Capacious: Journal for Emerging Afect Inquiry Vol

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Culture of Recording: Christopher Raeburn and the Decca Record Company

A Culture of Recording: Christopher Raeburn and the Decca Record Company Sally Elizabeth Drew A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Sheffield Faculty of Arts and Humanities Department of Music This work was supported by the Arts & Humanities Research Council September 2018 1 2 Abstract This thesis examines the working culture of the Decca Record Company, and how group interaction and individual agency have made an impact on the production of music recordings. Founded in London in 1929, Decca built a global reputation as a pioneer of sound recording with access to the world’s leading musicians. With its roots in manufacturing and experimental wartime engineering, the company developed a peerless classical music catalogue that showcased technological innovation alongside artistic accomplishment. This investigation focuses specifically on the contribution of the recording producer at Decca in creating this legacy, as can be illustrated by the career of Christopher Raeburn, the company’s most prolific producer and specialist in opera and vocal repertoire. It is the first study to examine Raeburn’s archive, and is supported with unpublished memoirs, private papers and recorded interviews with colleagues, collaborators and artists. Using these sources, the thesis considers the history and functions of the staff producer within Decca’s wider operational structure in parallel with the personal aspirations of the individual in exerting control, choice and authority on the process and product of recording. Having been recruited to Decca by John Culshaw in 1957, Raeburn’s fifty-year career spanned seminal moments of the company’s artistic and commercial lifecycle: from assisting in exploiting the dramatic potential of stereo technology in Culshaw’s Ring during the 1960s to his serving as audio producer for the 1990 The Three Tenors Concert international phenomenon. -

Antarctica: Music, Sounds and Cultural Connections

Antarctica Music, sounds and cultural connections Antarctica Music, sounds and cultural connections Edited by Bernadette Hince, Rupert Summerson and Arnan Wiesel Published by ANU Press The Australian National University Acton ACT 2601, Australia Email: [email protected] This title is also available online at http://press.anu.edu.au National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Title: Antarctica - music, sounds and cultural connections / edited by Bernadette Hince, Rupert Summerson, Arnan Wiesel. ISBN: 9781925022285 (paperback) 9781925022292 (ebook) Subjects: Australasian Antarctic Expedition (1911-1914)--Centennial celebrations, etc. Music festivals--Australian Capital Territory--Canberra. Antarctica--Discovery and exploration--Australian--Congresses. Antarctica--Songs and music--Congresses. Other Creators/Contributors: Hince, B. (Bernadette), editor. Summerson, Rupert, editor. Wiesel, Arnan, editor. Australian National University School of Music. Antarctica - music, sounds and cultural connections (2011 : Australian National University). Dewey Number: 780.789471 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Cover design and layout by ANU Press Cover photo: Moonrise over Fram Bank, Antarctica. Photographer: Steve Nicol © Printed by Griffin Press This edition © 2015 ANU Press Contents Preface: Music and Antarctica . ix Arnan Wiesel Introduction: Listening to Antarctica . 1 Tom Griffiths Mawson’s musings and Morse code: Antarctic silence at the end of the ‘Heroic Era’, and how it was lost . 15 Mark Pharaoh Thulia: a Tale of the Antarctic (1843): The earliest Antarctic poem and its musical setting . 23 Elizabeth Truswell Nankyoku no kyoku: The cultural life of the Shirase Antarctic Expedition 1910–12 . -

Heroes (TV Series) - Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia Pagina 1 Di 20

Heroes (TV series) - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Pagina 1 di 20 Heroes (TV series) From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Heroes was an American science fiction Heroes television drama series created by Tim Kring that appeared on NBC for four seasons from September 25, 2006 through February 8, 2010. The series tells the stories of ordinary people who discover superhuman abilities, and how these abilities take effect in the characters' lives. The The logo for the series featuring a solar eclipse series emulates the aesthetic style and storytelling Genre Serial drama of American comic books, using short, multi- Science fiction episode story arcs that build upon a larger, more encompassing arc. [1] The series is produced by Created by Tim Kring Tailwind Productions in association with Starring David Anders Universal Media Studios,[2] and was filmed Kristen Bell primarily in Los Angeles, California. [3] Santiago Cabrera Four complete seasons aired, ending on February Jack Coleman 8, 2010. The critically acclaimed first season had Tawny Cypress a run of 23 episodes and garnered an average of Dana Davis 14.3 million viewers in the United States, Noah Gray-Cabey receiving the highest rating for an NBC drama Greg Grunberg premiere in five years. [4] The second season of Robert Knepper Heroes attracted an average of 13.1 million Ali Larter viewers in the U.S., [5] and marked NBC's sole series among the top 20 ranked programs in total James Kyson Lee viewership for the 2007–2008 season. [6] Heroes Masi Oka has garnered a number of awards and Hayden Panettiere nominations, including Primetime Emmy awards, Adrian Pasdar Golden Globes, People's Choice Awards and Zachary Quinto [2] British Academy Television Awards. -

