Gender Fictions and the Discourse of Hygiene In

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Televisión Y Literatura En La España De La Transición (1973-1982)

Antonio Ansón, Juan Carlos Ara Torralba, José Luis Calvo Carilla, Luis Miguel Fernández, María Ángeles Naval López y Carmen Peña Ardid (Eds.) Televisión y Literatura en la España de la Transición (1973-1982) COLECCIÓN ACTAS f El presente libro recoge los trabajos del Seminario «Televisión y Literatura en la España de la Transición» que, bajo el generoso patrocinio de la Institución ACTAS «Fernando el Católico», tuvo lugar durante los días 13 a 16 de febrero de 2008. En él se incluyen, junto con las aportaciones del Grupo de Investigación sobre «La literatura en los medios de comunicación de masas durante COLECCIÓN la Transición, 1973-1982», formado por varios profesores de las Universidades de Zaragoza y Santiago de Compostela, las ponencias de destacados especialistas invitados a las sesiones, quienes han enriquecido el resultado final con la profundidad y amplitud de horizontes de sus intervenciones. El conjunto de todos estos trabajos representa un importante esfuerzo colectivo al servicio del mejor conocimiento de las relaciones entre el influyente medio televisivo (único en los años que aquí se estudian) y la literatura en sus diversas manifestaciones creativas, institucionales, críticas y didácticas. A ellos, como segunda parte del volumen, se añade una selección crítica de los principales programas de contenido literario emitidos por Televisión Española durante la Transición, con información pormenorizada sobre sus características, periodicidad, fecha de emisión, banda horaria y otros aspectos que ayudan a definir su significación estética y sociológica. Diseño de cubierta: A. Bretón. Motivo de cubierta: Josep Pla entrevistado en «A fondo» (enero de 1977). La versión original y completa de esta obra debe consultarse en: https://ifc.dpz.es/publicaciones/ebooks/id/2957 Esta obra está sujeta a la licencia CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 Internacional de Creative Commons que determina lo siguiente: • BY (Reconocimiento): Debe reconocer adecuadamente la autoría, proporcionar un enlace a la licencia e indicar si se han realizado cambios. -

"Beautiful All Year Round"

Translated articles · Eme n 2 · 2014 102 Martin Salisbury · pp. 100-103. ISSN 2253-6337 Raquel Pelta Resano · pp. 103-110. ISSN 2253-6337 103 Translated articles · Eme n 2 · 2014 as objects in mind, to that end we do everything tion exhibition in London, in 2003 she set up her Cambridge School of Art, I see an increasing number Gilmour, Pat: Artists at Curwen, London, Tate in our power to ensure that they look good, smell company ‘Donna Wilson’, creating designs for of Masters students applying their work to a range of Gallery, 1977. good and most of all tell great stories!” cushion covers, blankets, soft toys etc. In 2010 she design contexts beyond the book. I am showing a few Salisbury, Martin: Artists at the Fry, Cambridge, As well as independent publishers such as No- was named Designer of the Year by the magazine, examples here. In the early stages of this course, stu- Ruskin Press/Fry Art Gallery and Museum, 2003. brow, small ‘private press’ printer- publishers still Elle Decoration. The studio now employs a team dents devote their time to self-proposed thematic ob- Bacon, CAROLINE AND MCGregor, James: seem to be thriving. But one of the most noticeable of workers making enough of Donna’s designs to servational drawing projects. Even at this early stage Edward Bawden, Bedford, Cecil Higgins Art gal- examples of a return to aspects of the mid-Twen- meet the demand from major high street stores of making acquaintance with their individual meth- lery, 2008. tieth ethos is the branching out of illustrators into such as John Lewis. -

Orientalisms the Construction of Imaginary of the Middle East and North Africa (1800-1956)

