NYU Law Review

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Blacks and Asians in Mississippi Masala, Barriers to Coalition Building

Both Edges of the Margin: Blacks and Asians in Mississippi Masala, Barriers to Coalition Building Taunya Lovell Bankst Asians often take the middle position between White privilege and Black subordination and therefore participate in what Professor Banks calls "simultaneous racism," where one racially subordinatedgroup subordi- nates another. She observes that the experience of Asian Indian immi- grants in Mira Nair's film parallels a much earlier Chinese immigrant experience in Mississippi, indicatinga pattern of how the dominantpower uses law to enforce insularityamong and thereby control different groups in a pluralistic society. However, Banks argues that the mere existence of such legal constraintsdoes not excuse the behavior of White appeasement or group insularityamong both Asians and Blacks. Instead,she makes an appealfor engaging in the difficult task of coalition-buildingon political, economic, socialand personallevels among minority groups. "When races come together, as in the present age, it should not be merely the gathering of a crowd; there must be a bond of relation, or they will collide...." -Rabindranath Tagore1 "When spiders unite, they can tie up a lion." -Ethiopian proverb I. INTRODUCTION In the 1870s, White land owners recruited poor laborers from Sze Yap or the Four Counties districts in China to work on plantations in the Mis- sissippi Delta, marking the formal entry of Asians2 into Mississippi's black © 1998 Asian Law Journal, Inc. I Jacob A. France Professor of Equality Jurisprudence, University of Maryland School of Law. The author thanks Muriel Morisey, Maxwell Chibundu, and Frank Wu for their suggestions and comments on earlier drafts of this Article. 1. -

Chinatown and Urban Redevelopment: a Spatial Narrative of Race, Identity, and Urban Politics 1950 – 2000

CHINATOWN AND URBAN REDEVELOPMENT: A SPATIAL NARRATIVE OF RACE, IDENTITY, AND URBAN POLITICS 1950 – 2000 BY CHUO LI DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Landscape Architecture in the Graduate College of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 2011 Urbana, Illinois Doctoral Committee: Professor D. Fairchild Ruggles, Chair Professor Dianne Harris Associate Professor Martin Manalansan Associate Professor Faranak Miraftab Abstract The dissertation explores the intricate relations between landscape, race/ethnicity, and urban economy and politics in American Chinatowns. It focuses on the landscape changes and spatial struggles in the Chinatowns under the forces of urban redevelopment after WWII. As the world has entered into a global era in the second half of the twentieth century, the conditions of Chinatown have significantly changed due to the explosion of information and the blurring of racial and cultural boundaries. One major change has been the new agenda of urban land planning which increasingly prioritizes the rationality of capital accumulation. The different stages of urban redevelopment have in common the deliberate efforts to manipulate the land uses and spatial representations of Chinatown as part of the socio-cultural strategies of urban development. A central thread linking the dissertation’s chapters is the attempt to examine the contingent and often contradictory production and reproduction of socio-spatial forms in Chinatowns when the world is increasingly structured around the dynamics of economic and technological changes with the new forms of global and local activities. Late capitalism has dramatically altered city forms such that a new understanding of the role of ethnicity and race in the making of urban space is required. -

The Political Economy of Colorblindness: Neoliberalism and the Reproduction of Racial Inequality in the United States

THE POLITICAL ECONOMY OF COLORBLINDNESS: NEOLIBERALISM AND THE REPRODUCTION OF RACIAL INEQUALITY IN THE UNITED STATES A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at George Mason University By Phillip A. Hutchison Master of Arts University of California, Los Angeles, 2002 Director: Paul Smith, Professor Cultural Studies Fall Semester 2010 George Mason University Fairfax, VA Copyright: 2010 Phillip A. Hutchison All Rights Reserved ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Abstract ............................................................................................................................. iv Introduction ........................................................................................................................ 1 Literature Review............................................................................................................. 30 Chapter 1 .......................................................................................................................... 69 Chapter 2 .......................................................................................................................... 94 Chapter 3 ........................................................................................................................ 138 Chapter 4 ........................................................................................................................ 169 Chapter 5 ....................................................................................................................... -