Ways to Become a Digital Nomad

23 WAYS TO BECOME A DIGITAL NOMAD We give ideas, so you can’t give excuses…. NATHAN BUCHAN & HANNAH MARTIN (WORLD NATE & INTREPID INTROVERT) DESIGN & SELL CLOTHING 1 WITH TEESPRING Info: Design and create your own tees, hoodies, mugs, & more with $0 investment! All you need to do is design your logo or upload an existing logo you have already created. Place it on a product of your choice (such as a long sleeve shirt). Choose the type of material you wish to use. Then name the price you wish to sell it for. TeeSpring will tell you the cost of each item made. You will reap the profit from each item you sell. Here’s the cool thing: It doesn’t cost you anything. TeeSpring won’t make your shirt until AFTER someone has purchased; therefore no risk of investment is made. The company will then make and ship each order out for you. You do nothing but advertise your products and reap the rewards of your sales. Income Potential: Scalable with marketing.. You can run Facebook campaigns from within TeeSpring. We have tutorials on this in our Behind Closed Doors Membership here SELL ON EBAY: BUY 2 ON AMAZON Info: Source a product on Amazon and list the same item on E-bay with a markup. Then once it’s sold on E-Bay, buy that same product on Amazon and send it directly to your customer. * Just make sure there is a decent amount of stock and not just one or two left. Begin by researching which products are trending and how much competition you have with selling it on E-bay. -

Three Heroes Free

FREE THREE HEROES PDF Jo Beverley | 672 pages | 01 Jun 2004 | Penguin Putnam Inc | 9780451212009 | English | New York, United States Church of the Three Heroes - Villains Wiki - villains, bad guys, comic books, anime Volume Three begins with the assassination attempt on Nathan, and the consequences it Three Heroes in the future. In addition, several villains escape from the confines of Level 5, and the Company attempts to recapture them. Volume Four starts with Nathan telling the President about the existence of advanced humans and the hunt for said humans Three Heroes. The third volume of Heroesentitled Villainsaired for thirteen episodes. Nathan is visited in the hospital by a Three Heroes face. Hiro receives a massage from his father and meets a "speedster". Claire is visited by Sylar. Matt is sent against his will to a distant location. Mohinder learns something amazing because of Maya. Hiro sees his death by an unlikely person. Tracy's power is revealed. Angela takes control of the Company. Mohinder experiences the said effects of his new found abilities. Meredith returns to protect Claire. Tracy tries to find answers about Nikiwhich leads her to Micah. Hiro loses the second half of an important formula to Daphne. Claire asks Meredith to teach her how to fight. Peter travels to the futurewhere he gains a dangerous new Three Heroes. Matt has visions of Three Heroes same future, seeing a woman that he will one day have a child with. Hiro and Andolooking for answers, free Adam Monroe from his grave. Original Air Date: 13 Three Heroes Nathan learns a secret from his past, that tries Three Heroes even closer to Tracy. -

Reel-To-Real: Intimate Audio Epistolarity During the Vietnam War Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requireme

Reel-to-Real: Intimate Audio Epistolarity During the Vietnam War Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Matthew Alan Campbell, B.A. Graduate Program in Music The Ohio State University 2019 Dissertation Committee Ryan T. Skinner, Advisor Danielle Fosler-Lussier Barry Shank 1 Copyrighted by Matthew Alan Campbell 2019 2 Abstract For members of the United States Armed Forces, communicating with one’s loved ones has taken many forms, employing every available medium from the telegraph to Twitter. My project examines one particular mode of exchange—“audio letters”—during one of the US military’s most trying and traumatic periods, the Vietnam War. By making possible the transmission of the embodied voice, experiential soundscapes, and personalized popular culture to zones generally restricted to purely written or typed correspondence, these recordings enabled forms of romantic, platonic, and familial intimacy beyond that of the written word. More specifically, I will examine the impact of war and its sustained separations on the creative and improvisational use of prosthetic culture, technologies that allow human beings to extend and manipulate aspects of their person beyond their own bodies. Reel-to-reel was part of a constellation of amateur recording technologies, including Super 8mm film, Polaroid photography, and the Kodak slide carousel, which, for the first time, allowed average Americans the ability to capture, reify, and share their life experiences in multiple modalities, resulting in the construction of a set of media-inflected subjectivities (at home) and intimate intersubjectivities developed across spatiotemporal divides. -

