Strategies for Teaching the Millennial Generation in Law School

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bruce Tulgan Is Internationally Recognized As the Leading Expert on Young People in the Workplace and One of the Leading Experts on Leadership and Management

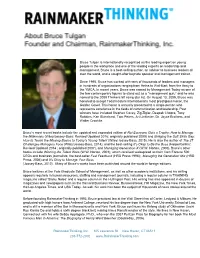

Bruce Tulgan is internationally recognized as the leading expert on young people in the workplace and one of the leading experts on leadership and management. Bruce is a best-selling author, an adviser to business leaders all over the world, and a sought-after keynote speaker and management trainer. Since 1995, Bruce has worked with tens of thousands of leaders and managers in hundreds of organizations ranging from Aetna to Wal-Mart; from the Army to the YMCA. In recent years, Bruce was named by Management Today as one of the few contemporary figures to stand out as a “management guru” and he was named to the 2009 Thinkers 50 rising star list. On August 13, 2009, Bruce was honored to accept Toastmasters International’s most prestigious honor, the Golden Gavel. This honor is annually presented to a single person who represents excellence in the fields of communication and leadership. Past winners have included Stephen Covey, Zig Ziglar, Deepak Chopra, Tony Robbins, Ken Blanchard, Tom Peters, Art Linkletter, Dr. Joyce Brothers, and Walter Cronkite. Bruce’s most recent books include the updated and expanded edition of Not Everyone Gets a Trophy: How to Manage the Millennials (Wiley/Jossey-Bass: Revised Updated 2016; originally published 2009) and Bridging the Soft Skills Gap: How to Teach the Missing Basics to Today’s Young Talent (Wiley/Jossey-Bass, 2015). He is also the author of The 27 Challenges Managers Face (Wiley/Jossey-Bass, 2014), and the best-selling It's Okay to Be the Boss (HarperCollins: Revised Updated 2014 ; originally published 2007), and Managing Generation X (W.W. -

CONFERENCE 2016 RICHMOND MARRIOTT 500 EAST BROAD STREET RICHMOND, VA the 2015 Plutarch Award

BIOGRAPHERS INTERNATIONAL SEVENTH JUNE 35 ANNUAL CONFERENCE 2016 RICHMOND MARRIOTT 500 EAST BROAD STREET RICHMOND, VA The 2015 Plutarch Award Biographers International Organization is proud to present the Plutarch Award for the best biography of 2015, as chosen by you. Congratulations to the ten nominees for the Best Biography of 2015: The 2016 BIO Award Recipient: Claire Tomalin Claire Tomalin, née Delavenay, was born in London in 1933 to a French father and English mother, studied at Cambridge, and worked in pub- lishing and journalism, becoming literary editor of the New Statesman, then of the (British) Sunday Times, while bringing up her children. In 1974, she published The Life and Death of Mary Wollstonecraft, which won the Whitbread First Book Prize. Since then she has written Shelley and His World, 1980; Katherine Mansfield: A Secret Life, 1987; The Invisible Woman: The Story of Nelly Ternan and Charles Dickens, 1991 (which won the NCR, Hawthornden, and James Tait Black prizes, and is now a film);Mrs. Jordan’s Profession, 1994; Jane Austen: A Life, 1997; Samuel Pepys: The Unequalled Self, 2002 (winner of the Whitbread Biography and Book of the Year prizes, Pepys Society Prize, and Rose Crawshay Prize from the Royal Academy). Thomas Hardy: The Time-Torn Man, 2006, and Charles Dickens: A Life, 2011, followed. She has honorary doctorates from Cambridge and many other universities, has served on the Committee of the London Library, is a trustee of the National Portrait Gallery, and is a vice-president of the Royal Literary Fund, the Royal Society of Literature, and English PEN. -