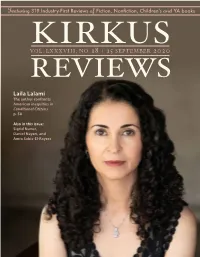

Kirkus Reviews on Our Website by Logging in As a Subscriber

Featuring 319 Industry-First Reviews of Fiction, Nonfiction, Children'sand YA books VOL.KIRKUS LXXXVIII, NO. 18 | 15 SEPTEMBER 2020 REVIEWS Laila Lalami The author confronts American inequities in Conditional Citizens p. 58 Also in this issue: Sigrid Nunez, Daniel Nayeri, and Amra Sabic-El-Rayess from the editor’s desk: The Way I Read Now Chairman BY TOM BEER HERBERT SIMON President & Publisher MARC WINKELMAN John Paraskevas # Among the many changes in my daily life this year—working from home, Chief Executive Officer wearing a mask in public, watching too much TV—my changing read- MEG LABORDE KUEHN ing habits register deeply. For one thing, I read on a Kindle now, with the [email protected] Editor-in-Chief exception of the rare galley sent to me at home and the books I’ve made TOM BEER a point of purchasing from local independent bookstores or ordering on [email protected] Vice President of Marketing Bookshop.org. The Kindle was borrowed—OK, confiscated—from my SARAH KALINA boyfriend at the beginning of the pandemic, when I left dozens of advance [email protected] reader copies behind at the office and accepted the reality that digital gal- Managing/Nonfiction Editor ERIC LIEBETRAU leys would be a practical necessity for the foreseeable future. I can’t say that I [email protected] love reading on my “new” Kindle—I’m still a sucker for physical books after Fiction Editor LAURIE MUCHNICK all these years—but I’ll admit that it fulfills its purpose efficiently. And I do [email protected] Tom Beer rather enjoy the instant gratification of going on NetGalley or Edelweiss Young Readers’ Editor VICKY SMITH and dispatching multiple books to my device in one fell swoop—a harmless [email protected] form of bingeing that affords a little dopamine rush. -

Righting the Wrongs of Slavery, 89 Geo. LJ 2531

UIC School of Law UIC Law Open Access Repository UIC Law Open Access Faculty Scholarship 1-1-2001 Forgive U.S. Our Debts? Righting the Wrongs of Slavery, 89 Geo. L.J. 2531 (2001) Kevin Hopkins John Marshall Law School Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.law.uic.edu/facpubs Part of the Law and Race Commons, and the Legal History Commons Recommended Citation Kevin Hopkins, Forgive U.S. Our Debts? Righting the Wrongs of Slavery, 89 Geo. L.J. 2531 (2001). https://repository.law.uic.edu/facpubs/153 This Book Review is brought to you for free and open access by UIC Law Open Access Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in UIC Law Open Access Faculty Scholarship by an authorized administrator of UIC Law Open Access Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. REVIEW ESSAY Forgive U.S. Our Debts? Righting the Wrongs of Slavery KEvIN HOPKINS* "We must make sure that their deaths have posthumous meaning. We must make sure that from now until the end of days all humankind stares this evil in the face.., and only then can we be sure it will never arise again." President Ronald Reagan' INTRODUCTION: Tm BIG PAYBACK In recent months, claims for reparations for slavery have gained new popular- ity amongst black intellectuals and trial lawyers and have been given additional momentum by the publication of Randall Robinson's controversial and thought- provoking book, The Debt: What America Owes to Blacks.2 In The Debt, Robinson makes a serious and persuasive case for the payment of reparations by the United States government to African-Americans for both the injustices done to their ancestors during slavery and the effect of those wrongs on the current * Associate Professor of Law, The John Marshall Law School. -

The Archaeological Importance of the Black Towns in the American West and Late-Nineteenth Century Constructions of Blackness

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 2012 I'm Really Just an American: The Archaeological Importance of the Black Towns in the American West and Late-Nineteenth Century Constructions of Blackness Shea Aisha Winsett College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the African American Studies Commons, African History Commons, History of Art, Architecture, and Archaeology Commons, and the Social and Cultural Anthropology Commons Recommended Citation Winsett, Shea Aisha, "I'm Really Just an American: The Archaeological Importance of the Black Towns in the American West and Late-Nineteenth Century Constructions of Blackness" (2012). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539626687. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-tesy-ns27 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. I’m Really Just An American: The Archaeological Importance of the Black Towns in the American West and Late-Nineteenth Century Constructions of Blackness Shea Aisha Winsett Hyattsville, Maryland Bachelors of Arts, Oberlin College, 2008 A Thesis presented to the Graduate Faculty of the College of William and Mary in Candidacy for the Degree of Master of Arts Department -