6 march 20 | 21 june 20 #IVAMOrientalismos #IVAMOrientalismes Orientalisms The construction of imaginary of the Middle East and North Africa (1800-1956) Francisco Iturrino González (Santander, 1864-Cagnes-sur-Mer, Francia, 1924) Odalisca, 1912. Óleo sobre lienzo, 91 x 139 cm Departament de Comunicació i Xarxes Socials [email protected] Departament de Comunicació i Xarxes Socials 2 [email protected] DOSSIER Curators: Rogelio López-Cuenca Sergio Rubira (IVAM Exhibitions and Collection Deputy Director) MªJesús Folch (assistant curator of the exhibition and curator of IVAM) THE EXHIBITION INCLUDES WORKS BY ARTISTS FROM MORE THAN 70 PUBLIC AND PRIVATE COLLECTIONS Francisco de Goya y Lucientes (National Calcography), Francisco Lamayer, César Álvarez Dumont, Antonio Muñoz Degrain (Prado Museum), José Benlliure (Benlliure House Museum), Joaquín Sorolla (Sorolla Museum of Madrid), Rafael Senet and Fernando Tirado (Museum of Fine Arts of Seville), Mariano Bertuchi and Eugenio Lucas Velázquez (National Museum of Romanticism), Marià Fortuny i Marsal (Reus Museum, Tarragona), Rafael de Penagos (Círculo de Bellas Artes de Madrid, Institut del Teatre de Barcelona, MAPFRE Collection), Leopoldo Sánchez (Museum of Arts and Customs of Seville), Ulpiano Checa (Ulpiano Checa Museum of Madrid), Antoni Fabrés (MNAC and Prado Museum), Emilio Sala y Francés and Joaquín Agrasot (Gravina Palace Fine Arts Museum, Alacant), Etienne Dinet and Azouaou Mammeri (Musée d’Orsay), José Ortiz Echagüe (Museum of the University of Navarra), José Cruz Herrera (Cruz Herrera -

Greater San Diego Hunter Jumper Association

Greater San Diego Hunter Jumper Association Established 2001 ! RULE BOOK Effective: December 1, 2020 !1 TABLE OF CONTENTS RULES AND REGULATIONS RULE I - MEMBERSHIP RULE II - EXHIBITORS, RIDERS, AND TRAINERS RULE III – PROTESTS AND RULE AMENDMENTS RULE IV - EQUITATION DIVISION RULE V - AGE EQUITATION RULE VI - GSDHJA MEDAL CLASSES RULE VII – HUNTER DIVISION RULE VIII –JUMPER DIVISION RULE IX – COMBINING/DIVIDING SECTIONS RULE X - CHAMPIONSHIP SHOW ELIGIBILITY RULE XI – YEAR END AWARDS All rule changes are effective December 1, 2020, unless otherwise specified, for the 2021 competition year. Rule book may be downloaded on www.gsdhja.org. !2 2021 RULES AND REGULATIONS OF THE GREATER SAN DIEGO HUNTER AND JUMPER ASSOCIATION All horse shows recognized by the Greater San Diego Hunter and Jumper Association, Inc. ("GSDHJA") and every person participating at the competition including exhibitor, owner, lessee, manager, agent, rider, handler, judge, steward, competition official, or employee is subject to the rules of the GSDHJA. In the event a show member of this Association is also a regular member competition of United States Equestrian Federation, Inc. ("USEF") and there is a conflict of rules, the rules of USEF shall prevail. In the event a show member of this Association (held within the boundaries of the state of California) is also a show member of another horse show association other than USEF and there is a conflict of rules, the rules of the GSDHJA shall prevail. Rule I- MEMBERSHIP PART I - MEMBERS The membership year is from November 1, 2017 until November 1, 2018. Section 1. INDIVIDUAL MEMBERS consist of those persons or business who becomes a member upon filing an application for membership and paying the dues fixed by the Association. -

