I. Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Emi Nakamura Recipient of the 2014 Elaine Bennett Research Prize

Emi Nakamura Recipient of the 2014 Elaine Bennett Research Prize EMI NAKAMURA, Associate Professor of Business and Economics at Columbia University, is the recipient of the 2014 Elaine Bennett Research Prize. Established in 1998 by the American Economic Association’s (AEA) Committee on the Status of Women in the Economics Profession (CSWEP), the Elaine Bennett Research Prize recognizes and honors outstanding research in any field of economics by a woman not more than seven years beyond her Ph.D. Professor Nakamura will formally accept the Bennett Prize at the CSWEP Business Meeting and Luncheon held during the 2015 AEA Meeting in Boston, MA. The event is scheduled for 12:30-2:15PM on January 3, 2015 at the Sheraton Boston. Emi Nakamura’s distinctive approach tackles important research questions with serious and painstaking data work. Her groundbreaking paper “Five Facts about Prices: A Reevaluation of Menu Cost Models” (Steinsson, Jón and Emi Nakamura. 2008. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 123:4, 1415-1464) is based on extensive analysis of individual price data. She finds that, once temporary sales are properly taken into account, prices exhibit a high degree of rigidity consistent with Keynesian theories of business cycles and that prior evidence overstated the degree of price flexibility in the economy. Dr. Nakamura’s work on fiscal stimulus combines a novel cross-section approach to identifying parameters with a careful interpretation of business cycle theory to shed new light on crucial questions in macroeconomics. Her findings imply that government spending can provide a powerful stimulus to the economy at times when monetary policy is unresponsive, e.g. -

Committee on the Status of Women in the Economics Profession

Newsletter of the Committee on the Status of Women in the Economics Profession Winter 2006 Published three times annually by the American Economic Association’s Committee on the Status of Women in the Economics Profession Report of the Committee CONTENTS on the Status of Women 2005 Annual Report: 1, 3–8 in the Economics Claudia Goldin Receives 2005 Carolyn Shaw Bell Award: 1, 14 Profession 2005 Interview with Marianne Bertrand: 1, 14–15 —Submitted by Francine D. Blau From the Chair: 2 The Committee on the Status of Women in the Feature Articles: Teaching Economics in Economics Profession (CSWEP) was estab- Different Environments: 9–14 lished by the American Economic Association CSWEP Gender Sessions Summaries ASSA (AEA) in 1971 to monitor the status of wom- 2006: 16 en in the profession and formulate activities CSWEP Non-Gender Sessions Summaries ASSA to improve their status. This report begins by 2006: 18 summarizing trends in the representation of An Interview with women in the economics profession focus- Southern Economic Association Meeting ing particularly on the past decade. It then Marianne Bertrand, CSWEP Session Summaries: 20 takes a more detailed look at newly collected 2004 Elaine Bennett Southern Economic Association Meeting data for the current year and summarizes the Call for Papers: 21 Committee’s activities over the past year. Research Award Winner Eastern Economic Association Annual continued on page 3 The Elaine Bennett Research Prize is given Meeting CSWEP Sessions: 22 every two years to recognize, support and en- Midwest Economic Association Annual Claudia Goldin Receives courage outstanding contributions by young Meeting CSWEP Sessions: 22 women in the economics profession. -

Quarterly Journal of Economics Gratefully Acknowledges the Help of the People Listed Below Who Refereed One Or More Papers Between August 1, 2002, and July 31, 2003