Geschichte Neuerwerbungsliste 1. Quartal 2002

Geschichte Neuerwerbungsliste 1. Quartal 2002 Geschichte: Einführungen ....................................................................................................................................... 2 Geschichtsschreibung und Geschichtstheorie.......................................................................................................... 2 Teilbereiche der Geschichte (Politische Geschichte, Kultur-, Sozial- und Wirtschaftsgeschichte allgemein)........ 4 Historische Hilfswissenschaften.............................................................................................................................. 7 Ur- und Frühgeschichte, Mittelalter- und Neuzeitarchäologie ................................................................................ 9 Allgemeine Weltgeschichte, Geschichte der Entdeckungen, Geschichte der Weltkriege ..................................... 15 Alte Geschichte ..................................................................................................................................................... 23 Europäische Geschichte in Mittelalter und Neuzeit .............................................................................................. 25 Deutsche Geschichte ............................................................................................................................................. 30 Geschichte der deutschen Laender und Staedte..................................................................................................... 37 Geschichte der Schweiz, Österreichs, -

“Just Ask Mi 'Bout Brooklyn:” West Indian Identities, Transgeographies, and Livin

“JUST ASK MI ’BOUT BROOKLYN:” WEST INDIAN IDENTITIES, TRANSGEOGRAPHIES, AND LIVING REGGAE CULTURE A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Cornell University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Sabia McCoy-Torres August 2015 © 2015 Sabia McCoy-Torres “JUST ASK MI ’BOUT BROOKLYN:” WEST INDIAN IDENTITIES, TRANSGEOGRAPHIES, AND LIVING REGGAE CULTURE Sabia McCoy-Torres, Ph.D. Cornell University 2015 This ethnography explores the symbiotic relationship between the West Indian Diaspora and performance based, Jamaican originated, reggae culture. The field site was Brooklyn, New York. I analyze the intersections of reggae with racial and cultural identity construction, expressions of gender and sexuality, transnationalism, and place making practices. The formation of a local, West Indian led, reggae related economy is also a subject of focus. In order to theorize the impact West Indians have on Brooklyn and their subjectivities, I develop the concepts transgeographies and figurative citizenship. I argue that the West Indian Diaspora creates transgeographic cultural places that specific sociocultural practices and performance help to form. I offer that performance, action, and material alteration coalesce to physically transform space and imbue it with affect and sensory elements that together constitute links to the various nations of the Caribbean. The West Indian geographies of Brooklyn are thereby brought inside the Caribbean space expanding how geography is conceived of as an analytic. Emergent diasporic subjectivities are formed within these transgeographic cultural places, one of them being what I term figurative citizenship. This work also includes analyses of the relationship of West Indians to U.S. -

Lebanese-Americans Identity, Citizenship and Political Behavior

NOTRE DAME UNIVERSITY – LOUAIZE PALMA JOURNAL A MULTIDISCIPLINARY RESEARCH PUBLICATION Volume 11 Issue 1 2009 Contents Editorial 3 New century, old story! Race, religion, bureaucrats, and the Australian Lebanese story 7 Anne Monsour The Transnational Imagination: XXth century networks and institutions of the Mashreqi migration to Mexico 31 Camila Pastor de Maria y Campos Balad Niswen – Hukum Niswen: The Perception of Gender Inversions Between Lebanon and Australia 73 Nelia Hyndman-Rizik Diaspora and e-Commerce: The Globalization of Lebanese Baklava 105 Guita Hourani Lebanese-Americans’ Identity, Citizenship and Political Behavior 139 Rita Stephan Pathways to Social Mobility Lebanese Immigrants in Detroit and Small Business Enterprise 163 Sawsan Abdulrahim Pal. Jour., 2009, 11,3:5 Copyright © 2009 by Palma Journal, All Rights Reserved Editorial Palma Journal’s special issue on migration aims at contributing to this area of study in a unique manner. By providing a forum for non-veteran scholars in the field to share their current research findings with a broader public, Palma has joined hands with the Lebanese Emigration Research Center in celebrating LERC’s sixth anniversary serving international and interdisciplinary scholarly discourse between Lebanon and the rest of the world. The migration special issue owes its inception to a conversation between Beirut und Buenos Aires, in which Eugene Sensenig-Dabbous, an Austrian- American researcher at LERC, and the eminent Argentinean migration scholar, Ignacio Klich, developed the idea for a special migration issue and presented it to the LERC research team. This Libano-Austro-Iberian link laid the foundation for an exciting collection of articles, which I have had the privilege to guest edit. -

