the same photographer. First to notify takes precedence. A google spreadsheet will be created by instructor so you can see who has been claimed. 2. Select three photos you like (or hate) by your photographer to analyze. NOTE: This will be due the week after this project is assigned as you will use these photos to explore various aspects of photography during lectures. Be sure to have jpgs of the photos. 3. Find out about your photographer. Write no more than a paragraph or two recapitu- lating their career, viewpoints, and major subject matter. 4. For each photo, research when/where/why the image was made and list 2-3 of the news values that this photograph hits. Those news values are: • Timeliness • Proximity • Impact • Magnitude • Prominence • Confict • Novelty • Emotional Appeal 5. For each photo, its composition, photographic techniques, and lighting. You should discuss no less than 10 of the concepts we have covered. Do not merely describe the photo. Do not insert the photos to your written report as they will be in the slide deck.