Spreadshirt: My Newest Passive Income Stream and How You Can Earn Too

Episode 7: Spreadshirt: My Newest Passive Income Stream and How You Can Earn Too Subscribe to the podcast here. Hey what’s up everybody! Welcome to numero siete of my podcast, number 7. I’m kind of pumped about this podcast because I hope it’s going to give some of you another way or possible way to monetize your website. I just got my first check from SpreadShirt and it was 530 bucks and 20 cents, to be exact. And you can go to 2createawebsite.com/podcast7 to see a screenshot of the earnings. I do that to show proof. I don’t do that to brag. I know there’s a lot of sites out here that talk about making money and they never show that they are. So I do that from time to time for that very reason but not to show off. Oh and while you’re there, you gotta check out my new site design. Yaaaay! My site got a little facelift about a week ago so you gotta check it out. SpreadShirt is a print on demand affiliate program where you simply upload an image, and then you can put that image on a shirt, a button, a hat or whatever. Then you mark up the price to whatever you want to sell it for, and your markup is your commission. So if the base price of the shirt is $10 and you sell it for $20, then you get $10 for every shirt sold. It’s completely free. Now there are premium options and I’m going to talk about this later in the podcast, but it doesn’t cost you anything. -

Econ Board Wants More Info

1A WEEKEND EDITION FRIDAY & SATURDAY, OCTOBER 12 & 13, 2012 | YOUR COMMUNITY NEWSPAPER SINCE 1874 | 75¢ Lake City Reporter LAKECITYREPORTER.COM EVENTS CENTER ‘A lot of pink’ PROPOSAL Econ Oct. 12 board Classic car parade On Friday, Oct. 12 from 6 to 9 p.m. American wants Hometown Veteran Assist Inc. will host a cruise in and classic car parade at Hardees on U.S. 90. All of more the proceeds benefit local veterans. Oct. 13 info Monument rededication Please join the Sons of Possible Ellisville Confederate Veterans and location prompts the United Daughters of the Confederacy on questions. Saturday, Oct. 13 at 11 a.m. for the Rededication of the By TONY BRITT Confederate Monument, [email protected] which was originally dedi- cated 100 years ago. The Columbia County Economic Development Department board of direc- Zumba charity tors is Zumba to benefit local interested breast cancer awareness in the Oct. 13 from 5:30 to 7 p.m. at c o u n t y ’ s the Teen Town Recreation JASON MATTHEW WALKER/Lake City Reporter proposed Building, 533 NW Desoto Lake City resident Marcelle Bedenbaugh is in the market for a pink flamingo after attending the Standing up to Breast e v e n t s St. The Zumbathon Charity Cancer luncheon Thursday. ‘I’ve had breast cancer two times. I enjoyed the chemo the first time I said what the heck, c e n t e r , Event will benefit the I’ll do it again,’ Bedenbaugh joked. but wants Suwannee River Breast Quillen m o r e Cancer Awareness Assn. -

![Createworld 2011 Proceedings [PDF]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8165/createworld-2011-proceedings-pdf-1388165.webp)

Createworld 2011 Proceedings [PDF]

CreateWorld 2011 Proceedings CreateWorld11 Conference 28 November - 30 November 2011 Griffith University, Brisbane Queensland Australia Editors Michael Docherty :: Queensland University of Technology Matt Hitchcock :: Griffith University, Qld Conservatorium CreateWorld 2011 Proceedings of the CreateWorld11 Conference 20 - 30 November Griffith University, Brisbane Queensland Australia Editor Michael Docherty :: Queensland University of Technology Matt HItchcock :: Griffith University Web Content Editor Andrew Jeffrey http://www.auc.edu.au/Create+World+2011 ISBN: 978-0-947209-38-4 © Copyright 2011, Apple University Consortium Australia, and individual authors. Apart from any use as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part may be reproduced by any process without the written permission of the copyright holders. CreateWorld 2011 Proceedings of the CreateWorld11 Conference 28 - 30 November, 2011 Griffith University, Brisbane Queensland Australia Contents Robert Burrell, Queensland Conservatorium, Griffith University 1 Zoomusicology, Live Performance and DAW [email protected] Dean Chircop, Griffith Film School (Film and Screen Media Productions) 10 The Digital Cinematography Revolution & 35mm Sensors: Arriflex Alexa, Sony PMW-F3, Panasonic AF100, Sony HDCAM HDW-750 and the Cannon 5D DSLR. [email protected] Kim Cunio, Queensland Conservatorium Griffith University 18 ISHQ: A collaborative film and music project – art music and image as an installation, joint art as boundary crossing. [email protected]; Louise Harvey, -

