Evaluation of the Innovations in Community-Based Crime Reduction (CBCR) Program: Executive Summary and Final Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lots of Glass, Not Enough Cash

BROOKLYN’S REAL NEWSPAPERS Including The Bensonhurst Paper Published every Saturday — online all the time — by Brooklyn Paper Publications Inc, 55 Washington St, Suite 624, Brooklyn NY 11201. Phone 718-834-9350 • www.BrooklynPapers.com • © 2006 Brooklyn Paper Publications • 12 pages •Vol. 29, No. 1 BWN • Saturday, January 7, 2006 • FREE THE NEW BROOKLYN PUBLIC LIBRARY LOTS OF GLASS, NOT ENOUGH CASH / Julie Rosenberg The Brooklyn Papers The Brooklyn Babies of the New Year are here! Enrique Norten / TEN Arquitectos A rendering of the proposed Brooklyn Public Library Visual and Performing Arts branch (right) at Flatbush and Lafayette avenues in Fort Greene, next to the proposed Frank Gehry-designed Theatre for a New Audience (center). The two buildings would stand next to the Brooklyn Academy of Music’s Neo-Itlaianate structure (left). By Ariella Cohen To jumpstart the latest fundraising in serious doubt. poration, while another $3 million “It is very seductive and appeal- The Brooklyn Papers campaign, on Tuesday, the library “In a perfect world, we are talking was given by the City Council and ing, but you have to ask some hard had Norten show off tweaks in his about building in the next four or directly from the Bloomberg admin- questions about how a project like The building is clear, but who well-received design to the library’s five years,” said Cooper. “But we stration. Another $2 million came this will be subsidized and sus- will pay for it remains murky. board of trustees. have to find funding first.” from Albany. tained,” said Marilyn Gelber, execu- Brooklyn Public Library admitted The project’s glistening architec- Raising money for projects in Down- Part of Norten’s presentation was tive director of Independence Com- last week that it is struggling to raise tural benchmarks remain, but now town Brooklyn — even ones attached simply to remind the library board of munity Bank Foundation. -

Bldg ID: K650 HARRY VANARSDALE VOC HS(WHITNEY)-K Geo District: 14

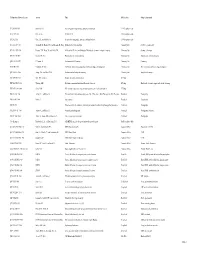

2018 - 2019 Bldg ID: K650 HARRY VANARSDALE VOC HS(WHITNEY)-K Geo District: 14 Bldg Address: 257 N 6TH STREET Survey Principal: MICHAEL SHADRICK Added Room Room Number Changed Primary 2018 - 2019 Room 2017 - 2018 2018 - 2019 Function Sharing Room No Org Name SQFT AC Room Function Room Function Used % Y/N 101 BROOKLYN PREPARATORY HS - K 696 Y REGULAR CLASSROOM REGULAR CLASSROOM 50 - 100 N 102 BROOKLYN PREPARATORY HS - K 713 Y REGULAR CLASSROOM REGULAR CLASSROOM 50 - 100 N 103 BROOKLYN PREPARATORY HS - K 638 Y REGULAR CLASSROOM REGULAR CLASSROOM 50 - 100 N 104 BROOKLYN PREPARATORY HS - K 506 Y AP'S OFFICE AP'S OFFICE 50 - 100 N 105 BROOKLYN PREPARATORY HS - K 667 Y REGULAR CLASSROOM REGULAR CLASSROOM 50 - 100 N 106 BROOKLYN PREPARATORY HS - K 696 Y REGULAR CLASSROOM REGULAR CLASSROOM 50 - 100 N 107 BROOKLYN PREPARATORY HS - K 638 Y REGULAR CLASSROOM REGULAR CLASSROOM 50 - 100 N 108 BROOKLYN PREPARATORY HS - K 190 Y AP'S OFFICE AP'S OFFICE 50 - 100 N 109 BROOKLYN PREPARATORY HS - K 621 Y DEAN'S OFFICE DEAN'S OFFICE 50 - 100 N 110 BROOKLYN PREPARATORY HS - K 667 Y REGULAR CLASSROOM REGULAR CLASSROOM 50 - 100 N 111 BROOKLYN PREPARATORY HS - K 744 Y REGULAR CLASSROOM REGULAR CLASSROOM 50 - 100 N TEACHER'S 112 BROOKLYN PREPARATORY HS - K 255 N TEACHER'S CAFETERIA 50 - 100 N CAFETERIA 113 BROOKLYN PREPARATORY HS - K 638 Y REGULAR CLASSROOM REGULAR CLASSROOM 50 - 100 N REGULAR CLASSROOM - HS REGULAR CLASSROOM 121 BROOKLYN PREPARATORY HS - K 650 Y 50 - 100 N GRADES - HS GRADES 122 BROOKLYN PREPARATORY HS - K 784 Y REGULAR CLASSROOM REGULAR CLASSROOM -