THE QUARTERLY JOURNAL OF Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/qje/issue/118/4 by guest on 02 October 2021 ECONOMICS VOLUME CXVIII Board of Editors Alberto Alesina Edward L. Glaeser Lawrence F. Katz Assistant Editor Harriet E. Hoffman PUBLISHED FOR HARVARD UNIVERSITY BY THE MIT PRESS, CAMBRIDGE, MASSACHUSETTS 2003 CONTENTS FOR VOLUME CXVIII Authors Page AMERIKS, JOHN, ANDREW CAPLIN, AND JOHN LEAHY. Wealth Accumulation and the Propensity to Plan 1007 ANTRAS, POL. Firms, Contracts, and Trade Structure 1375 Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/qje/issue/118/4 by guest on 02 October 2021 ARIELY, DAN, GEORGE LOEWENSTEIN, AND DRAZEN PRELEC. "Coherent Arbitrari- ness": Stable Demand Curves without Stable Preferences 73 ÄSLUND, OLOF, PER-ANDERS EDIN, AND PETER FREDRIKSSON. Ethnic Enclaves and the Economic Success of Immigrants—Evidence from a Natural Experi- ment 329 ATTANASIO, ORAZIO P., AND AGAR BRUGIAVINI. SOCial Security and Households' Saving 1075 AUTOR, DAVID H., AND MARK G. DUGGAN. The Rise in the Disability Rolls and the Decline in Unemployment 157 AUTOR, DAVID H., FRANK LEVY, AND RICHARD J. MURNANE. The Skill Content of Recent Technological Change: An Empirical Exploration 1279 BAKER, MALCOLM, JEREMY C. STEIN, AND JEFFREY WURGLER. When Does the Market Matter? Stock Prices and the Investment of Equity-Dependent Firms 969 BERTRAND, MARIANNE, AND ANTOINETTE SCHOAR. Managing with Style: The Effect of Managers on Firm Policies 1169 BLANCHARD, OLIVIER AND FRANCESCO GIAVAllI. Macroeconomic Effects of Regu- lation and Deregulation in Goods and Labor Markets 879 BORJAS, GEORGE J. The Labor Demand Curve Is Downward Sloping: Reexamin- ing the Impact of Immigration on the Labor Market 1335 BRUGIAVINI, AGAR, AND ORAZIO P. -

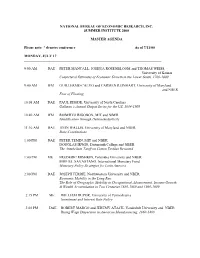

C:\Program Files\Adobe\Acrobat 4.0\Acrobat\Plug Ins\Openall\Transform\Temp\Masteragenda.Wpd

NATIONAL BUREAU OF ECONOMIC RESEARCH, INC. SUMMER INSTITUTE 2000 MASTER AGENDA Please note: * denotes conference As of 7/11/00 ____________________________________________________________________________ MONDAY, JULY 17 ____________________________________________________________________________ 9:00 AM DAE PETER MANCALL, JOSHUA ROSENBLOOM and THOMAS WEISS, University of Kansas Conjectural Estimates of Economic Growth in the Lower South, 1700-1800 9:00 AM IFM GUILLERMO CALVO and CARMEN REINHART, University of Maryland and NBER Fear of Floating 10:05 AM DAE PAUL RHODE, University of North Carolina Gallman’s Annual Output Series for the US, 1834-1909 10:40 AM IFM ROBERTO RIGOBON, MIT and NBER Identification through Heteroskedasticity 11:10 AM DAE JOHN WALLIS, University of Maryland and NBER State Constitutions 1:00 PM DAE PETER TEMIN, MIT and NBER DOUGLAS IRWIN, Dartmouth College and NBER The Antebellum Tariff on Cotton Textiles Revisited 1:00 PM ME FREDERIC MISHKIN, Columbia University and NBER MIGUEL SAVASTANO, International Monetary Fund Monetary Policy Strategies for Latin America 2:00 PM DAE JOSEPH FERRIE, Northwestern University and NBER Economic Mobility in the Long Run: The Role of Geographic Mobility in Occupational Advancement, Income Growth, & Wealth Accumulation in Two Centuries,1850-1880 and 1960-1990 2:15 PM ME WILLIAM DUPOR, University of Pennsylvania Investment and Interest Rate Policy 3:00 PM DAE ROBERT MARGO and JEREMY ATACK, Vanderbilt University and NBER Rising Wage Dispersion in American Manufacturing, 1860-1880 ____________________________________________________________________________ -

