Testing the Chemical Tagging Technique with Open Clusters Sergi Blanco-Cuaresma

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Minor Planet Bulletin

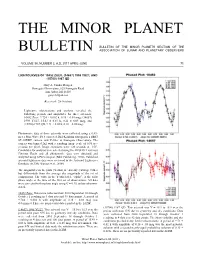

THE MINOR PLANET BULLETIN OF THE MINOR PLANETS SECTION OF THE BULLETIN ASSOCIATION OF LUNAR AND PLANETARY OBSERVERS VOLUME 38, NUMBER 2, A.D. 2011 APRIL-JUNE 71. LIGHTCURVES OF 10452 ZUEV, (14657) 1998 YU27, AND (15700) 1987 QD Gary A. Vander Haagen Stonegate Observatory, 825 Stonegate Road Ann Arbor, MI 48103 [email protected] (Received: 28 October) Lightcurve observations and analysis revealed the following periods and amplitudes for three asteroids: 10452 Zuev, 9.724 ± 0.002 h, 0.38 ± 0.03 mag; (14657) 1998 YU27, 15.43 ± 0.03 h, 0.21 ± 0.05 mag; and (15700) 1987 QD, 9.71 ± 0.02 h, 0.16 ± 0.05 mag. Photometric data of three asteroids were collected using a 0.43- meter PlaneWave f/6.8 corrected Dall-Kirkham astrograph, a SBIG ST-10XME camera, and V-filter at Stonegate Observatory. The camera was binned 2x2 with a resulting image scale of 0.95 arc- seconds per pixel. Image exposures were 120 seconds at –15C. Candidates for analysis were selected using the MPO2011 Asteroid Viewing Guide and all photometric data were obtained and analyzed using MPO Canopus (Bdw Publishing, 2010). Published asteroid lightcurve data were reviewed in the Asteroid Lightcurve Database (LCDB; Warner et al., 2009). The magnitudes in the plots (Y-axis) are not sky (catalog) values but differentials from the average sky magnitude of the set of comparisons. The value in the Y-axis label, “alpha”, is the solar phase angle at the time of the first set of observations. All data were corrected to this phase angle using G = 0.15, unless otherwise stated. -

The Minor Planet Bulletin

THE MINOR PLANET BULLETIN OF THE MINOR PLANETS SECTION OF THE BULLETIN ASSOCIATION OF LUNAR AND PLANETARY OBSERVERS VOLUME 35, NUMBER 3, A.D. 2008 JULY-SEPTEMBER 95. ASTEROID LIGHTCURVE ANALYSIS AT SCT/ST-9E, or 0.35m SCT/STL-1001E. Depending on the THE PALMER DIVIDE OBSERVATORY: binning used, the scale for the images ranged from 1.2-2.5 DECEMBER 2007 – MARCH 2008 arcseconds/pixel. Exposure times were 90–240 s. Most observations were made with no filter. On occasion, e.g., when a Brian D. Warner nearly full moon was present, an R filter was used to decrease the Palmer Divide Observatory/Space Science Institute sky background noise. Guiding was used in almost all cases. 17995 Bakers Farm Rd., Colorado Springs, CO 80908 [email protected] All images were measured using MPO Canopus, which employs differential aperture photometry to determine the values used for (Received: 6 March) analysis. Period analysis was also done using MPO Canopus, which incorporates the Fourier analysis algorithm developed by Harris (1989). Lightcurves for 17 asteroids were obtained at the Palmer Divide Observatory from December 2007 to early The results are summarized in the table below, as are individual March 2008: 793 Arizona, 1092 Lilium, 2093 plots. The data and curves are presented without comment except Genichesk, 3086 Kalbaugh, 4859 Fraknoi, 5806 when warranted. Column 3 gives the full range of dates of Archieroy, 6296 Cleveland, 6310 Jankonke, 6384 observations; column 4 gives the number of data points used in the Kervin, (7283) 1989 TX15, 7560 Spudis, (7579) 1990 analysis. Column 5 gives the range of phase angles. -

