Sagittal a Microtonal Notation System by George D

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The 17-Tone Puzzle — and the Neo-Medieval Key That Unlocks It

The 17-tone Puzzle — And the Neo-medieval Key That Unlocks It by George Secor A Grave Misunderstanding The 17 division of the octave has to be one of the most misunderstood alternative tuning systems available to the microtonal experimenter. In comparison with divisions such as 19, 22, and 31, it has two major advantages: not only are its fifths better in tune, but it is also more manageable, considering its very reasonable number of tones per octave. A third advantage becomes apparent immediately upon hearing diatonic melodies played in it, one note at a time: 17 is wonderful for melody, outshining both the twelve-tone equal temperament (12-ET) and the Pythagorean tuning in this respect. The most serious problem becomes apparent when we discover that diatonic harmony in this system sounds highly dissonant, considerably more so than is the case with either 12-ET or the Pythagorean tuning, on which we were hoping to improve. Without any further thought, most experimenters thus consign the 17-tone system to the discard pile, confident in the knowledge that there are, after all, much better alternatives available. My own thinking about 17 started in exactly this way. In 1976, having been a microtonal experimenter for thirteen years, I went on record, dismissing 17-ET in only a couple of sentences: The 17-tone equal temperament is of questionable harmonic utility. If you try it, I doubt you’ll stay with it for long.1 Since that time I have become aware of some things which have caused me to change my opinion completely. -

Download the Just Intonation Primer

THE JUST INTONATION PPRIRIMMEERR An introduction to the theory and practice of Just Intonation by David B. Doty Uncommon Practice — a CD of original music in Just Intonation by David B. Doty This CD contains seven compositions in Just Intonation in diverse styles — ranging from short “fractured pop tunes” to extended orchestral movements — realized by means of MIDI technology. My principal objectives in creating this music were twofold: to explore some of the novel possibilities offered by Just Intonation and to make emotionally and intellectually satisfying music. I believe I have achieved both of these goals to a significant degree. ——David B. Doty The selections on this CD process—about synthesis, decisions. This is definitely detected in certain struc- were composed between sampling, and MIDI, about not experimental music, in tures and styles of elabora- approximately 1984 and Just Intonation, and about the Cageian sense—I am tion. More prominent are 1995 and recorded in 1998. what compositional styles more interested in result styles of polyphony from the All of them use some form and techniques are suited (aesthetic response) than Western European Middle of Just Intonation. This to various just tunings. process. Ages and Renaissance, method of tuning is com- Taken collectively, there It is tonal music (with a garage rock from the 1960s, mendable for its inherent is no conventional name lowercase t), music in which Balkan instrumental dance beauty, its variety, and its for the music that resulted hierarchic relations of tones music, the ancient Japanese long history (it is as old from this process, other are important and in which court music gagaku, Greek as civilization). -

Smufl Standard Music Font Layout

SMuFL Standard Music Font Layout Version 0.7 (2013-11-27) Copyright © 2013 Steinberg Media Technologies GmbH Acknowledgements This document reproduces glyphs from the Bravura font, copyright © Steinberg Media Technologies GmbH. Bravura is released under the SIL Open Font License and can be downloaded from http://www.smufl.org/fonts This document also reproduces some glyphs from the Unicode 6.2 code chart for the Musical Symbols range (http://www.unicode.org/charts/PDF/U1D100.pdf). These glyphs are the copyright of their respective copyright holders, listed on the Unicode Consortium web site here: http://www.unicode.org/charts/fonts.html 2 Version history Version 0.1 (2013-01-31) § Initial version. Version 0.2 (2013-02-08) § Added Tick barline. § Changed names of time signature, tuplet and figured bass digit glyphs to ensure that they are unique. § Add upside-down and reversed G, F and C clefs for canzicrans and inverted canons. § Added Time signature + and Time signature fraction slash glyphs. § Added Black diamond notehead, White diamond notehead, Half-filled diamond notehead, Black circled notehead, White circled notehead glyphs. § Added 256th and 512th note glyphs. § All symbols shown on combining stems now also exist as separate symbols. § Added reversed sharp, natural, double flat and inverted flat and double flat glyphs for canzicrans and inverted canons. § Added trill wiggle segment, glissando wiggle segment and arpeggiato wiggle segment glyphs. § Added string Half-harmonic, Overpressure down bow and Overpressure up bow glyphs. § Added Breath mark glyph. § Added angled beater pictograms for xylophone, timpani and yarn beaters. § Added alternative glyph for Half-open, per Weinberg. -