Hunt Seat Equitation Amateur

Table of Contents Hunt Seat Equitation Amateur . 4 Showmanship Masters Amateur Finals . 18 Hunt Seat Equitation Amateur Solid Paint-Bred . 3 Showmanship Masters Amateur Preliminaries . 16 Hunt Seat Equitation Amateur Walk-Trot . 2 Showmanship Novice Amateur . 15 Hunt Seat Equitation Masters Amateur . 4 Trail Amateur . 21 Hunt Seat Equitation Novice Amateur . 3 Trail Amateur Walk-Trot . 19 Hunt Seat Equitation Over Fences Amateur . 5 Trail Green . 25 Hunt Seat Equitation Over Fences Novice Amateur . 6 Trail Junior . 22 Hunt Seat Equitation Over Fences Warm-Up . 5 Trail Masters Amateur . 21 Hunter Hack Amateur . 7 Trail Novice Amateur . 20 Hunter Hack Junior . 7 Trail Open Solid Paint-Bred . 26 Hunter Hack Novice Amateur . 7 Trail Senior Finals . 24 Hunter Hack Senior . 7 Trail Senior Preliminaries . 23 Jumping Amateur . 8 Trail Yearling In-Hand Amateur . 27 Jumping Open . 8 Trail Yearling In-Hand Amateur Solid Paint-Bred . 27 Jumping Warm-Up . 8 Trail Yearling In-Hand Breeders’ Futurity Gold . 29 Ranch Pleasure Amateur . 1 Trail Yearling In-Hand Open . 28 Ranch Pleasure Novice Amateur . 1 Trail Yearling In-Hand Open Solid Paint-Bred . 28 Ranch Pleasure Open . 1 Trail 3-Year-Old Sweepstakes . 30 Ranch Riding Amateur . 9 Trail 4- & 5-Year-Old Sweepstakes . 31 Ranch Riding Amateur Solid Paint-Bred . 9 Utility Driving . 32 Ranch Riding Novice Amateur . 9 Western Horsemanship Amateur . 35 Ranch Riding Open . 10 Western Horsemanship Amateur Solid Paint-Bred . 34 Ranch Riding Open Solid Paint-Bred . 10 Western Horsemanship Amateur Walk-Trot . 33 Ranch Trail Amateur . 12 Western Horsemanship Masters Amateur . 35 Ranch Trail Amateur Solid Paint-Bred . -

The Leading Equestrian Magazine in the Middle East

48 WINTER 2015 THE LEADING EQUESTRIAN MAGAZINE IN THE MIDDLE EAST Showjumping I Profiles I Events I Dressage I Training Tips I Legal VIEW POINT FROMFROM THETHE CHAIRMANCHAIRMAN Metidji and Mrs. Fahima Sebianne, our equestrian sport, we were proud to president of the ground jury, for their co-sponsor and cover the “SOFITEL extreme dedication and hopeful vision. Cairo El Gezirah Hotel Horse Show” held at the Ferousia Club and to give In this issue, we present for your you a look at the opening of Pegasus consideration an expert legal analysis Equestrian Centre in Dreamland, a of the issues related to the Global significant and impressive addition to Champions Tour versus the FEI in the nation’s riding facilities. a struggle for control of the sport. Dear Readers, And all way from Spain, we bring We would like to share with you as you highlights of the Belgian team at well special interviews with Egyptian I would like to start by wishing you a the Furusiyya FEI Nations Cup™. horse riders: Amina Ammar, the Merry Christmas and a Happy New leading lady riding at top levels and Year to you and your beloved families. With more focus on technical training, Mr. Ahmed Talaat, the leading figure in we bring you Emad Zaghloul’s course designing representing Egypt dressage article on impulsion and The development of the equestrian internationally. sport is intensifying worldwide and the importance of such principle in particularly in the Middle East, where all equestrian disciplines. Moving on To better complement our storytelling, the rate of progress is remarkable. -

Pla De Comunicació Del Producte Turisme Eqüestre a Menorca

PLA DE COMUNICACIÓ DEL PRODUCTE TURISME EQÜESTRE A MENORCA Madrid, 30 Novembre de 2009 Pla de Comunicació elaborat per: 1 Pla de Comunicació del Producte Turisme Eqüestre a Menorca INDEX 1. Antecedents ............................................................................................ 3 2. Metodologia ............................................................................................ 7 3. La comunicació turística ......................................................................... 10 3.1. La publicitat ..................................................................................... 11 3.2. Les promocions ............................................................................... 12 3.3. Les relacions públiques ................................................................... 12 3.4. La venda personal ........................................................................... 13 4. Tendència del turisme eqüestre i els seus mercats emissors ................. 15 4.1. Les destinacions de turisme eqüestre. Centres emissors, receptors i operadors turístics d’intermediació ........................................ 17 4.2. Operadors i rutes de turisme eqüestre ............................................. 18 5. El mercat de turisme eqüestre a Espanya .............................................. 22 5.1. Dades generals del mercat ............................................................... 23 5.2. Anàlisi del turisme eqüestre a Espanya ........................................... 40 5.3. Operadors, empreses -