The Great Generational Shift UPDATE 2017 by Bruce Tulgan by Bruce Tulgan

The Great Generational Shift UPDATE 2017 By Bruce Tulgan By Bruce Tulgan Since 1993, we have been tracking the “Great Generational Shift” underway in the workforce and we remain committed to updating our research every year in this white paper. To date, our primary research has included hundreds of thousands of participants from more than 400 organizations, as well as our ongoing review of internal survey data from our clients reflecting millions of respondents. In this 2017 update, we provide adjustments based on our latest data from tracking this powerful demographic transformation. This is the generational shift that demographers and workforce planners have been anticipating for decades. Now it’s actually happening. As the Baby Boomers’ slow but steady exodus from the workforce continues, the Second Wave Millennials continue entering the workforce in droves. This radical shift in numbers is accompanied by a profound transformation in the norms, values, attitudes, expectations and behaviors of the emerging post-Boomer workforce. What follows: 1. The Numbers Problem: Workforce 2017 (and 2020 is just around the corner). 2. The Forces Driving Change: No Ordinary Generation Gap. 3. The Workforce of the Future Is Arriving: Welcome to the Workplace of the Future. 4. Human Capital Management 2017: What Does the Generational Shift Mean for Employers? 5. Employee Mindset 2017: Spotlight on the Second Wave Millennials. 6. Leadership 2017: What Does the Generational Shift Mean for Leaders, Managers, and Supervisors? 1 Copyright, RainmakerThinking, Inc., 2017, All Rights Reserved 1. The Numbers Problem: Workforce 2017 (and 2020 is just around the corner). Based on our model, there are six different generations still working side by side in 2017, but just barely: Note: Demographers differ about the exact parameters of each generation. -

WEB Amherst Sp18.Pdf

ALSO INSIDE Winter–Spring How Catherine 2018 Newman ’90 wrote her way out of a certain kind of stuckness in her novel, and Amherst in her life. HIS BLACK HISTORY The unfinished story of Harold Wade Jr. ’68 XXIN THIS ISSUE: WINTER–SPRING 2018XX 20 30 36 His Black History Start Them Up In Them, We See Our Heartbeat THE STORY OF HAROLD YOUNG, AMHERST- WADE JR. ’68, AUTHOR OF EDUCATED FOR JULI BERWALD ’89, BLACK MEN OF AMHERST ENTREPRENEURS ARE JELLYFISH ARE A SOURCE OF AND NAMESAKE OF FINDING AND CREATING WONDER—AND A REMINDER AN ENDURING OPPORTUNITIES IN THE OF OUR ECOLOGICAL FELLOWSHIP PROGRAM RAPIDLY CHANGING RESPONSIBILITIES. BY KATHARINE CHINESE ECONOMY. INTERVIEW BY WHITTEMORE BY ANJIE ZHENG ’10 MARGARET STOHL ’89 42 Art For Everyone HOW 10 STUDENTS AND DOZENS OF VOTERS CHOSE THREE NEW WORKS FOR THE MEAD ART MUSEUM’S PERMANENT COLLECTION BY MARY ELIZABETH STRUNK Attorney, activist and author Junius Williams ’65 was the second Amherst alum to hold the fellowship named for Harold Wade Jr. ’68. Photograph by BETH PERKINS 2 “We aim to change the First Words reigning paradigm from Catherine Newman ’90 writes what she knows—and what she doesn’t. one of exploiting the 4 Amazon for its resources Voices to taking care of it.” Winning Olympic bronze, leaving Amherst to serve in Vietnam, using an X-ray generator and other Foster “Butch” Brown ’73, about his collaborative reminiscences from readers environmental work in the rainforest. PAGE 18 6 College Row XX ONLINE: AMHERST.EDU/MAGAZINE XX Support for fi rst-generation students, the physics of a Slinky, migration to News Video & Audio Montana and more Poet and activist Sonia Sanchez, In its interdisciplinary exploration 14 the fi rst African-American of the Trump Administration, an The Big Picture woman to serve on the Amherst Amherst course taught by Ilan A contest-winning photo faculty, returned to campus to Stavans held a Trump Point/ from snow-covered Kyoto give the keynote address at the Counterpoint Series featuring Dr. -

Bruce Tulgan Is Internationally Recognized As the Leading Expert on Young People in the Workplace and One of the Leading Experts on Leadership and Management