Standard Music Font Layout

SMuFL Standard Music Font Layout Version 0.5 (2013-07-12) Copyright © 2013 Steinberg Media Technologies GmbH Acknowledgements This document reproduces glyphs from the Bravura font, copyright © Steinberg Media Technologies GmbH. Bravura is released under the SIL Open Font License and can be downloaded from http://www.smufl.org/fonts This document also reproduces glyphs from the Sagittal font, copyright © George Secor and David Keenan. Sagittal is released under the SIL Open Font License and can be downloaded from http://sagittal.org This document also currently reproduces some glyphs from the Unicode 6.2 code chart for the Musical Symbols range (http://www.unicode.org/charts/PDF/U1D100.pdf). These glyphs are the copyright of their respective copyright holders, listed on the Unicode Consortium web site here: http://www.unicode.org/charts/fonts.html 2 Version history Version 0.1 (2013-01-31) § Initial version. Version 0.2 (2013-02-08) § Added Tick barline (U+E036). § Changed names of time signature, tuplet and figured bass digit glyphs to ensure that they are unique. § Add upside-down and reversed G, F and C clefs for canzicrans and inverted canons (U+E074–U+E078). § Added Time signature + (U+E08C) and Time signature fraction slash (U+E08D) glyphs. § Added Black diamond notehead (U+E0BC), White diamond notehead (U+E0BD), Half-filled diamond notehead (U+E0BE), Black circled notehead (U+E0BF), White circled notehead (U+E0C0) glyphs. § Added 256th and 512th note glyphs (U+E110–U+E113). § All symbols shown on combining stems now also exist as separate symbols. § Added reversed sharp, natural, double flat and inverted flat and double flat glyphs (U+E172–U+E176) for canzicrans and inverted canons. -

Pietro Aaron on Musica Plana: a Translation and Commentary on Book I of the Libri Tres De Institutione Harmonica (1516)

Pietro Aaron on musica plana: A Translation and Commentary on Book I of the Libri tres de institutione harmonica (1516) Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Matthew Joseph Bester, B.A., M.A. Graduate Program in Music The Ohio State University 2013 Dissertation Committee: Graeme M. Boone, Advisor Charles Atkinson Burdette Green Copyright by Matthew Joseph Bester 2013 Abstract Historians of music theory long have recognized the importance of the sixteenth- century Florentine theorist Pietro Aaron for his influential vernacular treatises on practical matters concerning polyphony, most notably his Toscanello in musica (Venice, 1523) and his Trattato della natura et cognitione de tutti gli tuoni di canto figurato (Venice, 1525). Less often discussed is Aaron’s treatment of plainsong, the most complete statement of which occurs in the opening book of his first published treatise, the Libri tres de institutione harmonica (Bologna, 1516). The present dissertation aims to assess and contextualize Aaron’s perspective on the subject with a translation and commentary on the first book of the De institutione harmonica. The extensive commentary endeavors to situate Aaron’s treatment of plainsong more concretely within the history of music theory, with particular focus on some of the most prominent treatises that were circulating in the decades prior to the publication of the De institutione harmonica. This includes works by such well-known theorists as Marchetto da Padova, Johannes Tinctoris, and Franchinus Gaffurius, but equally significant are certain lesser-known practical works on the topic of plainsong from around the turn of the century, some of which are in the vernacular Italian, including Bonaventura da Brescia’s Breviloquium musicale (1497), the anonymous Compendium musices (1499), and the anonymous Quaestiones et solutiones (c.1500). -

A Study of Microtones in Pop Music

University of Huddersfield Repository Chadwin, Daniel James Applying microtonality to pop songwriting: A study of microtones in pop music Original Citation Chadwin, Daniel James (2019) Applying microtonality to pop songwriting: A study of microtones in pop music. Masters thesis, University of Huddersfield. This version is available at http://eprints.hud.ac.uk/id/eprint/34977/ The University Repository is a digital collection of the research output of the University, available on Open Access. Copyright and Moral Rights for the items on this site are retained by the individual author and/or other copyright owners. Users may access full items free of charge; copies of full text items generally can be reproduced, displayed or performed and given to third parties in any format or medium for personal research or study, educational or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge, provided: • The authors, title and full bibliographic details is credited in any copy; • A hyperlink and/or URL is included for the original metadata page; and • The content is not changed in any way. For more information, including our policy and submission procedure, please contact the Repository Team at: [email protected]. http://eprints.hud.ac.uk/ Applying microtonality to pop songwriting A study of microtones in pop music Daniel James Chadwin Student number: 1568815 A thesis submitted to the University of Huddersfield in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts University of Huddersfield May 2019 1 Abstract While temperament and expanded tunings have not been widely adopted by pop and rock musicians historically speaking, there has recently been an increased interest in microtones from modern artists and in online discussion. -