Anna Mikusheva Recipient of the 2012 Elaine Bennett Research Prize

ANNA MIKUSHEVA RECIPIENT OF THE 2012 ELAINE BENNETT RESEARCH PRIZE Anna Mikusheva, the Castle-Krob Associate Professor of Economics at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, is the recipient of the 2012 Elaine Bennett Research Prize. The Elaine Bennett Research Prize was established in 1998 to recognize and honor outstanding research in any field of economics by a woman at the beginning of her career. Initially, her prize will be recognized at annual business luncheon of the American Economic Association Committee on the Status of Women in the Economics Profession (CSWEP) at the 2013 American Economic Association meetings in San Diego; Professor Mikusheva will formally accept the Prize at the 2014 meetings in Philadelphia. Professor Mikusheva is recognized for her important contributions to econometric theory. Her research, which combines a powerful command of econometric theory with a keen interest in developing tools that will be useful for tackling problems in applied econometric practice, has advanced econometric inference in two important areas. The first provides solutions to the challenging problem of forming accurate confidence intervals for a broad class of time series models used in applied macroeconomic research, in which data are generated by a stochastic process with persistent (unit root) shocks. Her second body of work, addressing inference in weakly-identified models, has provided new tools for hypothesis testing in this increasingly-important class of econometric models. She has applied these to analyze parameter estimates from dynamic stochastic general equilibrium (DSGE) models, which are widely used to design and evaluate macroeconomic policy. Professor Mikusheva holds a PhD in Economics from Harvard University and a PhD in Probability and Statistics from Moscow State University. -

Fiona M. Scott Morton

Fiona M. Scott Morton School of Management +1.203.432.5569 voice Yale University +1.203.432.6974 fax P.O. Box 208200 [email protected] New Haven, CT 06520-8200 Employment and Affiliations: 2014 – present Theodore Nierenberg Professor of Economics, Yale School of Management 2008 - present Visiting Professor, University of Edinburgh Economics Department 2013 - present Senior Consultant, Charles River Associates 2002 - 2014 Professor of Economics, Yale School of Management May 2011 – Deputy Assistant Attorney General for Economic Analysis, Antitrust Division, US December 2012 Department of Justice 2006 - 2011 Senior Consultant, Charles River Associates 2006 - 2010 Senior Associate Dean for Faculty Development, Yale School of Management 2005 - 2006 Adam Smith Visiting Fellow, Department of Economics, University of Edinburgh, Scotland 2000 - 2002 James L. Frank ’32 Associate Professor of Private Enterprise and Management, Yale School of Management 1999 - 2000 Associate Professor of Economics and Strategy, Yale School of Management 1997 - 1999 Assistant Professor of Economics and Strategy, Graduate School of Business, University of Chicago 1994 - 1997 Assistant Professor of Strategic Management, Graduate School of Business, Stanford University 1991 - 1992 Instructor for Economics 10, Profs. Martin Feldstein and Doug Elmendorf, Harvard University Education: 1994 Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Ph.D. Economics (advisors: Jerry Hausman and Nancy Rose) 1989 Yale University, B.A. Economics, magna cum laude Scholarly Publications: Berry, Steven, Martin Gaynor, and Fiona Scott Morton (forthcoming) “Do Increasing Markups Matter? Lessons from Empirical Industrial Organization” The Journal of Economic Perspectives. Federico, Giulio, Fiona Scott Morton and Carl Shapiro (2019) “Antitrust and Innovation: Welcoming and Protecting Disruption.” In Innovation Policy and the Economy, edited by Josh Lerner and Scott Stern. -

Executive Committee Meeting of April 12, 2013

Minutes of the Meeting of the Executive Committee in Chicago, IL, April 12, 2013 The first meeting of the 2013 Executive Committee was called to order at 10:00 AM on April 12, 2013 in the Malpensa Room of the Hyatt Regency O’Hare Hotel, Chicago, IL. Members present were: Orley Ashenfelter, Alan Auerbach, Janet Currie, Esther Duflo, Raquel Fernandez, Amy Finkelstein, Pinelopi Goldberg, Claudia Goldin, Anil Kashyap, Jonathan Levin, Rosa Matzkin, Paul Milgrom, William Nordhaus, Monika Piazzesi, Andrew Postlewaite, Peter Rousseau, and Christopher Sims. Judith Chevalier, David Laibson, and Jonathan Skinner participated in part of the meeting and Vincent Crawford participated by phone as members of the Honors and Awards Committee. Robert Hall participated in part of the meeting as chair of the Nominating Committee. Steven Durlauf attended the meeting as a guest. Assistant Secretary-Treasurer John Siegfried and General Counsel Terry Calvani also attended. Goldin welcomed the newly elected members of the 2013 Executive Committee: William Nordhaus, President-elect, Raquel Fernandez and Paul Milgrom, Vice-presidents; and Amy Finkelstein and Jonathan Levin. She also welcomed Steven Durlauf, Editor-Designate for the Journal of Economic Literature. The minutes of the January 3, 2013 meeting of the Executive Committee were approved as written. Increasing the Frequency of AER Publication (Goldberg). Goldberg reported on the feasibility of increasing the frequency of the AER to 11 monthly issues plus the May Papers and Proceedings starting in 2014. A higher frequency would reduce backlog, improve readability, and allow for the possibility of expanding the journal. Goldberg noted that the Budget and Finance Committee and the Standing Committee on Oversight of Operations and Publications had reviewed the report and approved of the increase and the additional resources that it would require. -