IDA Dressage Seat Equitation Class Score Sheet

IDA Dressage Seat Equitation Class Score Sheet Purpose: To evaluate the dressage rider’s correct position, seat and use of aids. See back of score sheet for rules and additional specifications. Judges’ Directives: Judges are required to give a final percentage score for all riders competing in each class. ***Only the “TOTAL SCORE” and “Place” columns are REQUIRED to be marked for EACH rider.*** Rider No. Walk Trot Canter Additional Score Place (Notes) (Notes) (Notes) Tests (Notes) (Percentage) Judge’s Name _________________________________ Judge’s Signature _________________________ Dressage Seat Equitation Classes 90-100 Excellent May be ridden as a group: No major position flaw. Exceptional basics. The judge should describe this rider using only superlatives. The judge must not be afraid to use this score when it is 1. Free walk appropriate. 2. Transitions from one gait to the next in both directions. 85-89 Very Good 3. Transitions from walk to halt and vice versa. No major position flaw. Very good basics. This rider might have one of the minor 4. Change of direction across the diagonal, down the centerline, flaws listed above to a minor degree. Ideally most of the winners will receive score across the arena, in the 80’s. and/or making a half-circle at the walk or trot 5. W/T/C both ways of the arena (no canter for Intro) 80-84 No major position flaws and very good basics. This rider might have one of the minor flaws listed above to a greater degree or have a couple to a less degree. Additional tests from which judges may choose movements and exercises, ridden in small groups. -

Rules & Regulations 2018

RULES & REGULATIONS 2018 2018 Southern Regional 4-H Horse Championships Georgia National Fairgrounds and Agricenter, Perry, GA August 1-5, 2018 Wednesday, August 1 Roquemore 8:00am Hippology Contest Check In 8:00am Check-in Opens 8:30am Hippology Contest Begins Exhibitors begin move in 2:00pm Horse Bowl Contest Check In 2:30pm Horse Bowl Contest Begins 6:00pm Upload Oral Presentations 8:00pm Staff dinner and orientation Thursday, August 2 Roquemore Reaves Arena 7:00am Oral Presentation Contest Check In 8:30am Horse Judging Contest Check In 7:30am Oral Presentation Contest Begins 9:30am Horse Judging Contest Begins Sutherland, Hunter 2:00pm Reaves Arena, Saddle/Gaited 9:30 set up jump course DQP 32. Gaited Equitation 12:00pm – 5:00pm Schooling over Fences 29. Gaited Pleasure (Walking Horse Type) 5:00pm-6:30pm schooling for Ed. contestants 30. Gaited Pleasure (Racking Horse Type) 31. Gaited Pleasure (Non-Walking/Racking 1:00pm Practice Ring #2, Western Type) 23. Western Trail* 28. Saddle Seat Equitation (assigned order of go) 27. Saddle Seat Pleasure *Exhibitors may enter the same horse in both Western Trail and Ranch Trail. 7:00pm Parade of States Reaves Arena Awards: Educational Contests Exhibitor social immediately following north wing of Reaves Friday, August 3 Sutherland, Hunter 7:00-10:00am Schooling Over Fences 8:00am Practice Ring #2 Gaited/Saddle (assigned order of go) (no DQP) 5. Saddle Type Mares (Trotting) 10:30am 6. Saddle Type Geldings (Trotting) 35.Working Hunter 10. Saddle Type Showmanship 36.Equitation Over Fences 7. Gaited Mares 37. Jumping 8. Gaited Geldings 11. -