Mto.95.1.4.Cuciurean

Volume 1, Number 4, July 1995 Copyright © 1995 Society for Music Theory John D. Cuciurean KEYWORDS: scale, interval, equal temperament, mean-tone temperament, Pythagorean tuning, group theory, diatonic scale, music cognition ABSTRACT: In Mathematical Models of Musical Scales, Mark Lindley and Ronald Turner-Smith attempt to model scales by rejecting traditional Pythagorean ideas and applying modern algebraic techniques of group theory. In a recent MTO collaboration, the same authors summarize their work with less emphasis on the mathematical apparatus. This review complements that article, discussing sections of the book the article ignores and examining unique aspects of their models. [1] From the earliest known music-theoretical writings of the ancient Greeks, mathematics has played a crucial role in the development of our understanding of the mechanics of music. Mathematics not only proves useful as a tool for defining the physical characteristics of sound, but abstractly underlies many of the current methods of analysis. Following Pythagorean models, theorists from the middle ages to the present day who are concerned with intonation and tuning use proportions and ratios as the primary language in their music-theoretic discourse. However, few theorists in dealing with scales have incorporated abstract algebraic concepts in as systematic a manner as the recent collaboration between music scholar Mark Lindley and mathematician Ronald Turner-Smith.(1) In their new treatise, Mathematical Models of Musical Scales: A New Approach, the authors “reject the ancient Pythagorean idea that music somehow &lsquois’ number, and . show how to design mathematical models for musical scales and systems according to some more modern principles” (7). -

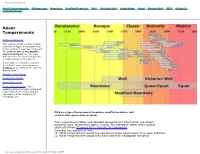

Temperaments Visualized

Temperaments Visualized About Temperaments • Pythagorean • Meantone • Modified Meantone • Well • Victorian Well • Quasi-Equal • Equal • Modern Well • EBVT • Return to rollingball home About Temperaments Historical Overview This section contains a brief graphic overview of types of temperaments in the context of classical composers. The bottom half of the graphic has live hotspots, but the upper half (with the names of composers) is sadly lacking in interactivity. If you click on a miniature and get the full-size chart, you can press backspace to return to the current History image. Homage to Jorgensen Reading the Charts About "Key Color" Temperamental links - other websites sites of interest will appear in the frame to the right, and you can explore while remaining at rollingball.com... Click on a type of temperament (meantone, modified meantone, well, victorian well, quasi-equal, or equal). The temperament dates and detailed temperament information are drawn primarily from Jorgensen's tome, Tuning. The composer dates were quickly abstracted from Classical Net's Timeline of Composers. Consider two aspects of this: (1) What temperament would the composers have heard when they were children? (2) What temperament would they have had their keyboards tuned to? http://www.rollingball.com/TemperamentsFrames.htm10/2/2006 4:13:04 PM About Temperaments About Temperaments Historical Overview This section contains a brief graphic overview of types of temperaments in the context of classical composers. The bottom half of the graphic has live hotspots, but the upper half (with the names of composers) is sadly lacking in interactivity. If you click on a miniature and get the full-size chart, you can press backspace to return to the current History image. -

Musical Techniques

Musical Techniques Musical Techniques Frequencies and Harmony Dominique Paret Serge Sibony First published 2017 in Great Britain and the United States by ISTE Ltd and John Wiley & Sons, Inc. Apart from any fair dealing for the purposes of research or private study, or criticism or review, as permitted under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, this publication may only be reproduced, stored or transmitted, in any form or by any means, with the prior permission in writing of the publishers, or in the case of reprographic reproduction in accordance with the terms and licenses issued by the CLA. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside these terms should be sent to the publishers at the undermentioned address: ISTE Ltd John Wiley & Sons, Inc. 27-37 St George’s Road 111 River Street London SW19 4EU Hoboken, NJ 07030 UK USA www.iste.co.uk www.wiley.com © ISTE Ltd 2017 The rights of Dominique Paret and Serge Sibony to be identified as the authors of this work have been asserted by them in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. Library of Congress Control Number: 2016960997 British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A CIP record for this book is available from the British Library ISBN 978-1-78630-058-4 Contents Preface ........................................... xiii Introduction ........................................ xv Part 1. Laying the Foundations ............................ 1 Introduction to Part 1 .................................. 3 Chapter 1. Sounds, Creation and Generation of Notes ................................... 5 1.1. Physical and physiological notions of a sound .................. 5 1.1.1. Auditory apparatus ............................... 5 1.1.2. Physical concepts of a sound .......................... 7 1.1.3. -

European Philosophy and the Triumph of Equal Temperament/ Noel David Hudson University of Massachusetts Amherst