Biographies (169.16

PARTICIPANT BIOGRAPHIES Charles Angelucci Charles Angelucci is an Assistant Professor at Columbia Business School. He received his Ph.D. from the Toulouse School of Economics and focuses on microeconomic theory, organizational economics, and industrial organization. He is particularly interested in how organizations design decision rules and processes to foster information acquisition. He also conducts research on the media industry, which aims at understanding how the reliance on advertising revenues shapes newspapers’ pricing policies. Prior to joining Columbia, Charles was a Fellow at Harvard University in the Department of Economics. He also held a position at INSEAD where he taught Contract Theory. Guy Arie Guy Arie is an Assistant Professor at Simon Business School at the University of Rochester. His research interests include the study of employee incentives, strategic competition between firms, and the design of employee roles in firms. His current research focuses on the internal design of firms and employee incentives when the employee’s task becomes harder with effort. His new research is motivated by firm earning-report manipulations, insurer-hospital negotiations and sport leagues’ broadcast networks. Prior to pursuing his Ph.D., Arie worked as an R&D engineer and manager in large defense and communication firms. He received his Ph.D. from the Kellogg School of Business at Northwestern University. Orley Ashenfelter Orley Ashenfelter is the Joseph Douglas Green 1895 Professor of Economics at Princeton University. His areas of specialization include labor economics, econometrics, and law and economics. His current research includes the cross-country measurement of wage rates and many other issues related to the economics of labor markets. -

Anil Kashyap

February 2021 Anil K Kashyap University of Chicago Booth School of Business 5807 South Woodlawn Avenue Chicago, IL 60637 Phone: (773) 702-7260 e-mail: [email protected] Web:http://faculty.chicagobooth.edu/anil.kashyap Assistant: Mary Lagdameo, (773) 702-6324 Education Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Ph.D., 1989 University of California at Davis, B.A., 1982, Graduation with Highest Honors. Employment External Member, Financial Policy Committee, Bank of England, October 2016 – present. University of Chicago, Booth School of Business, Stevens Distinguished Professor of Economics and Finance, August 2019 – present. University of Chicago, Booth School of Business, Edward Eagle Brown Professor of Economics and Finance, August 2003 – July 2019. University of Chicago, Graduate School of Business, Professor of Economics, July 1996 – July 2003. University of Chicago, Graduate School of Business, Associate Professor of Business Economics, July 1993 – June 1996. University of Chicago, Graduate School of Business, Assistant Professor of Business Economics, July 1991 – June 1993. Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, Economist, August 1988 – June 1991. Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, Research Assistant, August 1982 – August 1984. Other Current Affiliations Consultant, Research Department, Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago, 1991 – present. Member, University of Chicago Center for East Asian Studies, 1995 – present. 1 Board of Associate Editors, Journal of Japanese and International Economics, 1996 – present. Research Associate, National Bureau of Economic Research, 1997 – present. (Faculty Research Fellow from 1992 -- 1996). Board of Editors, Japan and the World Economy, 2006 – present. Executive Board, Chicago Booth Initiative on Global Markets, 2006-present. (Co-Director, 2006-2013, 2019-present). -