Bruce Tulgan is internationally recognized as the leading expert on young people in the workplace and one of the leading experts on leadership and management. Bruce is a best-selling author, an adviser to business leaders all over the world, and a sought-after keynote speaker and management trainer. Since 1995, Bruce has worked with tens of thousands of leaders and managers in hundreds of organizations ranging from Aetna to Wal-Mart; from the Army to the YMCA. In recent years, Bruce was named by Management Today as one of the few contemporary figures to stand out as a “management guru” and he was named to the 2009 Thinkers 50 rising star list. On August 13, 2009, Bruce was honored to accept Toastmasters International’s most prestigious honor, the Golden Gavel. This honor is annually presented to a single person who represents excellence in the fields of communication and leadership. Past winners have included Stephen Covey, Zig Ziglar, Deepak Chopra, Tony Robbins, Ken Blanchard, Tom Peters, Art Linkletter, Dr. Joyce Brothers, and Walter Cronkite. Bruce’s most recent books include the updated and expanded edition of Not Everyone Gets a Trophy: How to Manage the Millennials (Wiley/Jossey-Bass: Revised Updated 2016; originally published 2009) and Bridging the Soft Skills Gap: How to Teach the Missing Basics to Today’s Young Talent (Wiley/Jossey-Bass, 2015). He is also the author of The 27 Challenges Managers Face (Wiley/Jossey-Bass, 2014), and the best-selling It's Okay to Be the Boss (HarperCollins: Revised Updated 2014 ; originally published 2007), and Managing Generation X (W.W. -

Exvangelical: Why Millennials and Generation Z Are Leaving the Constraints of White Evangelicalism

Digital Commons @ George Fox University Doctor of Ministry Theses and Dissertations 2-2020 Exvangelical: Why Millennials and Generation Z are Leaving the Constraints of White Evangelicalism Colleen Batchelder Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.georgefox.edu/dmin Part of the Christianity Commons GEORGE FOX UNIVERSITY EXVANGELICAL: WHY MILLENNIALS AND GENERATION Z ARE LEAVING THE CONSTRAINTS OF WHITE EVANGELICALISM A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF PORTLAND SEMINARY IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF MINISTRY BY COLLEEN BATCHELDER PORTLAND, OREGON FEBRUARY 2020 Portland Seminary George Fox University Portland, Oregon CERTIFICATE OF APPROVAL ________________________________ DMin Dissertation ________________________________ This is to certify that the DMin Dissertation of Colleen Batchelder has been approved by the Dissertation Committee on February 20, 2020 for the degree of Doctor of Ministry in Leadership and Global Perspectives Dissertation Committee: Primary Advisor: Karen Tremper, PhD Secondary Advisor: Randy Woodley, PhD Lead Mentor: Jason Clark, PhD, DMin Copyright © 2020 by Colleen Batchelder All rights reserved ii TABLE OF CONTENTS GLOSSARY .................................................................................................................. vi ABSTRACT .................................................................................................................... x CHAPTER 1: GENERATIONAL DISSONANCE AND DISTINCTIVES WITHIN THE CHURCH ....................................................................................................................... -

Bruce Tulgan Founder/Chairman, Rainmaker Thinking, Inc. Bruce

Bruce Tulgan Founder/Chairman, Rainmaker Thinking, Inc. Bruce Tulgan is internationally recognized as the leading expert on young people in the workplace and one of the leading experts on leadership and management. Bruce is a best-selling author, an adviser to business leaders all over the world, and a sought-after keynote speaker and management trainer. Since 1995, Bruce has worked with tens of thousands of leaders and managers in hundreds of organizations ranging from Aetna to Wal-Mart; from the Army to the YMCA. He has been called “the new Tom Peters” by many who have seen him speak. In recent years, Bruce was named by Management Today as one of the few contemporary figures to stand out as a “management guru” and he was named to the 2009 Thinkers 50 rising star list (the Thinkers 50 is the definitive global ranking of the world’s top 50 business thinkers). And on August 13, 2009, Bruce was honored to accept Toastmasters International’s most prestigious honor, the Golden Gavel. This honor is annually presented to a single person who represents excellence in the fields of communication and leadership. Past winners have included Marcus Buckingham, Stephen Covey, Zig Ziglar, Deepak Chopra, Tony Robbins, Ken Blanchard, Tom Peters, Art Linkletter, Dr. Joyce Brothers, and Walter Cronkite. Bruce’s newest book is It’s Okay to Manage Your Boss (Jossey-Bass, September 14, 2010). He is also the author of the recent best-seller It’s Okay To Be The Boss (HarperCollins, 2007) and the classic Managing Generation X (W.W. Norton, 2000; first published in 1995). -