Canadian Show Jumping Team

CANADIAN SHOW JUMPING TEAM 2020 MEDIA GUIDE Introduction The Canadian Show Jumping Team Media Guide is offered to all mainstream and specialized media as a means of introducing our top athletes and offering up-to-date information on their most recent accomplishments. All National Team Program athletes forming the 2020 Canadian Show Jumping Team are profiled, allowing easy access to statistics, background information, horse details and competition results for each athlete. We have also included additional Canadian Show Jumping Team information, such as past major games results. The 2020 Canadian Show Jumping Team Media Guide is proudly produced by the Jumping Committee of Equestrian Canada, the national federation responsible for equestrian sport in Canada. Table of Contents: Introduction 2 2020 Jumping National Team Program Athletes 3 Athlete Profiles 4 Chef d’équipe Mark Laskin Profile 21 Major Games Past Results 22 Acknowledgements: For further information, contact: Editor Karen Hendry-Ouellette Jennifer Ward Manager of Sport - Jumping Starting Gate Communications Inc. Equestrian Canada Phone (613) 287-1515 ext. 102 Layout & Production [email protected] Starting Gate Communications Inc. Photographers Equestrian Canada Arnd Bronkhorst Photography 11 Hines Road ESI Photography Suite 201 Cara Grimshaw Kanata, ON R&B Presse K2K 2X1 Sportfot CANADA Starting Gate Communications Phone (613) 287-1515 Toll Free 1 (866) 282-8395 Fax (613) 248-3484 On the Cover: www.equestrian.ca Beth Underhill and Count Me In 2019 Canadian Show Jumping Champions by Starting Gate Communications 2020 Jumping National Team Program Athletes The following horse-and-rider combinations have been named to the 2020 Jumping National Team Program based on their 2019 results: A Squad 1 Nicole Walker ...................................................................... -

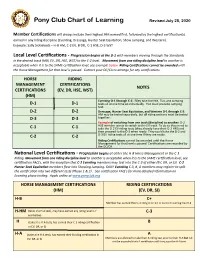

Pony Club Chart of Learning Revised July 28, 2020

Pony Club Chart of Learning Revised July 28, 2020 Member Certifications will always include their highest HM earned first, followed by the highest certification(s) earned in any riding discipline (Eventing, Dressage, Hunter Seat Equitation, Show Jumping, and Western). Example: Sally Sicklehock – H-B HM, C-2 EV, B DR, C-1 HSE, D-3 WST Local Level Certifications- Progression begins at the D-1 with members moving through the Standards in the desired track (HM, EV, DR, HSE, WST) to the C-2 level. Movement from one riding discipline level to another is acceptable when it is to the SAME certification level, see example below. Riding Certifications cannot be awarded until the Horse Management for that level is passed. Contact your DC/CA to arrange for any certifications. HORSE RIDING MANAGEMENT CERTIFICATIONS NOTES CERTIFICATIONS (EV, DR, HSE, WST) (HM) Eventing-D-1 through C-2: May take the HM, Flat, and Jumping D-1 D-1 tests all at one time or individually. Flat must precede Jumping test. D-2 D-2 Dressage, Hunter Seat Equitation, and Western -D 1 through C-2: HM may be tested separately, but all riding sections must be tested together. D-3 D-3 Example of switching from one track (discipline) to another: D-2 HSE member wants to switch to the EV track. To do so they need to C-1 C-1 take the D-2 EV riding tests (they already have their D-2 HM) and then proceed to the D-3 when ready. They could take the D-2 and D-3 EV riding tests all at one time if they are ready. -

Equestrian Majors at Wilson the Equestrian Industry Has an Annual Economic Impact That Exceeds One Billion Dollars

WILSON COLLEGE Programs for Equestrians I love the trainers and instructors at Wilson. “ They are accepting of all personal goals and sincerely work hard to get you there. Riding in lessons with Dr. Tukey that specialize in eventing made it possible for me to take my horse to his first event this past year. We continue to excel through the program and I have Wilson and Dr. Tukey to thank for these accomplishments.” Katie Douglas ‘08 Chesapeake Beach, MD Major: Equestrian Management & Equine Management Programs for Equestrians Wilson College provides rigorous study in the liberal arts and sciences and strong preparation for careers in the equine world as well as other fields. All students complete requirements in the sciences, humanities and social sciences. Wilson students develop, among others, effective skills in written and oral communication, the power to think and reason critically and the appreciation of cultural differences. Most Wilson students, including those majoring in Equestrian Studies or Equine Facilitated Therapeutics, select one or more minors that provide in-depth study outside of their major field. Some students choose to complete degree requirements for two majors with the understanding that this may take them more than four years. Whether you wish to pursue a degree or an eventual career in the equine world or want to continue riding while majoring in another discipline, Wilson College can fulfill those objectives. Wilson makes it easy for students to pursue their equestrian interests because, unlike many colleges with equestrian offerings, our facilities are part of our beautiful 300-acre campus, just a short walk from our residence halls.