SEARCH PROSPECTUS: Dean of the School of Management TABLE of CONTENTS

SEARCH PROSPECTUS: Dean of the School of Management TABLE OF CONTENTS OVERVIEW OF THE SEARCH 3 HISTORY OF KETTERING UNIVERSITY 4 THE COMMUNITY OF FLINT AND REGION 5 ABOUT KETTERING UNIVERSITY AND ACADEMIC LIFE 6 MISSION, VISION, VALUES AND PILLARS OF SUCCESS 6 SCHOOL LEADERSHIP AND GOVERNANCE 7 ACCOLADES AND POINTS OF PRIDE AT KETTERING UNIVERSITY 7 UNIVERSITY FINANCES 7 ACADEMIC PROGRAMS 7 INTERNATIONAL PROGRAMS AND OPPORTUNITIES 8 KETTERING UNIVERSITY ONLINE (KUO)/KETTERING GLOBAL 9 ACCREDITATION 9 THE SCHOOL OF MANAGEMENT 9 STUDENTS AND ALUMNI 10 STUDENTS AND STUDENT LIFE 10 ALUMNI AND ALUMNI ACCOLADES 10 SENIOR VICE PRESIDENT FOR ACADEMIC AFFAIRS AND PROVOST 11 LEADERSHIP AGENDA FOR THE DEAN OF THE SCHOOL OF MANAGEMENT 12 REQUIRED QUALIFICATIONS 12 DESIRED EXPERIENCE, KNOWLEDGE, AND ATTRIBUTES 13 PROCEDURES FOR NOMINATIONS AND APPLICATIONS 14 SEARCH PROSPECTUS: Dean of the School of Management 2 OVERVIEW OF THE SEARCH Kettering University, a private (nonprofit) co- It is an exciting time of energy, innovation, successes, educational institution in Flint, Michigan, invites challenges, and opportunities at Kettering University. nominations for and inquiries and applications The institution is a unique national leader in from individuals interested in a transformational experiential STEM and business education, integrating leadership opportunity as Dean of the School an intense curriculum with applied professional of Management. This position carries with it an experience. Students realize their potential and endowed chair title of Riopelle Endowed Chair of advance their ideas by combining theory and practice. Engineering Management. The Dean is expected to be an effective collaborative partner with Provost Dr. In June 2019 Kettering University announced a $150 James Z. -

Flint Fights Back, Environmental Justice And

Thank you for your purchase of Flint Fights Back. We bet you can’t wait to get reading! By purchasing this book through The MIT Press, you are given special privileges that you don’t typically get through in-device purchases. For instance, we don’t lock you down to any one device, so if you want to read it on another device you own, please feel free to do so! This book belongs to: [email protected] With that being said, this book is yours to read and it’s registered to you alone — see how we’ve embedded your email address to it? This message serves as a reminder that transferring digital files such as this book to third parties is prohibited by international copyright law. We hope you enjoy your new book! Flint Fights Back Urban and Industrial Environments Series editor: Robert Gottlieb, Henry R. Luce Professor of Urban and Environmental Policy, Occidental College For a complete list of books published in this series, please see the back of the book. Flint Fights Back Environmental Justice and Democracy in the Flint Water Crisis Benjamin J. Pauli The MIT Press Cambridge, Massachusetts London, England © 2019 Massachusetts Institute of Technology All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form by any electronic or mechanical means (including photocopying, recording, or information storage and retrieval) without permission in writing from the publisher. This book was set in Stone Serif by Westchester Publishing Services. Printed and bound in the United States of America. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Pauli, Benjamin J., author. -