Bruce Tulgan

Bruce Tulgan Management Consultant, RainmakerThinking, Inc. Bruce Tulgan is internationally recognized as the leading expert on young people in the workplace and one of the leading experts on leadership and management. Bruce is a best-selling author, an adviser to business leaders all over the world, and a sought-after keynote speaker and management trainer. Since 1995, Bruce has worked with tens of thousands of leaders and managers in hundreds of organizations ranging from Aetna to Wal-Mart; from the Army to the YMCA. In recent years, Bruce was named by Management Today as one of the few contemporary figures to stand out as a “management guru” and he was named to the 2009 Thinkers 50 rising star list. On August 13, 2009, Bruce was honored to accept Toastmasters International’s most prestigious honor, the Golden Gavel. This honor is annually presented to a single person who represents excellence in the fields of communication and leadership. Before founding RainmakerThinking in 1993, Bruce practiced law at the Wall Street firm of Carter, Ledyard & Milburn. He graduated with high honors from Amherst College, received his law degree from the New York University School of Law, and is still a member of the Bar in Massachusetts and New York. Bruce continues his lifelong study of Okinawan Uechi Ryu Karate Do and holds a fifth degree black belt. He lives in New Haven, Connecticut with his wife Debby Applegate, Ph.D., who won the 2007 Pulitzer Prize for Biography for her book The Most Famous Man in America: The Biography of Henry Ward Beecher (Doubleday, 2006). -

About the Author: Bruce Tulgan

About the Author: Bruce Tulgan The Art of Being Indispensable at Work: Win Influence, Beat Overcommitment, and Get the Right Things Done (Harvard Business Review Press, 2020) One-sentence bio: Bruce Tulgan is the best-selling author of numerous books including It’s Okay to Be the Boss and the founder and CEO of RainmakerThinking, a management research, training, and consulting firm. Medium bio: Bruce Tulgan is the best-selling author of It’s Okay to Be the Boss and the CEO of RainmakerThinking, the management research, consulting and training firm he founded in 1993. All of his work is based on 27 years of intensive workplace interviews and has been featured in thousands of news stories around the world. Bruce’s newest book, The Art of Being Indispensable at Work, is available July 21 from Harvard Business Review Press. You can follow Bruce on Twitter @BruceTulgan or visit his website at rainmakerthinking.com. Long bio: Bruce Tulgan is internationally recognized as one of the leading experts on leadership and management. He is a best-selling author, an adviser to business leaders all over the world, and a sought-after keynote speaker and management trainer. Since founding RainmakerThinking, the research, training and consulting firm, in 1993, Bruce has worked with tens of thousands of leaders and managers in hundreds of organizations ranging from Aetna to Wal-Mart; from the U.S. Army to the YMCA. Bruce’s newest book, The Art of Being Indispensable at Work, is available July 21 from Harvard Business Review Press. His other books include the best-selling It’s Okay to Be the Boss, The 27 Challenges Managers Face, and Not Everyone Gets a Trophy. -

OACCAC Proudly Presents a Session with Bruce Tulgan March 19 & 20

OACCAC Proudly Presents A Session with Bruce Tulgan March 19 & 20, 2007 March 19 1:00 p.m. - 5:00 p.m. March 20 9:00 a.m. - 5:00 p.m. Harper Collins is releasing Bruce Tulgan’s New Book Bruce Tulgan will be at: Toronto Marriott Downtown Eaton Centre 525 Bay Street, Toronto Ontario M5G 2L2 March 19 & 20, 2007 Registration Fee: $685 + GST $726.10 OACCAC has negotiated a Conference Room Rate of $149. per person + Applicable Taxes and Fees The First 50 Registrants will receive a signed copy of his NEW BOOK! e-Registration can be accessed at https://secure.e-registernow.com/cgi-bin/mkpayment.cgi?MID=788&state=step2direct&event=3126220994254 IT’S OKAY TO BE THE BOSS: The Step-by-Step Guide to Becoming the Manager Your Employees Need By Bruce Tulgan (March 2007, HarperCollins) Book Summary Do you feel you don’t have enough time to manage your people? Do you avoid interacting with some employees because you hate the dreaded confrontations that often follow? Do you have some great employees you really cannot afford to lose? Do you secretly wish you could be more in control but don’t know where to start? Managing people is harder and more high-pressure today than ever before: There’s no room for down time, waste, or inefficiency. You have to do more with less. And employees have become high maintenance. Not only are they more likely to disagree openly and push back, but they also won’t work hard for vague promises of long-term rewards. -