The V-Band Photometry of Asteroids from ASAS-SN

Astronomy & Astrophysics manuscript no. 40759˙ArXiV © ESO 2021 July 22, 2021 V-band photometry of asteroids from ASAS-SN Finding asteroids with slow spin ? J. Hanusˇ1, O. Pejcha2, B. J. Shappee3, C. S. Kochanek4;5, K. Z. Stanek4;5, and T. W.-S. Holoien6;?? 1 Institute of Astronomy, Faculty of Mathematics and Physics, Charles University, V Holesoviˇ ckˇ ach´ 2, 18000 Prague, Czech Republic 2 Institute of Theoretical Physics, Faculty of Mathematics and Physics, Charles University, V Holesoviˇ ckˇ ach´ 2, 18000 Prague, Czech Republic 3 Institute for Astronomy, University of Hawai’i, 2680 Woodlawn Drive, Honolulu, HI 96822, USA 4 Department of Astronomy, The Ohio State University, 140 West 18th Avenue, Columbus, OH 43210, USA 5 Center for Cosmology and Astroparticle Physics, The Ohio State University, 191 W. Woodruff Avenue, Columbus, OH 43210, USA 6 The Observatories of the Carnegie Institution for Science, 813 Santa Barbara St., Pasadena, CA 91101, USA Received x-x-2021 / Accepted x-x-2021 ABSTRACT We present V-band photometry of the 20,000 brightest asteroids using data from the All-Sky Automated Survey for Supernovae (ASAS-SN) between 2012 and 2018. We were able to apply the convex inversion method to more than 5,000 asteroids with more than 60 good measurements in order to derive their sidereal rotation periods, spin axis orientations, and shape models. We derive unique spin state and shape solutions for 760 asteroids, including 163 new determinations. This corresponds to a success rate of about 15%, which is significantly higher than the success rate previously achieved using photometry from surveys. -

The Minor Planet Bulletin Semi-Major Axis of 2.317 AU, Eccentricity 0.197, Inclination 7.09 (Warner Et Al., 2018)

THE MINOR PLANET BULLETIN OF THE MINOR PLANETS SECTION OF THE BULLETIN ASSOCIATION OF LUNAR AND PLANETARY OBSERVERS VOLUME 45, NUMBER 3, A.D. 2018 JULY-SEPTEMBER 215. LIGHTCURVE ANALYSIS FOR TWO NEAR-EARTH 320ʺ/min during the close approach. The eclipse was observed, ASTEROIDS ECLIPSED BY EARTH’S SHADOW within minutes of the original prediction. Preliminary rotational and eclipse lightcurves were made available soon after the close Peter Birtwhistle approach (Birtwhistle, 2012; Birtwhistle, 2013; Miles, 2013) but it Great Shefford Observatory should be noted that a possible low amplitude 8.7 h period (Miles, Phlox Cottage, Wantage Road 2013) has been discounted in this analysis. Great Shefford, Berkshire, RG17 7DA United Kingdom Several other near-Earth asteroids are known to have been [email protected] eclipsed by the Earth’s shadow, e.g. 2008 TC3 and 2014 AA (both before impacting Earth), 2012 KT42, and 2016 VA (this paper) (Received 2018 March18) but internet searches have not found any eclipse lightcurves. The asteroid lightcurve database (LCDB; Warner et al., 2009) lists a Photometry was obtained from Great Shefford reference to an unpublished result for 2012 XE54 by Pollock Observatory of near-Earth asteroids 2012 XE54 in 2012 (2013) without lightcurve details, but these have been provided on and 2016 VA in 2016 during close approaches. A request and give the rotation period as 0.02780 ± 0.00002 h, superfast rotation period has been determined for 2012 amplitude 0.33 mag derived from 101 points over a period of 30 XE54 and H-G magnitude system coefficients have been minutes for epoch 2012 Dec 10.2 UT at phase angle 19.5°, estimated for 2016 VA. -