Atwood Football Memories by Lawrence R

East VillaMgagaezine Photograph by Edwin D. Custer VERN’S COLLISION INC. Free Loaners • Unibody • Frame • Paint Specialists • Glass • State-certified Mechanics More than 40 years at the same location. (810) 232-6751 2409 Davison Rd. Senior Living Simplified Near College Cultural Center Easy Expressway Access Immediate Occupancy! Call today to reserve BATTISTE’S Managed by the Piper Management Group your new TEMPLE DINING ROOM (Rents start at $415) home! PUBLIC WELCOME 800 E. Court St. Serving Downtown Flint since 1947 Luncheon Monday-Friday 11 a.m. - 2 p.m. 810-239-4400 All Occasion Catering TDD: 810-649-3777 235-7760 Equal Housing Opportunity FREE Home Warranty Flint’s Resident Realtor — The Name Trusted in More Neighborhoods Ryan Eashoo (810) 234-1234 2 Editorial How about some help? By Jan Worth-Nelson A year ago, just two issues before he “These are the people in the co-op who EastMagazine Village died, our founder and late publisher Gary contribute the 500 to 700 hours needed to Vol. LIII No. 11 December 2015 Custer wrote an editorial asking for con - produce the magazine each month – a tributions to East Village Magazine . continuation of the tradition begun in Founder Gary P. Custer He asked, “Is there still a place for East 1976.” Village Magazine Editor Jan Worth-Nelson , or are we a dinosaur [The website, eastvillagemagazine.org, that should fade into history?” is coming back after a major break last Managing Editor Nic Custer As EVM heads into its 40th year and spring; thanks to the patient work of our Ad Manager Daniel Kienitz the end of our first year without Gary, we tech consultant Dean Paxton we are back Copy Editor Danielle Ward find ourselves thinking hard about all that in business with a new design and many Reporters Nic Custer – about who and what we are – and, per - new options — work on that continues.] Andrew Keast haps most importantly, why we are. -

B2150-B FRONT Final

Bedrock Geology of the Paducah 1°×2° CUSMAP Quadrangle, Illinois, Indiana, Kentucky, and Missouri By W. John Nelson THE PADUCAH CUSMAP QUADRANGLE: RESOURCE AND TOPICAL INVESTIGATIONS Martin B. Goldhaber, Project Coordinator T OF EN TH TM E U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY BULLETIN 2150–B R I A N P T E E R D . I O S . R A joint study conducted in collaboration with the Illinois State Geological U Survey, the Indiana Geological Survey, the Kentucky Geological Survey, and the Missouri M 9 Division of Geology and Land Survey A 8 4 R C H 3, 1 UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE, WASHINGTON : 1998 U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR BRUCE BABBITT, Secretary U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Mark Schaefer, Acting Director For sale by U.S. Geological Survey, Information Services Box 25286, Federal Center Denver, CO 80225 Any use of trade, product, or firm names in this publication is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Government Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Nelson, W. John Bedrock geology of the Paducah 1°×2° CUSMAP Quadrangle, Illinois, Indiana, Ken- tucky, and Missouri / by W. John Nelson. p. cm.—(U.S. Geological Survey bulletin ; 2150–B) (The Paducah CUSMAP Quadrangle, resource and topical investigations ; B) Includes bibliographical references. Supt. of Docs. no. : I 19.3:2150–B 1. Geology—Middle West. I. Title. II. Series. III. Series: The Paducah CUSMAP Quadrangle, resource and topical investigations ; B QE75.B9 no. 2150–B [QE78.7] [557.3 s—dc21 97–7724 [557.7] CIP CONTENTS Abstract .......................................................................................................................... -

JOIDES Resolution Library

Call number (Dewey dec. sys.) Author Title JR Location Subject, key words TN 269 S64 1985 Spradley, L.H. Surveying and navigation for geophysical exploration U/W Geophysics Lab TN 271 P4 C63 Cofeen, J.A. QC 242.2 C55 U/W Geophysics Lab QC 242.2 C55 Clay, C.S., and Medwin, H. Acoustical oceanography: principles and applications U/W Geophysics Lab GC 101.2 G7 1983 Grasshoff, K., Ehrhardt, E., and Kremlin, K. (Eds.) Methods of Seawater Analysis Chemistry Lab Seawater, geochemistry GC 101.2 P37 1984 Parsons, T.R., Maita, Y., and Lalli, C.M. A Manual of Chemical and Biological Methods for Seawater Analysis (2 copies) Chemistry Lab Seawater, chemistry GC 380.2 G3 N37 Kaplan, I.R. (Ed.) Natural gases in marine sediments Chemistry Lab Natural gases, marine sediments QD 31.2 O25 1977 O’Connor, R. Fundamentals of Chemistry Chemistry Lab Chemistry RS 51 M4 1984 Windholz, M. (Ed.) The Merck index: an encyclopedia of chemicals, drugs, and biologicals Chemistry Lab Reference book, chemicals, drugs, biologicals QD 75.2 S55 1982 Skoog, D.A., and West, D.M. Fundamentals of analytical chemistry Chemistry Lab Analytical chemistry TK 7804 H6 1984 Graf, R.F. (Comp.) Modern dictionary of Electronics ET Shop TK 7868 W285 1983 Warring, R.H. Electronic components handbook for circuit designers ET Shop Handbook, electronic components, circuit designing TK 7887.5 S48 1984 Seyer, M.D. RS-232 made easy: connecting computers, printers, terminals, and modems ET Shop TR 145 A38 1984 Adams, A., and Baker, R. The new Ansel Adams photography series: Bk. -