From Freedom to Bondage: the Jamaican Maroons, 1655-1770

From Freedom to Bondage: The Jamaican Maroons, 1655-1770 Jonathan Brooks, University of North Carolina Wilmington Andrew Clark, Faculty Mentor, UNCW Abstract: The Jamaican Maroons were not a small rebel community, instead they were a complex polity that operated as such from 1655-1770. They created a favorable trade balance with Jamaica and the British. They created a network of villages that supported the growth of their collective identity through borrowed culture from Africa and Europe and through created culture unique to Maroons. They were self-sufficient and practiced sustainable agricultural practices. The British recognized the Maroons as a threat to their possession of Jamaica and embarked on multiple campaigns against the Maroons, utilizing both external military force, in the form of Jamaican mercenaries, and internal force in the form of British and Jamaican military regiments. Through a systematic breakdown of the power structure of the Maroons, the British were able to subject them through treaty. By addressing the nature of Maroon society and growth of the Maroon state, their agency can be recognized as a dominating factor in Jamaican politics and development of the country. In 1509 the Spanish settled Jamaica and brought with them the institution of slavery. By 1655, when the British invaded the island, there were 558 slaves.1 During the battle most slaves were separated from their masters and fled to the mountains. Two major factions of Maroons established themselves on opposite ends of the island, the Windward and Leeward Maroons. These two groups formed the first independent polities from European colonial rule. The two groups formed independent from each other and with very different political structures but similar economic and social structures. -

FACING the CHANGE CANADA and the INTERNATIONAL DECADE for PEOPLE of AFRICAN DESCENT Special Edition in Partnership with the Canadian Commission for UNESCO

PART 1 FACING THE CHANGE CANADA AND THE INTERNATIONAL DECADE FOR PEOPLE OF AFRICAN DESCENT Special Edition in Partnership with the Canadian Commission for UNESCO VOLUME 16 | NO. 3 | 2019 YEMAYA Komi Olaf SANKOFA EAGLE CLAN Komi Olaf PART ONE “Not everything that is faced can be changed, but nothing can be changed until it is faced” – James Baldwin INTRODUCTION FACING THE FINDINGS Towards Recognition, Justice and Development People of African Descent in Canada: 3 Mireille Apollon 32 A Diversity of Origins and Identities Jean-Pierre Corbeil and Hélène Maheux Overview of the Issue 5 Miriam Taylor Inflection Point – Assessing Progress on Racial Health Inequities in Canada During the Decade for 36 People of African Descent FACING THE CHALLENGES AND OPPORTUNITIES Tari Ajadi OF THE INTERNATIONAL DECADE What the African American Diaspora can Teach Us A Decade to Eradicate Discrimination and the 39 about Vernacular Black English Scourge of Racism: National Black Canadians Dr. Shana Poplack 9 Summits Take on the Legacy of Slavery The Right Honourable Michaëlle Jean THE FACE OF LIVED EXPERIENCE Unique Opportunities and Responsibilities 13 of the International Decade The Black Experience in the Greater Toronto Area The Honourable Dr. Jean Augustine 46 Dr. Wendy Cukier, Dr Mohamed Elmi and Erica Wright Count Us In: Nova Scotia’s Action Plan in Response Challenging Racism Through Asset Mapping and to the International Decade for People of African Case Study Approaches: An Example from the 16 Descent, 2015-2024 49 African Descent Communities in Vancouver, BC Wayn Hamilton Rebecca Aiyesa and Dr. Oleksander (Sasha) Kondrashov Migration, Identity and Oppression: An Inter-provincial Community Initiative Exploring FACING THE LEGACY OF COLONIALISM and Addressing the Intersectionality of Oppression and Related Health, Social and Economic Costs The Sun Never Sets, The Sun Waits to Rise: 53 The Enduring Structural Legacies of European Dr. -

Lebanese Families Who Arrived in South Carolina Before 1950 Elizabeth Whitaker Clemson University, [email protected]

Clemson University TigerPrints All Theses Theses 12-2006 From the Social Margins to the Center: Lebanese Families Who Arrived in South Carolina before 1950 Elizabeth Whitaker Clemson University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/all_theses Part of the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Whitaker, Elizabeth, "From the Social Margins to the Center: Lebanese Families Who Arrived in South Carolina before 1950" (2006). All Theses. 6. https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/all_theses/6 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses at TigerPrints. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Theses by an authorized administrator of TigerPrints. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FROM THE SOCIAL MARGINS TO THE CENTER LEBANESE FAMILIES WHO ARRIVED IN SOUTH CAROLINA BEFORE 1950 A Thesis Presented to the Graduate School of Clemson University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts History by Elizabeth Virginia Whitaker December 2006 Accepted by: Megan Taylor Shockley, Committee Chair Alan Grubb J.R. Andrew ii ABSTRACT The Lebanese families who arrived in South Carolina found themselves in a different environment than most had anticipated. Those who had spent time elsewhere in the U.S. found predominantly rural and predominantly Protestant South Carolina to be almost as alien as they or their parents had found the United States due partly to the religious differences and partly to the cultural differences between the Northeast, where most of them had lived for at least a few years after arriving in the United States, and the Southeast.