The Minor Planet Bulletin 40 (2013) 125 CS3 Observations on Jan 13 and 14 Were Made with a 0.35-M Schmidt-Cassegrain and SBIG ST-9XE

THE MINOR PLANET BULLETIN OF THE MINOR PLANETS SECTION OF THE BULLETIN ASSOCIATION OF LUNAR AND PLANETARY OBSERVERS VOLUME 40, NUMBER 3, A.D. 2013 JULY-SEPTEMBER 119. SOMETHING OLD, SOMETHINGS NEW: figure shows the lightcurve after removing the rotation of the THREE BINARY DISCOVERIES primary, thus revealing the mutual events and other features due to FROM THE PALMER DIVIDE OBSERVATORY the satellite. The latter often includes an upward bowing between the events, indicating an elongated satellite that is tidally-locked to Brian D. Warner its orbital period. Palmer Divide Observatory 17995 Bakers Farm Rd., Colorado Springs, CO 80908 4383 Suruga. Observations of 4383 Suruga were made from 2013 [email protected] Feb 2-13. Initial observations were made with a 0.35-m Schmidt- Cassegrain and Finger Lakes FLI-1001E CCD camera. When (Received: 10 March) indications of a satellite were seen in those first data sets, the target was moved to a 0.5-m Ritchey-Chretien with FLI-1001E to improve the signal-to-noise ratio. Data on the order of 0.01-0.02 Analysis of new CCD photometric observations in early mag are usually required for reliable detections of mutual events 2013 of the Vestoid asteroid 4383 Suruga and Hungaria (occultations and/or eclipses) caused by a satellite. asteroid (53432) 1999 UT55 showed that the two are binary systems. A review of data from 2005 for the The results of the analysis are shown in Figures 1-3. The period of Hungaria asteroid 4440 Tchantches indicates that the the primary is 3.4068 ± 0.0003 h with an amplitude of 0.14 ± 0.01 original analysis probably overlooked a satellite. -

The Handbook British Astronomical Association

THE HANDBOOK OF THE BRITISH ASTRONOMICAL ASSOCIATION 2008 2007 OCTOBER ISSN 0068-130-X CONTENTS CALENDAR 2008 ............................................................. 2 PREFACE. ................................................................ 3 SKY DIARY FOR 2008 ..................................................... .... 4 VISIBILITYOFPLANETS...................................................... 5 RISING AND SETTING OF THE PLANETS IN LATITUDES 52°N AND 35°S . 6–7 ECLIPSES. ......... ......................................................... 8–12 TIME.................................................................. ..... 13–14 RADIOTIMESIGNALS........................................................ 15 EARTHANDSUN............................................. ................ 16–18 MOON...................................................................... 19 SUN’SSELENOGRAPHIC COLONGITUDE . ................... 20 MOONRISE AND MOONSET ................................................... 21–23 LUNAROCCULTATIONS................................. ..................... 24–32 GRAZINGLUNAROCCULTATIONS............................................. 33–34 PLANETS –EXPLANATIONOFTABLES........................... .............. 35 APPEARANCEOFPLANETS................................................... 36 MERCURY............................................. ...................... 37–38 VENUS. ..................................................................... 39 MARS........................... ............................................ 40–41 MINORPLANETS............................................................ -