St. Paul's 30Th Annual Auction

ST. PAUL’S 30TH ANNUAL AUCTION Saturday, December 1, 2018, doors open at 5 p.m. St. Paul’s Parish Hall, 199 Carroll St. Pottery by Art Stewart © 2018 Pottery by Admission $40 per Adult, includes: Fun Silent Auction, Entertaining Live Auction, Appetizers, and Light Supper Tickets going fast! Buy now! contact [email protected] or call 718-625-4126 Click image for more information A once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to tour the Holyland with fellow St. Paulies! Travel to Galilee, Jerusalem, Bethlehem, and Tel Aviv, for one person for 10 days. • Trip from New York Area Gateway • Airport-hotel transfers (includes fuel surcharges and taxes) • Hotel taxes • Accommodations in superior tourist • Touring by Private Motorcoach class hotels • Services of a Professional Tour Escort • All breakfast and dinners • Sightseeing as per itinerary Click image to launch website Harry Potter & the Cursed Child Parts 1 & 2 CALLING ALL MUGGLES! Come be dazzled by the two-part sequel to the Harry Potter phenomenon that took the London stage by storm, written by JK Rowling and Jack Thorne. Harry Potter & the Cursed Child, Parts One and Two - Tickets for 2 on Thursday May 30th & Friday May 31st , 2019 at 7:30pm, Balcony Seats Row H 106 & 107 (center of the last row of the balcony) at the Lyric Theatre, Lyric Theatre, 214 W 43rd St, New York, NY 10036 Sail Breathtaking New York Harbor on a 24-FootSail the KeelboatBreathtaking New York Harbor Join Nancy Webster for a memorable sail for three people on a J-80 keelboat in New York Harbor, passing Ellis Island, the Statue of Liberty, Governor’s Island, and the Red Hook pier. -

State of the City Address 2016 Dr. Karen Weaver, Mayor of Flint Flint, Michigan / August 4, 2016

FINAL VERSION State of the City Address 2016 Dr. Karen Weaver, Mayor of Flint Flint, Michigan / August 4, 2016 Good evening. It is an honor to address the people of Flint at my first-ever State of the City address. I appreciate the many citizens and leaders from government, business, churches, and the community who have chosen to attend today, especially Congressman Dan Kildee and Lansing Mayor Virg Bernero, and I am grateful for the steadfast support you have shown the City of Flint as it deals with a shocking and unprecedented drinking water crisis. Despite that crisis, the resolve to make our city of Flint greater than ever has never been stronger. We are determined to continue the upward trend Flint was on before this crisis hit, when new restaurants and businesses were opening, revitalization was underway, and entrepreneurship was taking hold, along with a growing faith in the future. Those positive changes mean that, once again, we’re enjoying Atwood Stadium as an anchor in downtown Flint, a place we can watch our great sports teams play now it has been renovated by Kettering University. And who isn’t looking forward to next year’s reopening of the Capitol Theatre, which will be restored to its historical glory thanks to the state, the Charles Stewart Mott Foundation and the Hagerman Foundation? Isn’t it positive that new companies are moving into Flint and creating expanded job opportunities, such as iSource Worldwide’s $2.7 million investment and 100 new jobs for the Dryden Building? Aren’t we excited to see the long-vacant Chevy in the Hole property being transformed into a wonderful community park and into Kettering University’s new automotive training ground? Flint is a wonderful place to live, and we plan to create an even better city in the days ahead. -