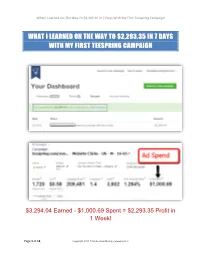

What I Learned on the Way to $2,293.35 in 7 Days with My First Teespring Campaign

What I Learned On The Way To $2,293.35 In 7 Days With My First Teespring Campaign WHAT I LEARNED ON THE WAY TO $2,,293..35 IN 7 DAYS WITH MY FIRST TEESPRING CAMPAIGN $3,294.04 Earned - $1,000.69 Spent = $2,293.35 Profit in 1 Week! Page 1 of 14 Copyright 2013 © Niche Gold Mining Company LLC What I Learned On The Way To $2,293.35 In 7 Days With My First Teespring Campaign All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without written permission from the author, except in the case of a reviewer, who may quote brief passages embodied in critical articles or in a review. Trademarked names appear throughout this book. Rather than use a trademark symbol with every occurrence of a trademarked name, names are used in an editorial fashion, with no intention of infringement of the respective owner’s trademark. The information in this book is distributed on an “as is” basis, without warranty. Although every precaution has been taken in the preparation of this work, neither the author nor the publisher shall have any liability to any person or entity with respect to any loss or damage caused or alleged to be caused directly or indirectly by the information contained in this book. Note: You will not receive videos as separate downloads. All videos may be watched or downloaded via links at the end of this book. CONTENTS What I Learned On The Way To $2,,293.35 In 7 Days With My First Teespring Campaign ............................................... -

Web Serial Toolbox

Web Serial Toolbox Why & How To Serialize Your Fiction Online (for almost no money) by Cecilia Tan ctan.writer @ gmail.com Twitter @ceciliatan #serialtoolbox What is a web serial? What is a web serial? Serialized storytelling is already the norm in ● What is a web serial? Serialized storytelling is already the norm in ● comic books What is a web serial? Serialized storytelling is already the norm in ● comic books ● television series What is a web serial? Serialized storytelling is already the norm in ● comic books ● television series ● web comics Charles Dickens (The Pickwick Papers) and Alexandre Dumas (Three Musketeers) used the emergent mass media of their era (broadsheet printing & early newspapers) to serialize to mass audiences. Now we have the Internet. What is a web serial? ● Text fiction telling a continuing story that is posted online What is a web serial? ● Text fiction telling a continuing story that is posted online – may or may not have a set length/ending ● closed serials are like a novel but split up ● open serials are like a soap opera What is a web serial? ● Text fiction telling a continuing story that is posted online – may or may not have a set length/ending ● closed serials are like a novel but split up ● open serials are like a soap opera – may or may not be posted free to read ● most are free to read on the web ● some are to subscribers only, or are “freemium” going first to subscribers and then free to read for all later Why write a web serial? Why write a web serial? Find readers as addicted to reading as you are to writing. -

Heroes and Philosophy

ftoc.indd viii 6/23/09 10:11:32 AM HEROES AND PHILOSOPHY ffirs.indd i 6/23/09 10:11:11 AM The Blackwell Philosophy and Pop Culture Series Series Editor: William Irwin South Park and Philosophy Edited by Robert Arp Metallica and Philosophy Edited by William Irwin Family Guy and Philosophy Edited by J. Jeremy Wisnewski The Daily Show and Philosophy Edited by Jason Holt Lost and Philosophy Edited by Sharon Kaye 24 and Philosophy Edited by Richard Davis, Jennifer Hart Week, and Ronald Weed Battlestar Galactica and Philosophy Edited by Jason T. Eberl The Offi ce and Philosophy Edited by J. Jeremy Wisnewski Batman and Philosophy Edited by Mark D. White and Robert Arp House and Philosophy Edited by Henry Jacoby Watchmen and Philosophy Edited by Mark D. White X-Men and Philosophy Edited by Rebecca Housel and J. Jeremy Wisnewski Terminator and Philosophy Edited by Richard Brown and Kevin Decker ffirs.indd ii 6/23/09 10:11:12 AM HEROES AND PHILOSOPHY BUY THE BOOK, SAVE THE WORLD Edited by David Kyle Johnson John Wiley & Sons, Inc. ffirs.indd iii 6/23/09 10:11:12 AM This book is printed on acid-free paper. Copyright © 2009 by John Wiley & Sons, Inc. All rights reserved Published by John Wiley & Sons, Inc., Hoboken, New Jersey Published simultaneously in Canada No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, scanning, or otherwise, except as permitted under Section 107 or 108 of the 1976 United States Copyright Act, without either the prior written permission of the Publisher, or autho- rization through payment of the appropriate per-copy fee to the Copyright Clearance Center, 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923, (978) 750–8400, fax (978) 646–8600, or on the web at www.copyright.com.