The Minor Planet Bulletin (Warner Et Al

THE MINOR PLANET BULLETIN OF THE MINOR PLANETS SECTION OF THE BULLETIN ASSOCIATION OF LUNAR AND PLANETARY OBSERVERS VOLUME 39, NUMBER 3, A.D. 2012 JULY-SEPTEMBER 99. ROTATION PERIOD DETERMINATION FOR 203 others, were also allowed. The only way to fill the large gap in POMPEJA – ANOTHER TRIUMPH OF GLOBAL phase coverage at a single observatory for an Earth commensurate COLLABORATION object is to obtain data from other observatories widely spaced in longitude. Andrea Ferrero in Italy and Hiromi and Hiroko Frederick Pilcher Hamanowa in Japan obtained at the first author's request the 4438 Organ Mesa Loop additional observations required to enable full phase coverage. A Las Cruces, NM 88011 USA total of 14 sessions 2011 Nov. 10 - 2012 Jan. 25 showed a 24.052 [email protected] ± 0.001 hour period, amplitude 0.10 ± 0.01 magnitude and unsymmetric bimodal lightcurve. A lightcurve phased to twice this Andrea Ferrero period showed two halves which were within observational error Bigmuskie Observatory (B88) the same as each other and as the 24.052 hour lightcurve. An via Italo Aresca 12, 14047 Mombercelli, Asti, ITALY irregularly shaped asteroid which was invariant over a 180 degree rotation would be required to produce the 48.1 hour lightcurve. Hiromi Hamanowa, Hiroko Hamanowa The probability of such a symmetric shape for an otherwise Hamanowa Astronomical Observatory irregular real asteroid is so small that it may be safely rejected. 4-34 Hikarigaoka Nukazawa Motomiya Fukushima JAPAN Hence we claim that the 24.052 hour period is the correct one. To make the lightcurve more legible the large number of data points (Received: 30 January) have been binned in sets of three points with a maximum of five Early observations by the first author yielded a rotation minutes between points. -

2014 BAA Handbook 2014 Asteroids 47 ASTEROID OCCULTATIONS Minor Planet Diam Max

THE HANDBOOK OF THE BRITISH ASTRONOMICAL ASSOCIATION 2014 2013 October ISSN 0068-130-X CONTENTS CALENDAR 2014 . 2 PREFACE . 3 HIGHLIGHTS FOR 2014 . 4 SKY DIARY . .. 5 VISIBILITY OF PLANETS . 6 RISING AND SETTING OF THE PLANETS IN LATITUDES 52°N AND 35°S . 7-8 ECLIPSES . 9-13 TIME . 14-15 EARTH AND SUN . 16-18 MOON . 19 SUN’S SELENOGRAPHIC COLONGITUDE . 20 MOONRISE AND MOONSET . 21-25 LUNAR OCCULTATIONS . 26-32 GRAZING LUNAR OCCULTATIONS . 33-34 APPEARANCE OF PLANETS . 35 MERCURY . 36-37 VENUS . 38 MARS . 39-40 ASTEROIDS . 41-53 JUPITER . 54-57 SATELLITES OF JUPITER . 58-62 JUPITER ECLIPSES, OCCULTATIONS AND TRANSITS . 63-72 SATURN . 73-76 SATELLITES OF SATURN . 77-80 URANUS . 81 NEPTUNE . 82 TRANS-NEPTUNIAN & SCATTERED DISK OBJECTS . 83 DWARF PLANETS . 84-87 COMETS . 88-94 METEOR DIARY . 95-97 VARIABLE STARS . 98-103 RZ Cassiopeiae; Algol; λ Tauri; Mira Stars; X Ophiuchi EPHEMERIDES OF DOUBLE STARS . 104-105 BRIGHT STARS . 106 ACTIVE GALAXIES . 107 PLANETS – EXPLANATION OF TABLES . 108 ELEMENTS OF PLANETARY ORBITS . 109 ASTRONOMICAL AND PHYSICAL CONSTANTS . 110-111 INTERNET RESOURCES . 112-113 GREEK ALPHABET . 113 CERES - VESTA APPULSE . 114 ERRATA . 114 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS . 115 Front Cover: C/2011 L4 PanSTARRS approaching the Andromeda Galaxy (M31) on 1st April 2013. It is seen here as it faded from its perihelion naked-eye apparition (Magnitude +2) in March 2013 but its dust trail is nonetheless dramatic and equals the angular size of M31. Its visible coma was estimated at a diameter of 120,000 km. 2011 L4 is a non- periodic comet discovered in June 2011 and may have taken millions of years to reach perihelion from the Oort Cloud. -