Surface Water Supply of the United States 1947

« Surface Water Supply of the United States 1947 Part 14. Pacific Slope Basins in Oregon and Lower Columbia River Basin Prepared under the direction of C. G. PAULSEN, Chief Hydraulic Engineer GEOLOGICAL SURVEY WATER-SUPPLY PAPER 1094 Prepared in cooperation with the States of Oregon and ff^ashington and other agencies copy is PUBLIC PROPERTY and is not to beiremoved from the official files. PRIVATE POSSSSiON IS UNLAWFUL (R- S. Sup. Vol. 2, pp. 380, Sec.TMS) UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE, WASHINGTON -. 1950 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR Oscar L. Chapman, Secretary GEOLOGICAL SURVEY W. E. Wrather, Director For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U. S. Government Printing Office Washington 25, D. C. - Price 55 cents (paper cover) PREFACE This report was prepared by the Geological Survey in cooperation with the States of Oregon and Washington and other agencies, by personnel of the Water Resources Division under the direction of: C. G. Paulsen___________________ Chief Hydraulic Engineer J. V. B. Wells_________________ Chief, Surface Water Branch B. J. Peterson________________ Chief, Annual Reports Section District Engineers (Surface Water) G. H. Canfield_________________________ Portland, Oreg. F. M. Veatch__________________________ Tacoma, Wash. in CONTENTS Page Scope of work.......................................................................: 1 Definition of terms.................................................................. 1 Explanation of data................................................................. -

Paws to Reflect Hawke Also Stars in the Film

REAL ESTATE P12 P9 HOME ‘Cheesy’ BROOKLYN Back to DELIVERED SERVICES P13 senator to SMART work for THROUGHOUT visit Slope BRIEFS BROWNSTONE BROOKLYN EMPLOYMENT mom Hepcat BROOKLYN’S REAL NEWSPAPERS Including The Brooklyn Heights Paper, Carroll Gardens-Cobble Hill Paper, DUMBO Paper and the Downtown News Published every Saturday — online all the time — by Brooklyn Paper Publications Inc, 55 Washington St, Suite 624, Brooklyn NY 11201. Phone 718-834-9350 • www.BrooklynPapers.com • © 2006 Brooklyn Paper Publications • 14 pages •Vol. 29, No. 10 BWN • Saturday, March 11, 2006 • FREE CUT! THIS WEEKEND After complaints, movie crews banned in Heights By Ariella Cohen For some Brooklyn Heights residents, the deci- The Brooklyn Papers sion to restrict new filming permits didn’t come a Cut — that’s a wrap. In Brooklyn Heights, at least. moment too soon. After three big-budget movie crews turned the Last week, the already cramped neighborhood scenic neighborhood into a Hollywood backlot last was overrun with film crews — and their big movie week, the city announced that it would bar future star trailers, catering trucks and equipment rigs. filming there for three months. On Thursday and Friday, Warner Bros. rented St. Ann’s and the Holy Trinity Church to film the Kirsten Sher- idan-helmed “August Rush.” And on Thursday, author-ac- tor-director Ethan Hawke was on the Promenade shooting the film version of his angst-ridden City: Free novel, “The Hottest State.” Paws to reflect Hawke also stars in the film. And the next morning on Cadman Plaza West, dog-walk- ers were displaced by a white Wegman show kicks off at B’klyn Museum parking on trailer labeled “Lucy” and “Desi” that served the crew of a Castle Rock remake of “Mostly By Lisa J. -

FY 2020 Adopted Capital Commitment Plan

The City of New York Adopted Capital Commitment Plan Fiscal Year 2020 Volume 4 Bill de Blasio, Mayor Mayor’s Office of Management and Budget Melanie Hartzog, Director FY 2020 Adopted Budget Capital Commitment Plan Agency Index Department No. Department Name Volume Page 125 Aging, Department for the (AG) .......................................................................................... 1 1 801 Business Services, Department of Economic Development, Office of (ED) ................................................................ 1 120 068 Children’s Services, Administration for (CS) ...................................................................... 1 78 042 City University of New York (HN) ...................................................................................... 2 573 856 Citywide Administrative Services, Department of Courts (CO) ............................................................................................................ 1 53 Equipment and Miscellaneous (PU) ....................................................................... 3 1211 Public Buildings (PW) ........................................................................................... 4 1585 Real Property (RE) ................................................................................................. 4 1736 072 Correction, Department of (C).............................................................................................. 1 33 126 Cultural Affairs, Department of (PV) ..................................................................................