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014 2007 Abandoning nature :: European philosophy and the triumph of equal temperament/ Noel David Hudson University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/theses Hudson, Noel David, "Abandoning nature :: European philosophy and the triumph of equal temperament/" (2007). Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014. 1628. Retrieved from https://scholarworks.umass.edu/theses/1628 This thesis is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014 by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ABANDONING NATURE: EUROPEAN PHILOSOPHY AND THE TRIUMPH OF EQUAL TEMPERAMENT A Thesis Presented by NOEL DAVID HUDSON Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts Amherst in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS February 2007 UMASS/Five College Graduate Program in History © Copyright by Noel David Hudson 2006 All Rights Reserved ABANDONING NATURE: EUROPEAN PHILOSOPHY AND THE TRIUMPH OF EQUAL TEMPERAMENT A Thesis Presented by NOEL DAVID HUDSON Approved as to style and content by: Daniel Gordon, th^ir Bruce Laurie, Member Brian Ogilvie, Member Audrey Altstadt, Department Head Department of History CONTKNTS ( HAPTER Page 1. [NTR0D1 f< i ion 2. what is TEMPERAMENT? 3. THE CLASSICAL LEGACY 4. THE ENGLISH, MUSICAL INSTRUMENTS, AND OTHER PROBLEMS 5. A TROUBLING SOLUTION (>. ANCIEN1 HABITS OF MUSICAL THOUGHT IN THE "NEW PHILOSOPHY" 7. FROM THEORY TO PRACTICE X. A THEORETICAL INTERLUDE 9. -

Lute Tuning and Temperament in the Sixteenth and Seventeenth Centuries

LUTE TUNING AND TEMPERAMENT IN THE SIXTEENTH AND SEVENTEENTH CENTURIES BY ADAM WEAD Submitted to the faculty of the Jacobs School of Music in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree, Doctor of Music, Indiana University August, 2014 Accepted by the faculty of the Jacobs School of Music, Indiana University, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Music. Nigel North, Research Director & Chair Stanley Ritchie Ayana Smith Elisabeth Wright ii Contents Acknowledgments . v Introduction . 1 1 Tuning and Temperament 5 1.1 The Greeks’ Debate . 7 1.2 Temperament . 14 1.2.1 Regular Meantone and Irregular Temperaments . 16 1.2.2 Equal Division . 19 1.2.3 Equal Temperament . 25 1.3 Describing Temperaments . 29 2 Lute Fretting Systems 32 2.1 Pythagorean Tunings for Lute . 33 2.2 Gerle’s Fretting Instructions . 37 2.3 John Dowland’s Fretting Instructions . 46 2.4 Ganassi’s Regola Rubertina .......................... 53 2.4.1 Ganassi’s Non-Pythagorean Frets . 55 2.5 Spanish Vihuela Sources . 61 iii 2.6 Sources of Equal Fretting . 67 2.7 Summary . 71 3 Modern Lute Fretting 74 3.1 The Lute in Ensembles . 76 3.2 The Theorbo . 83 3.2.1 Solutions Utilizing Re-entrant Tuning . 86 3.2.2 Tastini . 89 3.2.3 Other Solutions . 95 3.3 Meantone Fretting in Tablature Sources . 98 4 Summary of Solutions 105 4.1 Frets with Fixed Semitones . 106 4.2 Enharmonic Fretting . 110 4.3 Playing with Ensembles . 113 4.4 Conclusion . 118 A Complete Fretting Diagrams 121 B Fret Placement Guide 124 C Calculations 127 C.1 Hans Gerle . -

Tuning Continua and Keyboard Layouts

October 4, 2007 8:34 Journal of Mathematics and Music TuningContinua-RevisedVersion Journal of Mathematics and Music Vol. 00, No. 00, March 2007, 1–15 Tuning Continua and Keyboard Layouts ANDREW MILNE∗ , WILLIAM SETHARES , and JAMES PLAMONDON † ‡ § Department of Music, P.O. Box 35, FIN-40014, University of Jyvaskyl¨ a,¨ Finland. Email: [email protected] † 1415 Engineering Drive, Dept Electrical and Computer Engineering, University of Wisconsin, Madison, WI 53706 USA. ‡ Phone: 608-262-5669. Email: [email protected] CEO, Thumtronics Inc., 6911 Thistle Hill Way, Austin, TX 78754 USA. Phone: 512-363-7094. Email: § [email protected] (received April 2007) Previous work has demonstrated the existence of keyboard layouts capable of maintaining consistent fingerings across a parameterised family of tunings. This paper describes the general principles underlying layouts that are invariant in both transposition and tuning. Straightforward computational methods for determining appropriate bases for a regular temperament are given in terms of a row-reduced matrix for the temperament-mapping. A concrete description of the range over which consistent fingering can be maintained is described by the valid tuning range. Measures of the resulting keyboard layouts allowdirect comparison of the ease with which various chordal and scalic patterns can be fingered as a function of the keyboard geometry. A number of concrete examples illustrate the generality of the methods and their applicability to a wide variety of commas and temperaments, tuning continua, and keyboard layouts. Keywords: Temperament; Comma; Layout; Button-Lattice; Swathe; Isotone 2000 Mathematics Subject Classification: 15A03; 15A04 1 Introduction Some alternative keyboard designs have the property that any given interval is fingered the same in all keys.