The Minor Planet Bulletin

THE MINOR PLANET BULLETIN OF THE MINOR PLANETS SECTION OF THE BULLETIN ASSOCIATION OF LUNAR AND PLANETARY OBSERVERS VOLUME 35, NUMBER 1, A.D. 2008 JANUARY-MARCH 1. ASTEROID LIGHTCURVE ANALYSIS AT THE OAKLEY a V filter at a scale pixel of 2.32 arcseconds per pixel. On one OBSERVATORY – MAY 2007 night, an additional 14-inch Celestron telescope with an Apogee AP-8p camera, operating unfiltered at a pixel scale of 2.00 Scot Hawkins, Richard Ditteon arcseconds per pixel, was used. Four-minute exposures were used Rose-Hulman Institute of Technology CM 171 for most of the data frames. Master flat and dark frames were 5500 Wabash Avenue generated in MaxImDL, and then used in CCDSoft to calibrate the Terre Haute, IN 47803 images. The magnitudes were measured using MPO Canopus. Due [email protected] to the long exposures, the star subtraction option on MPO Canopus was often necessary. (Received: 15 June Revised: 14 October) Asteroids were selected based on their position in the sky one hour after sunset. Priority was given to asteroids without previously Photometric data for 16 asteroids were obtained at the published lightcurves, but asteroids with well-known periods were Oakley Observatory May 19-22, 2007: 205 Martha, 313 also targeted with the hope that the new data would help with Chaldaea, 314 Rosalia, 458 Hercynia, 479 Caprera, 489 shape modeling and determining pole orientation. Comacina, 1384 Kniertje, 1428 Mombasa, 1558 Jarnefelt, 1910 Mikhailov, 2425 Shenzhen, 3165 To our knowledge, these are the first reported rotational periods Mikawa, 5560 Amytis, (5854) 1992 UP, and (15317) for the following asteroids: 1558 Jarnefelt, 1910 Mikhailov, 2425 1993 HW 1. -

Dissecting the Milky Way with Spectroscopic Studies” Can Be

UNIVERSITY OF CAMBRIDGE INSTITUTE OF ASTRONOMY A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE UNIVERSITY OF CAMBRIDGE FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY DISSECTING THE MILKY WAY WITH SPECTROSCOPIC STUDIES KEITH AUSTIN HAWKINS KINGS COLLEGE Submitted to the Board of Graduate Studies August 14, 2016 UNDER THE SUPERVISION OF PROF.GERRY GILMORE &DR.PAULA JOFRE´ “But in the heavens we discover by their light, and by their light alone, stars so distant from each other that no material thing can ever have passed from one to another; and yet this light, which is to us the sole evidence of the existence of these distant worlds, tells us also that each of them is built up of molecules of the same kinds as those which we find on earth.” – James Clerk Maxwell, Molecules, 1873 i ii DECLARATION OF ORIGINALITY I, Keith Austin Hawkins, declare that this Thesis entitled ‘Dissecting the Milky Way with Spec- troscopic Studies’, I confirm that this work was done wholly while in candidature for a research degree at this University, and that this thesis has not previously been submitted for a degree or any other qualification at this University or any other institution. This thesis is the result of my own research and contains nothing resulting from collaboration, except where explicitly noted. The length of this thesis does not exceed the stated limit of the Degree Committee of Physics and Chemistry of 60,000 words.The parts of this Thesis based on published work are as follows: Chapter 2 • “On the ages of the α-rich and α-poor populations in the Galactic halo’ Hawkins, K., Jofre,´ P., Gilmore, G., Masseron, T, 2014, MNRAS, 445, 2575 Chapter 3 • ‘Characterizing the high-velocity stars of RAVE: the discovery of a metal-rich halo star born in the Galactic disc’ Hawkins, K., Kordopatis, G., Gilmore, G., Masseron, T., Wyse, R.