Curriculum Vitae Judith A

Curriculum Vitae Judith A. Chevalier Home: Office: 236 Edwards St. School of Management New Haven, CT 06511 Yale University (203) 787-6518 165 Whitney Avenue New Haven, CT 06511 Email: [email protected] (203) 432-3122 Primary Positions: February 2005-present, William S. Beinecke Professor of Economics and Finance, Yale School of Management. September 2007-June 2009, Deputy Provost for Faculty Development, Yale University. June 2001- February 2005, Yale University School of Management, Professor of Finance and Economics. July 1999-May 2001, University of Chicago, Graduate School of Business, Professor of Economics. July 1997-June 1999, University of Chicago, Graduate School of Business, Associate Professor of Economics. July 1994-June 1997, University of Chicago, Graduate School of Business, Assistant Professor of Economics. July 1993 - June 1994, Harvard University, Department of Economics, Assistant Professor of Economics. Education: May, 1993, Ph.D., Economics, Massachusetts Institute of Technology. May, 1989, B.A., summa cum laude, Yale University, Distinction in the Major, Economics. Honors and Awards: Elected Fellow, Econometric Society, 2013. National Science Foundation research grant for 2011-2014, SBR 1128322, “Strategic Shoppers.” William F. O’Dell Award, Journal of Marketing Research, 2011. For paper published in the Journal of Marketing Research, August 2006. Elected member, American Academy of Arts and Sciences, 2006-present. Nominated paper, Smith Breeden prize, Journal of Finance, 1999. For paper published in the Journal of Finance, June 1999. Recipient, first annual Elaine Bennett Research Prize. This prize is intended to recognize research by a young woman in any area of economics. The prize is administered by the American Economic Association Committee on the Status of Women in the Economics Profession. -

Amy N. Finkelstein Recipient of the 2008 Elaine Bennett Research Prize

AMY N. FINKELSTEIN RECIPIENT OF THE 2008 ELAINE BENNETT RESEARCH PRIZE Amy N. Finkelstein is the 2008 recipient of the Elaine Bennett Research Prize. This prize will be given to her at the annual business meeting of the American Economics Association’s Committee on the Status of Women in the Economics Profession (CSWEP) on Saturday, January 3, 2009, from 5:00-6:00 pm in the Golden Gate 4 Room of the Hilton San Francisco Hotel. A reception will follow in the Golden Gate 5 Room to honor Professor Finkelstein and the winner of the 2008 Carolyn Shaw Bell award. It is not necessary to register for the AEA/ASSA meetings to attend these two events. Professor Finkelstein, a Professor of Economics at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, works at the intersection of public economics and health economics. She has found creative ways to identify the impact of changes in health care policy, such as the introduction of Medicare, the variation in tax subsidies for health insurance purchase, and the reform of federal liability rules relating to the vaccine industry, on health insurance and the utilization of medical services. Her path-breaking empirical work will influence the policy debate on the design of public interventions in health insurance markets in both the near term and over longer horizons. Professor Finkelstein received her Ph.D. from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in 2001 and is a Research Associate and Co-Director of the Public Economics Program at the National Bureau of Economic Research. Prior to joining the MIT faculty she was a Junior Fellow at the Harvard Society of Fellows (2002 – 2005). -

Emi Nakamura

Published three times annually by the American Economic Association’s Committee on the Status of Women news in the Economics Profession. 2015 ISSUE II IN THISCSWEP ISSUE An Interview with Serena Ng Feature Section Emi Nakamura Ethical Issues in Economics Research I Emi Nakamura, Associate Professor of Introduction by Amalia Miller and Business and Economics at Columbia Ragan Petrie . 3 University, is the recipient of the 2014 Conflicts of Interest and Ethical Elaine Bennett Research Prize. Estab- Research Standards at the AEA lished in 1998, the Elaine Bennett Re- Journals by Pinelopi Koujianou Goldberg . 3 search Prize recognizes and honors outstanding research in any field of Ethical Issues in Grant Review economics by a woman not more than by Nancy Lutz.. 5 seven years beyond her PhD. Professor Ethical Issues in Economics Research: Nakamura is recognized for her signifi- The Journal of Political Economy cant contributions to macroeconomics by Harald Uhlig . 7 and related fields. Her research, which Do’s and Don’ts of the Publication combines a powerful command of the- Process by Daron Acemoglu . 8 ory with detailed analyses of micro-level data has made important contributions From the CSWEP Chair to the study of price rigidity, measures of disaster risks and of long-run risks, Chair’s Letter Can you tell us something about growing by Marjorie B. McElroy . 2 exchange rate pass-through, fiscal mul- up in an academic family of economists? tipliers, and monetary non-neutrality. My parents love their work and really Tributes & Commendations In 2011, Dr. Nakamura received an wanted to give me a sense of what they NSF Career Award.