Amherst Today

ALSO INSIDE FALL The 1896 alum 2017 who unearthed our mammoth skeleton is still frustrating and surprising scientists Amherst today. As the College’s first Army ROTC FUTURE student in two decades, Rebecca Segal ’18 is part of the long, rich, VETERAN complex story of Amherst and the military. XXIN THIS ISSUE: FALL 2017XX 20 28 36 Veterans’ Loomis “The Splendor of Days Illuminated Mere Being” FROM THE CIVIL WAR TO AN THE PROFESSOR WHO THE COLLEGE REMEMBERS “ACADEMIC BOOT CAMP” UNEARTHED AMHERST’S ACCLAIMED POET AND THIS SUMMER, AMHERST’S MAMMOTH SKELETON IN LECTURER RICHARD HISTORY OF TEACHING 1923 IS STILL FRUSTRATING WILBUR ’42, WHO DIED MEMBERS OF THE MILITARY AND SURPRISING THIS FALL. BY KATHARINE SCIENTISTS TODAY. BY KATHARINE WHITTEMORE BY GEOFFREY GILLER ’10 WHITTEMORE Inside the College’s Beneski Museum, a local scientist realized that this Tyrannosaurid jaw is different from any other he’s seen. (And he has seen quite a few.) Page 28 Photograph by GEOFFREY GILLER ’10 2 “We take pleasure in First Words A career in pediatric cardiology seeing the impossible inspires a young adult novel. appear possible, and the 4 invisible appear visible.” Voices Readers consider such far-reaching Historian Thomas W. Laqueur, invited to Amherst as issues as China’s one-child policy, a Phi Beta Kappa Visiting Scholar, during his October nuclear war and the search for lecture on how and why the living care for and extraterrestrial life. remember the dead. PAGE 12 6 College Row Support after Hurricane Maria, XX ONLINE: AMHERST.EDU/MAGAZINE XX researching bodily bacteria, Amherst’s “single finest graduate” News Video & Audio and more Jeffrey C. -

The Art of Being Indispensable at Work Win Influence, Beat Overcommitment, and Get the Right Things Done

MEDIA KIT THE ART OF BEING INDISPENSABLE AT WORK WIN INFLUENCE, BEAT OVERCOMMITMENT, AND GET THE RIGHT THINGS DONE BY BRUCE TULGAN HARVARD BUSINESS REVIEW PRESS BEING INDISPENSABLE AT WORK BRUCE TULGAN Bestselling author, It’s Okay to Be the Boss HARVARD BUSINESS REVIEW PRESS In today’s workplace, everybody is dealing with so many people–up, down, sideways, and diagonal. In this game-changing book, talent guru and bestselling author Bruce Tulgan shows how Go-to People not only behave differently, but also think differently, building up their influence with others by doing the right things at the right times for the right reasons regardless of whether they have any formal designation of authority. Endorsements “For anybody at any level in any organization who wants to be that indispensable go to person, read this book.” --Ray Blanchette, President & CEO, TGI Friday’s “Do you want to be a better leader, better performer, or #1 in your peer group? If so, read this book. Both of my sons are young military officers, and I’m sending them a copy.” --Greg Lengyel, Major General, USAF Financial Times: FT business books: July edition (retired), Deputy Commanding General U.S. Publishers Weekly: Humane Resources: Joint Special Operations Command (2016-2018), Business Books 2020 Vice President Sandoval Title: The Art of Being Indispensable at Work: “This could be the most practical and immediately usable book I have ever read. Win Influence, Beat Overcommitment, and Bruce just gave you the ultimate roadmap.” Get the Right Things Done --Eric Hutcherson,